At the heart of Jeonju lies the Jeonju Film Street, an aptly named stretch lined with five multiplexes, whose surrounding alleys are dotted with cafés and bookstores adorned with film-themed decor, selling posters, books, and other cinematic paraphernalia. Each year in early May, some 20 halls across these venues host simultaneous screenings back to back for 10 days as part of the Jeonju International Film Festival. South Korea’s second most significant film event after the Busan International Film Festival, Jeonju draws tens of thousands of cinephiles from not only across the country but also around the wider region who come eager to discover new films and savor Jeonju’s signature dish, bibimbap, proudly served in its hometown.

Since its inaugural edition in 2000, Jeonju has been carving out a distinctive niche, particularly in Asia, through its bold programming that champions alternative, experimental, and independent cinema. The 26th edition this year screened 224 films from 57 countries, including 98 Korean titles. Nonfiction cinema has been a crucial component since the beginning. One-third of the 662 submissions to this year’s International Competition were documentaries. While other sections had many more nonfiction offerings, it is worth noting that two of the International Competition’s three prizes went to documentaries: Chinese filmmaker Deming Chen took home the Best Picture Prize for his second feature Always (following its win at CPH:DOX, which is covered elsewhere in this issue), while the Spanish-Portuguese co-production Resistance Reels by Alejandro Alvarado Jódar and Concha Barquero Artés won the Special Jury Prize.

Alongside the film screenings, Jeonju boasts abundant side events, such as talks, exhibitions, and even busking performances in nontheatrical venues, some of which continue beyond the festival period and run throughout the summer. The most iconic among them is the 100 Films 100 Posters exhibition, currently in its 11th iteration, which showcases 100 films from the festival lineup through posters made by 100 graphic designers. In addition to its cinephile chops, the festival’s progressive sociopolitical consciousness and commitment are also reflected in its program. Responding to the ongoing crisis of democracy that South Korea is facing since the now impeached ex-president Yoon Suk-yeol declared martial law on December 3, the festival presented a special section called “Again, Towards Democracy,” which comprised six documentaries exploring political turmoil around the world, including Sudan, Remember Us and The Last Republican. It’s likely that next year’s edition will feature local films directly addressing the current political upheaval.

Korean nonfiction cinema has a strong presence at Jeonju every year, and this edition was no exception. Last year, the festival showcased several critical documentaries in commemoration of the 2014 Sewol Ferry disaster, where government inaction and media cover-ups led to the death of over 300 people, most of whom were high school students. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Korean Liberation, and the festival featured three feature documentaries examining the thorny identity struggles of Zainichi Koreans: ethnic Koreans who remained in Japan during and after the colonial period and their descendants, and who often find it difficult to feel at home in both Japan and South Korea.

Horoomon.

Of these, the most well-realized was Lee Ilha’s Horoomon. Like its workhorse title—horoomon is Japanese for “grilled offal,” a dish that’s mentioned in passing reference to colonial-era prejudice against Koreans who ate it—the film is an engaging, if formally monotonous portrait of third-generation Korean-Japanese activist and businesswoman Shin Sugok, structured around her decades-long legal battle against Japan’s far right and their anti-Korean hate speech. One of the most in-demand titles at the festival, Horoomon was notably the only Jeonju Cinema Project that screened this year.

Since the festival’s first edition, this flagship initiative has been directly funding the production of Korean and international low-budget independent films, with the completed works—usually three to four features (omnibus shorts prior to 2015)–premiering at Jeonju the following year. Some past winners from recent editions include critically acclaimed works such as Direct Action (2024) and Samsara (2023). That only one film was completed and screened this year may be a troubling indicator of how costly and time consuming even independent film production has become. Sung Moon, one of the festival programmers, mentions in a festival publication how “an increasing number of emerging directors [are] spending considerable time seeking supplementary funding even after receiving [the Jeonju Cinema Project] funding of KRW 100 million [about 73 thousand USD].”

Jeonju Film Street.

