Our Nixon takes audiences on an intimate journey inside the White House during the presidency of Richard Milhous Nixon. The 84-minute documentary begins in 1969 with the inauguration of Nixon as the 37th President of the United States, and concludes with him resigning in 1974 in the wake of the Watergate scandal and the threat of impeachment by Congress.

The independent film was co-produced by director Penny Lane and Brian Frye under the label Dipper Films. Primary content is seen through the eyes of Nixon Administration Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman, Domestic Affairs Advisor John Ehrlichman and Special Assistant Dwight Chapin, who documented their experiences with home movies recorded on Super 8 film.

The documentary provides unique insights into the character of Nixon and his staff as well as the issues of the times. A short list of the home movies includes Nixon watching television images of lunar landing of the Apollo 11 astronauts; anti-Vietnam War protests outside of the White House; the 1969 inauguration ceremony; Nixon and his wife, Pat, announcing that their daughter Tricia is engaged to be married; and film of him dancing at her wedding.

There are images of Nixon meeting with Premier Chou Enlai and attending a ballet with Chairman Mao Tse-Tung, head of the communist party, during a visit to China. There is also Super 8 film of Nixon meeting with the Pope in Rome. The Super 8 film was archived at the Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California and at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

There is also content edited from archived television news film and almost 4,000 hours of White House conversations recorded on audio tape. One example: Chapin talking about Nixon wiping tears from his eyes as he wrote notes to the parents of soldiers killed in Vietnam.

There is news film of former US military analyst-turned-whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg at a rally calling for Nixon to stop the bombing in Vietnam. There are news film images of Vietnam War veteran—and current Secretary of State—John Kerry making an anti-war speech. Other archived news film includes journalists Dan Rather, Walter Cronkite, Barbara Walters and Mike Wallace talking about Nixon and his administration.

The documentary aired on CNN network earlier this month, and makes its theatrical debut August 30 through Cinedigm.

Our Nixon is the first feature-length documentary credit for both Lane and Frye. Lane has been producing and directing nonfiction and essay films since 2002. Frye is a law professor who has produced a few experimental films.

"I met Penny about 10 years ago," Frye recalls. "I had heard about the home movies taken in the White House. We agreed to explore the possibilities of producing a documentary looking back on the former president based on the home movie footage."

"Too much history is shaped by people writing or speaking about it," Lane observes. "Brian and I agreed that going back to the primary source is the best way to experience history as it was lived. We watched the home movies, TV interviews and news clips and listened to oral histories recorded on the White House audio tapes.

"Our Nixon is not an attempt to write a tied-up history with only one ultimate meaning," Lane maintains. "Nor is it an attempt to convince you of my point-of-view. Rather, the film asks audiences to sift through the fragments of history in order to reach their own conclusions." Some 26 hours of Super 8 film was found in Ehrlichman's office after he resigned. It was converted to 16 mm color internegative stock at 18 frames per second at NARA.

Lane and Frye contacted NARA in 2010 and arranged to make a telecine copy at standard definition. In 2011, they heard that the Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California, had another set of the collection. They met with Ryan Pettigrew, the archivist at the library, and discovered these were the original films, obtained from the Haldeman estate.

"We offered to pay for an archival-quality scan at 4K resolution," Lane says. "We hired Jeff Kreines, who invented the Kinetta film scanner, to travel to the Nixon Library. He scanned every frame at four times the resolution of HD video and delivered the content to us as digital Cineform files at the native 18 frames per second."

"Our collection consists of 55 original, 400-foot-long reversal film reels, each of which consists of shorter reels edited together during the Nixon administration," Pettigrew says "They were donated by Haldeman's wife. There is another collection of Super 8 reels that is referred to as the 'White House Staff Super 8 Collection.' These films were found in John Ehrlichman's office during the Watergate investigation.

"The second collection consists of 55-second generation prints on seven-inch reels," Pettigrew continues. "For the most part, they mirror the Haldeman collection. It is evident that Haldeman made some edits in the years following the Nixon Administration. There are 94 reels in the Ehrlichman duplicate set that were not compiled. There are separate 50-foot reels on three-inch hubs. Most of them appear to be second-generation contact prints. The location of the original reels isn't known."

The documentary was edited by Francisco Bello, who earned Oscar and Emmy nominations for Salim Baba in 2007 and an Emmy nomination for War Don Don in 2010.

"The reactions have been really positive," Frye says. "My impression is that a lot of people weren't sure what to expect. When they see the film, they are pleasantly surprised by how interesting, intimate and personal the movie is. Nixon and his staff members were almost comically square in a way—sometimes a little silly in a creepy way, but still funny.

"I think the film gives audiences insights into the Nixon presidency," Frye continues. "We tried our best to represent that as accurately as we could. You have to remember that Nixon was elected by a significant majority of votes; that paints a picture of what America was like and what people cared and were concerned about. It's important for people in my generation to fully wrap their heads around that part of history. This film is kind of tactile, first-hand way of experiencing it.

"Obviously, archived images are a great resource," Frye asserts. "We need more people to appreciate how to use archive material in thoughtful ways to educate future generations about the past. Unfortunately, I don't think we will ever see this happen again. No president after Nixon allowed the documentation that took place during his regime. The level of documentation that the Nixon Administration encouraged and facilitated won't happen again. They are going to want control over what's recorded and how the administration is represented.

"Ryan Pettigrew was hugely helpful," says Frye. "He is really a hero in the making of this movie. He told us that the Nixon Foundation had just given the Nixon Library the original Super 8 film that they received from Mrs. Haldeman. The difference is stunning. The sharpness is incredible."

Preservationist Milt Shefter observes, "It is important for documentarians to be able to tell history-based stories using visual and aural records of the past. We should all be concerned that the transition from film to electronic news reporting will limit that capability in the future."

Shefter and Andy Maltz collaborated on researching and writing the The Digital Dilemma Two archiving report sponsored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences that was published in 2012. The report focuses on the archival status of independent American narrative films and documentaries. It is available on the Academy website. For an article about The Digital Dilemma 2, click here.

Bob Fisher has written more than 2,500 articles about narrative and documentary filmmakers over the past 50 years. He has also written extensively about the importance of archiving yesterday and today's films for future generations.

A Conversation with CNN's Vinnie Malhotra

Vinnie Malhotra is senior vice president of development and acquisitions for CNN. Documentary spoke with Malhotra about how CNN chose Our Nixon and other independently produced documentaries to air.

Documentary: Is CNN showing more documentaries than it has in the past?

Vinnie Malhotra: CNN and a few other networks are showing more documentaries. The marketplace for high-quality documentaries has become incredibly competitive.

D: How do you decide what documentaries to air?

VM: We consider airing documentaries for various reasons. We look for documentaries that take us beyond what we know about important issues. Questions that we ask ourselves include whether the film tells a deep story about an important subject, and is it high quality. In the case of Our Nixon, what was so compelling was that it wasn't just another film about Watergate or the Nixon administration. It is one of the most creative approaches to telling the story of the Nixon Administration and politics, in general, that any of us had ever seen. The fact that Penny Lane didn't shoot a frame of film, but managed to piece together such an incredible story from archives was wildly eye opening for us.

D: Can you give us another example?

VM: Steve James is working on Life Itself, a documentary about Roger Ebert. The executive producers are Martin Scorsese and Steve Zallian. We got in very early with that project. Roger Ebert and his colleague Gene Siskel are populist film critics who changed how we speak and feel about movies. They found a rightful place in American pop culture.

D: How do filmmakers get CNN interested in their documentaries?

VM: Anyone can propose projects at any stage of development. Courtney Sexton plays an important role. She recently joined CNN as a senior director. Courtney has been working with Diane Weyermann at Participant Media for the past six years.

