Enjoying its second year in the city center, the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) thrives as a multi-layered event, offering up so much richness that one person cannot absorb it all. Forced to choose among some 300 documentaries, including 12 competitive categories, one can reach overload just by reading the program. Then there are the special screenings: master retrospectives, this year including films from Frederick Wiseman, Hubert Sauper, Nick Broomfield, Wim Wenders, Lixin Fan, Julien Temple; the 2014 IDFA Tribute to Heddy Honigman who, as is customary for the honoree, selects her own “ten best” documentaries by other filmmakers; Queer Day; the screenings from IDFA Bertha Fund, dedicated to stimulating and empowering creative documentary in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and parts of Eastern Europe; and more.

The festival runs for 11 days. In six days, I did not have time to see enough films, let alone contemplate getting to the DOCS for Sale buyers’ market at the videotheque; the vaunted invitation-only commissioning editors’ Forum, in which 50 projects from 20 countries were pitched; IDFA Academy, which shepherds emerging filmmakers through a unique program; Green Screen Day; the OXFAM-sponsored special Expert Program, which included activist/author Naomi Klein presenting her new book, No Time; or the Kids and Docs section (Making documentaries for children is seen as a hot “new” field, despite the fact that educational producers and distributors have been successful with children’s films for decades).

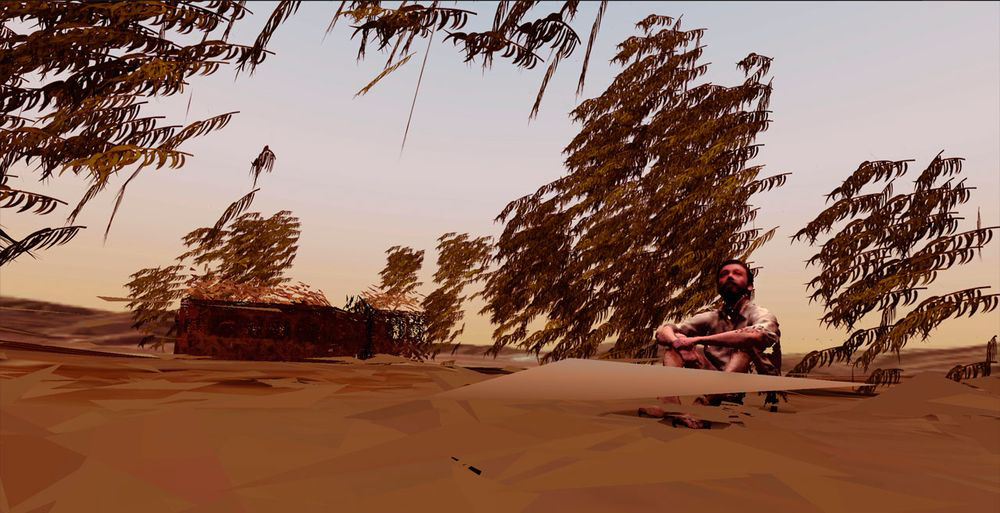

From Oscar Raby's Assent (2013)

It’s possible to have a meaningful IDFA experience without ever seeing a film, since there are series of Industry Talks, a documentary-themed museum tour, a concert series, even a special festival canal boat trip. And then there are the parties: every afternoon the “Guests Meet Guests” throng of body-crushing from 5:30 to 7:00 p.m., this year at the convivial canal-side Café de Jaren, whose endlessly patient staff deserves special kudos; later private get-togethers held by the likes of Sheffield Doc/Fest and “the Canadians,” who are always out in force at IDFA; and dinners with friends and colleagues from all over the world. For the truly stout-hearted, there are late-night festival dance parties.

"Guests Meet Guests" is a must. Unlike the vibe at some festivals, this is ecumenical. If you have a guest badge, you get in. On nights when the wine and beer are free, it is festival fever at high pitch. Seemingly everyone turns up sooner or later, from IDFA director Ally Derks and industry heavyweights like Anna Glokowski (France TV), Nick Fraser (BBC Storyville) and Diane Weyerman (Participant Media) to Thu Thu Shein, director of the Myanmar-based Wathann Film Festival. It’s possible to have a conversation over the din with almost anyone.