Colorless, Oderless

This year’s Korean Competition included just one documentary, Lee Eunhee’s debut feature Colorless, Odorless, a standout among the local documentaries for both its subject matter and formal approach. The film lays bare the serious health hazards faced by the predominantly female workforce of South Korean and Taiwanese semiconductor and display factories, whose main customers are Samsung, Apple, and Asus. Lee follows past and present workers-turned-activists unionizing and demanding postindustrial medical care and benefits after being diagnosed with leukemia and other occupational diseases or giving birth to children with disabilities and developmental delays. But theirs proves to be an uphill battle. In interviews, the activists explain how the legal system often protects corporate interests in the name of safeguarding trade secrets, concealing many details of the work-related illnesses and incidents from the public. With the deck stacked against them as such, the ill bodies of the workers themselves become the only visible evidence of the hazardous working environment in which the dust suits they wore were designed to protect not them, but the products.

The colorless and odorless carcinogenic chemicals that evade the naked eye and the camera are viscerally evoked through animated liquid substances paired with ominous static noise. Lee noted during the post-screening Q&A that getting access to film inside such factories has become impossible. To make up for it, she repurposes grainy black-and-white footage from previous documentaries and inserts a surreal AI-generated sequence (created using Runway Gen-3) depicting an assembly line of workers wearing stethoscopes. This latter choice felt at odds with the film’s grounded and urgent subject matter, particularly so when Lee also makes a point of mentioning how 32 liters of water are needed to make a single semiconductor.

By contrast, the more conventional talking-head interviews proved far more effective and impactful, allowing the workers to speak for themselves. In one emotional scene that brought much of the audience in my screening to tears, a former Samsung Electronics worker recalls the pride she once felt working for a company seen as a symbol of Korea’s economic miracle, only to now rhetorically question whether her employer knew the toxic conditions of the so-called “clean rooms.” In another, an activist calls out Samsung’s relocation of some operations to Vietnam as a cost-cutting move, not a solution, driven by low wages and environmental, health, and safety costs in the Southeast Asian country. In just 55 minutes, Colorless, Odorless manages to develop a searing indictment of how science and industry often become complicit in a neoliberal economic system that routinely sacrifices human lives for corporate profit.

If I Fall, Don’t Pick Me Up

If I Fall, Don’t Pick Me Up

One of the most distinctive sections of this edition was Possible Cinemas. Unlike the Expanded Cinema section, which highlights formal experimentation, Possible Cinemas focused more on the ethos of independence. According to the festival publication of the same title, the section was born out of a soul-searching for Jeonju’s identity and inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s quote in Wim Wenders’s 1982 documentary Room 666: “Cinema was born with small movies.”