—Bob Fisher

Takeaways from the Sundance Creative Producing Lab: Prepping Your Doc for the Marketplace

"This is a place where you can breathe deeply," advised Cara Mertes, director of the Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program and Fund, during the opening dinner of her final turn overseeing a Sundance Institute Creative Documentary Lab, after seven years at the helm. The Creative Producing Lab, held in late July, brought together seven documentary producers (referred to as fellows) with four expert advisors for an exceptionally intensive week of give-and-take. The producers' respective projects were discussed at length and rough cuts were screened, with the intent of clarifying any story and structure glitches. The advisors and fellows analyzed funding issues as well, within the context of completing the projects and getting them out to the marketplace.

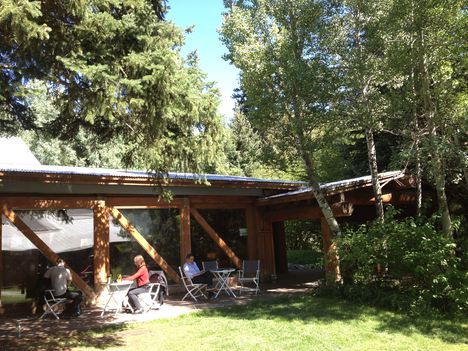

The lab, which was followed by a weekend-long Creative Producing Summit, took place at the busy Sundance Resort, set among pines and aspens in Utah's Wasatch Mountain Range. Originally a small family-owned ski area when purchased by Robert Redford in 1969, now a chic, eco-minded resort, the property is the birthplace of all things Sundance: the institute, the festival, the catalog and the invitation-only filmmaker labs.

The buildings are low-slung and purposefully rustic, many constructed with reclaimed wood; an alpine stream runs between them, set against the rugged butte peaks of Mount Timpanogos, often ringed in stunning cloud formations. The altitude plays a part in the feeling of possibility, while the mountains enhance the sense of openness that participants are quick to remark upon. The inspirational physical setting defines the labs and influences the tenor, tempo and depth with which participants can delve into their work. The other Creative Documentary Labs include the Documentary Edit and Story Lab, the Composers + Documentary Lab and the New Frontiers Lab. The latter takes place in October, while the former two happened earlier in the summer. "People are different in this space," Mertes asserts. Practicalities are provided for the filmmakers, from meals to ultra-comfortable digs in the quiet canyon.

"Being taken care of is so powerful for people—especially in the resource-constrained documentary community, where you're taking care of the story, your subjects, your family, your film," Mertes explains. The labs go beyond logistical work, sometimes even tackling the stymied dynamics of a filmmaking team. "In the independent community, the work stems from passion and commitment," Mertes says. "If you're not OK, your film is not going to be OK, because the two are completely inter-related. We don't ignore the heart or the head: it's both."

During the labs, Mertes stays in the background, guiding conversations and sessions rather than directly leading them, interjecting when she thinks there’s something important to add. Her firm and sure point of view is there for the asking, and her deep knowledge of all available avenues to filmmakers comes from her more than 20 years devoted to the genre.

Founder Robert Redford and the Sundance Institute's remarkable legacy and past lab fellows' accomplishments are ever-present through the resort's many photos from past workshops (many participants are Academy Award-winners, including Redford himself). Posters from festival- and lab-supported films line the lobby of the screening room. In this rarefied setting, fellows, who are chosen from the wide-ranging field of Sundance Documentary Fund grant recipients (45-55 projects are awarded annually), are given the freedom and artistic support to tackle the problems and challenges of their respective projects.

Everyone who participated in the lab was awed by the setting, the remarkable opportunity and the engaged community. Creative insight, real-world experiences and practical information were shared freely, but with a major caveat: participants (including this writer) had to sign a non-disclosure agreement. In exchange, the filmmakers received an honest assessment of today's marketplace and detailed, thoughtful advice from the experienced advisors on hand.

Many of the most tantalizing anecdotes about buyers were deemed confidential, as was the private screening of an upcoming Toronto premiere, reactions to rough cuts, cautionary tales about equity investors, and specific project budgets. However, the advisors and fellows' willingness to speak candidly off-the-record about financial details and past conflicts enriched the experience. Fellows were able to detach from their filmmaking process somewhat; the lab is designed to give the selected projects a mighty push to the next level in the creative process: completion and eventual distribution to a global audience.

Each film was considered as an individual case study, with emphasis on both subject matter and festival strategy. Although most filmmakers may dream of theatrical distribution, those aspirations need to be realized in today's distribution landscape, where release strategies are ever-evolving.

This year's lab participants were Elizabeth "Chai" Vasarhelyi, director/producer of An African Spring, about political upheaval in Senegal; Rachel Lears and Robin Blotnick, co-directors/producers of The Hand that Feeds, which chronicles the efforts of fast-food workers to organize in Manhattan; Carola Fuentes, director/producer Chicago Boys, a look into Chile's economic and political past; Hillevi Loven, director/producer, and Chris Talbott, producer, of Radical Love, about cultural change through the lens of one relationship; and producer Sarah Archambault of Street Fighting Man, which follows three Detroit residents as they grapple with the city's demise.

In addition to Mertes, creative advisors were Submarine Entertainment's co-president Josh Braun; David Magdael, president and founder of the LA-based publicity firm David Magdael & Associates; producer Bonni Cohen, who runs San Francisco-based Actual Films, the company behind The Island President; and Motto Pictures' Julie Goldman, producer/executive producer on such documentary features as God Loves Uganda and Gideon's Army.

Not surprisingly, the need for additional fundraising and finishing funds was a challenge shared by all the participants. What follows is a recap of some of issues discussed.

Equity Financing

"A lot of people want to date us but no one wants to marry us," quipped Cohen about the documentary producer's quandary. Producers need to ask and determine where to take risks financially outside of foundation funding, and should consider carefully when bringing in equity financiers. With funding comes expectations about credit and creative control. And although crowdfunding campaigns can raise an amount equal to or more than a grant, advisors recommended caution regarding incentives promised via the campaigns, due to the manpower and expense involved. Do the math on the costs, and study what has worked previously.

Safeguard the Subject

Subjects of documentaries can be exposed in a very invasive way and vulnerable subjects need to be prepped in advance of screenings and Q&As—and ascertained if it's even appropriate that they're included, advised Magdael. Although a subject might consider the film their possible economic lifeline, it is most likely an unrealistic expectation, and should be addressed in advance.

If there are controversial elements in the film, keep close control of social media and be strategic and cautious before the film's premiere. Even when a film premieres at a major festival, consider scheduling key constituency screenings and a homecoming premiere for those who are natural advocates for the film.

Realities of the Sales Process

In the end, the business is all about relationships, and filmmakers should be working with their sales agent, publicist and distribution partners as a team. "It's not a science," explained Braun about the sales agent's role. "You have to dream and think big and understand limitations at the same time." Sales agents need to counter a producer's expectations with their financial obligations. Deal structures are different from film to film, but sales deals that split the rights can often net more in total sales.

On the upside, documentaries are more embraced in the marketplace. "It's incumbent upon filmmakers to talk with other filmmakers about broadcasters and sales agents and to confirm why or if it worked for them," recommended Braun.

The Importance of a Festival Run

In today's competitive marketplace, a festival run indicates a stamp of approval that is used as shorthand by buyers. Each major tier festival has some meaning to buyers, and although most films will not be accepted into Sundance, other festivals and screening series (and their attendant publicity and audience) can be just as important to a film's distribution.

Authenticity

"Be authentic: That's the bottom line and that's why audiences are responding," Mertes asserted to the fellows. She noted that the power of chronicling real emotions, conversations and relationships has a real effect. Keep the work grounded and true.

Kathy A. McDonald is a Los Angeles-based writer.

