Donald Richie first arrived in Japan over 50 years ago, when he was hired to work as a typist for the Stars and Stripes American military newspaper. Richie informed the newspaper that they were lacking a film critic, and he was quickly appointed to the position. He recalls, “That’s when I first started being interested in Japanalia. I taught myself, through trying to teach members of the Occupation, what noh was, what kabuki was, what the tea ceremony was.”

“I was much more interested in learning about Japanese films,” he continues. “So I would sneak into theaters, and not knowing the language, would try to put together what it was they were showing on the screen. I realized at once that their way of telling stories, their narrational methods, were very, very different.”

Richie left Japan in the late 1940s to return to the United States to pursue a college education. “When I came back in 1953, after graduating from Columbia,” Richie recalls, “I learned Japanese right away and I was able to make more sense of what I was seeing, little by little putting together this large map, which really became my view of the Japanese film.”

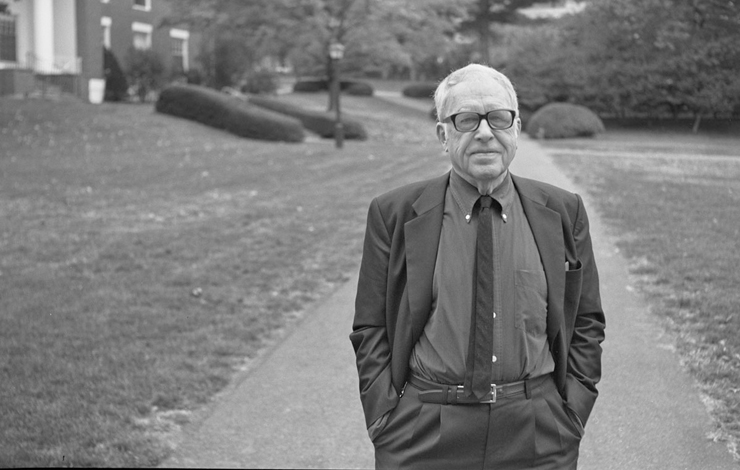

His love affair with Japanese cinema was thus kindled, and in the decades that followed Richie established himself as the West’s foremost expert in Japanese cinema, having helped introduce Western viewers and readers to it through his seminal books on Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu. Returning to the United States to work as curator of film at the Museum of Modern Art from 1968 to 1974, Richie instigated retrospectives on Japanese film. He reached new audiences through his film criticism for The Japan Times and The International Herald Tribune, and through various film festivals that he has helped to curate, including Telluride, Nantes and many others. Richie continues to live in Tokyo, where he mixes and mingles with the freedom and confidence of an insider yet maintains the vantage point of an outsider.

Richie’s own life in Japan was brought to life in the poignant and poetic 1991 documentary, The Inland Sea (Lucille Carra), named after his book of the same name. The documentary examines Richie’s outlook on Japan, his life as an expatriate, and his deep love for a Japan that is quickly succumbing to the pressures of modernization, overdevelopment, and franchising. Of the film, Richie comments, “A person who is living outside of his own culture, outside of his own past, who is living someplace which is absolutely new for him, where they’re not used to him and he’s not used to them, can see better, hear better, listen better, learn more and find out more about his own inland sea.”

Richie’s latest endeavors include the newly-published The Donald Richie Reader (Stone Bridge Press) and the forthcoming One Hundred Years of Japanese Film (published by Kodansha). Richie’s novel Tokyo Nights is currently being adapted into a feature film by Wayne Wang. In a recent interview, Richie shed light on the state of the documentary in Japan, both past and present. “The Japanese film seems to be combined of two styles: representation and presentation,” he affirms. “Representation is simply realism: you represent. There’s nothing standing, presumably standing, between you and the object you’re photographing, the documentary ideal. In Japan, we still have a degree of presentation that I don’t believe any other body of film history can show us. In the cinema, the early days of cinema, before sound, we had men (in Japan) called benchi who came and told you the story, which they would often make up, to tell you what you were going to see, what you were seeing while you were seeing it, and what you had seen, and at the same time gave many an intimation as to how you were to feel about it. So this is presentation.”

This degree of presentation has permeated Japanese film, Richie relates. Even in realist films, such as Kurosawa’s Ikiru, we hear an authoritative voice in the middle of the film, the Japanese voice, at which time the film switches abruptly from representational to presentational.

