Independent Spirit: Milestone's 'Magic Box' Restores Shirley Clarke to the Avant-Garde Pantheon

Once, when asked about the contributions of the filmmaker Shirley Clarke to the evolution of film as an art form, my mind drew a blank. I made a connection after being reminded that she had directed the mesmerizing cinema vérité Portrait of Jason, an interview with Jason Holliday, a gay, black, male hustler and performer extraordinaire, shot over 12 hours on December 3, 1966. This notable film, edited down to an hour and 45 minutes, had been impossible to see until Dennis Doros and Amy Heller, the founders of the independent distribution company Milestone Films, released the digitized restored version in 2012. It was part of their eight-year commitment to preserve and distribute the films of Shirley Clarke.

Milestone had previously restored and released two other Clarke features: The Connection (1961) and Ornette: Made in America (1985). When released, these films were critically praised for their risk-taking improvisations with the medium. But they were controversial. The Connection, in particular, was targeted, deemed obscene and banned in New York State.

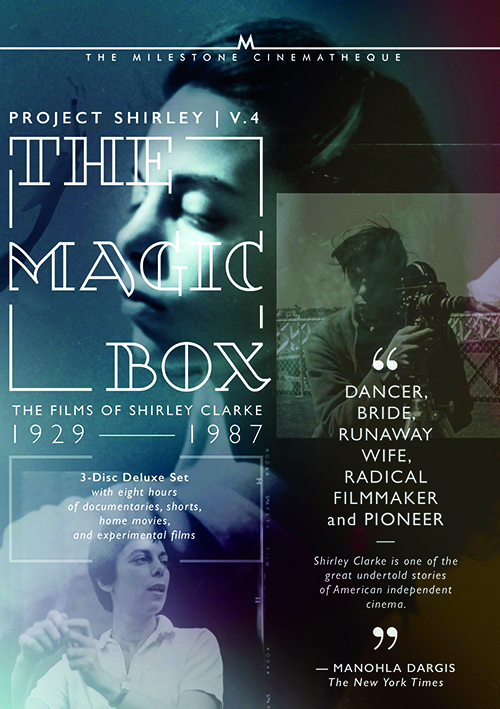

The Magic Box: The Films of Shirley Clarke 1929-1987: Project Shirley Volume 4.

3 Disc Set

The Milestone Cinematheque

Now, with the release of The Magic Box: The Films of Shirley Clarke 1929-1987, Milestone has gifted us with all the evidence any film historian would need in order to include Clarke alongside the pantheon of innovators—in the same league as John Cassavetes on the auteur side or DA Pennebaker in the documentary genre.

Film preservation, restoration and access is an arduous and complex process, as anyone who has attempted this work for even a single film knows. It is not for the impatient or faint of heart. If it were not for the dedication of people like Doros and Heller at Milestone Films and also the ongoing work of The Criterion Collection, much of our film history would have been lost to the onslaught of time and vinegar syndrome.

In the small brochure that accompanies The Magic Box, we are informed of "hundreds of colleagues and archivists," all of whom contributed to the realization of the project: the Wisconsin Center for Film and Television, the Museum of Modern Art Film Department, the UCLA Film & Television Archive, the Academy Film Archive, the Anthology Film Archive, Colorlab, FotoKem, DA Pennebaker and his son Frazer Pennebaker. But perhaps the most important supporter was Clarke's daughter Wendy, who helped sift through the personal letters, diaries, notebooks, screenplays, doodles and family photo albums that helped contextualize one-of-a-kind 16mm prints that had not been screened publicly, or at all, since the 1950s.

Shirley Clarke was born Shirley Brimberg in New York City in 1919 to a wealthy family, and she was raised in an atmosphere of privilege. We get to see the intimate trappings of her early life in the seven family home movies included on Disc 3 of the box set. They show young Shirley during summers at their New Jersey home, her wedding to Bert Clarke, their honeymoon, her pregnancy, and the first image of her holding the Bolex 16mm camera they received as a wedding present. It was the same camera later used to launch her career in film.

It was not film, but dance that initially captured Clarke's creative instincts. An article from the Dance Film Association states, "Shirley Clarke is a dancer's dancer and a filmmaker's filmmaker, the rare bird that can not only successfully transition from one challenging art to another, but see the line between the two as indistinct, allowing one to freely inform the other." She studied dance at college and trained professionally under the Martha Graham and Hannah Holm Technique of Modern Dance. Disc 2, simply titled Dance, shows the passion and energy Clarke brought to her craft in a series of still photos that show her dancing in the 1930s. Through collaborations with accomplished dancers Beatrice Seckler and Anna Sokolow, Clarke shifted position from in front of to behind the camera. Fear Flight (1950), a 10-minute short with Seckler, was her first attempt at filmmaking and is included here. Her first "official" film, Dance in the Sun (1953), starring Daniel Nagrin, celebrates the body of the solo dancer as he embraces the joy of being alive on the beach on a beautiful day. In Paris Parks (1954), a delightful experience and one of her most successful shorts, features young children, including her daughter Wendy, who plays with a hoop and stick in the film. There are examples of unfinished work on this disc, such as The Rose and The Players, based on a painting by Pablo Picasso, along with outtakes from In Paris Parks, all of which give a glimpse into Clarke's behind-the-scenes editing and filmmaking process.