The Mertes Era: Outgoing Sundance Doc Program Head Reflects on Her Tenure, Looks Ahead to Ford Foundation

As director of the Sundance Institute's Documentary Film Program and Fund (DFP), Cara Mertes oversaw the organization's largest initiative, and worked tirelessly to expand its funding sources and reach. In September, she joins the Ford Foundation as director of its JustFilms program.

During her seven-year tenure at Sundance, she expanded and strengthened the DFP's partnerships, linking up with the Skoll Foundation, Good Pitch/Channel Four/BRITDOC Foundation, TED, the Hilton Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, among others. Additionally, she focused on international initiatives, such as the Skoll Foundation-backed Stories of Change.

Documentary spoke with Mertes in Utah, between sessions at her final lab at Sundance. (For an article about the 2013 Creative Producing Lab: Documentary, click here.)

Documentary: What's changed during your tenure?

Cara Mertes: When I came here, there were two labs that dealt with four films each, and maybe 10 to 12 artists. Seven years later, there are six labs and fellows opportunities that work with 100-plus artists over the course of any given year. Fund granting is now about $1.5 million per year, plus funding for special opportunities that develops every year.

We've grown the fund program and labs and we now have about 50 films that we fund every year; since production goes over several years, we might have 60 to 70 in some of production or distribution.

D: There are now grants to continue work initiated at the labs. How did that evolve?

CM: At the labs, we realized we were doing such a great job of retooling and redirecting that [filmmakers] needed a little help to get on that path. There's a 100 percent completion rate coming out of the labs, and they generally have a good festival premiere, whether it's Sundance, Berlin, Tribeca, True/False...These films really find homes.

D: What are your hopes for your successor?

CM: My goal in talking with Keri [Putnam, Sundance Institute's executive director] is, we would keep everything on the table. I've developed a whole wing of creative partnerships that didn't exist before. The program is now a fund, extended artist support and labs, and a whole suite of extended creative partnerships that are generally international in scope. All of those are very much defined by opportunity, my commitment to increasing resources to the field, and natural allies.

A lot of those components have been developed because I want to see documentary grow in a certain way around the world. Some [documentaries] have been brought to us, and increasingly foundations are coming in and want to have a special fund; they are all interested in nonfiction and so we kind of house them. If they're tending to be more cross-Institute, we'll pull from New Frontier and from the feature film program, but because the program is doc-heavy, they'll live in the DFP. Those approaches will continue to come in and it will be up to the new person to either continue to evolve those partnerships, and those international labs-or he or she might say, "We really want to grow the fund right now; we want to focus on the labs right now." It really depends on their vision of the documentary world and what it needs, and what Sundance is most appropriate for launching.

Sundance is really good for certain things but not really built to be other things. For instance, I became much more of a producer/executive producer here than I intended to, but that's my background. But Sundance is not built to be a producing entity at all. I've been holding that at bay because there have been constant requests to have us get involved at the level.

D: What will you be doing at the Ford Foundation?

CM: I'm going to be a funder for the first time; I have a $10 million portfolio. So I'll be giving away $10 million a year. I have to give it away. And I've been told in no uncertain terms that it's harder than I might think.

D: How does one apply?

CM: There's a whole Ford Foundation application process I'll be looking at. It's a really great initiative that's only three years old. So it's a perfect time to take a look at it and work with the foundation and field stakeholders, many of whom I work with now, and say, "Now what?"

D: So the funds are distributed to institutions and filmmakers?

CM: Yes, both. That's how they came to know me, as there are three organizations that receive $1 million a year: ITVS, Tribeca and Sundance. And they launched a $50 million commitment at Sundance three years ago. Those commitments will stay intact, and the rest of the $7 million goes to a combination of institutions and films. I'll start granting in 2014.

D: After working in New York for 20 years, and LA for the last seven, what are your thoughts on the East and West Coast documentary communities?

CM: When I came out seven years ago, there was a strong and growing community in LA, and seven years later it has grown a tremendous amount. I think the Academy (of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences], of which I'm now a member, has made documentary a priority and it's a very active branch. It's galvanized a lot of documentary filmmakers who live in the LA area. San Francisco and LA combined is a really big community; New York/Boston is where most documentary is done, second is San Francisco, third is Chicago. [Documentary is] finding a lot of practitioners: editors, distributors, people attached to the independent community. It's becoming a very vibrant space to be. We have corporate sponsors interested in nonfiction and its power. There's a lot of activity and interest now.

Kathy A. McDonald is a Los Angeles-based writer.

For an interview with Mertes when she first started at Sundance in 2006, click here.

Just before the sharp curve in the road where Sunset Boulevard officially becomes the bustling Sunset Strip sits the unassuming Directors Guild of America building, home to a year-round selection of public events and private industry screenings—and this year, the destination for the 31st installment of Outfest Los Angeles. One of the first and only film festivals in the world to focus exclusively on stories made for, by and about gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender persons, Outfest is this community’s primary cinematic source for stories otherwise marginalized or flat out ignored by mainstream media.

For 10 days in July, the DGA was transformed into a constant flow of moviegoers buzzing with excitement over the wealth of LGBT programming options. Highlights of the festival were strongly tied to a sense of place and history, with stories straight from the heart of America's Deep South and Central Africa sharing the screen with beautiful and entertaining portraits of famous LGBT figures from recent history and current popular culture. With so many important and contemporary stories mixed into the jam-packed Outfest schedule, having to choose from the 19 documentary features was no easy task. Of the ten nonfiction offerings that I saw, the clear standouts—outside of the three main award winners—were the moving, daring and sometimes shocking profiles of three famous American figures.

If you were tuned in to current events in the summer of 2011, you were probably following the story of long-distance swimmer Diana Nyad's attempt to complete the 103-mile open water swim from Cuba to Florida. While news cameras were primarily covering the aftermath of her three failed attempts, Nyad's nephew Timothy Wheeler was there with his camera for every part of her journey for the making of his debut feature, The Other Shore. Nyad is the narrator throughout the journey, with candid interviews reflecting on her accomplishments and failures intercut with the often excruciating footage of the athlete pushing through each of her three attempts to complete this swim. Tense moments spent struggling with box jellyfish stings and asthma attacks are captured with the little light available to the camera crew out on the open water, but the vérité footage never feels too dark or grainy. Nyad's unflagging tenacity is consistent through even these failures—failures that to a weaker soul might seem dream-crushing. Her incredible strength of character makes The Other Shore one of the most inspirational stories to come out of this year's festival.

For one of the festival's special gala screenings, a packed theater sat engrossed in the life of one of America's most famous and controversial Pulitzer Prize-winning authors during Pratibha Parmar's Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth. Perhaps best known for her 1982 novel The Color Purple, Walker has also written dozens of novels, poetry collections and works of nonfiction, many of which are highlighted by scores of her contemporaries, fans and friends who are interviewed throughout the film. Each time the likes of Howard Zinn, Gloria Steinem, Sapphire or Danny Glover appeared onscreen, little stirs and grins of excitement spread through the packed house and added another layer of joy to the viewing experience. Walker herself is a strong presence throughout the film, making the viewer grateful to Parmar for having the ingenuity to make this film while this famous writer is still alive. Somewhat of a living tribute to a woman whose views on love and the world around her are as beautiful as the images Parmar chose to accompany this writer's story, Beauty in Truth stands strong as a worthy portrait of an American literary icon.

A depiction of a famous figure that could not have stood in more direct contrast to the poetic sincerity of Beauty in Truth is Jeffrey Schwartz's I Am Divine, a full-frontal confrontation of John Waters' most glamorous and flamboyant muse. Fans of the self-proclaimed "Queen of Filth" are invited to look deeper into the life of Harris Glenn Milstead, the chubby, queer friend of Waters from their hometown of Baltimore who went on to become one of most iconic and legendary cult figures of the last century. Complete with clips from rare home movies and outrageous live performances, Schwartz's film about this larger-than-life outsider maintains an air of respect and reverence for a figure who stood up for millions in the queer community throughout his short life and career. Schwartz's film emphasizes that this performer was more than a postmodern amalgam of '50s glamor, '70s disco and '80s excess, and the interviews with Divine's late mother reveal this performer's underlying humanity.

