We are excited to announce today that Carol Leifer will host the 30th Annual IDA Documentary Awards, to be held on Friday, December 5, 2014 in the Paramount Theater at Paramount Studios in Los Angeles. Carol Leifer has starred in five of her own comedy specials that have aired on HBO, Showtime and Comedy Central and has written for the Oscars® telecast seven times. She is a four-time Emmy®-award nominee for her writing on Seinfeld, The Larry Sanders Show and Saturday Night Live. She also received the prestigious Writers Guild Award for her work on the number one comedy, Modern Family. She is the author of the bestselling When You Lie About Your Age, The Terrorists Win and her latest book How To Succeed In Business Without Really Crying.

We're also pleased to reveal the exciting list of guests scheduled to present awards to some of the night's esteemed honorees. Presenting the Career Achievement Award to Robert Redford is Oscar®-winning filmmaker Barbara Kopple (Harlan County USA, American Dream). Monica Lewinsky, subject of Monica in Black and White, will present the Pioneer Award to World of Wonder's Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato. Marshall Curry, director of Point and Shoot and Street Fight, will present the Emerging Documentary Filmmaker Award--sponsored by Red Fire Films and Modern VideoFilm--to Darius Clark Monroe, director of Evolution of a Criminal. Rory Kennedy (Last Days of Vietnam, Ethel) is slated to present the Pare Lorentz Award for Andrew Hinton and Johnny Burke’s film Tashi and the Monk. Also scheduled to present is Jorja Fox (CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, Lion Ark).

See the full list of honorees and nominees, and purchase tickets

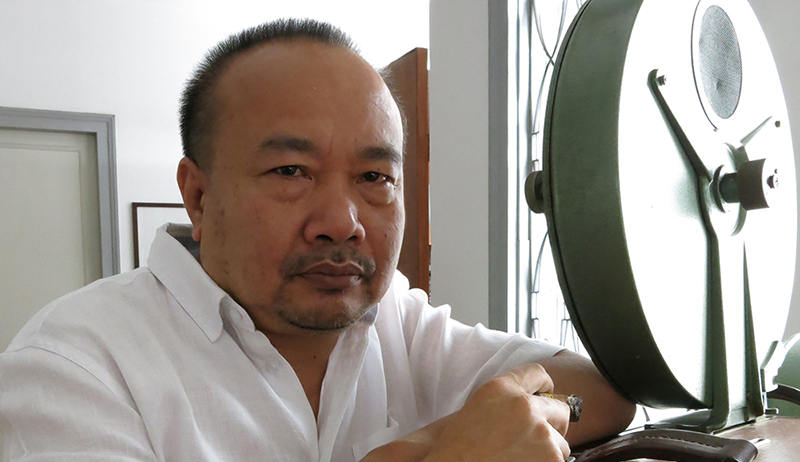

This year’s recipient of IDA’s Preservation and Scholarship Award is Cambodian director Rithy Panh, 60, whose most recent autobiographical film, The Missing Picture, won top prize in the Un Certain Regard section of the 2013 Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, as Cambodia’s submission. The Missing Picture blends clay figures, photographs and Khmer Rouge propaganda films into a devastating memoir of Panh’s family’s demise in the work camps of that murderous regime.

The Preservation and Scholarship Award goes to Panh for co-founding, along with filmmaker Ieu Pannakar, the Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center in Phnom Penh. This young institution, established in 2006, is the repository for film, television, photography and sound archives on Cambodia, drawn from around the world. Visitors can access these materials free of charge. The Center also provides filmmaking training and produces "modern audiovisual creation, filmmaking and multimedia."

A Center event, Cine Saturday, screens propaganda films made by both the Khmer Rouge and former Cambodian ruler King Norodom Sihanouk, as well as documentaries by filmmakers such as Raoul Peck (and Panh himself, of course) and fiction such as the Catherine Deneuve-starrer Indochine. This past August, the Center commemorated the centenary of Indian cinema with Bollywood classics from 1958 to 2003. Other programs include a cine club, conferences, exhibitions and mobile screenings outside of Phnom Penh. The Center also produces the Cambodian International Film Festival, which runs December 5-10.

We reached Panh via email, and he was gracious enough to take time out from his production shoot to respond to our questions.

Can you tell us about the origins of the Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center?

Rithy Panh: After the Khmer Rouge fell [in 1979], the whole country was in ruins. Generations of memory had been destroyed, and it was left to us survivors to rediscover and redefine our shared identity. Many of the tools, the tangible things and the people that would ordinarily help us do this, were no longer. Wanting to preserve what limited memory was left, Ieu Pannakar began collecting old films he found scattered across streets and cities.

Then in 1990, some friends and I discovered this collection, stored in the roof of the Cinema Department in Phnom Penh. I remember the first thing that came to my mind was noticing what poor condition all of the films were in, followed by feeling deeply sad: "Everything has been destroyed; everything has been taken from us." With the deterioration and decay of these films, I felt like our identity, our sense of belonging, would continue to diminish and die. We couldn’t let another memory be ripped away from us, so we did what we had to do to ensure the film collection’s survival. We asked Ieu Pannakar and the Cinema Department for their support, and without any film archive experience, we looked at ways to store and preserve these films while simultaneously sharing them with others.

At first, we thought we could just create a library. But as our vision and mission refined itself, we realized our goals were much bigger than that. We were not film archivists or teachers, and we had to learn from the very basics up. We needed to know about copyright, preservation, business management, community engagement, fundraising. We needed a whole range of skills in order to see our idea realized. In the beginning, many people were reluctant to invest in us. Owners of prints were afraid to hand over their films to a bunch of young Cambodians new to the game. But we continued to work at it voluntarily, doing solid days and nights. Ten years later, the Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center was realized and given to the people to explore their heritage.

What is the origin of the name Bophana?

Bophana was separated from her husband throughout the Khmer Rouge era. Imprisoned in S-21 prison, she was forced to write a "confessional" biography: who she was, whom she knew and her background. Through horrific torture and suffering, Bophana had to write her full story; she confessed she was with the CIA, although this was false. Each time she did this, she signed with the name Seda Deth. She did not know her husband was also in prison right next to her, but in signing this way, she tried to reinforce to him that she would not let the Khmer Rouge break her. They could torture her, abuse her, interrogate her—but they could not destroy her spirit or her love for him. This is a strong message for the next generation: a message of resistance in the name of love. Our spirit and the message we choose to send to the world can have a profound impact on the society. At the Bophana Center we want people to have a voice to share and exchange their message, doing so via conscious, empowering and creative channels.

Tell us about the Bophana Center’s co-founder, Ieu Pannakar.

Ieu Pannakar was one of the first Cambodian filmmakers. He worked for King Norodom Sihanouk. He made Cambodian television, was a pilot, an engineer, he built railways…a man of many skills and talents. His true passion, however, was cinema. When the Khmer Rouge fell, he helped to establish the Department of Cinema, worked for the King as a senator and continued making films. Today he shares his time between prayer and filmmaking—he is a man of many passions and much enthusiasm. He is a great mentor to me, and in those early days he supported me in developing the Bophana Center. He provided us with the building for the center, and he talked and guided me along all the way.

How did you incorporate the Khmer Rouge footage into The Missing Picture?

The footage used in this film was not singularly used by me but has been used by many directors and filmmakers both here and abroad to document the Khmer Rouge. It is a long-term goal to see this database extend to become accessible worldwide and available over the Internet for other cultures and places to learn about our past.

I think the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has it right when it lists access to information and freedom of expression as a fundamental right to every human being. Being able to learn about your roots, your culture, your identity and that of others is an essential component to any healthy society. Young people have their minds floating above themselves, buzzing within the technological world of Facebook and mobile phones. We have information overload and much of it is rubbish. We have to teach our young generations now how to distinguish the good from the bad. Many youth wouldn’t know where to start in accessing quality information and memory resources, so we have to help lead them to it.

Is there the possibility that there are "lost" Cambodian films hidden somewhere in the countryside?

