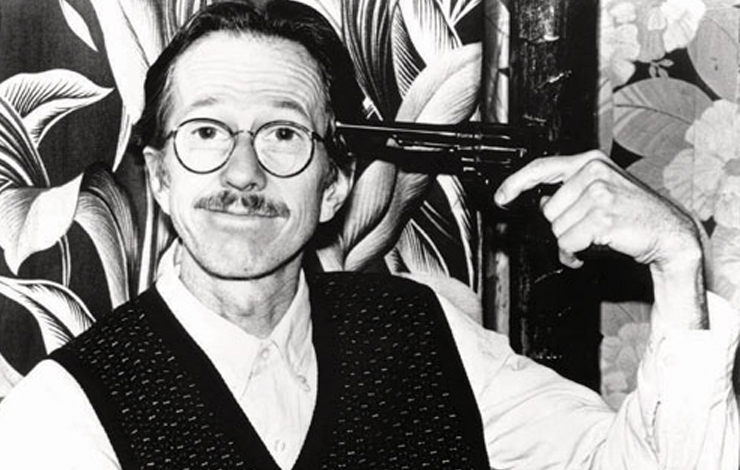

I saw Crumb, Terry Zwigoff's portrait of the artist R. Crumb, in 1994 at a packed New York Film Festival press screening where the only seat available was the carpeted stairs. From the first scene I was mesmerized.

On the surface, the story is so simple: The artist, in the autumn of his career, is leaving the safety of his secluded Northern California nest to start over in France. Zwigoff uses this as an opportunity to reflect on Crumb's life. As Crumb puts it in the film, "France isn't perfect, or anything, but it's just slightly less evil than the United States."

Yet somehow through this beautifully simple premise, we get so many themes, issues and subtexts--from artistry and fame to debunking the far-out '60s and '70s; from a meds-and-all portrait of a real American family, to looking at love in all its beauty, heartbreak and healing. And still, thanks to Zwigoff's shrewd combination of control and surrender, the film never feels like it's trying to say too much.

When I watch this film, I feel as giddy as Crumb getting a piggyback from a sturdy-legged woman. But how can I feel giddy about a film that has so many elements that our society considers "dark?" Probably because those elements are so real, universal, sad, hilarious, sexy and disturbing that "dark" falls short of the mark. While my family is possibly more "socially acceptable" than Crumb's, let's just say that the honest capturing of their internal and external psychological warfare is both uncomfortable and cathartic.

There are so many worthy scenes; allow me to describe two very different ones.

I love the scene where Crumb shows us photos a friend had taken of electric cables and other urban background banalities. "You can't remember these things," says Crumb. This simple scene is both timeless and timely, micro and macro, and is one of the most memorable in the film.

In another, Crumb is drawing with his 20-ish son from his first marriage. The scene is so quiet and beautiful to look at, it almost feels sweet. But there is so much going on beneath the surface: father vs. son, artist vs. artist, master vs. mentor. And to underscore the dynamic, they are both drawing the same portrait of a woman from a book about insane asylums. "You haven't learned to cheat yet, to get the desired effect that you want," Crumb says to his son. Cheating is point of view, the artist's opinion of the world. Is there any great art without it?

While there are many people to acknowledge for the success of this film, including Maryse Alberti for her elegant and egoless cinematography, Zwigoff and his editing team, led by Victor Livingston, deserve special recognition. They wrestled this beast of information into a sublime piece of art. When I first saw the film, I heard industry rumors that it was a difficult edit, "really hard to find the story," but now, having made my own films, I know how difficult it is to cut any documentary--especially one as nuanced and layered as this. As the saying goes, "If it was easy, everyone would be doing it."

My four-year-old daughter Tessa gives her own definitions to words she likes. "Cupcake," for her, is "someone who is both naughty and funny." By that definition, Crumb, its subject and its director are all wonderful cupcakes.

Scott Hamilton Kennedy's The Garden was nominated for a 2009 Academy Award for Best Documentary feature. For more information on his work, visit www.blackvalleyfilms.com.