Television: the household appliance that we love to hate. Children, parents, soap opera addicts, cable network managers, ad execs, reporters, producers, critics, scholars, spin masters, and stars of television all offer frank and revealing observations about their relationships with the tube in Signal to Noise: Life with Television, a documentary miniseries scheduled to air nationally on PBS July 11, 18, and 25.

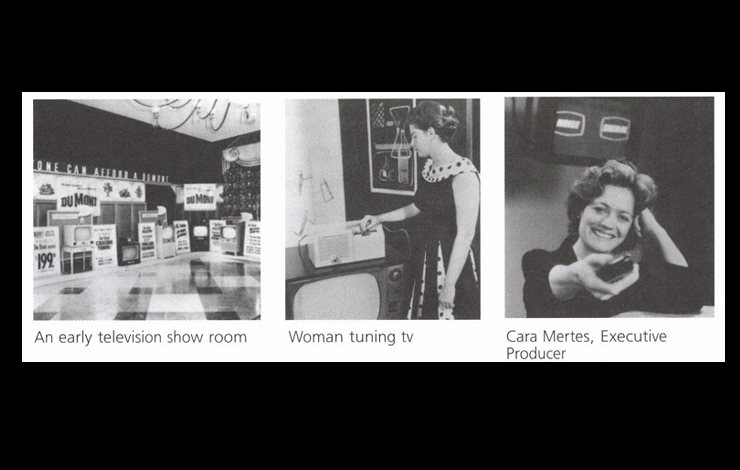

Producer/writer/director Cara Mertes commissioned 21 pieces by 17 independent producers and wove them together with archival footage and interviews to create a richly colored quilt of the United States at the end of the tv century. Produced by Mixed Media Projects for the Independent Television Service with funds provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Signal to Noise consists of three hour long segments. The first program, Watching TV Watching US, aims to show how viewers are the real product of television. TV Reality? is concerned with how and why television programming is constructed the way it is. The final program, Remote Control, explores the idea that what television does—sell us the future—is nothing new. ID's Dan Marano spoke with Mertes, an independent producer, consultant, and curator whose resume straddles the worlds of both television and avant garde video art; among other credits, Mertes produced the PBS showcases Independent Focus and the more experimental New Television.

How did Signal to Noise come about?

In 1993, ITVS put out a call for series, and I knew that they were interested in seeing something done on media. That led me directly to this kernel of an idea, something on the social, political, and economic implications of television. I knew that I wanted to work with a lot of independent producers, because that's what I had been doing in curating work, so I called several people whom I knew already and asked if they would be interested in doing a commissioned segment for a series about television. I chose most of those producers because they had already done work on media and some just because I liked their work and wanted to work with them. I put together a proposal with a steering committee, we went back to ITVS, and they gave us development money. We developed three hour long shows, cut down from four; that whole process took about three months, spread over a six-month period. After ITVS looked at the three full treatments and outlined each of the segment's general themes, they gave us the production money. Eighteen months after we signed the contract for the full production, we delivered the three shows.

Who came up with the title?

I did. I'm fond of technical titles; I called something I curated at Artist's Space here in New York Extended Definitions because when ED Beta first came out, it was called Extended Definition Beta. Signal to Noise is an engineering term indicating the ratio of signal to the background "noise." With electronic media, if you have too much noise, your signal isn't clear enough.

So what exactly did you find amid all those signals and eternal noise? Did making the series change your view of television?

I found that there was probably better television than I thought there would be before I started the series, and there is also a worse scenario for the future of television than I imagined there would be. I also found that people are extremely concerned about television's impact on their lives.

With the expansion of cable right now, for a while there is going to be a window of opportunity for people to get really creative, because there is such a demand for content; there is a real opportunity to propose things and get the work on the air. But for the work I am really interested in-very experimental-there was and is very little space on television.

The third episode looks at some proposed scenarios for the future of television, including its relation to the Internet. Is there a space there for more alternative work?

