Media historians will look back on 2000 as the summer when European and American broadcasting reached the same wavelength. "Voyeur TV" is hurtling through broadcasting markets, breaking viewer records and causing critics everywhere to ponder its greater meaning.

But the US and Europe have arrived at this common ground from very different directions. In the US, reality-based television represents a sharp departure from major network primetime fare of a year ago. The trend is also significant for its reversal in the usual stream of exports of American formats abroad: Big Brother and Survivor, both bought by CBS, constitute the first time a major American commercial network has bought formats from a non-native English speaking country.

But in Europe, Big Brother and its ilk represent the culmination of an increasing dependence on factual programming as a major provider of television entertainment. Nowhere is the breadth and variety of entertaining documentaries more in evidence than in the United Kingdom.

The UK has been the frontrunner in using the documentary format to explore all aspects of "real life" on television, helped along by a public service philosophy that television must inform and educate as well as entertain. As a typical example of how integral factual programming is on primetime schedules, consider the following: On a random Tuesday this summer, as Big Brother gears up for its 11pm nightly wrap up of the day's events, Britain's five networks broadcast 22 programs of various lengths between 8 and 11pm. Thirteen are documentaries.

In the last decade, as US commercial networks have continued to focus on sitcoms and dramas, British broadcasters have increasingly realized that real people can be the source of thought-provoking entertainment. In the mid-90s, UK broadcasting schedules groaned with an explosion of documentary soap-operas, tracking ordinary people going about their daily lives (see November 1999 International Documentary). When watching real people in their natural habitat seemed to get old, programmers came up with a new twist: taking real people and putting them into un-real situations. Tuesday night's offerings included several "constructed" documentaries, including a survival series pitting different professions against each other, and a show which follows want-to-be inventors as they're given a task of improving upon an existing design (in this case a more user-friendly trash can).

Even in this varied landscape, however, Big Brother has caused a sensation among "water cooler" television. Its game show element, where the only housemate not voted out earns a cash prize provides a new twist to the constructed documentary, while the Web site, press releases and exhaustive nightly programming made it hard for the public to ignore.

But while Big Brother has caused a flurry of press in Britain, it's generally not being greeted as revolutionary. Television producer Jeremy Mills says that the success of Big Brother doesn't pose a threat to documentaries on British television, but merely has positioned itself on the low end of the scale: "Big Brother doesn't have any pretensions than to be anything other than entertaining. It's a freak show with much more in keeping with Jerry Springer than genuine documentaries. There's room for both."

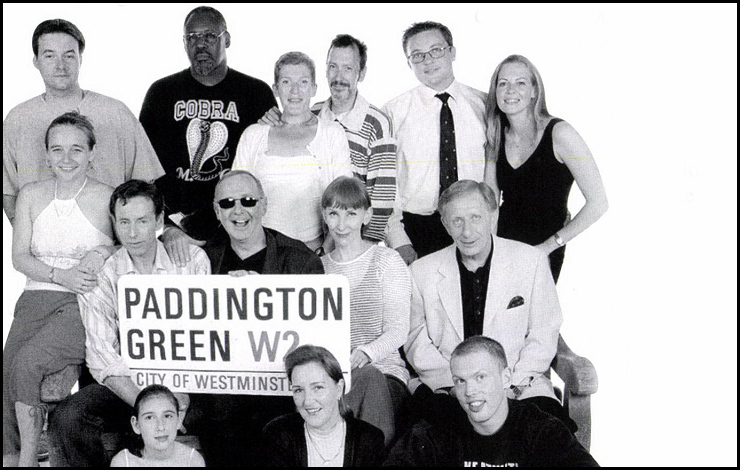

Mills should know: he's one of the most successful documentary makers in British television. His production company Lion TV is responsible for several of Tuesday's primetime documentaries, including the extraordinarily popular Paddington Green series, which follows the many different types of lives being played out in a London square. He produced more than 100 documentaries for the BBC last year alone.

Mills is also the force behind the BBC's high-rating millennium documentary, Castaway 2000. On January 1, the project sent 36 men, women and children to a cold and barren island off the west coast of Scotland to create their own society for an entire year. Their progress, primarily filmed through video diaries made by the castaways themselves, is tracked on the BBC periodically throughout the year.

For years, Mills has concentrated on making factual programs that aim to look at fundamental issues in society in an entertaining way. Despite outward similarities, he says Big Brother is worlds apart from Castaway 2000. "It's a very good and entertaining game show, with roots in other game shows, while Castaway stems from documentaries. It depends where you start your journey. You may come out in similar places but you get there different ways."

Having jumped in at the game show end of the documentary spectrum, US broadcasters are now looking at what else can be learned from the British. Mills has already made a number of reality-based series for A&E, Discovery, and MSNBC, as well as a series for PBS about Boston district attorneys. Castaway began airing on BBC America last month.

After successfully mining the ever-reserved British for program material, Mills is enthusiastic about coming to America: "The States is such a wonderful, rich country. It's a filmmaker's dream."

Carol Nahra (carolnahra@hotmail.com) is an American journalist based in London.