One of the effects of this extraordinary duality is that documentary had never had much influence in Japan until after World War II. Besides newsreels, the first look that the Japanese had at anything that might be considered a documentary was the German kultur-film of the 1930s. The Japanese adapted the kultur-film model, while documentaries by British and American makers were not screened in Japan until after the war.

“The first Japanese documentary maker of note is, arguably, Hani Susumu,” Richie maintains. “He made very lyrical documentaries, including Children Who Draw, Children in the Classroom (circa 1950’s). He had to invent the genre; there was nothing really for him to look at. Invariably, the documentary maker wants more and more to turn into a presentational mode, so he moves to fiction. This happens with a frequency unheard of in the West.”

The 1950s also saw the emergence of Ogawa Shinuske, whom Richie considers to be the founding father of Japanese documentary filmmakers. A social and political radical, Ogawa directed a ten-hour series focusing on the farmer protests against the construction of Narita International Airport. Many of this new breed of political or social activist-oriented documentaries were never shown in theaters or on television. Tsuchimoto Noriaki’s important Minamata: The Victims and Their World (1972), about the mercury poisoning by a nearby chemical company of an entire community, suffered such a fate.

Films like the aforementioned now have a home in venues like the Yamagata Documentary Film Festival, founded in 1989. Other documentary festivals are getting underway in Kyushu and Hokkaido, and Japan is now very much aware of documentary traditions around the world.

Among the important documentarians working in Japan today is Haru Kazuo, who made a remarkable film called The Naked Emperor's Army Marches On (1987), which profiles an emotionally unstable World War II veteran who actively attacked Emperor Hirohito over the Japanese induced horrors of World War II. Kazuo’s idea of a documentary is that it has to be invasive, to an unusual degree. He was a pupil of Imamura Shohei, whose films specialize in this kind of abrasive, intrusive approach to Japanese life, and are highly critical.

In his next film, A Dedicated Life (1994), Haru Kazuo not only interviews leftist author Inoue Mitsuharu, but declares the man to be a born liar. Kazuo contrasts what the man says on camera with recreations of what had actually happened, as reconstructed by other people. The filmmaker utilizes a range of actors and actresses that he puts into the narrative framework of Mitsuharu talking rather grandly about himself, and the results are devastating.

Japanese directors like Kazuo have often had one foot in the documentary world and one foot in the world of fiction features. Both Ozu and Imamura made documentaries, although both are known primarily for their features. Richie notes, “There isn’t any rigid division between documentary, on one hand, and feature films, on the other, as discreet categories that do not overlap. Here they almost always invariably overlap. So you have a number of people who use documentary techniques, such as Shinozaki Makato, who realized that scripting is not enough to carry the weight in the 21st century. Watanabe Fumiki has made films about his life. He is rarely talked about in Japan, but he has scripted films using himself amidst a cast of actors. This sort of hybrid documentary approach has now become a standard for the best of Japanese film.”

“The most famous of these directors combining the best of the two genres is Kore’eda Hirokazu,” Richie continues. “In the case of Afterlife (1998), Kore’eda auditioned 500 amateurs, from whom ten were selected to appear in the cast. These ten were interviewed on film and their collective memories became the dramatic throughline of the film.”

At 77, Donald Richie has collected a treasure trove of memories, and his zeal for his adopted country—its culture, its commerce and, above all, its cinema—continues unabated. And Japan has returned the favor: Richie was recently awarded the 2001 Japan Prize. “When I started out, it never occurred to me that 50 years later, I was going to be getting prizes for having done work in a country which, when I came here, I knew nothing about. I didn’t really know I was going to be identified so closely with this country. And so this is a source of not only pride, but wonder.”

Craig McTurk recently relocated from Japan to Singapore, where he teaches documentary filmmaking.

Noteworthy Japanese Documentaries

- Sea of Youth (1966)—Ogawa Shinsuke, director

- Summer in Narita: The Front Line for the Liberation of Japan (1968)—Ogawa Shinsuke, director.

- Minamata: The Victims and their World (1972)—Tsuchimoto Noriaka, director.

- The Naked Emperor’s Army Marches On (1987)—Hara Kazuo, director.

- The Inland Sea (1991)—Lucille Carr, director

- Aga ni Ikuru (1992)—Makoto Sato, director

- Osaka Story (1994)—Toichi Nakata, director

- “A” (1997)—Mori Tatsuya, director.