What we tried to say in the third show, which is about both the past and the future, is that if you look at the past of television, you see a tremendous potential, and everyone talking about it for more than 25 years, roughly 1919 to 1949, when television was released to the mass market. By then it had been more or less decided what would happen with television.

Look at the Internet: The conversation has been unfolding for 15 or 20 years, and now it's about to hit the mass market, by which time it will be pretty much decided the way things will go—that advertisers are going to pay for it, that it is going to be very consumer oriented, et cetera. It is the next big technology to come along since television, so we were trying to draw parallels between the two and say: All the hype is still there, all the potential is still there, but look what the choices are that each society is making, that each government and each international corporate entity are making about how this technology is going to be used. They can tell you anything they want, but look at the patterns. It really does boil down to who is going to pay for it and how is the technology going to be used in order to get it paid for. Whatever the answer to that equation is, that is what we are going to see on television and the Internet.

How did you develop and assemble the independently produced segments within the series?

We had 21 separate segments, for which I was working with 17 different producers. Initially I invited people to work with me, those people said yes, then I went away and I wrote a script, working with several other people. I went back to these producers and said, "Here is the script and here are the themes." In most cases I said, "Here is the specific idea, here are your characters, here is your location; now go shoot something, what I want you to do is write a script based on that." Then I would get a script back with these ideas incorporated in to it. I would often rewrite the script with the producer, tone it down, choose locations, work within the budget.

Then they would deliver a rough cut based on our conversations; very often that had to be recut. We then took that final rough cut and began to produce around the segments, in order to turn them into complete shows, as opposed to a collection of segments.

When I started out, I didn't think that the balance would be what it ended up being. I had originally thought the series would be 90 percent segments, 10 percent material that Signal to Noise produced. Signal to Noise ended up producing more than initially proposed, including interviews with tv viewing families, other interviews, and the graphics, and co-producing many of the segments. It ended up being 65 percent segments and 35 percent of our own material.

How long are most of the segments?

In shows one and three they are between six and ten minutes, in show two they are a bit longer.

Is it mere coincidence that you parallel the average seven-minute commercial television broadcast standard?

It is not a coincidence at all. There were a couple of reasons for that. First, we were gearing this toward a younger audience who is familiar with television conventions; second, the schedule that we were working on to develop an in-depth seven- or eight-minute documentary is not easy to do in the space of three to six months. We didn't have the time to give people the opportunity to develop a 15-minute piece, because these are not magazine programs, these are really mini documentaries.

In this country, at least, many people are unfamiliar with media literacy. Was it a guiding principle from the start?

Absolutely. The day that I said, "Let's do a series on media," the next sentence was, "Fine, then we should use media literacy principles, which ask: What are the social, political and economic implications of media, in this case, television? Who is making it? Why? Who's it for? Who is paying to have it made? What are the implications of the information kept in and kept out?" All of those are media literacy questions, and what media literacy does is put it into context, so that you can actually analyze the media that you are looking at; you are not just stranded there.

A number of people were working very hard to keep both the accessibility factor and the intellectual level very high, so that it wouldn't turn into a lecture series or merely cartoon ish examples of media literacy principles that are too simple for people to really engage with. [Senior Producer] Barbara Abrash, [Co Director] Norman Cowie, and [Editorial Advisor] Pat Aufderheide were three people I was working with since the very beginning. Norman is a producer and educator and comes at it combining theory and production. Pat is a journalist and educator and had ideas about how media literacy is really going to get across to people. Barbara and I came at it from a producing background that combined alternative media and theory.

You have to respect your audience, and that means you have to give them things; you know that they are as smart as they are about the media, particularly television. Everybody knows something about television from the time they are four; you can't assume people don't.

Did implementing that ever become too self-referential? There's that scene where [Media Education Foundation Executive Director] Sut Jhally talks about all the clutter that is off-camera and the hidden labor that goes into the composition, and your camera pulls out to reveal the entire crew.

I had him do that because by the beginning of the second show, I know that viewers want to be starting to deconstruct the series they are watching as they are watching it. I have often come across the question of how can you use television to deconstruct television; aren't you playing the same tricks on us that they are? It's a valid question, and if you want to engage with a large audience, I would argue that you have to use mass cultural forms to a certain extent to get your point across. What we hope is that you will be able to walk away and use these tools to examine any form, including the show you just watched.