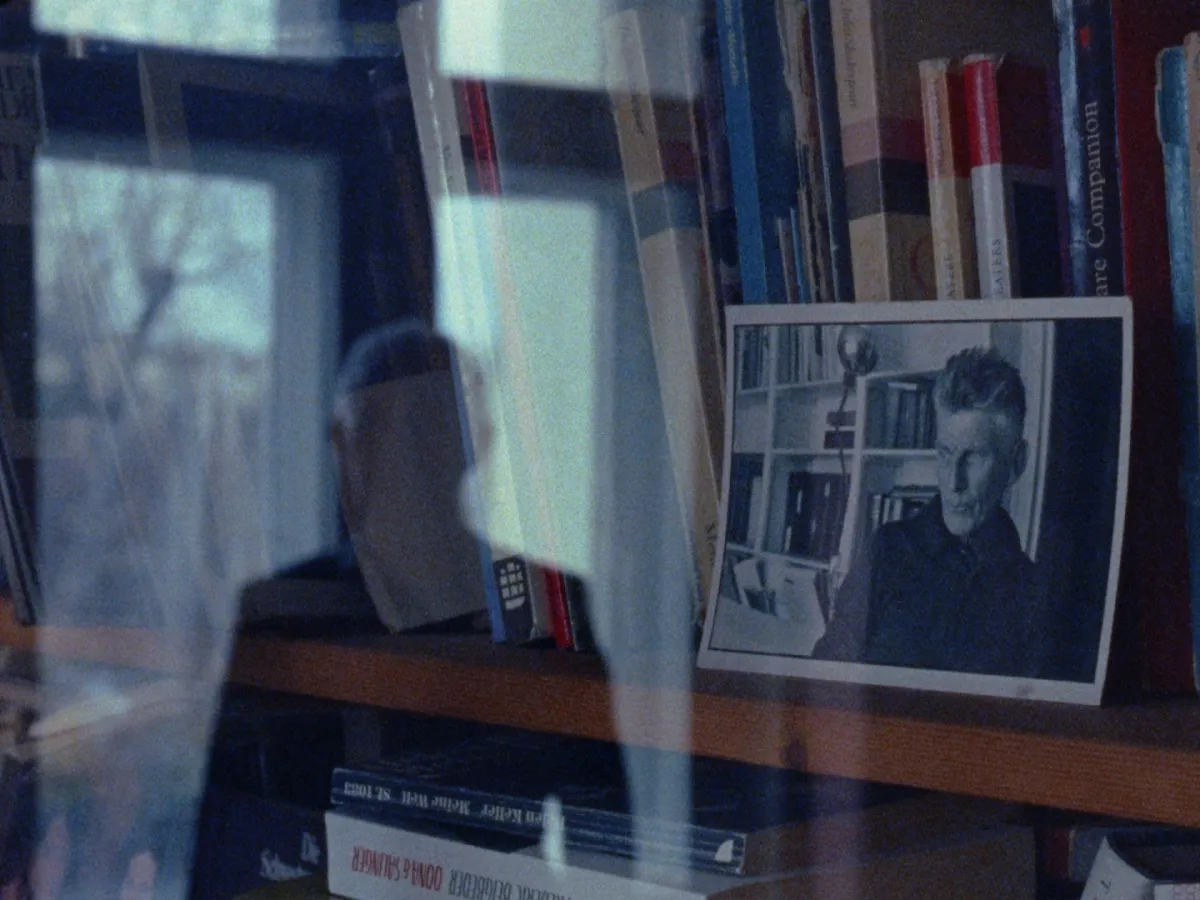

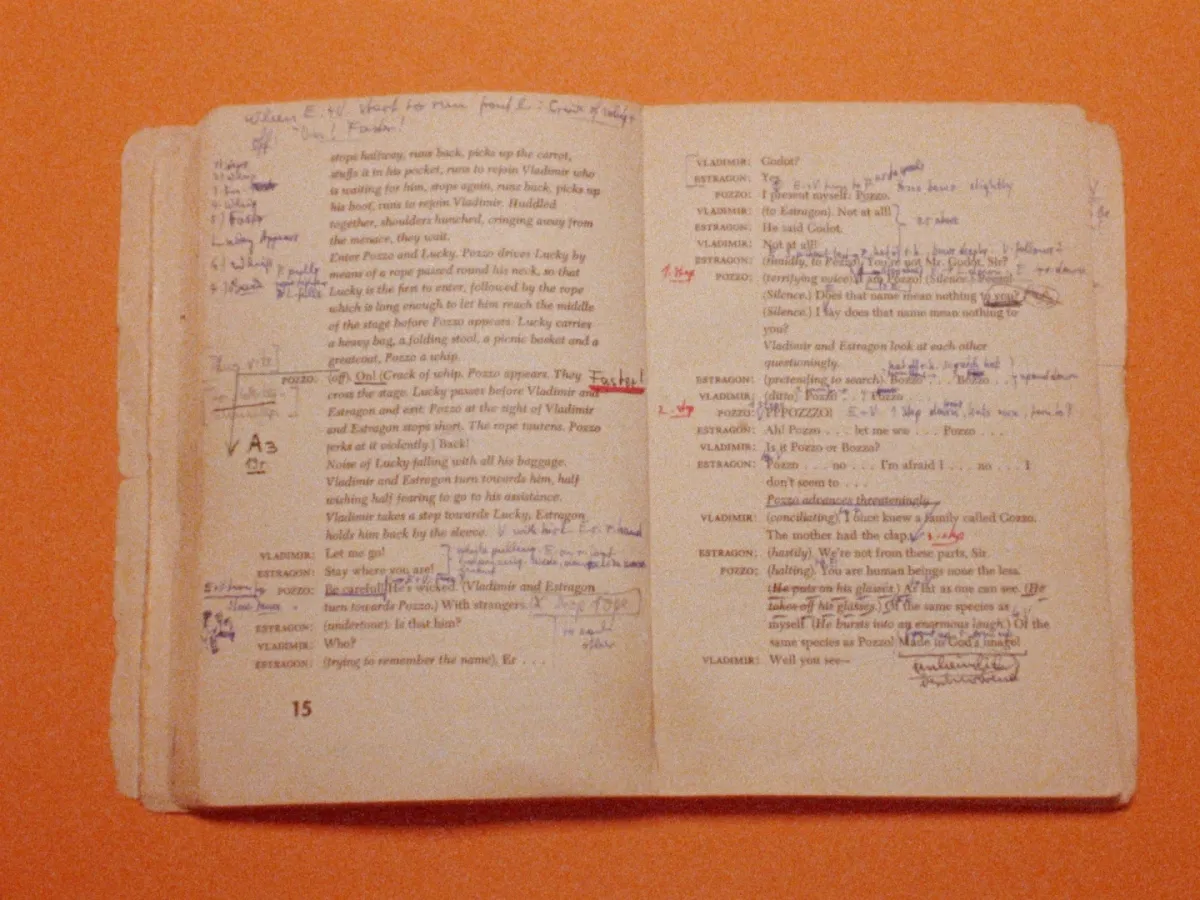

One such “small” production is If I Fall, Don’t Pick Me Up by Irish filmmaker and artist Declan Clarke. A quietly beguiling work, the film takes its time to draw viewers into its subject: the working relationship and friendship between the Irish writer Samuel Beckett and the German theater director Walter Asmus. The two first met in the early 1970s and collaborated closely until Beckett’s death in 1989 (his final literary work, the poem “What is the Word,” is dedicated to Asmus). Clarke’s film succeeds in part because it doesn’t try to tell Beckett’s life story in a single film (perhaps an absurdly impossible effort anyway). By zeroing in on just one relationship instead, the film allows glimpses into Beckett’s character through his correspondence with Asmus, whose directorial work played a huge role in Beckett’s international success. The details become obvious, such as the playwright’s subtle change of tempers in the letter sign-offs: when Asmus says he’s unavailable to meet him, Beckett’s casual “Sam” becomes a more formal “Best, Sam Beckett.”

The formal aspects of the film also reflect this subtle simplicity. Clarke at first relays much of his research on the two figures through long texts on screen with solid-colored backgrounds, later showcasing the archival sources that Asmus provided—photographs, playbills, postcards, and letters—and reading their content aloud himself. Shot on film, the film is visually spare; it favors still, contemplative compositions of buildings, staircases, and public parks, all devoid of camera movement and accompanied only by ambient sound. The imagery changes toward the end of the film from urban environment to rolling hills and open grasslands with a solitary tree—a clear visual echo of Waiting for Godot. Nearly every frame could pass for editorial photography, and the stillness invites a heightened awareness of time’s passage and of the minute, evocative details within the composition. The film’s most emotional moments come when Asmus appears on screen, staring into the distance, standing alone on a minimalist set of a Godot production, doing nothing except perhaps reminiscing about his late friend. Clarke’s approach is to keep things simple and the result yields a film as stripped-down and meditative as Beckett’s own plays.

