To school myself in documentary filmmaking after a career in journalism, I gave myself a daily assignment, which I held to faithfully for nearly two years: Every morning before heading to work, I watched a movie. Most were documentaries, but not all. I also watched films that had what I called "journalistic pretensions" and were based on reporting, like The Insider or Argo.

I saw hundreds and hundreds of films. Most of them made strident arguments about their subject matters, for or against. That seemed easy enough—maybe too easy. I found myself drawn to stories where the filmmaker let me be the judge—a much more challenging approach. Of this variety, no film stays with me more than Grizzly Man, Werner Herzog's classic of forensic portraiture.

It would have been tempting to ridicule his doomed subject, Timothy Treadwell, a man who "tried to be a bear," as one interview subject tells us. Instead, Herzog crafts an ingenious tribute to error, and by probing what some might consider madness, he finds a complex exegesis of civilization itself.

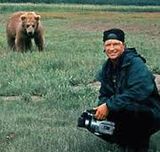

From the first seconds, we know that Treadwell, shooting his own story, is a reckless romantic who takes refuge among Alaska's grizzlies. This is an unwise arrangement for man and bear alike, and we know immediately how it all ends. But for more than half the film, Herzog invites us to appreciate Treadwell's worldview, talents and desires, all of which the director exhumed from the 100-hour archive Treadwell left behind.

"I found that beyond a wildlife film, in his material lay dormant a story of astonishing beauty and depth," Herzog tells us in his Teutonic narration. "I discovered a film of human ecstasies and darkest inner turmoil. As if there was a desire in him to leave the confinements of his humanness and bond with the bears, Treadwell reached out seeking a primordial encounter."

The film handles Treadwell's folly with deep respect, though never without gentle criticism. We know not to try this at home. But what Herzog does magnificently is judge Treadwell on his own terms, as a man who is sure he is doing right.

Eventually, though, we must acknowledge the ferocity of the wild animals. Treadwell addresses the idea early on, but for bravado only. You sense he doesn't believe it when he says, "If I show weakness, if I retreat, I may be hurt, I may be killed. I must hold my own if I am going to stay within this land. For once there is weakness, they will exploit it, they will take me out, they will decapitate me, they will chop me into bits and pieces."

But when Treadwell stumbles on a half-eaten fox pup in a scrubby field, he weeps angrily and curses the world. "I love you and I don't understand," he decries over the tiny corpse. "It's a painful world."

This is the first and only time Herzog corrects his subject. "Here, I differ with Treadwell," he tells us.

Those words are the turning point for both men, and for the film, which begins a steady beat back to Treadwell's harrowing last minutes. But it does not signal a negation of Treadwell; quite the opposite. Herzog sees Treadwell here as the mad artist, a Prince Valiant, a Thoreau even, and tells us, "I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony, but chaos, hostility and murder."

But with those generous few words—"I differ with Treadwell"—he renders his own judgment as a matter of philosophical difference, and lets you and me draw our own conclusions—about Treadwell and Herzog both, and about the world around us, kind or cruel.

David France, an award-winning author and New York magazine contributor, was named IDA's Emerging Documentary Filmmaker for 2012. His Oscar-nominated film about AIDS activism, How to Survive a Plague, received top honors numerous festivals and from New York Film Critics Circle, Gotham, GLAAD, Cinema Eye, Boston Society of Film Critics, Central Ohio Film Critics Association, and the Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association.