I am sure of it. It is this belief that has driven my work until now. But these are not so easy to locate, and if found, are often in very poor condition, requiring high-tech equipment to restore and preserve them. One Japanese expert is now working with our team on film restorations. Many more films are no doubt scattered across the world, and any new material we acquire will only add to our memory and build upon what we know and understand of ourselves.

I aspire to find these, find them all and bring them back to life but, like everything, this takes funding. I think about our history: the US bombings, then the Khmer Rouge, then the civil war and all the lives lost, and the destruction and suffering that resulted. I think of all the expertise and knowledge that was wiped out as a consequence and how now we are struggling to rebuild; our path of prosperity and peace has been shattered.

Genocide is not only killing; it is not only deaths. It is much more than that. It is the complete destruction and deprivation of our culture and our identity. After all of this, when we look to rebuild what we have lost, we find ourselves left begging for help—as if all the responsibility and accountability have been placed on our backs alone and the past forgotten. If we don’t try to access and preserve our memory, it means the millions dead will stay only a statistic with no face, no name, no story. The dead will be nothing.

Frako Loden is adjunct lecturer in film, women's studies and ethnic studies at California State University East Bay and Diablo Valley College. She also reports on film festivals for Fandor.

Brand, niche, Klout Score, impressions, presence, following: those were the buzzwords bandied about by experts at the 10th annual Film Independent Forum held October 24-26 at the DGA in Los Angeles. "Break Through the Noise" was the title of the conference, and to do just that, upon registration each attendee was handed a heavy book replete with professional contacts, foundations and a compendium of case studies compiled from previous forums.

Despite an opening night narrative film (Nightcrawler), the last day of the Forum consisted of several panels and lectures geared to documentary filmmakers.

The day started with a memorable and highly amusing keynote speech delivered by Tim League, founder and CEO of Drafthouse Films and Fantastic Fest. Prefacing his lecture with the cautionary words that nearly "all distributors are nearly criminal in their relationship with filmmakers" and "it's now a wild, wild west time in distribution" with mode and methods constantly changing, League strongly emphasized the importance of beginning with the end in mind. "Figure out who your audience is before you make your movie," he urged, as only a small fraction of one percent of the 50,000 movies made every year make any money.

League also emphasized branding: "Think of yourself as a brand. Work hard and constantly to develop your brand and your community. It will come in very handy when you need to raise money and distribute. Try to engage in social media on lots of different platforms. Have a Twitter campaign; it's a great funnel to gain a social media presence. Exploit any opportunity to gain social media followers."

Building up a Klout Score (an aggregate of Facebook and Twitter followers) was of paramount importance to League. This can be enhanced by posting strong content and encouraging real conversations. League highlighted the unusual promotion of the documentary A Band Called Death, which entailed a Tumblr page, created three months prior to the release of the film and which featured 150 unknown "dad bands," including photos, MP3s and essays by their sons and daughters. This strategy generated lots of editorial and press interest. "We found an interesting story and created lots of sharable social media around it in a tangible way," League said. "The documentary space is unique in that you can find opportunities to do that."

Given his inside track on film distribution, League imparted very potent advice: "Get a sales agent! All distributors are borderline criminals, and if they sense weakness, unpreparedness and ignorance, they will exploit that. You run the risk of getting into something that you don't understand, and the 10 percent [for the sales agent] is worth it in terms of access, credibility and safety, because without a sales agent, odds are that you will be extremely violated."

Tim League of Drafthouse Films delivering the keynote address at the 2014 Film Indepedendent Forum. Photo: Amanda Edwards/WireImage

League also stressed the willingness to experiment and be open to new concepts, suggesting Vimeo (as a transactional space for a one-click purchase) and CreateSpace (which offers DVD burn-on-demand or Amazon Instant Video) as new methods for distribution and self-promotion. In the case of Joshua Oppenheimer's The Act of Killing, Drafthouse offered free bundles (trailer and exclusives, PDFs, calls to action) on BitTorrent, resulting in 3.5 million downloads worldwide, 51,000 impressions on iTunes, and 52,000 new email addresses. "There's an inherent value in every email address you get, as you can use them to promote the next film," League explained. "As companies are spending a lot of money to continue transacting with people in the online space, as a filmmaker you need to to keep pace with what is happening in the online industry."

League emphasized that all filmmakers, with or without a distributor, should become experts at PR and marketing. He stressed the importance of early, active and constant audience engagement, which can require thousands of hours of works over years. In the case of Indie Game: The Movie, in a period of two years, filmmakers James Swirsky and Lisanne Pajot generated over 10,000 emails, 14,000 Tweets, 184 blog posts and 51 Kickstarter updates.

"All distributors, myself included, are just making it up as we go along," League concluded. "This is a rapidly changing landscape; young people are engaging in content very differently than old geezers like myself."

At the lunch that followed the keynote address, attendees engaged in informal roundtable chats with experts. John Cardellino of the Sundance Documentary Film Program (DFP) was there to inspire and guide prospective grant applicants to the Sundance Documentary Fund. The DFP has a biannual global open call for submissions of grant proposals. The grants range between $20,000-$50,000 and are awarded to films at different stages: development, production and post-production.

Luncheon at the Film Independent Fourm. Photo: Amanda Edwards/Wire Image

Cardellino conceded, "You can send in just an idea, and in the past we have granted films in early development, but competition is stiff. We get over 800 applicants per round [Spring and Fall], of which only 20 to 30 get grants."

The criteria for assessing a submission are story, access to story, the storyteller and the team. "In your director's statement, explain why this story is so important and why you should be the storyteller," Cardellino explained. "The funder will have questions about the characters, so explain the nuts and bolts of your story. Consider what is going to best represent you as an artist and why you are the best person to tell the story."

The visual sample of the director's previous work is very important, but the DFP does consider filmmakers at any stage of their career, having given grants to both first-time directors and established filmmakers such as Frederick Wiseman. In fact, Cardellino emphasized, "Don't be afraid to say that this will be your first feature-length documentary; people like to identify new talent. We are constantly on the lookout for new independent voices."

Perhaps the biggest mistake applicants make is over-sharing the work sample. "Do not send in a long assembly," Cardellino recommended.

Though highly competitive, being awarded a grant does not mean a guaranteed entry into the Sundance Film Festival. "Last year 40 grantees applied but only 12 of those got into the festival," Cardellino said. "We respect the integrity of programming of the festival, which is separate from the film program."

However, grantees are eligible for a number of artistic support opportunities and mentorship programs. Most coveted among these are invitations to the prestigious Sundance Creative Labs, which, for documentaries, include Edit and Story and Creative Producing (held at the Sundance Resort), as well as Music and Sound Design (held at Skywalker Sound). At the labs, filmmakers have direct access to a "documentary A-team," comprised of producers, directors, editors and composers, to assist them in shaping and finishing their film.

Given the rather daunting statistics of one in 40 hopefuls obtaining a grant, the DFP does encourage repeat applicants. "We strongly recommend that you apply again," Cardellino advises. "We do tell filmmakers to explore their idea further and to keep us in mind in the future. The average documentary takes three to five years of your life to make. Don't think of it as a capital investment but as an artistic investment. The reality is that when it comes to any documentary success story, it is not just supported by the Sundance Documentary Program alone. Filmmakers are getting used to the practice of cobbling together grants. It's a very trying process, but don't give up. "

After lunch, distribution guru Peter Broderick, president of Paradigm Consulting, gave an enlightening speech entitled "Empowered by Your Audience." The lessons imparted were backed with concrete examples of successful strategies employed by a variety of films.

Peter Broderick addressing the audience at the Film Indepdendent Forum. Photo: Araya Diaz/Wire Image

"Start thinking about your audience the next time you think about your next film" he urged the attendees. "Create great content. Have a great online presence. Have a huge Facebook presence."

That said, Broderick stressed that you "need names and email addresses, not just ‘likes' on Facebook. Start building an audience early, using your mailing list and your team's mailing list. Keep those people engaged with weekly newsletters."