Through the stories of four people each affected by the AIDS virus, Special Programming Award for Freedom winner deepsouth (Dir.: Lisa Biagiotti) puts a face on the problem of HIV/AIDS funding in the American South. The narrative floats between the lives of an HIV-positive black gay man, the director of AIDS Alabama, and two women who run a severely underfunded AIDS retreat in Louisiana. With beautiful, impressionistic camerawork and a refreshing lack of first-person in-studio interviews, deepsouth unfolds lyrically to underscore the importance of AIDS policy and awareness. This snapshot of the four figures and those around them whose lives are impacted by HIV/AIDS maintains a neutral tone, allowing the viewer time to develop genuine empathy and compassion for the folks who struggle mostly out of sight from the rest of the country. deepsouth allows those voices to be heard, and allows their plight to not go forgotten.

A similarly impressionistic style of filmmaking is found within Shaun Kadlec and Deb Tullmann's Born This Way, this year's winner of the Grand Jury Award for Outstanding Documentary Feature. The film takes us to Cameroon, where individuals can be sentenced to anywhere from three to five years in jail if they are caught engaging in homosexual activity. We take a look inside Alternative Cameroon, a center for homosexual rights that receives most of its funding for HIV care and treatment, but cameras also spend time in bars, nightclubs and bedrooms documenting the normal routines of gay and lesbian men and women in this Central African nation. Kadlec and Tullmann shot in darkness and through candlelight at times for tone, at times for necessity; keeping the identities of interviewees protected was of the utmost importance. While most of these individuals are not out to their families, they are comfortable enough to live their lives fully around their peers and fellow LGBT activists. Much like deepsouth, Born This Way is far from a cry for help; more so, both films serve to highlight those working on the ground in the constant struggle for hometown representation and appreciation, and global equality.

Katharine Relth is the IDA's Web and Social Media Producer.

The central idea of Good Pitch—building support and connections for documentary film that can make a significant impact on social issues—is hardly new for Latin American film. As far back as the late 1950s, Fernando Birri's work with film students in the shantytowns of Rosario, Argentina, put a focus on social issues that were completely ignored by the media at the time. And Patricio Guzman's landmark trilogy, The Battle of Chile (La batalla de Chile, 1975-79), about the military coup that violently put an end to the democratically elected social government of Salvador Allende, became an important tool among international human rights movements. More recently, Enrique Piñeyro has been exemplary with films that have had a direct impact on Argentine aviation safety legislation (Fuerza aérea sociedad anónima, 2006) and, in 2010, a film that focuses on arrests of innocent people by corrupt police (El Rati Horror Show) that has become central evidence in a criminal case.

However, as film production has increased in the region over the past decade, while traditional distribution channels have become more limited, it has become even more difficult for documentary films to reach their target audiences and create social impact. With this reality in mind, Good Pitch organized its first Latin American edition on Saturday, August 10, in Buenos Aires, within the framework of Argentina's international human rights film festival, DerHumALC XV.

The program presented four films covering a broad range of subjects: territorial conflicts in the north of Argentina (Territorios, by Julian Perini Pazos); the negative impact of US free trade agreements on small farmers in Colombia (Victoria Solano's 9.70); the struggles of a girls soccer team in one of Buenos Aires's poorest shantytowns (Mujeres con pelotas by Gabriel Balanovsky and Ginger Gentile); and the story of generations coming together as part of the free public education movement in Chile (Edison Cajas' El vals de los inútiles).

Headed by Bruni Burres of Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program and Patricia Finneran of BRITDOC, and with strong support from festival director Florencia Santucho and the DerHumALC XV staff, the Good Pitch team convoked an important representation from NGOs, academia, government and the film world to the table to discuss and pledge support for these films. In the case of El vals de los inútiles, for example, support was offered from Argentina's National Institute of Human Rights, the Argentine University Federation and Latin American School of Social Sciences (FLACSO).

The presentation for El vals de los inútiles (The Waltz of the Useless) was particularly powerful not only because of its aesthetic beauty and emotional material, but also because the film's theme was underscored by two factors—one, unlike in Chile, where education was heavily privatized under the military regime of Pinochet, Argentina has a strong tradition of public education that has attracted thousands of university students from all over Latin America including Chile, a fact that was very present with everyone in the Good Pitch audience, and at the table. Second, one of the two main characters of the film was tortured during the Pinochet dictatorship, and the pitches were held, not at all by coincidence, at the Memory and Human Rights Space (el Espacio Memoria y Derechos Humanos, ex-ESMA), housed in the former detention and torture center that was the Argentine Navy School of Mechanics.

Finally, it is important to note the presence of Good Pitch veterans Pamela Yates and Paco de Onis, who were on hand to share their experiences as part of the pitch training workshops that were organized for the participating producers and directors. Their film Granito: How to Nail a Dictator won the Grand Prize at the DerHumALC XV festival.

Richard Shpuntoff is a documentary filmmaker and translator who lives in Buenos Aires and New York City.

Filmmaker Zachary Heinzerling met multimedia artist Ushio Shinohara at an open studio in the Dumbo neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. Shinohara had gained some notoriety in the 1980s making sculptures from reclaimed cardboard and practicing a painting method with boxing gloves he called action painting, the roots of which could be traced back to the abstract expressionist movement. "I shot Ushio for three or four hours and he was immediately entertaining, a showman," Heinzerling says. "He did action painting for us and did a motorcycle sculpture in 15 minutes. He was referencing books he was [featured] in when he was in his 20s."

After some successful associations in his native Japan, Shinohara, now 81, moved to Soho in the early 1980s and there enjoyed the most press of his career. Despite a dearth of attention from the media since then, his creative energy has not waned.

Action painting begins like a gimmick. Shinohara's wife, Noriko, laces up his gloves and in regular intervals he dips his sponge-loaded gloves in buckets of paint. As Shinohara bangs out splattered squares of color on a giant canvas with his fists, you see this gimmick morph into a fight with the medium. The battle happens regularly and the winner is up for grabs. With Shinohara, much is laid bare in little time. After his first shoot with Shinohara, Heinzerling recalls, "We had this amazing insight into an artist we didn't know much about. And all this happened as Noriko chimed in from the wings."

Heinzerling realized that what he had was a relationship film. He considered making a film about their careers but, "I was more interested in how their personalities butted up against each other and blended together. It's about the way they love, rather than what love is to them." But both Noriko and Ushio are artists and the two have complex relationships with their work, which means when you watch Cutie and the Boxer, you're watching a film about more than one relationship. "From the git-go we knew that the more traditional style of investigating the history of their art wouldn't fit a treatment of these artists," Heinzerling explains.

Noriko manages Ushio but "isn't his assistant, but sometimes helps," as she explains in the film. The distinction is important because she has her own work and she assigns her husband some blame for her lack of prominence in the art field. She refuses the role of amanuensis as if it would be degrading. Before you begin to think there's a clear victim here, remember the action painting. Heinzerling's greatest accomplishment in Cutie and the Boxer is resisting our expectations of how love and relationships should look.

Precisely who is meant to win when these gloves are on?

Noriko and Ushio met when she was 19 and he was 40; he was getting press for making art out of found materials, and she was in art school. She got pregnant quickly, estranging her some from her work. He drank to forget his frustrations with success. Now in her 60s, she's begun a new series—a cathartic retelling of her love affair with Ushio. The protagonist of her illustrations is Cutie, and Cutie's lover/anchor is Bullie. For Cutie and the Boxer, love and resentment are chronic bedfellows.