Clarke's most experimental work is clustered together on Disc 1. Brussels Loops is the opening film, an hour-long feature made up of three-minute silent vignettes commissioned for the American Pavilion at the 1957 Brussels World Fair. Surprisingly, most of the camerawork was done by DA Pennebaker, while Clarke was responsible for editing. She said she cut them as jazz pieces, which certainly comes across in the visual rhythm of the piece. She went on to work with Pennebaker on other projects and did two video collaborations with playwright Sam Shepard, Tongues and Savage/Love, that featured innovative special effects.

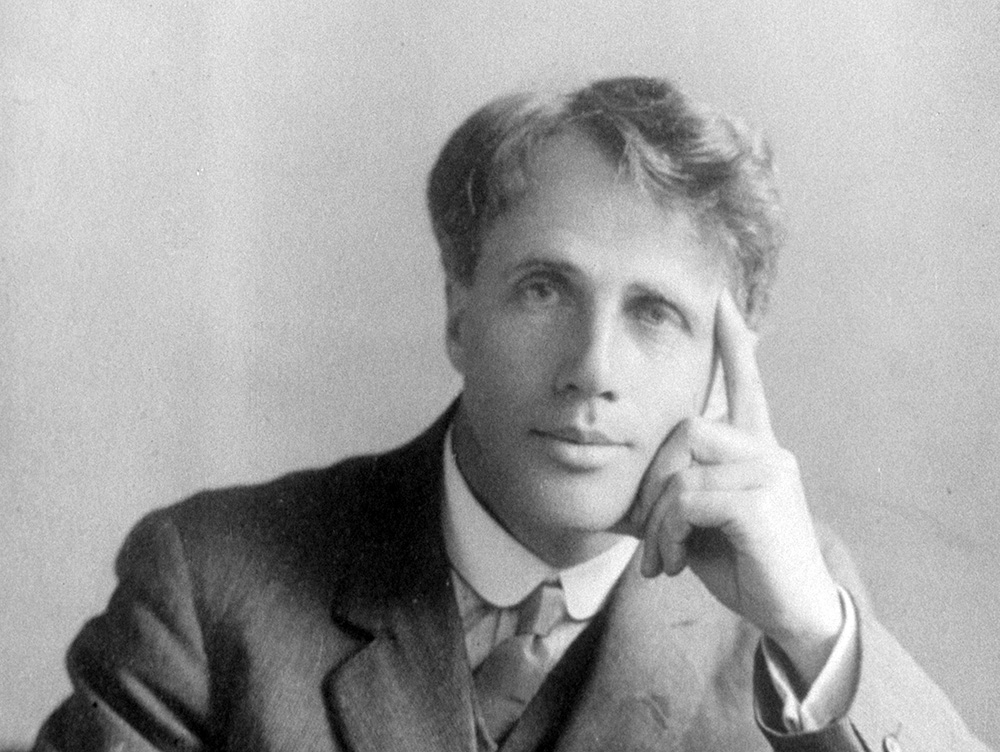

Robert Frost: A Lover's Quarrel with the World won the Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1964. It is perhaps the most accessible film of the collection and is the first film that opens Disc 3. It is in black and white, and was produced at WGBH in Boston. Frost carries the entire film, as it features him reading his work with humor and pathos to a rapt audience. It gave me a whole new appreciation for the poet not only as an artist, but also as a human being. Clarke is credited as the director, and while she attended the Oscars, it was under a cloud of controversy. WGBH had replaced her at some point with the producer Robert Hughes. It is unclear who was responsible for what in the film that was ultimately released. The version included here is the complete version, restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Academy Film Archive. A short television interview broadcast in 1956 at the beginning of Clarke's film career, just as her first dance films were attracting attention, is included near the end of Disc 3. It shows us a determined, self-aware young woman, even as she casually twirls the pack of cigarettes in her hands. She laughs, admitting that the industry "treats her nicely," perhaps because she is a woman in a man's world and they don't quite know what to do with her. A few years later, she was more pointed and direct about her mission in life, as she relates in a 1962 interview: "Right now, I'm revolting against the conventions of movies. Who says a film has to cost a million dollars and be safe and innocuous enough to satisfy every 12-year-old in America?...We're creating a movie equivalent of Off-Broadway, fresh and experimental and personal. The lovely thing is that I'm alive at just the time when I can do this.''

Although Clarke died in 1997 in Boston, her legacy remains in her films, and thanks to the dedication of the folks at Milestone Films along with her daughter Wendy, we can all be reminded just how audacious she was.

Cynthia Close is the former president of Documentary Educational Resources. She currently resides in Burlington, Vermont, where she consults on the business of film and serves on the advisory board of the Vermont International Film Festival.