Even more important, "Make it personal when you are trying to build your audience." Broderick continued. "People buy things from people. Don't have everything on your website in third-person ‘press releasese.' Write in the first person. Don't have info@_____ for your contact email. People want to write to a name. What can you send people along the way that they actually want [such as stills or music], rather than just an update on your film?"

This audience can also be used purposefully for regular feedback on scenes, teasers, trailers, music and, ultimately, test screenings. The team behind Burn reached out to their audience during production, using their email list as a test-screening audience.

"I find most filmmakers don't do enough test screenings, and I strongly recommend them," Broderick added, citing that Lee Fulkerson, the director behind Forks Over Knives, did over 20 test screenings of his film.

"Do not underestimate the power of free," Broderick added. "When Stacy Peralta wanted to build an audience for Bones Brigade, he offered free downloads of a previous film and within a few weeks he had 46,000 email addresses." Similarly, the team behind Food Matters made their second film, Hungry for Change, available for free for 10 days. Over 450,000 people watched it for free and in those two weeks they sold $10 million in DVDs and recipe books. At present, the filmmakers' mailing list exceeds 780,000.

Broderick also revealed that "the most important reason to do to crowd-funding is to build your audience for your film. Fundraising is secondary."

Broderick also encouraged his audience to "Make a brand for yourself! The audience is not subject-specific." Gary Hustwit (director of the design trilogy Helvetica, Objectified, Urbanized) made novel use of his fans: Finding himself stranded in Amsterdam with maxed-out credit cards, he relied on his extensive Twitter following to sell unique items, and in an hour he earned enough to pay for a hotel room. The auteur approach was also used successfully by Stacy Peralta in building support for Bones Brigade, selling one-of-a-kind skate boards, surf boards and T shirts on his website. "It's not just the quantity of your fans but the quality that counts," Broderick maintained. "Try to cultivate ardent supporters."

Broderick concluded by instilling a final piece of advice: "You need to think about your goals: maximizing revenue, maximizing your audience and increasing social impact."

Clearly, for a documentary to be successful nowadays, you cannot just rely on making an engaging film, but also have to exploit social media to its fullest potential. And you need to devote yourself to constantly marketing your film, from pre-production until well after its completion.

Darianna Cardilli is a Los Angeles-based documentary filmmaker and editor. Her work has aired on Bravo, A&E, AMC and the History Channel. Her articles have been published in Documentary, Dox and VivilCinema. She can be reached through www.darianna.com.

Orson Welles' Faux Doc 'F for Fake' Gets Blu-ray Release

By Josh Slates

F for Fake, the last feature-length film that Orson Welles would complete before his death in 1985, is a rollicking and mischievous ode to fakery, trickery and deception that receives a brand new Blu-ray release on October 21 courtesy of The Criterion Collection. This one-of-a-kind collaboration between Welles and French documentary filmmaker Francois Reichenbach is equal parts cinéma vérité and trompe l'oeil, but certain to delight and confound viewers in equal measure.

Today, F for Fake could be classified as a melange of nonfiction content and deliberately misleading "mockumentary" vignettes that combine to toy with viewer expectations within the framework of a visual essay. However, at the time of its original release, audiences had never really seen anything like it, and would have been at a loss to easily summarize the experience or explain its unique structure. Indeed, as film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum observes in an essay that accompanies the Criterion release, noted film historian Lotte Eisner emerged flummoxed from an advance preview screening in 1973 and declared, "It isn't even a film."

The origins of this unusual exercise in misdirection and cinematic sleight of hand were forged in a fateful meeting between Welles and Reichenbach, who had approached the mythic auteur about providing narration for existing documentary footage of infamous art forger Elmyr de Hory. A seasoned painter himself and a contemporary of Modigliani and Matisse, de Hory was living in Ibiza at the time and basking in a glow of notoriety that arrived with the publication of a biography titled Fake! in 1969. In both the book and in Reichenbach's footage, author Clifford Irving offers no shortage of amusing anecdotes detailing de Hory's long criminal history of fakery. And yet Irving would in turn be exposed as a fake himself after swindling McGraw-Hill out of a six-figure advance for an autobiography of Howard Hughes that was purported to be authored in the reclusive tycoon's handwriting. Although forensic experts had declared the autobiography to be genuine, it came to light that the manuscript was in fact manufactured by several of Irving's artist and writer acquaintances and based on previously published examples of Hughes' handwriting.

Art forger Elmyr de Hory, featured in Orson Welles' F for Fake. Courtesy of The Criterion Collection

After Reichenbach treated Welles to a private work-in-progress screening of the project, the auteur instead proposed to incorporate the footage into a larger, more expansive pastiche on the subject of phonies, forgers and fakes. The subject of manipulated reality is course perfect fodder for Welles, who entered the public consciousness by pulling the wool over the ears of a nation of radio listeners with his dramatization of H.G. Wells' The War of the Worlds.

Incorporating new footage directed by Welles and co-written by his longtime collaborator Oja Kodar, the filmmaker revels in his reputation as a "charlatan" and positions himself as a comrade of Reichenbach's deceitful subjects. He is still the youthful magician who amazes passersby at the Gare du Austerlitz with flights of illusory fancy, having lost none of his propensity for showmanship and spectacle.

Welles' fascination with the obfuscation of truth is naturally front and center in this very personal film, although F for Fake also provides viewers with a wonderful document of his later years. The filmmaker's obsessions and infamous epicurean enthusiasms are on full display, especially in one memorable set piece that unfolds at the Parisian restaurant La Méditerranée, well known as his home away from home during a self-imposed exile in Europe during the '60s and '70s.

Orson Welles in front of La Mediterranee. Courtesy of The Criterion Collection

Welles really outdoes himself with the highly inspired montage of F for Fake, which is bursting at the seams with rapid-fire edits, ironic optical effects and freeze frames that lend dramatic import to the proceedings. To wit, much of the movie unfolds in the editing room itself, with cinematographer Gary Graver observing Welles at work on a Moviola editing machine as the movie segues out of Reichenbach's 16mm workprint and match cuts to a gorgeous 35mm blow-up of the same material. On a commentary track that is included on the Criterion release, Graver observes many instances of edits that are "so quick that the negative cutters couldn't find edge numbers." In keeping with the overriding theme of sleight of hand, the title of the film never actually appears on screen. Instead, Welles is seen in silhouette scrawling a question mark upon a still frame of stock footage from, appropriately enough, the 1956 science-fiction cheapie Earth vs the Flying Saucers.

From a technical standpoint, Criterion's new release of F for Fake shines in every way, with a new high-definition telecine transfer of an archival 35mm interpositive that also sports an uncompressed monaural soundtrack, both of which serve as considerable upgrades from the already excellent 2005 DVD edition. This new release, thankfully, retains all of the supplements and extras from the original DVD edition, including the aforementioned audio commentary in which both Graver and Kodar generously share their own wistful recollections of Welles and his freewheeling production process.

The multitude of special features helps bring the supporting players into clearer focus. In the feature-length 1995 documentary Orson Welles: The One-Man Band, Kodor serves as a guide to the many unfinished projects that Welles dabbled with during his final years. Most illuminating is the inclusion of some edited footage from the unfinished narrative feature The Other Side of the Wind, featuring John Huston and Welles stalwart Peter Bogdanovich. Also included is the 1997 documentary featurette Almost True: The Noble Art of Forgery, which is a more by-the-numbers study of Elmyr de Hory and the release of his forgeries into galleries and upon museum walls around the world, and which provides a more nuanced portrait of its subject as both an unrepentant grifter and a charismatic bon vivant. Rounding out the special features is a nine-minute theatrical trailer for F for Fake, which is comprised of an assortment of original footage that Welles created specifically for distributor Seven Gables but was never used, as well as a 60 Minutes segment from 2000 featuring Clifford Irving and Mike Wallace recounting a 1972 interview in which the author refuted accusations of fraud related to his soon-to-be-published autobiography of Howard Hughes.

All in all, The Criterion Collection delivers another smashing release with its new Blu-ray edition of F for Fake, which provides both a fascinating study in the malleability of the nonfiction form as well as a boisterous portrait of Welles in his sunset years.