"It's impossible to explain these relationships," Heinzerling confesses. "There's no real answer to the question 'Why are they still together?' It's a combination—them meeting, dependency, but also this spirit that's evoked when artistic personalities combine to create something new. They revel in the struggle. Their life is a struggle, and it's going to keep them going and keep them young. It's definitely a love-hate relationship."

Side by side, Ushio and Noriko didn't wait for Heinzerling to ask questions, which the director suggests took matters partly out of his hands. "They interviewed each other, which accomplished more than if each artist had his or her own questions." It also fills out the dynamic between the two, which is a system of levers and pulleys so involved it seems to be advancing as you watch. What isn't clear is how these two lovebirds avoided softening with age. "Beauty in its forms has an uglier side," Heinzerling notes. "The scars are as important to show as the love."

Ushio and Noriko are feisty and fierce and their love is often uncomfortable, but it's a driving force. "They live this very unique lifestyle where they expend a lot of effort and artistry in every aspect of life," Heinzerling says. "It's about the way they love, rather than what love is to them." And as Heinzerling describes, their actions can't match the clearly packaged expressions they produce for a living—the axiom "art imitates life" is only a half-truth here. Anyway, for Ushio, "Action is art," and action is a thing in perpetual motion.

The working paradigm looks like balance when Noriko is peacefully painting Cutie, and Ushio is violently bending found metals, but when they can't pay rent, Noriko henpecks, and Ushio responds, "She's average, I'm a genius." How anyone could create in such seemingly hostile conditions is a miracle, but this couple doesn't know when to concede. Heinzerling seemed to take strength from that. "I had ways of convincing myself to continue with the project even if, after years of work, it could turn out to be nothing," he admits. "I'm sure there are doc filmmakers who relate to that; you're following someone in the hopes this magic story will emerge." Cutie and the Boxer ends with a joint art show featuring work by both Ushio and Noriko. It's exposure they need, but it also feels like a trophy they earned for surviving the cage match at home.

"You come up with your own formula of how to keep going," Heinzerling says. "Ushio's convinced himself he's destined for this. Art is a devil, a demon that sucks you in and you have to give up worldly things to be a part of it." And just as you're thinking everyone in Cutie and the Boxer is in a prison cell too familiar to leave, you realize Heinzerling is finding the couple at a new phase: "Noriko just turned 60 and she's just decided to be confident in herself as an artist. Her art was always viewed in relation to her husband—and it is with Cutie—but it's a comment, a statement that comes from a grounded place."

Ultimately the key to their turmoil and affection is revealed in the film's climax: a wailing, drunken sob of exhaustion uttered decades ago. "There is something admirable about [Ushio's] pure connection between his beliefs and action," Heinzerling explains. "People can take that inspiration or question it, but for him it works and he is so energetic and dedicated, especially for an 81-year-old who hasn't had much in life. He has this appetite to create and show his work and teach and talk and entertain and he's nonstop, so this method works for him and keeps him going. There's something to say for that."

Ultimately the key to their turmoil and affection is revealed in the film's climax: a wailing, drunken sob of exhaustion uttered decades ago. "There is something admirable about [Ushio's] pure connection between his beliefs and action," Heinzerling explains. "People can take that inspiration or question it, but for him it works and he is so energetic and dedicated, especially for an 81-year-old who hasn't had much in life. He has this appetite to create and show his work and teach and talk and entertain and he's nonstop, so this method works for him and keeps him going. There's something to say for that."

Zachary Heinzerling. Photo: E. J. McLeavey-Fisher

Cutie and the Boxer opens in theaters August 16 through RADiUS-TWC.

Sara Vizcarrando is editrix of the release calendar at Rotten Tomatoes; a film studies instructor; and a blogger for http://movieswithbutter.

Taking 'Citizen Koch' to the Public: Filmmakers Deal and Lessin Reflect on a Post-PBS Year

The documentary Citizen Koch is finally in theaters, and has had a distribution journey as relevant as its central theme: the question of media integrity caught in the nexus between extreme wealth and political agenda. Directors Carl Deal and Tia Lessin take a hard look at the 2010 Citizens United v. the Federal Election Commission ruling from the US Supreme Court, which asserted that corporations had the same First Amendment rights as individuals, that spending money was a form of free speech, and that government could not restrict political campaign contributions. The film warns against the encroachment of media and democracy by big spenders, focusing among others, on conservative billionaires David and Charles Koch.

Up until April 2013, the Independent Television Service (ITVS), which provides significant funding for independent documentaries for public television and produces the acclaimed PBS series Independent Lens, had expressed support for Deal and Lessin's examination of deep-pocketed donors and their impact on the electoral process in the US. At the time, the film was titled Citizen Corp.

In November 2012, Alex Gibney's Park Avenue: Money, Power and the American Dream aired on Independent Lens. The film examines the issue on income inequality in America, and focuses on 740 Park Avenue, home for a large concentration of billionaires, including David Koch. Rumor spread that the film had raised hackles at WNET, the PBS affiliate in New York, where Koch was a benefactor and board member. According to a New Yorker article by Jane Mayer, WNET President Neal Shapiro threatened to stop airing ITVS programs, including Independent Lens, in the future. Koch himself withdrew a potential seven-figure gift, and resigned from the board in May 2013. In the meantime Citizen Koch premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2013, but a few months later, in April, ITVS decided to back out of support for the film. Lessin and Deal were on their own as far as finishing and distributing the film was concerned.

In a statement at the time, ITVS claimed that the withdrawal was based on editorial differences. Lessin and Deal are firm on the stance that their film was dropped because David Koch serves as a trustee of PBS station WGBH in Boston. Their decision to regroup and put Citizen Koch on track again, however, was clear. "ITVS reneged on our funding agreement and broadcast partnership because WNET was cultivating a seven-figure donation from David Koch," Lessin asserts. "That left us with a $150,000 funding gap and massive debts, just as our big-ticket finishing costs were coming due. Nearly 3,500 small-dollar donors across the country stepped up and made their voices heard through a Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign. Many of our backers told us they were public television viewers who felt betrayed by the actions of ITVS."

Lessin and Deal make it clear that they care about their film's fate, but also about their "documentary profession and the integrity of public media." They took their story to Mayer at The New Yorker and gave her records of conversations in which ITVS officials were flatly against the new title and evolving focus of the film. Mayer reported that the combination of pressure from WNET and the fear of PBS finding itself embroiled in a scandal prompted ITVS to terminate the progressively rocky relationship with Citizen Koch. Mayer also claims that in the absence of federal funding for public broadcasting, affiliates such as WNET are dependent on wealthy patrons for support. (For the complete New Yorker article, which was published in May 2013, click here.)

But Lessin and Deal are far from being out of luck. They say they have been embraced by the independent film community, and by the largesse of strangers and colleagues alike. Their crowdfunding campaign certainly testifies to the same, coming in at a current figure of $169,522. "Friends, colleagues and our many institutional partners shared the campaign with their networks, and we reached out to everyone we had ever met, and the campaign gained momentum," Deal recalls. "We initially were seeking half of the lost funds but were astonished at the outpouring of support, and we ended up meeting our initial funding goal in three days, and then doubling that within 30 days. Along the way, we received guidance and moral support from the folks at Kickstarter, from other filmmakers successfully crowdfunded, from funders like Creative Capital, and from Sundance Artists Services."

The journey has certainly been a challenging one, perhaps the hardest one for any documentary filmmaker to take. Public broadcast remains the lottery for documentary film. "Citizen Koch lost the largest viewing audience in the country for documentary films," Lessin maintains. "But we didn't have to compromise the editorial integrity of the film in order to placate David Koch. We spurred a conversation about the influence of high-dollar donors and conservative operatives on public television, underscoring the importance of public financing for public media. We spoke out because we want things to change; we want our revered public institutions to operate free from this type of political pressure. Any progress in that direction is a silver lining."

