Singing the Body Eclectic: Simon Pummell Discusses the Diverse Imagery of His Mesmerizing New Documentary

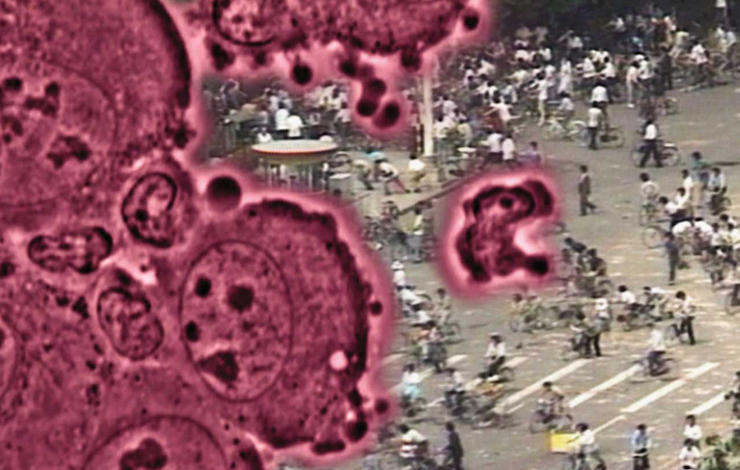

One of the more entrancing documentaries on the festival circuit this year is Bodysong (Simon Pummell, dir./wtr.; Janine Marmot, prod.), a poetic depiction of human life told through moving images from the last 100 years of cinema. Life in all its glory and infamy—birth, love, sex, violence, disease, dreams and death—is portrayed through a collage of diverse, rare images gathered from around the world. Newsreels, home movies, amateur porn and medical and educational footage are all cut to a lyrical score by Jonny Greenwood of the band Radiohead.

The result is a vibrant cinematic mosaic, sometimes haunting and disturbing, sometimes exhilarating, joyful and comic, but always enthralling. Underscoring the paradox of the uniqueness of each single individual life and the common bonds of human existence that span across ages and cultures, this expressive collage is the visual equivalent of John Donne's "No Man Is an Island."

The film is paired with an award-winning website, www.bodysong.com, where the origin of each shot is given, and its visual and historical significance explored.

International Documentary interviewed by e-mail London-based director Simon Pummell, whose credits include numerous animation and short films, about his motivations for creating such a striking feature debut.

What was the inspiration for the film?

Simon Pummell: I guess Bodysong came from two very different moments. One, when I admitted to myself that I was as often more intrigued and emotionally affected by moving images I saw outside the cinema—in a hospital or on the Net or on a family home movie screen—as when I went to the "movies." And so I found myself asking, If you were able to look back from the vantage point of 500 years in the future, what would "movies" have captured that was really profound, exciting, still worth looking at?

The second was the birth of my son, which was the same utterly unique, personal, astounding, emotional experience it is for so many millions of people. And that made me think about this paradox of experience as unique and the ebb and flow of life one shares with millions of others.

One dream starting point was that I wanted to make a film I could show to anyone, and they would recognize something of themselves. The other dream starting point was to compose a new perspective for the audience. What has come to be about making a pretty picture was originally about moving things forward and backward in the narrative, and juxtaposing elements in ways that heightened their narrative relevance—and that is what Bodysong does.

Why is it entitled Bodysong?

I chose the title intuitively, but it was very much reinforced when I found the Joseph Campbell quote: "Mythology is song. It is the song of the imagination, inspired by the energies of the body... And the only myth that is going to be worth thinking about in the immediate future is one that is talking about the planet, not the city, not these particular people, but the planet and everybody on it."

Was it difficult to get funding and financing for the film?

I had been developing another feature project when I conceived Bodysong. But Bodysong just really pushed the other project aside; it grabbed my imagination and it grabbed other people too, so the whole development period was quite fast and exciting. We took the film to FilmFour in the UK, and they put it into development and were incredibly supportive in getting the film made. As part of the "development and writing" process, I created a CD-ROM as well as a traditional "paper" screenplay.

The main difference between realizing this film and my shorts was the amount of discussion there was with financiers about the film as it took shape in development and in the cutting room. That discussion process is part of the form, and I think improved the film.

Did you already have a narrative structure when you began to look for footage, and did that guide you in the search for archival material? Or did the research and the narrative process work in tandem?

Initially I wrote a detailed script, and we made a CD-ROM to demo a couple of sections of the film. Once the film went into production, a team of researchers started a massive trawl for footage; we broke the film into about 50 chapters and searched section by section to make the task manageable.

We broke down the script, and the researchers sifted through thousands of hours of images for the telling moments. We were running three cutting rooms: Two assistant editors spent all day selecting possible footage for me to view, and in the main cutting room, Dan [Goddard, the editor] and I shaped it.

Once we were in production, I asked the research team to look for very specific activities and footage, but to particularly grab anything that moved them or excited them or which seemed to exceed the brief, because of course in the process of searching they often found material richer and more unexpected than I could plan for in the initial writing.

