Bond trader Peter Staley, diagnosed with AIDS-related complex in 1987, heard his mentor at work say all the infected " ‘deserved to die because they took it up the butt.' I was deeply closeted and I had to just stew about it for the rest of the day. I got myself to the very next ACT UP meeting--they could just tap into that immediate anger and get stuff done."

Thus began Staley's transformation from Wall Street wunderkind to full-time AIDS treatment activist, chronicled in David France's superb debut documentary How to Survive a Plague. The film covers the youthful, over-the-top actions of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) during the period 1987 to 1995. Staley is one in a large cast of people in the film who were radicalized by the plague and the refusal of the US government, from the president to the National Institute of Health (NIH) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the private sector to provide leadership in combating it. This radicalization took the form of becoming their own medical statisticians, drug-trial protocol writers and advocates for lower-priced drugs. Members of the Treatment and Data Committee of ACT UP distributed glossaries and their own impressive treatment research agenda and sold pre-approved drugs. Even the NIH was subscribing to their publications.

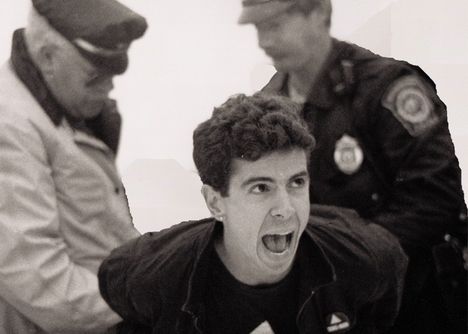

While the film's main focus is on the treatment-activism branch of ACT UP, we also see ACT UP's other specialty--edgy happenings that launched AIDS activism into media prominence and political discourse. There's the 1989 St. Patrick's Cathedral die-in in Manhattan, where Archbishop John Cardinal O'Connor was officiating and then-mayor Ed Koch was worshiping. We see Bob Rafsky heckle Bill Clinton during a campaign speech for refusing to promise action on AIDS, provoking the candidate's notorious claim, "I feel your pain." An open-casket funeral for Mark Fisher becomes a march to George H. W. Bush's campaign headquarters, where Rafsky pronounces a curse on Bush for his inaction. Weeping over memorial quilts has its consolations, but there's nothing quite as powerful as watching dozens of survivors hurling the ashes of their loved ones onto the White House lawn.

As the title of this doc plainly states, it serves as a manual for more recent movements for systemic change such as Occupy or Pussy Riot. We see numerous examples of ACT UP's laborious strategy of leaderless, broad-consensus decision-making. Director France also doesn't shy away from showing how ACT UP degenerated into internecine squabbles and factions. The Treatment and Data Committee split off and formed the Treatment Action Group (TAG), a "think tank-type project" that participated at AIDS conferences and was criticized for getting too close to the powers that were, especially when TAG members opposed accelerated approval processes for drugs. How to Survive a Plague shows how an aggressive, youthful organization overcame their differences and made long-term changes that saved millions of lives.

France doesn't mind its being considered an instructional video, but he would prefer to call it a medical thriller. That is what he says distinguishes his film from two other recent documentaries about AIDS activism, Vito and United in Anger: A History of ACT UP, which were made by friends of his. "Mine has a more traditional movie form with a three-act structure, a linear narrative," he maintains. A counter marking the rapidly rising worldwide AIDS death toll each year functions as urgent chapter headings. We don't know which of the vibrant young men caught on videotape early on will be dead by the mid-1990s.

Happily for chroniclers of the time, the rise of AIDS coincided with the birth of the consumer camcorder. The feverish recording of every ACT UP meeting, demonstration and informational tutorial gave France an overabundance of contemporary footage--he credits over 30 videographers. He found some of it in the New York Public Library's AIDS Activist Videotape archive, but much of it was in the hands of private collectors. Sadly, he often negotiated not with the videotapers themselves but with their estates.

France himself is in many of those videos, since he was covering the AIDS crisis as a journalist from its earliest days. (He wrote the first feature article about ACT UP, in the Village Voice.) But he was strictly an observer and documenter: "I'm pressed flat against walls, mostly behind pillars or a truck, trying to be ears and eyes and nothing else," he recalls. "Mainly I had a desperate fear of the epidemic. Like most people, I was paralyzed by the plague. Most people were so passive and terrified, which made what [the activists] did that much more remarkable."

France had an inspiration for documenting the civil-rights crisis of his own time. "I saw Eyes on the Prize, which was a life-changing documentary experience for me," he says of the 14-hour series on the African American civil rights movement. "It wasn't just a story about the lack of civil rights, but a story about a movement of people who collaborated to bring those civil rights. I recognized that AIDS treatment activism was the next inheritor of the civil rights movement after the feminist movement and was, in fact, the last great social justice movement in America. It hadn't been examined that way yet. What did they leave us? What's the legacy that we have inherited as a culture from that social justice movement?"

There is a clear link between AIDS activism and more recent struggles for civil rights. Instead of making an explicit connection, the film uses the metaphor of lives lost in a war. Late in the film, we are exhilarated to see how the breakthrough of the triple-drug combination in 1995 saved many of the men we were sure would be dead by its conclusion. But one of them voices the eternal warrior-survivor's question: "So many good people [died] . . .Like any war, you wonder why you came home." In his praise for this film, political commentator Andrew Sullivan says, "None of it would have happened as it did, if we had not been radicalized by mass death, stripped of fear by imminent death, and determined to bring meaning to the corpses of our loved ones by fighting for the basic rights every heterosexual has taken for granted since birth. No spouse was ever going to be turned away from his husband's death bed again, as far as I was concerned. . . For me, marriage equality is not an abstract concept. It has always been my attempt to make my friends' deaths mean something more than tragedy." David France's document of the plague years and of the victims-turned-experts who fought to eradicate them provides future civil rights wars with a protocol for action.

How to Survive a Plague opens in theaters September 21 through Sundance Selects.

Frako Loden is adjunct lecturer in film, women's studies and ethnic studies at CSU East Bay and Diablo Valley College.