A map of Lower Manhattan... A mini-umbrella for unexpected spring thunderstorms... Comfortable shoes for pounding the New York sidewalks... And of course, caffeine.

These were the must-have items for attendees at the 2005 Tribeca Film Festival, which in four short years has grown into a big city fest with an intimate neighborhood vibe. While Tribeca still seems to be figuring out its core identity, it has successfully emerged from its post-9/11 roots into an incredibly well-marketed, organized event that is here to stay.

Tribeca almost seems to be building itself by working backwards. Most festivals become household names when a film they've premiered becomes a hit with general multiplex audiences, and the media then starts to pay attention.

At Tribeca, just the opposite seems to have happened, in no small part because of the savvy mix of marketing, sponsor money, star power and its 9/11 origins. National ads featuring founder Robert DeNiro and Ellen DeGeneres, a short film competition with partner Amazon.com and festival banners plastering everything from street corners to taxi cabs have quickly catapulted this festival into the public's consciousness. Tribeca seems to be using this spotlight to lure desirable projects, positioning itself to the film community as a place where one can get lots of attention for one's film.

Says festival programmer David Kwok, "I think the reason it's become so successful so quickly has a lot to do with the founders' vision: starting out big, having the goal of putting Tribeca--the neighborhood and the festival itself--on the festival map from the get-go."

"Big" is an understatement. With 158 feature-length domestic and international features playing over 10 days and a variety of programming sections whose focus are not always clear, trying to figure out what to see can be daunting. Add the festival events, parties and panels to the mix, and it becomes an exercise in prioritizing and scheduling. Kwok says that the festival is "trying to be a completely international film festival that can serve the American side as much as the international side. Because it's so diverse here, even if we get criticized for that, that's part of our mission--to serve as many people in New York as possible and give everybody a taste of something different."

With this in mind (and subway map in hand), I set out to sample the Tribeca smorgasbord. My first bite off the documentary plate was Jeppe Ronde's lyrical The Swenkas. The film is a father-son story set amidst the world of the Swenkas, a small group of working Zulu men in post-apartheid South Africa. Every Saturday night they slip out of their grimy work clothes and dress in their finest Western suits to "swenk"--compete in private fashion shows for money. The participants are judged not just on their clothing, but also on their overall style and presentation.

On the opposite end of the societal spectrum was The American Ruling Class, "the world's first dramatic-documentary-musical," which played in the " NY, NY Documentary" section. A bold hybrid experiment, the feature-length satire combines scripted material with the traditional documentary form to explore the question, "Does America have a ruling class?"

Lewis Lapham, the renowned essayist and author, narrates as he plays mentor to two recent Yale graduates. They attend Pentagon briefings and New York society dinners; visit the World Economic Forum, philanthropic foundations, law firms, corporations and banks; and interview everyone from Bill Bradley to Mike Medavoy to William Howard Taft IV, as they explore class, power and privilege in a supposedly democratic United States.

The catch? The grads aren't real people; they're archetypes constructed by the filmmakers and then played by actors. And the majority of the people interviewed are in on it. While I admired the filmmaker's use of unconventional elements to explore a compelling topic, I felt cheated by the fact that I didn't know if what I was watching was candid or scripted.

I got back to basics with pioneer filmmaker Robert Drew's personal From Two Men and a War, about his experiences as a young fighter pilot in the Army Air Corps during World War II. Early in his training he met the celebrated war correspondent Ernie Pyle, who inspired Drew to create films that would really let people know "what it is like to be there," just as Pyle's reports did.

Paradoxically, in telling his own story, Drew embraces techniques in From Two Men and a War that go against the cinéma vérité style he helped to develop. The film uses extensive narration, reenactments and stills with music. "I think he's a practical American who knows that you adapt aesthetics to circumstance," Tribeca executive director Peter Scarlet explains. "It has a narrator because that's the only way you can tell a story about your own life... This film is one of the most outstanding films I've seen this year."

Audiences had the opportunity to hear from the front lines of Iraq in the intense A&E IndieFilms documentary Bearing Witness, from Barbara Kopple, Bob Eisenhardt and Marijana Wotton. The film tells the stories of five female war correspondents at different stages of their careers, and explores topics such as the inability to have a personal life, methods for dealing with fear and the challenge of getting their stories on the air without having them watered down by networks.