The series is kind of a quilt of different documentary approaches and ways of taking an idea and translating it into a story. It contains traditional documentary form, personal essay, experimental text-based work, archival footage, documentary with the producer as the central character to get a point across; the series can be a model for how to learn to make documentaries. Almost every format that you can imagine was actually included in the show: pixelvision, 3/4", 35mm archival footage, VHS, Super VHS, some Super-8 footage. The interviews were all shot on Beta. We had to work very hard to make sure that it was all up to technical standards in our transfers. I am a great believer in the use of mixed media, hence the name of my company, Mixed Media Projects.

What else is Mixed Media involved in?

Right now I have just gotten a seed grant to start conversations around media and democracy, events around the country. Again, it is a collaborative project and there are a number of individuals working on it. The underlying questions are: How do media and democracy interact on a daily level?

How can you impact it, and how does it impact you? I am also developing a series on media in everyday life.

What is the plan for Signal to Noise after it airs on PBS?

Great Plains Network, which distributes Reading Rainbow, Newton's Apple, and several other educational PBS series, has taken an interest because of the media literacy movement in this and other countries. They see this as something that is going to catalyze a lot of teachers in high schools and colleges across the country, who will be able to take this into their classrooms and say, "Here's some really interesting and entertaining television that you are going to learn a lot from; you are also going to see the work of producers who are artists-not commercial producers-expressing some of their ideas." Based on prescreenings and festival screenings, there is a tremendous amount of interest from parents, educators, and students.

I would imagine there has been a good deal of foreign interest in the senes.

Japanese television has bought it, and a number of European countries have bought it. The way it is being sold is, "Here's what you have to watch out for in the coming years." Because global media are getting so much more commercialized and international in terms of the programming sold to different countries, it really provides a look at the media that might be in your own country in the next decade. Actually, when the foreign distributor he saw it, he said that he wanted to call it Here It Comes, Parts 1, 2, and 3.

He might try to acquire the rights to the Jaws theme...

That's an interesting thing, because we tried very hard not to make it a good-tv-versus-bad-tv scenario. That is a dead end argument. Television does some very good things, and a lot of people depend on it. I have been saying from the beginning that you can't turn television off. Even if you are not watching it, someone else is. It is affecting people in the society in which you live; therefore you have to learn to deal with it. I think that we have to become much more sophisticated as a culture in terms of the media that we produce and consume. That is the other thing that I think is very important about the series: it points to alternative kinds of television. It says there is the possibility for that, if we have the support and the infrastructure.

Which is where Signal to Noise begins, with [author and media professor] Susan Douglas tracing the history of television back to the time when commercial sponsorship was considered a very controversial notion. These are issues we see raised today, particularly with the Internet. The Internet is running on borrowed time; who will pay for its continued development?

That is the key question, and what can corporations sell to people in order to pay for it?

It is a complex relationship that, as with television, is in perpetual danger of being taken for granted.

In one bit that we didn't include in the first show, Sut Jhally talks about the fact that viewers are the workers in television and that viewers provide a lot of labor simply by watching. If, just watching, we are providing a service to someone, then we should be paid to watch television. That metaphor really puts you in the right relationship with television. You are doing a service for the advertisers, who want to capture your time.

We want people to walk away from the series, first, thinking differently about television; second, doing something-perhaps in their community-to become active in terms of their relationship to television; and, third, possibly producing. We hope the show will make you ready to write

your legislature, or produce your own work, or at least be interested in the prospect. Although we tried very hard to stay away from promoting specific approaches, legislative or otherwise.

We even tried to stay away from the idea that public television as it now stands is precisely what we are looking for. We tried to suggest that a television for the public is a good thing, but that in certain ways, we need to reformat even the public television that we have.

Dan Marano is one of the producers of the Taos Talking Picture Festival which exhibits film and video and examines their impact on culture.