The film moves steadily ahead, and while not shy about their losses, Deal and Lessin are optimistic about the road ahead. "In addition to becoming experts in self-distribution and funding, we've also partnered with independent distributor Variance Films, who brings the creativity and expertise to the Citizen Koch release as it has with releases by Spike Lee, John Sayles and most recently Dave Grohl," Lessin explains. "Variance is doing more than booking theaters; the team there is providing in-house marketing, group sales, social media management, promotions and materials coordination." On the possibility of any further political backlash, they are not so sure. "Only time will tell," says Deal. To other documentary filmmakers, he warns, "Work collaboratively, transparently and in integrity. And before you begin, make sure there are no financial conflicts of interest involving your subjects and your distributor."

Lessin and Deal state that their film is about "the 1 percent" versus "the rest of us." On reworking the film in the context of the constantly shifting tides of its subject matter, they say that "dealing with material that is so of the moment, we had to make a few factual updates—such as the Kochs' net worth. When we began, they were worth $50 billion dollars collectively, then $68 billion, and by the time we made our DCP, it was up to $100 billion. A month later, they are up to $105 billion, but the film is, as they say, in the can."

Lessin and Deal have done more than picked up the pieces and started over without the prestigious PBS by their side. "Citizen Koch will have screened in more than 150 theaters across the country by summer's end," says Lessin. "That has exceeded our expectations for the theatrical run already. We hope that audiences will continue to be moved to dialogue and to action. And we hope that groups in the money and politics, environmental, labor, corporate accountability and voter engagement movements will continue to use Citizen Koch to reach new audiences and engage more Americans in the battle to reclaim our democracy."

Deal adds, "Hopefully the takeaway for public television executives is, Don't mess with the public trust. When they allow private interests to influence programming and funding decisions, the public will take notice and take action."

Citizen Koch, which opened June 6 in New York, opens June 27 in Los Angeles and other cities, and will roll out across the country through the summer. For more information, click here.

Nayantara Roy is a journalist and documentary filmmaker who will begin pursuing a business degree this fall, at Columbia University.

From Joshua Oppenheimer's The Act of Killing. Courtesy of Drafthouse Films

Editor's Note: While the title of the film that we discuss here is The Act of Killing, the header of the article is intentionally "The Art of 'Killing'..."The quotes around "Killing" refer to the film itself, while "Art" comments on what's discussed in the article—that the killers not only took up the filmmakers' suggestion that they re-enact their atrocities for the camera, but they doubled-down on that suggestion and created a full-fledged theatrical and cinematic extravaganza, thus sensationalizing their crimes as art. What's more, as killers, they took their cues from another art form: Hollywood cinema.

Before he made his film The Act of Killing, Joshua Oppenheimer interviewed survivors of Indonesia's bloody "Transition"—the failed military coup of 1965 and the brutal anti-Communist purges that followed—for an exposé on their culture of fear. Police shut down each meeting.

With fear of reprisals, Oppenheimer asked the survivors if they should stop filming. The survivors opposed unanimously, but volunteered a solution: Film the killers, and the police won't stop you. "Begin with my next-door neighbor, the man who killed my aunt," one survivor suggested. "He will appear to be proud. Film that and the audience will see why we are afraid."

After the failed coup, the Indonesian Army began a campaign of political apartheid. They paid street thugs and gangsters to rid the country of the National Communist Party (PKI), whom they blamed for the coup. There were no official trials to prove political affiliations, just semi-private assassinations.

The men who carried out the killings have been glorified in national media as heroes. Even today, they appear on talk shows, have political influence, and boast loudly about their murders to anyone who'll hear—including the families of the nameless victims they left on riverbanks and in ditches five decades ago. The most commonly cited death toll is 500,000, but accurate numbers are hard to tally. It's impossible to say the campaign has ended, since the political class that sanctioned it did so to gain power. And both power and its attainment are limitless things. Corruption persists in Indonesia.

In February 2004, Oppenheimer filmed two killers who took him to a river. During the Transition, these two men would drive a busload of internees from the military concentration camp to a riverbank every night, behead the passengers and throw the bodies in the water. "After they showed us how they'd done it, one of them took a small camera out of his pocket and asked my sound man, ‘Would you mind taking a picture of us to remember this day?' and the two posed, giving the thumbs up and "V" for victory. I went home with that material thinking, I have to make a film that adequately attempts to understand this."

Errol Morris, an executive producer on The Act of Killing, made his 2008 documentary Standard Operating Procedure in response to the photos depicting the torture and humiliation of detainees at Abu Ghraib prison. He viewed those images with an exposé quality. "Standard Operating Procedure evidences a moment in which people want to remember themselves while torturing someone," says Oppenheimer. "Errol saw the pictures as confessions of a whistleblower. The Act of Killing is an attempt to understand an entire regime that did something similar; it wasn't just one person."

Oppenheimer spoke to 41 perpetrators and took each of them to the scene of their murders to act out what they'd done. With cameras rolling, they'd lament, "Oh, I should have brought a machete, and friends to play victims." But Anwar, one of the subjects in The Act of Killing, was the only man who returned to the roof where he'd killed hundreds, and neither lamented nor wished for co-conspirators. Instead, he danced. "Unlike the other 40 perpetrators, his pain was somehow close to the surface," Oppenheimer observes. "When he goes out on the roof, he sighs; it's like there's a stone in his shoe. He says, ‘I dance to forget these horrors, and so I'm a good dancer.' And I'm wondering how this must look to him."

These killers are a vainglorious bunch. Anwar's hair is dyed black, his attire is carefully chosen, his company is conspicuous; he is a celebrity war criminal. For five decades, Anwar has suppressed his conscience and any urge to conceal his part in the murders—the shame typically associated with crime is in conflict with the state media's celebration. Demonstrating a feeling other than pride would suggest he wasn't on the national bandwagon. And anyway, who says he wants to demur? He loves the attention.

As The Act of Killing ultimately reveals, Anwar's humanity is his liberator and his punisher, but that denouement entails a lot of excavation. What Oppenheimer cannot do is discuss the murders in a critical tone, lest he risk looking like an objector—which means there's more at stake than Anwar's ego.

Fearing Anwar would see the footage of him on the roof and call the shooting off (or worse), Oppenheimer assigned a production manager to stand by at the Jakarta airport with money and the crew's luggage, in case the filmmaking team had to make a quick getaway. Oppenheimer says it was the only time in the process he felt genuinely afraid. "Anwar watched the footage of himself and was disturbed, still not acknowledging what this means," the filmmaker recalls. "To admit it looks bad is to admit it was bad, and he's never been forced to do that. So he displaces the discomfort onto his clothes, and his acting. I realized that if I gave [the perpetrators] a way to act it out, to dramatize it in whatever way they wish, and I filmed the process and combined it with the re-enactments, we could create a kind of documentary of the imagination, rather that a documentary of their everyday lives, that allows me to see how they live with what they did and how they want the society and the world to see them."

Anwar invites Ari, an old partner in crime, to film his scenes with him. Ari has been living abroad with his wife and teenage daughter, and unlike the other perpetrators we hear from, he's got a more sanguine, worldly view. Perverting Napoleon, he says, "War crimes are written by the victors." The last thing you expect from anyone in this story of state-sanctioned slaughter is moral relativism, but he continues: "Killing is the worst thing you can do. If you're paid for it, do it. You just need a good excuse."

"Their government provides the excuse and they cling to it because it allows them to live with what they've done," Oppenheimer notes. "The justification of genocide is celebration, especially when they're insecure about what they've done. The irony is that the boasting—which I saw as a symptom of impunity—was in fact a sign of humanity."