Courtesy of The Criterion Collection

Josh Slates is an independent producer and director based in Baltimore. He is also a film critic and field producer for The Signal, a weekly arts and culture program produced by WYPR Radio.

Filmmaker Jesse Moss has a long history of making subtle but challenging documentaries. His latest work, The Overnighters, follows a pastor in North Dakota who struggles to shelter an influx of people who have shown up in the state from all over America, desperate for work. Pastor Jay Reinke's struggles are compounded by his efforts to reconcile the principles of his faith ("Love Thy Neighbor") with the objections of the townspeople to his taking in some Overnighters with sketchy pasts—and by his own personal demons and discretions. Prior to the film's world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, we talked about this complex tale of faith, redemption, community and betrayal.

The Overnighters earned a Special Jury Prize for Intuitive Filmmaking at Sundance, then went on to win the Grand Jury Prize at the Miami International Film Festival, the Inspiration Award at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival and the Golden Gate Award for Best Feature Documentary at the San Francisco International Film Festival.

I followed up with Moss in June to talk about his journey with the film, which opens October 10 through Drafthouse Films.

Documentary: How did you come to make this film?

Jesse Moss: I originally went up to North Dakota for a television network. That project fizzled, but the place astounded me. The scale of transformation in the small town of Williston was extraordinary, and I felt like I was touching a live wire that arcs back through American history to mythic American boomtowns like Deadwood and Dodge City. When I met Pastor Jay and some of the men sleeping in the church, I knew I had to start filming, but had no idea where the story would take me.

How long was the production process? How many trips did you take to North Dakota?

I made 16 trips to Williston over two years. Each trip was between five and eight days, so roughly 80 days of production. For the first six months of production, I slept in Pastor Jay's Church, largely out of necessity—all the hotel rooms in town were booked solid by oil companies. I worked alone in the field, as producer, director, camera and sound recordist, which accounts for the intimacy of the film.

From a filmmaker's perspective, did you have a sense of where the film was going as you shot, or did it start to really come together as you went through the footage?

I had some sense that a story was emerging around Pastor Jay's dedication to helping the Overnighters and the emerging conflict with his congregation, his neighbors and the local newspaper about that decision. But I spent a lot of time filming secondary characters, some of whom are not included in the final film. There were a lot of characters to juggle, and finding the right balance—and allowing Pastor Jay's story to drive the film forward—required a lot of experimentation in the edit room.

I will say that hugely important themes emerged only very late in the edit, and that scenes and characters I was sure would be in the final film were dropped. Credit goes to my editor Jeff Gilbert, who brings a sharp eye for story and dramatic construction, a real rigor to his method, and a willingness to tolerate my wild and ornery impulses.

Like any doc, you start to get close to the characters, and you want to treat them with respect. At a certain point you must have struggled with how to handle the main characters' comfort with the camera and how that clashed with other people's comfort. The scene where the pastor talks to his wife about his indiscretions, for example, must have been a real challenge.

I spent a long time building my relationship with Pastor Jay, his family and the other men in the film. Working alone helps in this regard. So there was a strong foundation when the story took unexpected and painful turns.

Talk about the experience of showing the film to, and with, Pastor Jay. How has the film affected him and his family? How about any other characters in the film? How do you as a documentary filmmaker deal with that line of balancing the needs of your characters with that of the film?

Jay and I watched the film together at my house in San Francisco. I think that the film was quite scary to him in abstraction, but once he was able to watch it, his concerns subsided. He told me he could recognize that the movie has a very powerful and positive message. He did have some comments, which he conveyed, and that we discussed at length.

Jay came to Sundance for the film's premiere, with the blessing of his wife. He's a tremendously brave person. I told him that I thought the story would resonate strongly with audiences, and that they would embrace and respect him, but I couldn't be certain. It was a real leap of faith. And Jay was at a very low point.

But he came, and it was an electrifying response—terrifying for both of us, but intensely moving. And for him, it was affirming. He had many conversations with audiences—I think he participated in five screenings—and many one-on-one conversations. He was recognized on the streets of Park City, and on the shuttle bus. And it was validating for both of us when the reviews arrived.

Jay's family members have each come to the film in their own way, privately, and subsequently in more public ways. His daughter Mary attended a public screening in Minneapolis, and his son Eric came to our screening in New York, at the Tribeca Film Festival. That was very important for Jay. At the Q&A, Eric said that he understands his father better now after watching the movie. It was emotional. Eric is as brave as his father.

Navigating through the intense turbulence of Jay's life and the dramatic turns of the story has been the biggest challenge of my filmmaking career. We hit some rough patches—but Jay trusted me, and I worked hard to return that trust by making a compassionate and honest film. Jay has faith. He believes the best in people. For that, I'm lucky and grateful.

I think the central tension of documentary is that very line you refer to—that balance between our obligations to our subjects and our story. You can side-step those questions, depending on your formal approach. For me, it's a shifting line, one that is constantly being drawn and re-drawn as you make the film and your relationships evolve. I don't pull any punches, but it's always been important to have my subject participate in the film's public life. I think the integrity of that relationship is written into a film, on screen, and audiences recognize it—and your subjects recognize it too.

I'm hopeful that Keegan can attend the film's New York premiere. Unfortunately, I've lost contact with two men in the film: Michael and Alan.

Have you shown the film in North Dakota, and if so, what was the response there?

Jay and I have discussed screening the film in Williston, followed by a conversation with community leaders, members of the church, the newspaper and local residents. He's enthusiastic about the idea. We're in the initial planning stages now.

The critical and audience responses have been extremely positive. Talk about your distribution plans.

We've had an incredible festival experience and the response has been very positive. Critics and audiences have really embraced the film's moral complexity. It's also an emotional experience for viewers and a film that people think about, talk about and argue about for days after they see it—so I've been told. Drafthouse Films, which is a truly bold and visionary distributor, will be releasing the film theatrically in the fall, and they are building an engagement campaign to leverage the conversation we believe this movie can spark.

This is a story not just about Williston but about America today—about the increasingly stratified society we live in, about affordable housing and the homeless in our own communities, and about the choices we all face when we consider what it truly means to "love thy neighbor."

What does your next project look like?

I'm very much focused on The Overnighters right now, but I'm developing some documentary ideas and finishing a feature screenplay that's based on a true story.

Michael Galinsky is a filmmaker and photographer. His latest film, Who Took Johnny, co-directed by Suki Hawley and David Bellinson, is on the festival circuit.

It's no secret that women make up a large majority of the documentary world's executive positions. Cara Mertes, director of the Ford Foundation's JustFilms; Tabitha Jackson, director of the Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program; Diane Weyermann, executive vice president, documentary films at Participant Media; Molly Thompson, senior vice president of A&E IndieFilms; and Sheila Nevins, president of HBO Documentary Films are just of a few of the nonfiction genre's gatekeepers.

But for most women, show business and almost all other career-oriented disciplines are uphill battles. But while that climb has become less difficult in documentary, it's still a very tricky endeavor to reach the peak, which is why Dyllan McGee, executive producer at Kunhardt McGee Productions, founded Makers.

A multi-platform initiative developed by AOL that aims to be the largest collection of women trailblazer stories ever assembled, and includes a growing collection of over 250 original interviews online, Makers is about "bringing to life new and unforgettable stories, preserving those stories and letting every household in America have access to them."

Makers.com launched in 2012 with the stories of 100 groundbreaking women. In 2013, Makers premiered the three-hour documentary Makers: Women Who Made America, telling the story of the modern American women's movement for the first time on television. The film aired on PBS to 4.3 million viewers.

On September 30, a series of six new one-hour Makers documentaries is scheduled to premiere on PBS every Tuesday for six consecutive weeks. The hour-long specials will tell the stories of women in six spheres of influence: comedy, Hollywood, space, business, politics and war.

The Makers presentation at the Television Critics Associaiton Press Tour, left to right: Dyllan McGee, executive producer; screenwriter Linda Woolverton, from Women in Hollywood; for US Congresswomen Pat Schroeder,from Women in Politics; and filmmaker Ava DuVernay, from Women in Holllywood. Photo: Rahoul Ghose/PBS

"Makers is not just a media project, it's a movement," explains McGee, series executive producer. "The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media reports that since 1946, gender inequality on screen has remained largely unchanged and unchecked. Our goal at Makers is to help change that statistic."