Another work that experimented with a different form of adaptation was Resistance Reels by Alejandro Alvarado Jódar and Concha Barquero Artés. The documentary’s starting point is the ghost of films that the Spanish director Fernando Ruiz Vergara never made. During his short-lived filmmaking career, he only completed one film—the 1980 documentary Rocío that exposed the perpetrators of fascist crimes following the Spanish coup of July 1936. Banned by Spanish authorities, the uncensored version cannot be shown in the country to this day. He fled to Portugal and was in contact with Alvarado and Barquero in his late years. When Ruiz passed away, the creative duo decided to take up the mantle and make the films that he never got the chance to make.

“This will be a rebellious film,” the directors declare via voiceover early in the film, followed by silent clips from what seem to be the parts of Rocío that were censored by court order. The centerpiece of the film consists of a quartet of short films that Alvarado and Barquero made using the archival notes and unfilmed scripts that Ruiz Vergara left behind. These short segments span a wide thematic range, from Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho’s run for Portuguese presidency in 1976 and land reform in Andalusia to the history of the Festival of Militant Cinema in Spain and the working conditions at the massive Panasqueira mine in Portugal. The strong point of Resistance Reels, however, is not so much what these stories are as how creatively they are presented. Despite a somewhat hectic pace and abrupt transitions, the co-directors engage audiences through intimate voiceover narration—often whispered direct addresses—adding a more participatory element to its storytelling. In the last two segments, scenes of mining and archeological excavation serve as resonant metaphors for the documentary’s own process—a cinematic unearthing of buried and forgotten stories. In this way, Resistance Reels fights against artistic censorship and offers us possible cinemas that otherwise would not have existed.

Resistance Reels

Resistance Reels