So what did I do in visitor-friendly, documentary-drenched Amsterdam? I met friends new and old, watched films, participated in formal discussions, and, most excitingly, plunged into virtual reality documentaries. For some, “new technology” and VR may seem to be only whipped topping, but IDFA takes it seriously, devoting resources to a new DocLab “Industry and Training Academy,” ten days to the DocLab Expo and a day-long DocLab Summit. IDFA’s DocLab has been operational since 2007, with a mission: “To showcase interactive documentaries and other new digital art forms that successfully push the boundaries of documentary storytelling in the age of the interface.” One might quibble with the New Media moniker, since the 2014 winner of the Award for Interactive Storytelling was the very popular podcast Serial. Although special and interactive in the sense that it boasts a huge fan base that creates original Web spinoffs, Serial is an iteration of 1920s radio serial mysteries, albeit one based in fact. It is newish content in a time-tested format. However, after decades of waiting, it’s here: the ability to create and experience meaningful narrative and atmospheric documentary pieces, thanks in large part to Oculus Rift, the VR technology company owned by Facebook.

From James George and Jonathan Minard's Clouds (2014)

The works presented in Oculus Rift manifest a serious change in technological and aesthetic approaches to nonfiction. It is as earthshaking as the coming of sound or the portable synch-sound camera/tape systems of cinema vérité/direct cinema. And we may well have cause to be concerned. VR is addictive, and might become as commonplace as mobile phone videos, since consumer versions go on sale in 2015. The first public targets are gamers, whose affinity for a training technology that is used extensively by the US Department of Defense is a natural. For documentary makers, the new sensory spaces opened up by the technology will reposition the same ethical and artistic questions that have beset the field since Robert and Frances Flaherty gave us Nanook of the North.

Experiencing VR can easily become an obsession. In the DocLab VR Screening Room, one could make an appointment to sit down, put on the headset/earphones and enter a filmmaker’s universe. Projects included Zero Point (2014 USA), by noted war photographer and Academy Award-nominated documentarian (Hell and Back Again) Danfung Dennis. Zero Point is a 20-minute history and introduction to VR. In this respect it is like many sponsored industrial/informational films. However, it is shot in full 360-degree video specifically for Oculus Rift. Clouds (2014 USA), filmed using a new 3-D format called RGBD, was created by James George and Jonathan Minard entirely from open-source software. It is what one might expect in a code-driven piece: lovely abstract images and emphasis on algorithms meshed together in an endless conversation made interactive by the viewer staring at different spots to elicit different responses.

Assent (2013 Australia), which won the Interactive Audience Award at the 2014 Sheffield Doc/Fest, takes the form to another level. Oscar Raby created a historical documentary portrait that works on many levels. As he describes it, “In 1973 my father witnessed the execution of a group of prisoners captured by the military regime in Chile, the Army that he was part of. Assent puts the user in my father’s boots…as we walk to the place where that happened.” The piece raises questions for serious filmmakers, as VR can envelop one’s senses and make surroundings and events almost palpable. How does the maker immerse his audience in a genuinely tragic personal situation, a re-enactment of a historical event, without exploiting the audience’s involvement in the gruesome killings? In Assent Raby uses lower resolution visuals to create a stylized forest environment. Yellow leaves rustle as one walks through the forest listening to Raby speak with his father, and the firing squad death imagery is not “realistic.” Still, the shock of being a part of the violence is a jolt to the system. A first-time user should probably choose a different VR documentary.

From Strangers: A Moment with Patrick Watson (2014)

Strangers: A Moment with Patrick Watson (Canada 2014), by Felix Lajeunesse, Paul Raphael, Chris Lavis and Mark Szcerbowski, poses an opposite question for VR. It is so nice inside this mellow documentary that one may not want to leave. Produced with state-of-the-art 3-D and 360-degree cinema, Strangers offers the chance to sit with Watson in his homey Montreal loft as he noodles on the piano for his dog, and for you. As the catalogue describes it, the work “… is a medium that doesn’t have to tell a story or provide interactivity. Strangers simply invites you to be part of the moment.”

Betsy A. McLane is the author of A New History of Documentary Film, Second Edition, which comes out in May through Bloomsbury/Continuum.