Nine years ago, McGee had no idea that she was going to build a multi-media empire. Back then, she just wanted to tell the story of Gloria Steinem, so she approached the feminist icon, only to get rejected. As McGee recalls, "In her egoless way, [Steinhem] said, ‘You can't tell the story of the women's movement through the story of one person. There's a much bigger story to be told.'"

The rejection initially felt like a failure to McGee because she figured that the women's movement was a story that had surely been told "a million times" in nonfiction form. She was wrong. Instead there were hundreds of important stories that had never hit the screen, let alone been taped. McGee did eventually make a film about Steinhem—Gloria: In Her Own Words, which aired on HBO in the summer of 2011 and earned an Emmy nomination. "Gloria inspired me to do more than just one film, and now I have made it my passion to capture and preserve the story of women both known and unknown," McGee states.

In order to do that, McGee decided to flip the documentary model on its head by kicking things off online. She and her team posted individual stories on the Web, with the goal to then take the best material and create a documentary from the bottom up.

"When this project started almost 10 years ago now, video was just kicking off on the Web, and I knew it was going to change the documentary film medium," McGee says. "The way people consume media now is more and more in short form, but I'm an old-fashioned documentary filmmaker in that I believe in the long form. That said, I think there is a place for both the long and short form. What was important for this project was to reach a young demographic that isn't necessarily connected with the idea of how important it is for women to keep advancing."

In order to reach that young demographic, McGee knew that she had to create something that was short-form. Makers.com launched two years ago, with the stories of 100 groundbreaking women including Hillary Clinton, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Oprah Winfrey. Today the site features over 2,500 videos and more than 250 women, with new short films/interviews launching each week on "Makers Monday."

When it came time for the latest documentary series, McGee said that it was "very hard to narrow it down to six one-hour episodes. The first documentary was about the women's movement. Now we are looking at what's been the ripple effect of the women's movement. Where are we in each of these industries? At the end of the day, it's about picking really good stories. Sometimes there's a really interesting topic, but there are no stories in it."

Each documentary examines the impact of the women's movement on six fields once largely closed to women. Veteran documentary directors Heidi Ewing, Rachel Grady, Linda Goldstein Knowlton, Grace Lee and Jamila Wignot direct all but one of the films. Michael Epstein serves as the sole male director, while all six episodes are narrated by women, including Julia Roberts, Leslie Mann and Jodie Foster.

"Dyllan was very persistent and really courted Rachel and me," says Ewing, who directed and produced Makers: Women in Comedy and Makers: Women in War with Grady. "Initially we were concerned with finding an original angle because, as a filmmaker, you want to have your own approach and make it as original as possible."

When it came to Women in Comedy, Ewing explains that she wasn't looking to grapple with gender inequality or for subjects to "gripe over and complain about lack of opportunity. We really just wanted to understand what it's like to stand alone on that stage with a mic. It's such a powerful position. All the women [we spoke to] had to confront that there is something very male about standing on stage and talking at people."

Comedians including Chelsea Handler, Mo'Nique, Sarah Silverman, Ellen DeGeneres, Jane Lynch and Kathy Griffin participated in the documentary. But Ewing admits that Joan Rivers made her the most nervous. "None of these women suffer fools," Ewing says. "So we really went into each interview prepared. But that said, I was still terrified to speak to Joan. Not only was it hard to get her to sit with us, but she's a force to be reckoned with. When we finally sat down [to do the interview], the first thing I said was, ‘By the way, I'm not going to ask you about the [losing your friendship with] Johnny Carson episode.' I think she appreciated that."

Heidi Ewing (left) interviews Joan Rivers for Women in Comedy. Courtesy of PBS/MAKERS

Epstein, who directed Makers: Women in Space, appreciated being the sole male helmer on the project. "I see myself first and foremost as a storyteller, and the women's movement is as much my story as an American as anybody else's," Epstein says. "It has had a profoundly positive influence on my life. So I never felt out of place as the only male director on the series. It was remarkably collaborative group of filmmakers." That said, Epstein admits that Makers is "unequivocally Dyllan's baby and vision," which presents its own challenges. "You need to find your own voice inside what is so clearly someone else's creation," explains Epstein. "For me, it's about finding the story, a story that excites me and one you think can be well told. I was able to find that with Dyllan. She gave me freedom to tell a story in my own voice."

NASA astronaut Mae Jemison, who appears in Michael Epstein's Women in Space. Courtesy of PBS/MAKERS

McGee foresees working with many more female as well as male directors on Makers. "The dream is that we can create an ongoing series," McGee says. "My goal is to make sure that all women's stories are told. So we have a long road ahead of us to make sure that that happens."

Addie Morfoot writes about the entertainment industry for Daily Variety, The Wall Street Journal and Adweek. She has also written for The New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and Marie Claire. She holds an MFA in creative writing from The New School.

Peruvian Doc Showcase Salutes a Master

Finding one's place anywhere, but perhaps especially in New York, is a challenging thing. I pondered this as I stood in a thick line straining to gain entrance to the standing-room-only opening screening of the New York Peruvian Film Showcase, taking place at the Instituto Cervantes in midtown Manhattan on September 16. For one thing, turning to a Spanish-run institution's New York outpost, whose mission is nonetheless an important one to provide a home and showcase for Spanish-language culture internationally, always adds a curious post-colonial questioning to things. For another, although Latin American film has been flourishing in recent years, Peru is not the filmic powerhouse of, say, Mexico or Argentina, and yet it has increasingly become a dynamic, richly inventive source of cinematic acclaim, its output more modest yet at the same time, arguably packing major impact. And finally, most germane to this audience, perhaps, the emphasis on Peruvian film leans toward the narrative, rather than documentary. With all this in mind, it was perfectly apt that the opening night of the festival paid tribute to the late Peruvian-American documentarian Roberto Guerra, whose output was unduly cut short last January by pancreatic cancer, but who so brilliantly "lived the questions," to paraphrase Rilke.

Guerra's body of work is a continual examination of the creative process, of the tensions and passions in life that fuel art and vice versa, of the collaborative process, and of identity and an individual's quest to sculpt and forge it beyond whatever happenstance of birth may have initially shaped them. Showcase Director Lorry Salcedo Mitrani's Roberto Guerra, a Life, which screened at the tribute, aptly examines the Peruvian-American's trajectory, interviewing Guerra's brother, Humberto, and wife and filmmaking partner, Kathy Brew, and weaving throughout excerpts from Guerra's films alongside photos that capture Guerra's life in New York and growing up in Peru. An engineer by training, Guerra's inquisitive nature and love of the energy of the present moment turned him to film.

Guerra's initiation into the world of cinema in the 1960s began at a significant moment of change in Peru, when director Armando Robles Godoy was among the first Peruvian filmmakers to receive international recognition. Although working in narrative, Robles was freely experimental in his approach, and was influenced by European art cinema while clearly also owing a significant debt to the tradition of documentary filmmaking in Peru known as the Cuzco School. The documentaries of the Cuzco School explored indigenous themes and reflected Peruvian culture's pre-Columbian roots, and ultimately engaged issues of social justice as in much of what would become the New Latin American Cinema movement. Godoy was an advocate for the training of a new generation of Peruvian filmmakers, and as such, Guerra worked with him on his 1966 film, En la selva no hay estrellas (In the Jungle There Are No Stars). But as a budding artist, Guerra was equally captivated by influences from abroad, and would become drawn to cinema vérité, and the exploration of the artistic life abroad, ultimately leading to a lifelong career and investigation of the creative process through documentary.

From Armando Robles Godoy's En la selva no hay estralleas (In the Jungle There Are No Stars)

Throughout Guerra's examination of the artistic process, he would almost unfailingly hone in on the collaborative nature of much artmaking. Collaboration was certainly reflected in his own film production partnerships, which were truly all-encompassing—of art, life and love. He began his own documentary career with his first wife, Eila Hershon, who succumbed to cancer, and later flourished artistically upon meeting and collaborating with Brew.