The validity of the news was front and center at the "Where We Get Our News...Now" panel, which was moderated by Time Managing Editor Jim Kelly and featured Eugene Jarecki (Why We Fight), Rory Kennedy (Moxie Firecracker Films), Charles Lewis (president of the Fund for Independence in Journalism) and Jessica Sanders (After Innocence).

In a spirited discussion about why more and more people seem to be turning to documentaries as their source for in-depth news coverage, the panelists and the audience went back and forth on such topics as whether point of view in a documentary helps or hurts; the effects of over-processed, homogenized news broadcasts; whether the country is red, blue or purple; and how to tell the truth when it seems "everyone is lying."

Said Kennedy, "With documentaries, like most news, it's hard to say that there's a single objective truth in regard to anything, so for me, fairness--being balanced--is more of an objective." She and Sanders both agreed that if you let people express their own interpretations rather than trying to force a particular truth, an overall sense of fairness regarding the story will emerge.

Of the rising popularity of documentaries, Kelly noted, "What I have noticed is that consumers of news are rejecting processed information or information they feel has been processed for them, and wanting to get at what they feel is the real story. That is why blogs have become so popular. It's not so much people feeling the media is liberal or conservative or whatever. They want a direct connection to it. The vision of a documentarian making a film seems like they're tapping into something genuine."

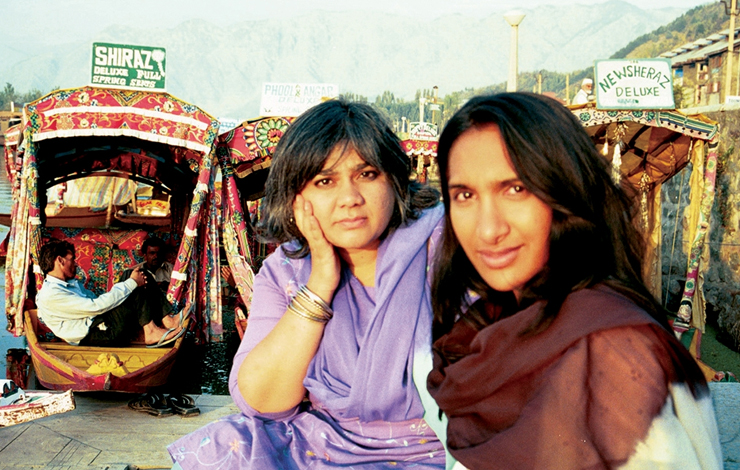

One of the authentic projects you may be hearing about in the future is Senain Kheshgi and Geeta Patel's Project Kashmir, which was part of the Tribeca All Access program. TAA provides opportunities for filmmakers of color to connect with film industry executives.

Kheshgi, a Muslim, and Patel, a Hindu, were born on opposite sides of the dispute between Pakistan and India. In their film, the two American friends take a journey to Kashmir, considered by both to be the most beautiful and dangerous place in the world, and explore whether friendship can bridge the societal barriers formed by long-held prejudices.

"This is really such a gift," Kheshgi says about her TAA experience. "They pay for your flight, they put you up, they set up panels, they do a welcome lunch. They really embrace you as emerging filmmakers."

Kheshgi notes how the documentarians in the program were very supportive of one another, where the narrative filmmakers often were more competitive. "We are such an amazing community of caring people who want to see each other succeed, and that's been the best thing about this. They're introducing us to people who not only want to help us make our films, but also just give us advice on how to make them, so it's the help and the how."

At press time, Ross Kauffman (Born Into Brothels) had officially signed on as a producer, and Kheshgi and Patel were planning on one final eight-week shoot in Kashmir before heading into six months of editing.

Kheshgi's experience seems to have fulfilled Scarlet's goal for the festival. "I would like people to have a memorable and pleasant and positive experience," he says. "I believe a festival is about meeting and encounters and discovery and hospitality." Referring to the tender age of the festival, Scarlet adds, "When you ask a four-year-old, What do you see the future as being? Usually the four-year-old tells you they can't wait to grow up. This four-year-old is enjoying being a four-year-old."

Tamara Krinsky is associate editor of Documentary.