Can you discuss the task of finding such a wealth of vast and diverse material?

The core team of researchers, led by two very experienced archive specialists, Ann Hummel and Aileen McAllister, was about half a dozen, but our researchers also enlisted the archives as our allies and asked them to not just find footage we requested, but to actively tell us about footage they were enthused and passionate about. The combination of the archives actively supporting the project and our research team spreading their search to archives across the globe and to research centers and other unconventional sources gave us an incredible avalanche of interesting footage to build from.

The whole project took two years. But it would have taken much longer apart from the fact that we worked on research and cutting simultaneously. The first assembly of the film we made chronologically, and the researchers were always only a couple of chapters ahead of our assembly of footage.

What was the most difficult part to edit?

There was a moment in the process when I would dream fast-forward ribbons of images all night. I think everyone on the team had a moment of nausea at some point-just looking at so many images, often so emotionally charged, was very intense. We were looking for the patterns, the hidden signs, the connection with the story, and sometimes we would receive incredible gifts—footage that somehow created links we could only have dreamed of. My favorite was the shot of Helen Keller as an old woman re-enacting her first spoken sentence, "I am not dumb now." The joy on her face and the sentence she speaks and the near mythic event it re-enacted became the touchstone for the section of the film about the human capacity for language—and communication.

By far the most difficult part of the film to edit was the later stages of the violence and war section. Both the responsibility of using such images and the often really harrowing content of those images was quite crushing while we worked on that section.

Were you always planning to tell a story purely through images and music? A documentary of this kind, without narration or dialogue, is not unprecedented. There's the Godfrey Reggio's 'Qatsi' trilogy (Koyanasqatsi, 1983; Powaqqatsi, 1988; Noqoyqatsi, 2000), as well as Baraka (Ron Fricke, 1992) and Berlin: Symphony of a City (Walther Ruttman, 1927). Did you view these films as models, as inspirations?

Yes, these films all inspired me, partly formally, partly in that I admired Reggio's boldness in taking quite experimental techniques and making them work as a movie.

The Philip Glass music is an integral part of the Reggio films, and the same can be said about Jonny Greenwood's score. What was it about Greenwood's work with Radiohead that convinced you that he was the right person for this project?

I love Radiohead's music, the depth and richness of it, so they were always our ideal music "casting." We approached Radiohead through their music publisher, who was really enthusiastic and supportive. He felt Radiohead might consider this film project as it was so very different, and that its concerns and interests might chime with them. Then after Jonny had looked at the CD-ROM and was interested in the project, we met up.

How did you work together? How did you communicate the "musical vision" of the film?

When Jonny agreed to do the project, I knew the music would have the emotional power and stylistic range the film needed. From early on we agreed to create the picture track and soundtrack very organically. We worked in parallel, sending each other very rough versions of the both sound and music, and allowing the combinations to evolve. He would send me rough mixes and I would send even rough assemblies of footage sometimes so he could get a sense of the universe and mood of particular sections.

Very early on we talked a lot about the emotional journey of the film, the emotions the spectator would pass through, and Jonny transformed those different emotional highs and lows into music, into the massive range of musical idioms and soundscapes.

I was very impressed by your website; it supplements and complements the film. Delving into and exposing the story of every shot is a very innovative concept. How did you come about this idea?

The movie is interested in what we derive from images when we are not insulated by the normal immediate context of 'anthropological information' or television voiceover. Remove this and the viewer is forced to look more freshly at the shot.

The website creates a 3-D space where the story of the movie—every shot—hangs in space. You can fly along the timeline of the whole movie, see the shots in the film, and if you click on a shot it opens and tells you the story of that individual shot.

The site also has another version of the film's music as sets of samples and loops, which play as you move through the film. So you can really "surf" the film—move through it as a datascape and explore the areas that grab you.

Bodysong brings attention to the power and vibrancy of real-life images; you have managed to make hospital and educational footage "cinematic." There's a forceful freshness and honesty to the images that you have selected.

We wanted to try and address the invisibility of certain images within "cinema,' and ask what is interesting that we've recorded with film as freshly as possible. Many people have come up to us and said they had never seen a baby being born in life or on the screen, and often they are stunned and quite emotional. Of course the same viewers watch stylized violence the whole time and barely register it.

The DVD of Bodysong has just been released in the UK. Is there something about the DVD that adds to the website and the film?

The DVD has both the film and a high-resolution version of the website on it. As well as that it has interviews with Jonny and me about the process of making the film, and a couple of earlier films I made on it.

How have audience reactions to Bodysong differed across the world?

It elicits very strong responses, probably from young adults who are very hungry to see images of the world outside the narrow confines of traditional cinema. Otherwise, the responses have been quite similar around Europe and the US. In terms of reviews, the film polarizes people. Reviews either see it as an important and significant film or [claim that] it has no business to be in the cinema at all!

Darianna Cardilli is a Los Angeles-based editor and documentary filmmaker.