Initially, Guerra's artistic endeavors, coupled with Hershon's background as a painter, led them to explore art on film, focusing broadly on the creative process in the lives of artists in all media, running the gamut from painters Oscar Kokoschka and Frieda Kahlo, graphic designers such as Milton Glaser and Massimo and Lella Vignelli, and fashion designers Coco Chanel and Karl Lagerfeld. Unlike Guerra's later work, these earlier films were for the most part more conventionally structured, perhaps due to their nature as broadcast commissions. And yet they had an insistent, slightly subversive curiosity and questioning of themes that would recur throughout Guerra's career and find full, freer expression in his later work. Issues of feminism and the creative process, as read through the lens of a feminine, fertile spirit as well as the constraints and subversive upending of popular fashion, are first seen in the explorations of Chanel and Kahlo. Equally, the artist as outsider carefully crafting a unique, public identity as part of the creative process is seen throughout the work: Lagerfeld commenting on his own changing image and output throughout the years; archival footage of, and statements from, Chanel; and Glaser's own appraisal of his development as an artist.

In Guerra's later documentaries, his lens would increasingly focus on the collaborative nature of artmaking, discarding the romanticized notion of the artist alone in the studio. This perhaps aptly reflected his partnership with Brew, whose inquisitive spirit and media-arts expertise matched his and embodied the notion of a "great dyad" (as put forth by essayist Joshua Wolf Shenk in his recent book Power of Twos: Finding the Essence of Innovation in Creative Pairs). Guerra and Brew's most recent work, Design Is One: Lella and Massimo Vignelli, returns to the Vignellis as one of Guerra's early subjects, and garnered much acclaim on festival and theatrical runs. It is a fascinating look at the 50-year dynamic partnership of the Italian designers, who are responsible for so much that makes up our daily lives, with their powerful design and branding influence on everything ranging from furniture to logos to maps and far beyond. Guerra and Brew's soon-to-be-completed documentary on Seward Johnson explores the very definition of art. It doesn't shy away from the hard questions or easy glorification of artists, as they examined a populist artist who works in realistic, life-size sculptures. The filmmakers ask hard questions—of the arts community, of ourselves as audiences-about the very nature of what art is and who gets a shot at experiencing, defining and legitimizing it. In these documentaries, a loose style of observation, especially in artistic production, gives the artists ample time to speak for their own process, and allows plenty of other voices to weigh in, amplifying the fact that art does not exist, nor is it created, in a vacuum. It lives and breathes and is jostled by daily life in these documentaries, and ultimately flourishes there.

From Kathy Brew and Roberto Guerra's Design Is One: Lella and Massimo Vignelli, a First Run Features release. Photo: John Madere.

It is also through Brew that Guerra, who left Peru as a young man, was ultimately persuaded to return in 2000 to examine his roots and explore Peruvian subjects. In several works-in-progress that were excerpted in Roberto Guerra, a Life, one sees promising, compelling explorations of artists working in Peru and of topical issues at play in the country. Beauty Behind Bars attests to the effects of the drug trade in Peru, as convicted female drug smugglers compete in a beauty pageant for convicts only. While the film doesn't shy away from humor and the absurdity of the premise, it also attests to Guerra's ongoing exploration of female self-determination and political questions about international drug trafficking. Other works-in-progress by Guerra focus on the terrorism that devastated Peru throughout the '80s and '90s and the creation of an artistic, public art project responding to it; and on an artist whose work reflects the significant Peruvian concept of Pachamama (an indigenous conception of Mother Earth) and recognizes the power of a feminine spirit in creative production.

The late Roberto Guerra shooting his and Kathy Brew's documentary on the artist Seward Johnson. Courtesy of Kathy Brew

And so we look to Brew to continue Guerra's legacy as we eagerly await the completion of these future films. Additionally, Brew, in partnership with UnionDocs, is establishing The Roberto Guerra Documentary Award to honor Guerra's legacy in the field. It will be an annual prize given to a New York-based documentary filmmaker originally from a Latin American country.

Those of us who knew Guerra recall his wide and intensely curious owl-eyes, through frames like the focusing rings of a camera, watching, guiding, but mostly encouraging us to continue in the dynamic exploration of life in and through film, and the power of the collaborative, artistic spirit to endure.

Maria-Christina Villaseñor is a writer and independent curator based in New York. She writes frequently on Latin American film as well as on .film and video installation art, and is the author of William Kentridge: Black Box/Chambre Noire.

You have to be doing something awfully well for a lot of years to be known by your acronym. TIFF, or the Toronto International Film Festival , certainly qualifies. It has become the first must-attend event of the fall season for most US, European and, increasingly, Asian film professionals.

This year, TIFF drew over 5,000 industry delegates, a record breaker for the festival, and among them were 1,900 buyers. On the festival's final day, it was announced that over 35 films had been sold internationally, including such docs as National Gallery, Frederick Wiseman's incisive look at Britain's prestigious art museum; Tales of a Grim Sleeper, Nick Broomfield's dark study of a Los Angeles serial killer; The Look of Silence, Joshua Oppenheimer's powerful follow-up to The Act of Killing; Sunshine Superman, Marah Strauch's revelatory BASE-jumping feature; and The Price We Pay, Harold Crooks' muckraking exposure of the corrupt global economy.

The documentary section of TIFF clearly benefits from the overall appeal of the festival. With huge attendance at screenings, healthy government support for both the public and industry sides of TIFF and increasing global coverage of the festival, it's no wonder that just about anyone making a feature documentary targets Toronto in September as a great time to premiere their film.

As always, the selection of documentaries was top-notch. Besides the five films already cited, TIFF Docs included a duo centering on climate change, The Yes Men Are Revolting and Merchants of Doubt; a diverse quartet on the war zone that is the Middle East—This is My Land, The Wanted 18, Silvered Water, Syria Self Portrait and Iraqi Odyssey; two very different looks into Africa- National Diploma, the Congo-based indictment of corruption, and Beats of the Antonov, the People's Choice Documentary Award-winning study of war and music in Sudan; a pair of films set in Asia--Monsoon and I Am Here; as well as docs taking place in Canada (Trick or Treaty?), Italy (Natural Resistance), Russia (Red Army) and the US (Seymour: An Introduction).

Besides offering viewers a nice opportunity to armchair-travel around the world, nothing much held the films together. But then, film programming for festivals isn't the same as curating for a cinematheque. The philosophy of programming for an event like TIFF amounts to "find the best new films out there, and please don't repeat themes or stories in too obvious a manner." What's wonderful for someone at TIFF—or the Berlinale or Cannes or Sundance or IDFA—is that everyone wants to submit to you and your festival; no salesmanship is necessary.

Jonathan Nossiter, whose Natural Resistance combined ecological concerns about making chemical and additive free wine with a quirky set of clips from older Italian films, would surely attest that some years produce vintage grapes and excellent libations. So it is with films and it's clear that this is a good year for feature docs. The range was astonishing.

Take Sturla Gunnarsson's Monsoon, for example. It is a gloriously pictorial meditation on India, emphasizing the extreme contrasts in a land of deserts and floods, mountaintops and verdant farmland, cities teeming with humanity and villages where no one is a stranger to their neighbors. Using the immense chaos that the monsoon engenders, Gunnarsson has been able to convey some of the complexity of one of the greatest countries in the world.

Lixin Fan's I Am Here has already been released in China, where it grossed over $1 million at the box office. The film focuses on a "Chinese Idol" reality show called Super Boy, which pits ten young men against each other to deliver the greatest performance of the TV season. Millions watch Super Boy, and the contestants are hounded like true celebrities—at least for a while. Fan got to spend time with the young men, who are an appealing, almost naïve group. Contrasting upbeat, high-tempo songs with amazing production values to the quietly intense life that the boys spend training for their TV appearances, Fan is able to convey a sense of the unreality of the situation—and its potential for triumph or heartbreak.