All of this suggests these men have been "acting" for some time. So then why give them high-class art therapy? The perpetrators have a national media boosting their violence as liberation; they have TV talk shows applauding their war crimes; they hold high-ranking offices and live like glitterati. How much more privilege can they enjoy? Is The Act of Killing trying to dole out punishment or reward?

"There is no catharsis," Oppenheimer explains. In one of Anwar's scenes, he plays the victim. "I understood instinctively that the dramatization of the killings was a kind of running away," Oppenheimer maintains. "They would never dramatize it if they understood it was crime. It was almost an anti-therapeutic process. If I'd been looking for Anwar's catharsis, I would have heard him say, ‘I feel what my victims felt' and [I would have] said ‘Yes!' and it would have been sentimental." But that's not what Oppenheimer did: "No, you don't feel what they felt. They believed they were going to die," he says. The moment is as close to punishment as we see, and yet provides little resolution. What Oppenheimer understood when he was filming this scene was that we might want to pelt Anwar with stones but it wouldn't get us anywhere.

"These men escaped justice but not punishment," Oppenheimer maintains. "That final picture of Ari staring into the mirror—that emptiness is a kind of damnation. It's an emptiness that's there from the beginning. Ari enters saying, ‘What we did was wrong and I know it.'" It's as if Oppenheimer is reminding us why Alain Resnais made Night and Fog, one of the earliest documentaries about the Holocaust: There is no bottom to this; it is unquantifiable.

The footage that frames The Act of Killing is a high-gloss song-and-dance around a waterfall. Girls sway in dreamy light, and chained zombies thank Anwar for killing them. "Anwar came up with the waterfall dance right after playing the victim, and I think as a response to it." Oppenheimer explains. "It feels like a desperate act to put this right. He thinks it's beautiful but it's a lie, because it can't be beautiful and true at the same time."

The Act of Killing opens July 19 through Drafthouse Films.

Sara Vizcarrando is editrix of the release calendar at Rotten Tomatoes; a film studies instructor; and a blogger for http://movieswithbutter.

Seven Years, '5 Broken Cameras': Documenting the Occupation

By Tom White

Editor's Note: 5 Broken Cameras airs August 26 on PBS' POV, then will stream on POV's website August 27-September 25. What follows is an interview we conducted with filmmakers Guy Davidi and Emad Burnat following the film's nomination for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

5 Broken Cameras, nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, gives viewers a riveting, ground-level perspective on the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and the nonviolent resistance movement against the settlements that began in 2005 in the West Bank village of Bil'in. Emad Burnat, an olive farmer who quickly caught to the power of the camera as a documenter, witness and protector, captured seven years in the life of his village, filming demonstrations, arrests and killings, while preserving the personal memories of his son Gabreel growing up amid the conflict and his wife Soriah holding the household together while imploring Burnat to stop filming. The five cameras he deploys, all broken while filming confrontations with Israeli soldiers, capture Burnat's transformation to journalist and documentary filmmaker.

Israeli activist and filmmaker Guy Davidi, the co-director, co-editor, writer and co-producer of 5 Broken Cameras, had spent a long period of time in Bel'in prior to meeting Burnat, both making films and getting to know the residents there. He worked with Burnat to find and shape the story, turning it into a personal tale of struggle and empowerment.

Documentary.org spoke with the filmmakers by phone, separately—Davidi in New York, and Burnat, the co-director, co-producer and cinematographer of 5 Broken Cameras, in Bil'in. These interviews have been condensed and edited.

Documentary.org: How did you and Emad Burnat meet? How did start working together on 5 Broken Cameras?

Guy Davidi: I was an activist going to different villages on the West Bank, starting in 2003. As a filmmaker I was covering a lot of issues and doing some videos for the Internet, and a lot of camera work for other filmmakers who were interested in different issues. In 2005, when the movement reached Bil'in, I went there along with other Israeli activists, first of all to support the people. But since I'm a filmmaker, I was starting to think about how to present on film what was going on there.

What was striking at first was there were a lot of people filming everything, especially the demonstrations, so I didn't feel I had a space to work on that issue. So with a Swiss named Alexander Gutchman, we started to work on finding new angles and new points of view that were related to the occupation. My first short documentary was In Working Progress and from that film we went to the construction of the settlements on the land of Bil'in and filmed construction workers, who were Palestinians. We saw the contradiction: The team that was building the settlement was also going to the demonstrations and protesting against the construction.

For [my next film] Interrupted Streams, Alex and I wanted to do something that would enter more into the lives of the people, and deal with much more internal and transparent influences of the occupation. Water seemed like a good metaphor of how occupation penetrates every aspect of your daily life, so for that film I stayed with Alex for more than two months in Bil'in. For that period of time I had a lot of talks with a lot of people about their childhood, their dreams, their expectations of life and how they can plan their lives, where occupation can always take you by surprise. So a lot of these talks inspired me later on to write the narration for 5 Broken Cameras, and they were a source for working together with Emad.

I stayed there a long period of time and that was the first time that an Israeli wanted to live in the village and not just come to the demonstration. But I was very much accepted and I think later on it also helped to have people from the village trust me because I had shown commitment to what was happening.

Emad was filming at the same time. In the first years he was filming I don't think he had watched a documentary before seeing other filmmakers come in and make films about the nonviolent movement. There was one film, Bil'in My Love, that was released in 2006. The director, an Israeli named Shai Carmeli-Pollak, was working a lot with Emad, and he gave him an idea that he should make a film one day.

We knew each other because everybody knew Emad. He had been filming for years. He filmed as an activist, and he posted his videos on YouTube and gave his footage to a lawyer to use as proof and as a way to protect the people, and then later on he started to give this footage to news agencies and channels and that way he started to work with Reuters as a freelance cameraman. But I think later on he got this idea to make a film and he started focusing on Adeed [a friend of Emad].

The problem was that Shai had covered this story with Bil'in My Love, which was an international success. When Emad called me in 2009 it was through an organization called Greenhouse, a fund film development project. With a friend of ours, Emad applied to Greenhouse to help him shape the film. In 2009 [Emad's friend] Phil died, and the idea was to create a film around Adeed and Phil and use some footage that he had of Phil. It was supposed to commemorate him, but it didn't really work out because the submission was very ideological and the producer left the project. Emad needed someone to work with, so, with Greenhouse, he gave my name. They called me trying to convince me to join the project. And I didn't want to because, first of all, most of the film would be Emad's footage, and without knowing it I imagined that he would have a lot of demonstrations, a lot of direct action and it would be his version of Bil'in My Love—kind of an activist film., which was not interesting for me.

Second, I didn't see why I should be aboard because I'm not a producer. I'm a filmmaker and a writer. I didn't think there was a space for me there.

Third, it's very difficult to create a film together with a Palestinian. It's not just because of how we both will be judged, but I will always be in a difficult position because I will always be on the Israeli side. My role will never be understood. Being a Palestinian is a very comfortable position in some cases. Of course it's his footage and obviously it will be a very difficult personal decision, and we'll be judged by our people around us. He will be judged for choosing to work with me and I'll be judged for choosing to work with him, so it's a very difficult issue.

But I told myself, Maybe...I knew everything that Emad had done in his life. I knew he had had an accident, I knew he had been arrested, I knew that he had lost cameras. I told myself, If you're able to tell a story from his personal perspective, he will be the center of the film, you'll use him as a character and you'll create a voiceover for him, it'll be a nice opportunity—important politically because I'll be empowering his voice, which personally again it'll be a difficult thing to do, but politically it will be meaningful. I'll be there to encourage his voice and not put my voice in it—create something balanced— which is something I wasn't sure politically was the right thing to do, but to be able to see the intimacy of life through his eyes would be something that might be very emotional, very strong.

