Saving the Odd Docs: Hybrid Media Like 'Wholphin' and 'GOOD' Distribute Rare Films

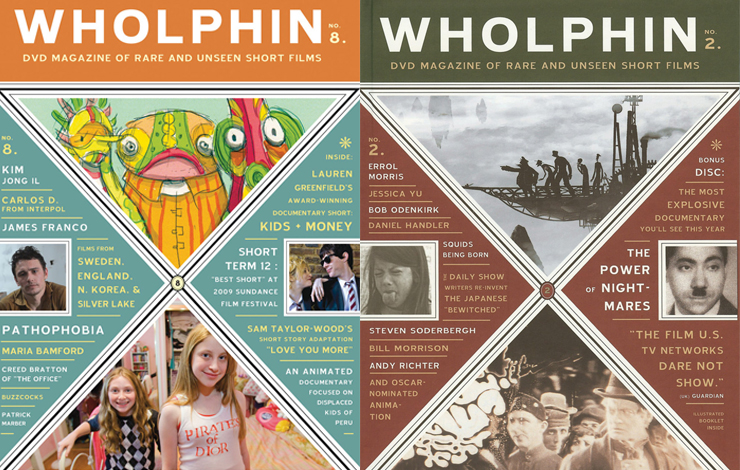

Covers of Wholphin, the magazine/short film distributor hybrid

A wholphin--by definition, "a hybrid cross between a 400-pound bottlenose dolphin and a 4,000-pound false killer whale"--may sound like some schoolyard myth, but is, in fact, real. Also real are the countless filmmakers toiling away to make their visionary labors of love, only to have them be seen by a handful of loyal loved ones. That is, until recently, when the convergence of new technology, the Internet and cinephiliac visionaries has allowed for new hybrids of mediated content to reach viewers like never before.

Fans of hipster lit are likely to be familiar with Wholphin, a quarterly digest in DVD form, which features a wealth of rarely seen gems, from short works by A-listers like Steven Soderbergh and David O. Russell to re-scripted Russian sitcoms. Launched in January 2006, Wholphin's objective is, according to editor and head curator Brent Hoff, to "provide a home for films that for various reasons get lost in the media sea and remain largely unseen." Hoff started Wholphin with his friend Dave Eggers, known to legions of readers as the founder of the more-post-modern-than-thou literary journals McSweeney's and The Believer.

Says Hoff, "We had both come across these incredible films that had disappeared because they were either too short to show in theaters, too odd to show on TV, or too politically controversial to show anywhere. Somewhere between YouTube and Viacom there was a whole new emerging species of film being made without regard for the various time and content constraints of TV, film studios or the Internet." The first issue of Wholphin was a success of the "Why hasn't anyone done this before?" variety. Content including Spike Jonze's "lost" Al Gore documentary and David O. Russell's banned anti-war piece Soldiers Pay made its popularity almost a no-brainer.

Though Wholphin is not an event-driven publication, programs all over the world have showcased its content. The first of these, at the Brooklyn Independent Cinema Series in Park Slope, played to a packed house. In addition, Wholphin offers Web-only content that Hoff says is not much different in form than that selected for the journal. Though he is aware there is still a stigma attached to streaming online content ("I know a lot of serious people still view the Web as a down-market outlet for silly Bush parodies or whatever") Hoff feels www.wholphindvd.com does offer "a great selection of films, including 30-minute docs and pieces by established directors with full liner notes and interviews."

Hoff notes that the name is the perfect metaphor for the type of work he aims to transmit. "Unlike most hybrids, wholphins produce fertile offspring and yet, hardly anyone has heard of them, much less seen one," he maintains. "One would hope the fate is not the same for independent films." Though the idea is innovative, it is also strangely old-fashioned, relying on a subscription model in which people sign up to receive all of the issues for $40 a year. "Wholphin is hard to pronounce, difficult to spell, and no one has any idea what it means or how it relates to what we're doing, but it's just right, somehow," Hoff admits.

In a similar vein, yet fueled by perhaps a more idealistic mission, is GOOD (http://www.goodmagazine.com)--at once a print magazine, DVD journal of features and documentaries, Web-based publication, charity and event-driven organization. Think Wholphin as run by Robert Greenwald. GOOD was born out of the coupling of Reason Pictures, a traditional film production company, and GOOD Magazine. According to Bristol Baughan, head of documentary content, "We hope to be able to hear an idea or pitch from filmmakers, writers and innovators, determine who the audience is and how best to serve them, be it online video, magazine, feature films."