In Merchants of Doubt, Robert Kenner follows up his controversial and very well reviewed feature doc Food, Inc. with an unsparing attack on those in the US who oppose legislation to stop climate change. Kenner is adept at structuring arguments in ways that are witty and devastating; he is a fine essayist and polemicist. Like Food, Inc., Merchants of Doubt is based on a book, this time by Naomi Oreskes and Eric M. Conway.

Kenner foregrounds Merchants of Doubt with repeated appearances of a magician, Jamy Ian Swiss, who demonstrates how tricks are created by misdirection. Kenner shows how tobacco companies used the same technique for decades to "blow smoke" over correct allegations that cigarettes are harmful to people's health.

Misdirection, the film makes clear, is being applied now to climate change. Kenner points out that the vast majority of scientists believe that climate change is happening but certain figures in US politics, bolstered by oil and gas money, are causing enough doubt in the public's mind to prevent legislation from occurring. Merchants of Doubt is a powerful indictment of gas and oil companies, the beneficiaries of the "debate" that is still happening today.

The Wanted 18 tackles another major topic—the conflict between Israeli authorities and the Palestinians. Set during the first Intifada in the late 1980s, the film relates one of those crazy documentary stories that can only work because it's true. With the Israeli occupation at its height, Palestinians in the West Bank town of Beit Sahour were bereft of dairy products. Town leaders bought 18 cows and set up a collective farm to answer a basic need-to have milk.

The Israelis tried to seize the cows, only to find that they'd disappeared into the mountains and rough terrain in the area. Countless attempts proved unsuccessful as the cows and their Palestinian farmers became masters at finding new, inaccessible spots where they could hide—leaving the milk to flow and the Israelis to become angrier and angrier. This amazing tale is recreated by Palestinian artist Amer Shomali and veteran Canadian doc director Paul Cowan, using stop-motion animation, interviews and drawings to illustrate how people can survive nearly anything if they have imagination and faith.

The strongest film I saw at TIFF was The Look of Silence, Joshua Oppenheimer's documentary about Adi, an optometrist who decides to confront the killers of Ramli, an older brother he never met but whose memory was worshipped by his parents. Like so many others, Ramli was accused of being a Communist and brutally murdered in the mid-1960s, when Indonesia destroyed its democratic left, at the behest of the US government. This documentary couldn't have been better cast: Adi is perfect as the anonymous accuser of Indonesian "heroes"—murderers who feign remorse and refuse to take any moral responsibility for their actions. When Adi's quiet, determined mien transforms into a scowl with his eyes aflame, the former death squad members get angry and threaten him with violence if he doesn't abandon his "communist" line of thinking. Few films have ever exposed the face of evil so effectively, or as aesthetically. This unofficial sequel to The Act of Killing is brilliant.

Oppenheimer was the highlight of the Doc Conference, speaking passionately and poetically about his experiences working in Indonesia. Filmmaker Astra Taylor (Zizek!) was also provocative and well spoken, offering a somewhat jaundiced view of the Internet and its power to influence democratic thought. The Conference ended with Hot Docs Forum Director Elizabeth Radshaw presenting the results of an audience survey conducted by Hot Docs. Her takeaways were clear: viewers of docs are highly educated and mainly female, and would support more documentaries if they knew where to find them.

The task ahead in Toronto is obvious: figure out how to attract a public when Hot Docs and TIFF Docs aren't in town. Easier said than done.

Based in Toronto, Marc Glassman is editor of Point of View magazine and Montage magazine.

Filmmaker and photographer Timothy Greenfield-Sanders may be best known for his extraordinary, large-format portraits of everyone from world leaders to artists, actors and underground icons, but it was his attendance at the AFI's Conservatory film program in the 1970s that inadvertently launched his storied career in portraiture and temporarily waylaid his career as a director. His love of film never waned, though, and in 1998 he returned to the medium with the Grammy Award-winning documentary Lou Reed: Rock and Roll Heart.

Eight feature documentaries (including the acclaimed The Black List) later, Greenfield-Sanders offers The Boomer List. Premiering September 23 as part of PBS' American Masters series, the film features 19 personalities, each representing the rapid cultural, social, political and technological shifts of the baby boom years of 1946 to 1964.

American Masters executive producer Michael Kantor (left) with filmmaker/phorographer Timothy Greenfield-Sanders. Courtesy of (c) Greenfield-Sanders Studio

Greenfield-Sanders spoke with Documentary by phone from his home in New York.

Documentary:Why did you choose to do The Boomer List now?

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders: I felt it was the right moment. I love anniversaries of things, and this year is the 50th anniversary of the last of the boomers. It seemed like a great moment, and everyone is still pretty vibrant. Everyone is still active and doing cool things, and that was a big part of the motivation.

D: How did you select the particular group of people who appear in the film?

TGS: It was like working on a Rubik's Cube in the dark. It was very difficult to figure out who belonged in it, and I had restrictions that I placed on myself. I wanted to balance it with men and women. I wanted to have diversity and try to limit the categories so if there was a musician picked—let's say Billy Joel—I didn't get to pick two or three other ones. I would have liked to have picked Reverend Run for 1964 but I had Billy Joel, so I ended up with John Leguizamo.

John Leguizamo, from Timothy Greenfield-Sanders' The Boomer List. Courtesy of (c) Timothy Greenfield-Sanders.

I'm very proud of the film. It shows the real range of the generation. I wanted to show Erin Brockovich. I wanted to show Steve Wozniak. I wanted to show all of these tremendous changes that happened and the people who helped make those changes.

D:How much time did you take with each subject?

TGS: At least an hour and a half to two hours. It's Timothy Greenfield-Sanders portraiture comes to life! Also, I photograph everyone, so they came for the interview and they'd sit for a large-format portrait on my 8X10 camera as well. Those portraits are opening on September 26 at the Newseum in Washington, DC.

D:The thing that I find most fascinating is that even though these are essentially talking heads, they're dynamic. What kind of magic are you working there?

TGS:I always believed that, when you looked at my portraits that were hanging in galleries or museums, people could look at them for a while and get something out of them. Then I always thought, If they could talk to you it would be even more interesting. I wanted to light everyone the same way as that. Over the years I think I've developed a very personal, distinctive style of portraiture. It's a single light source. It's a very clean background. It's never about the setup or my fancy lighting. It's always about the subject. That's what works.

Direct-to-camera talking is so powerful. When we started The Black List, Errol Morris was doing it and that was about it. If you look today, every commercial, Academy promos, Gap commercials—everybody does direct to camera. The over-the-shoulder look is gone. The reason it works is that it's much more intimate. It feels like the person is talking to you.

D: But then there are some people who do it better than others.

TGS: (Laughing) Am I allowed to call myself a renowned portrait photographer? I know how to light people. There are ways to do it with a certain elegance that really heightens the effect, and I hope that comes through.

D: What were you shooting with?

TGS: We're now using the Red. It's all technology at this point, and resolution. We used to use the Panasonic HVX200. When we shot with that system we used two cameras, one on top of the other- one close-up and one medium. Now we use one camera with much higher resolution.

D: When you were editing, how did you break down the interviews to achieve the film's narrative effect?

TGS: There's an arc to each of these little stories. You look at the hour interview and you throw out the obvious stuff that didn't go anywhere, and in some cases you have so much good material that it's very difficult. In other cases it's pretty clear where the storyline is. I think the other thing that comes into play is what other people have said in the film. You don't want everyone talking about the Kennedy assassination, even though it's such a seminal moment.

Take Sam Jackson, for example. I think it's a wonderful piece because he talks about segregation and growing up and education, and I don't think you ever hear that from him. We tried to find things that people hadn't said before, or said them better this time.

D: You started out at AFI. Was your intention to become a filmmaker and you became a photographer, or vice versa?

TGS: As a teenager I was influenced by Warhol and underground film, and I came to New York and went to Columbia and got an art history degree. I became friendly with some of the Warhol people and that was my direction. Then I went to AFI to learn film. At AFI you would see every film by Bergman, and then Bergman would come to campus and the 25 of us students would sit and have a seminar with him.