So when I went to meet him for the first time, to see his footage, my idea was to see how can we link all these events that had happened within his own personal life. I know that Adeed and Phil were his friends, and I knew of the stories of his brothers which were important in the movement, but I didn't know anything else.

So the first idea was to make a film about Adeed and two friends—the story of three friends. Then later on I saw this footage of an old man blocking a jeep from taking someone to prison. I asked Emad, "Who is this guy?" And he told me, "That's my father and he's blocking the jeep from taking my brother to prison." I imagined how he would feel in that situation, at that moment, making the decision to film and not to do anything else. Suddenly he became a son and not just a cameraman. When I tried to see if he was willing to make a film about himself, he was open to that, so I offered him, "Make a film about yourself; put yourself in the center." And it was not an easy decision. He would be judged: Why are you taking all the Palestinian village story to tell your story? But at the same time he was also flattered, so he accepted it.

Then, we looked at more footage. I discovered that Gabreel [Emad's son] was born a week before the start of the demonstrations in Bil'in. I told Emad, "This is important. This is your son; we can use him to create a line."

A lot of footage was filmed once I joined the project, so from 2009 to 2011 Emad was filming with a different approach because once he decided to create the film that way, we still needed a lot of footage that would create links between the personal elements and the social elements, so you had scenes like Emad's wife asking him to stop filming, and when he takes Gabreel to the demonstration and when you see Emad's wife putting Gabreel to sleep—a lot of these scenes were filmed after I joined the project. Emad was trying to get this footage very fast so he would be able to create this line that was not originally planned.

D: As director focusing on this period—2009-2011—how often did you visit Bil'in? What was your role from this point forward?

GD: When I got into the project, it had hundreds of hours of footage by Emad, hundreds more hours by other cameramen, and there was no story and there was no clarity about where the film was going to go, other than the fact that Phil was supposed to be in it and the nonviolent movement as well. So I created the narrative line—the 5 Broken Cameras line, the concept of it and Gabreel as a character, Soriah as a character, Emad as a character, and then I wrote the narration. We had conversations every week. I went to Emad and we shot and we discussed the text; we went for three weeks and we reviewed footage. And then every week we came to Bil'in and Emad gave me footage. We brainstormed together about what kind of scenes to film. We always made sure that whenever I'm not needed, Emad will be filming; I'm not going to be there, unless it's Emad himself who is filmed, like when he presents the five broken cameras or the hospital scene; in those cases I'm filming him. I was constructing the film for Emad. It was his life, and the way he speaks about it is, This is his life, this is his experience.

It was a lot of collaborative work, not just by myself, but with a lot of people with the Greenhouse team. Later on when we started to work with Véronique Lagoarde-Ségot, the editor, she was doing magic with the footage. I was able to create the structure of the film, but I wasn't able to make the story easy to digest in a way that every international viewer would understand exactly what is going on, then could experience the feelings. But that's something that Veronique brought. There was also a lot of repetition in the story, because occupation is repetitive. This gets you out of the story because you feel this is endless; Veronique gave the film a sense of development.

D: I wanted to talk a bit more about Greenhouse. How did they become involved in the film?

GD: Greenhouse is a Mediterranean development project. It was initiated by the Israeli Cinema Fund, but it's not sponsored by Israel because the idea is to bring filmmakers from different countries, from Arab countries and from Israel and from Turkey to seminars together with European and American and Western professionals who are doing mentoring for projects that are dealing with different issues.

I joined the project once Greenhouse was already aboard. They had an important role in creating the trust between [Emad and me]. They were also helping us with promotion and finding investors.

At the same time Greenhouse was sometimes not accepted by some Arab countries and Arab filmmakers because of the boycott and because of a lot of political issues. For us it was clear that the film was much more important than these issues. There's Israeli involvement, even though it's not governmental.

D: Tell me about how you secured funding.

GD: The first funding was American: ITVS International's development fund. Then we got Dutch funding, then the Israeli Cinema Fund was the most important money at the beginning. In 2011 we managed to get French TV on board, and they helped us with much more money, which allowed us to edit in Paris and work with Veronique.

Interview with Emad Burnat

D: 5 Broken Cameras is both your personal story and the story of the life of Bil'in over seven years. At what point did you and Guy determine that your personal story would be an important part of 5 Broken Cameras?

Emad Burnat: In 2005 when the people of my village started the protests and the demonstration, I decided to take my camera and go out, for different purposes: to protect myself and the people around me, and to be a witness with my camera and use the footage for websites or YouTube or for other journalists. The village became stronger and the nonviolent movement became stronger, and people came to give support. Even Israeli activists came to my village, and people came to study the nonviolent movement. Other people came to make documentaries; they asked me to give them footage because I was the only cameraman in the village, documenting the daily life.

The idea of making this documentary came to me from one of my friends. He asked me, "Why don't you make your own film? This is your story." So I thought, Yes, this is my story; I was affected by this. My son and my friends had been affected by this. So I started following and focusing more on my friends and on my son Gabreel growing up, and working on the story. That story was there and the idea was there, so I proposed to Guy Davidi after five years of working on this film to join the project, but not to make it an Israeli-Palestinian collaboration. He was an Israeli activist also, so I proposed him to join us to support me in making this Palestinian documentary.

So he gave me ideas on the production. And then so many ideas came from friends, from outside for the creative development and the construction of the film in a way for Western people to better understand the story, the situation and the subject. So it's my story, my point of view and my personal perspective about the daily lives and my son growing up.

D: Throughout the film, you as the narrator say some very interesting things about filmmaking. At the beginning of the film, you say you film to hold onto your memories, and by the end of the film you take us to a deeper place: Filmmaking is a means of healing, of confronting life, of survival. It's been over a year since you premiered the film. What is filmmaking to you now that adds to what you articulate in the film?

EB: I think first of all, it's about the creative process of this film: When you put all of this together--the art and the idea and the feeling, and the relation to the place and the daily lives—you make a strong piece of art. This happened with me and my village during the last seven years when I was making this film.

The film got a good reaction and made a very strong impact around the world, so I think that when people watch this film, they understand more and are more touched by the story because it's through my story, through my life, and they feel they are inside the lives. It's not just a film; it's something about life. There are many films about this subject, but most of them were made by people who came from outside. They really didn't live the reality; they didn't suffer; they didn't feel the same feeling that people who live there feel. When I narrate, it comes from inside, from my feelings. It's not just a talk or a conversation. So you feel that; this is what it's like to be there, in that situation.

D: You are both a journalist and a documentary filmmaker. A lot of documentary makers come from both print and broadcast journalism. What to you are some of the similarities between journalism and documentary filmmaking, and what are the differences?

EB: For me, to make this documentary—first of all, it's my life, it's my story, it's my issue. In journalism they have part of the story; I was working as a journalist getting footage for TV channels and how that affects the journalism and affects people who have cameras. But for me, I live close to the subject, what happens in my village and what happens to my people. So it was related to me in the village—my friends, my village and the situation in the land-to mix that with art and filmmaking and the editing, this was important for me. It was not just to make a film. I know many people who are filmmakers; they just go and shoot some shots and they get footage and they make films. That's not my position. My position is to make my film related to me and related to my situation. For me, it's not about the business; it's not about making my films famous. It's more important for me what happens in my village and what's my message, so my goal is to reach people around the world. This is what's important for me about making films.

D: Talking about reaching people, I know you've shown this film in Israel at the Jerusalem Film Festival. What has been the audience reaction among Israelis?

EB: In Israel, the film had a very good reaction from the Israel society, but at the same time there have been many bad reactions from many people in Israel about the film and about the story. But I think it's making some change with the Israeli people and the Jewish people in the United States and other places.

The film was shown in Palestine also. The people know more about this; they related to the place and they related to the situation. This is how the life is in many parts. They were more touched by the story, to see the village to remind them what happened before for the last seven years. So it's very touching to watch this.