Issues are built around themes with a political bent. Past issues have included "I Heart America," "Change is Good," "Media Issue" and "For the People." Says Baughan, "The spectrum of what inspires us is wide and hotly contested. My inspiration comes from studying international relations and feeling that the stories trapped in textbooks could be more mainstream if told by a great storyteller. We are all pretty inspired by people who figure out a way to do something they love, make a good living and add a bit of value to the world." Specific organizations and individuals the company looks to include a diverse array of innovators such as Darren Aronofsky, Colors Magazine and The New Yorker.

In addition, GOOD produces feature films. The company's first documentary, famed British director Michael Apted's The Power of the Game, a look at the world through the lens of soccer, premiered at this spring's Tribeca Film Festival. Currently, the company has four docs on its slate: an untitled look at the 2008 election featuring Edward Norton; Oscar-nominated Marshall Curry's latest effort, Racing Dreams; Rebecca Cammisa's Which Way Home; and Alex Gibney's Burning Down the House, in partnership with Participant Productions.

The upcoming summer issue's cover story profiles 11 Gen X veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. It is a striking story along the lines of Patricia Foulkrod's The Ground Truth, featuring the faces, words and voices of what one might call "the new veteran"--men and women of our generation or younger already dealing with the traumatic wounds of a war whose validity is being increasingly called into question. Along with the print interview, GOOD and filmmaker Lindsay Utz produced a documentary video of interviews with the 11 subjects, and all elements of design and aesthetic are unified, making a complete multi-media package.

Ideas at GOOD are developed and cultivated by its team, rather than simply plucked out of a pile of open submissions. Says Baughan, "We have development meetings as often as we can and sit everybody down to discuss what issues and stories we are interested in and what we think our audience would want to watch or read. The Power of the Game started with a political science paper that founder Ben Goldhirsh wrote at Brown. He was interested in how few universal laws exist in the world save those of the International Football Federation (FIFA). Now we tend to seek out filmmakers who we respect and share our sensibility and have a dialogue about what we are both interested in digging into."

Like Wholphin, GOOD works on a subscription model, with subscribers paying $20 a year for all issues. However, that $20 does not go into the big pockets of wealthy investors; instead the subscriber gets to pick which of the 12 charitable organizations with which GOOD partners will get their money. These include Ashoka, Creative Commons, Donors Choose, Generation Engage OCEANA, Room to Read and Teach for America. In addition, GOOD's events, which attract crowds of engaged and active subscribers, highlight local business and charities.

So what's in it for the filmmaker? For the established filmmakers with whom Wholphin works, including Bill Morrison, Errol Morris, Jessica Yu and Alexander Payne, the digest is simply a way of intercepting work before it dissolves into the cultural ether, and presenting it to appreciative eyes. For less established artists, Wholphin and GOOD provide initial platforms to show short content that might propel them into the film lover's consciousness, providing a launching pad for a long career.

Unlike at GOOD, Hoff veers away from sticking to a particular theme. "Finding amazing unseen films by theme is hard," he admits. "I don't ever want to be trapped into putting out a not-so-good film about beards on an issue solely to show everyone how clever I am for coming up with a beard-themed issue. That said, we do have four great films about beards and are just waiting for that magical fifth."

As for financial compensation, Hoff says, "We try our best. We pay a little and have now begun building royalties into the agreements for online and possible TV distribution as well." Baughan declines to give specifics on the company's compensation structure, noting that "GOOD is a start-up business that seeks to create content that our audience wants to watch and advertisers want to brand themselves with. We believe that our sensibility, matched with great production value, can compete with niche and eventually mainstream media." Regarding rights, each project is negotiated differently, but filmmakers should make absolutely sure that all of their music is cleared.

Though they overlap in some respects, Wholphin and GOOD are different enough that both are sustainable in what many consider to be an oversaturated media landscape. Baughan expresses her admiration for Wholphin, noting, "We share a similar penchant for great content and talented artists. We are pretty different in that we are a film, video and live event development, production and financing company, website and print magazine pushing content we think is relevant as well as commercial." Still, both ventures have one thing in common: the Al Gore stamp of approval. The former US Vice President and global warming activist is fully humanized on the cover of the first Wholphin issue, frolicking in the waves with his family at their summer home; shortly after, he and his wife Tipper attended GOOD Magazine's 2006 Bastille Day event, schmoozing with more than 600 subscribers. Looks like the hybridization of media is beginning to become a convenient truth, indeed.

Danielle DiGiacomo is a Brooklyn-based journalist and filmmaker who is currently editing her first feature, Island to Island: Returning Home from Rikers. She works as the documentary film coordinator for Indiepix.net.