They needed someone to photograph the seminar guests for the school's archive, and no one else would do it. So I said I would. They paid $25! I would photograph all the visiting dignitaries, but I had no idea what I was doing. One day I was leaning down and shooting Bette Davis' portrait and she said, "What the fuck are you doing? You're shooting from below. You never shoot from below." I said, "I really don't know what to do." So she said, "If you can drive a car, I can teach you about photography." So I drove her around and she talked to me about [George] Hurrell and all the great photographers who had shot her.

I photographed Hitchcock and he said, "Your lights are in the wrong place. They should be over here. Come over to the studio and I'll introduce you to the lighting people." I fell in love with portraiture, and it was really through these legendary Hollywood stars that I learned it. By the time I finished AFI I had a very interesting portfolio of very famous people. Long story short, I bought a large-format camera and became a portrait photographer.

Environmental activist Erin Brockovich, from Timothy Greenfield-Sanders' The Boomer List. Courtesy of (c) Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

D: Do you have any more Lists planned for the future?

TGS: I have been working on The Women's List for a while. It's nearly done. We're just trying to figure out where it's going to end up. It has a few more spots available in it and we've done a number of amazing people.

Elisabeth Greenbaum Kasson is a Los Angeles-based writer and editor whose work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Documentary, Los Angeles magazine, Movie City News, Dice.com, Health Callings and more. Her stories have covered the gamut from movies, music and culture to IT and healthcare.

20,000 Days, 57 Years and 90 Minutes with Nick Cave

Some documentaries instill rage and inspire action. Some reveal and take you behind the scenes. Some speak to you directly and chase an explicitly political agenda to their finish. Some polemicize and educate. Some cut a path through an formerly erased history. And others, like 20 000 Days on Earth, draw you in emotionally and challenge the parameters of documentary-making.

Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard's film does not reside comfortably within any of the genres you might expect from a Nick Cave music film covering the 20,000th day of the legend's life: rock 'n' roll doc, biopic, indie character study, MTV-style promo video. Rather, the filmmakers, by necessity, approached the film as they would a narrative feature, capturing Cave's songwriting sessions; road trips in a black BMW with famous friends; pasta and anecdotes about Nina Simone and Jerry Lee Lewis, with bandmate Warren Ellis; a therapy session with psychoanalyst Darian Leader; and a rummage through Cave's personal photographic archives. Cave himself provides the narration, ruminating about time and memory, the creative process, living in a story and telling it, and "the space where imagination and reality intersect."

Nick Cave (left) and pop artist Kylie Minogue. Courtesy of Drafthouse Films

"We were very aware that we were telling a story rather than writing a biography," says Forsyth. "We saw the film as a portrait of Nick, in the same way that you paint a portrait or you photograph a portrait. There are different ways of doing that that aren't strictly journalistic, that can be more impressionistic, more like storytelling. Pretty simply, we set scenes up in a way that you'd set up a dramatic feature. There was a lot of art direction and there was a shooting script, for that reason. Once those things were in place and we were shooting the scenes, we shot it like you'd shoot a documentary—the cameras would take a step back out of the sightline and we'd be in a much more observational role."

Nick Cave's self-made status as a man of myth in popular culture also cemented the need for a fluid approach of scripted, structured, emotionally driven documentary that could evoke the images and words and sounds of the musician's inner world, which his outer world has collapsed into over the decades. Says Forsyth, "We felt very strongly—with the mythology that surrounds Nick in particular, and characters like Nick who have been, for 35 years, creating that mythology and building that mask-that there comes a point where they become the thing they've created. There's been a real tendency, particularly in music films, that somehow we can get behind the mask and reveal something more authentic, revealing the normality of these peoples' lives: a rock star cooking his own dinner, or driving the kids to school, or washing his car-an ordinariness that we can identify with."

Nick Cave with his kids. Courtesy of Drafthouse Films

Though Cave comments at one point that his ex-Birthday Party bandmates, like the deceased Roland S Howard, seemed to have arrived in the world fully formed, the film gives the same impression about Cave himself. "We wanted to give that really calcified sense of character that Nick has," says Pollard. "There isn't a normal bloke in there. He's gone. He's become the thing he's created, and he is that thing all the time. It's not a bad thing; it's an amazing, impressive thing. But it does mean that it's hard to feel a normal human connection to him."

And yet, Pollard maintains that "two different Nicks" still co-exist. "When you talk about the Nick and the mythology that he chooses to promote, what we're more accurately talking about is what the media chooses to promote. He chooses to hang onto some of those very powerful tropes like the black crow king, and we want him to be this dark, Gothic source, and he is, as a performer, tremendously imposing. But as a person, and even in interviews, he's remarkably open; he's funny as hell. And we just set about documenting, capturing, portraying the Nick we know—and the Nick we know laughs a lot."

Nick Cave with bandmate Warren Ellis. Courtesy of Drafthouse Films

"Honestly," Pollard continues, "a lot of the articulation you hear from Nick came about in the edit. That was very much a crafted thing—to take it back into the world of cinema fiction, so it assumed this tightness and consideration. The original discussions we recorded were a lot more sprawling. In his conversation with [the psychoanalyst] Darian Leader, they end on that hanging question of his dad's death. That didn't happen at all in reality; that was totally constructed in the edit. Nick talked for about an hour about his dad and finding out about his death—and it didn't have that power. It wasn't working on those two levels that Ian and I are often looking for: It's not just what we're telling you; it's what we're making you feel and showing you. That's what paints the whole picture. By positioning the talk of his dad's death at the end of the interview as this pregnant, unanswered question, we were able to also make you feel the emotional truth: that the death of Nick's father has had an enormous influence over everything else he's ever done, and is still unresolved. His father's death at that age [Cave was 19] is an open, hanging thing. We knew that we could craft that and make you feel it. So some of the truths are also our truths; they're the decisions we made as filmmakers."

"We recognized that every type of documentary-making is a manipulation of its subject," says Forsythe. "There's been so much change through reality television and all these things that have made audiences be aware of sophisticated ideas to do with mediatization and the presentation of an image. If we'd made a film, maybe five or ten years ago, and shot it TV-style, with grainy, handheld cameras, I think everyone would've come to the assumption that it was very 'real,' very authentic, that we were merely following Nick around. Because these days, this new visual imagery is part of our culture; shows like Homeland and American Idol and all of these devices are very familiar to an audience now. They know they're being manipulated. "

That knowledge of manipulation makes it an exciting time for Forsyth and Pollard to venture into documentary territory. In the last decade or so, we've moved from director-dominant, polemical films like Michael Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11 and Davis Guggenheim's An Inconvenient Truth that have impacted the international conversation, to hybrids like Joshua Oppenheimer's The Act of Killing and Sarah Polley's Stories We Tell that have tested, the possibilities of the documentary form, for both filmmakers and audiences

But in the end, it was the unavoidable commercial process of distributing the film that nudged the filmmakers toward a tangibly circumscribed cinematic area. "When we first started," says Pollard, "we didn't really think about what sort of a film we were making. There was no need to classify it. We didn't even think of it in terms of documentary or not. We just set about making a really good film. It was only when our sales agent was submitting to Sundance, we went, 'OK, we've made a documentary!'"

Forsyth continues, "It's something we're very used to, having worked together as artists for 20 years. There always comes a point to define. People need to be able to label things to make them simple, either for administration or for understanding. 'You're a video artist...You're a documentary-maker... You're a singer/songwriter...' It's inevitable, but weird when it comes, because during the process of making, they're not things that are at the forefront of my mind."

More forefront was the driving idea of Cave's fear of being forgotten. "You want your days on earth to have meant something," says Pollard. "You want to leave however small a mark in the world, and I think that is what we all want to do. To be a spectacle but not to be remembered? That's a tough dichotomy. [Cave's] reason for existence is to be remarkable, to be the center of something, to be spectacular and to entertain."

Lauren Carroll Harris is a Sydney-based writer and the author of Not at a Cinema Near You: Australia's Film Distribution Problem, published through Currency House.