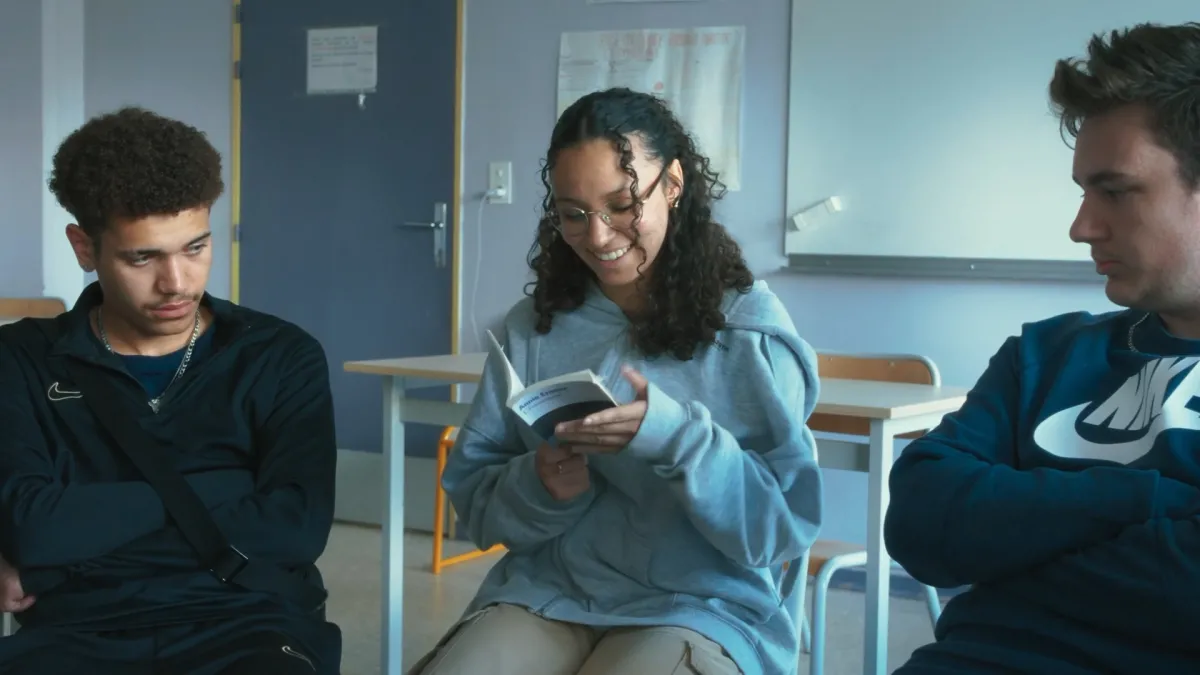

This year’s Venice film festival had its share of fiction features guaranteed to fray nerves, whether because of an incoming nuclear missile in A House of Dynamite or conspiracy-fueled kidnapping in Bugonia. Perhaps that’s why Claire Simon’s Writing Life arrived as such a balm, with its articulate teenagers discussing (and at times cordially disagreeing over) the work of Annie Ernaux. The author’s fine-grained fidelity to describing the banal and the taboo energizes these small groups and yields up a vision of literature bettering lives through the solace and strength of seeing personal experiences voiced in a down-to-earth way that makes no excuses—what Ernaux called “flat writing” in her Nobel Prize acceptance speech. Simon remains a pastmaster of filming young people in schools (here several lycees in France) and gets the drama coursing within their dialogues, and she makes a point of showing them chatting outside, at a beach or under a tree, watching their ideas take life and flight (and so not feel like a school assignment). She ends with an incredible sketch of a possible Ernaux of the future—a budding writer absolutely wide-eyed with wonder about what she’s read, and what she might create herself.

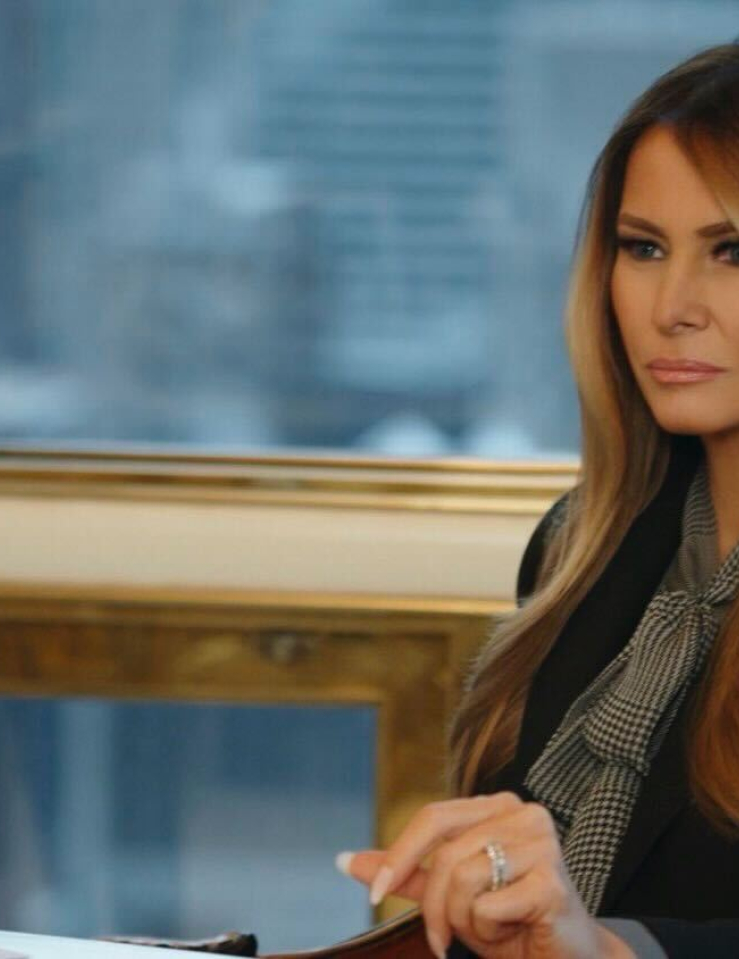

Maybe that all sounds naive, but looking to future generations is what another film, Cover-Up, induces with its portrait of Seymour Hersh and his investigative exposés from My Lai to Abu Ghraib (and beyond, with glimpses of Hersh on the phone with someone about atrocities in Gaza). Directed by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, it’s partly a litany of some of America’s lowest moments as indefatigably revealed by Hersh over a decades-long career, and it’s a reminder of the necessity of, basically, being difficult in the face of wrongdoing. In some ways it’s like a compendium of scandals chronicled in assorted documentaries over the years, chronicled through blood-boiling archival excerpts of politicians and through Hersh’s own insider topspin. Poitras had pursued a film with Hersh for about 20 years—a logical pairing of two trusted secret-keepers—and the crimes chronicled here make one worry about what crimes now are being committed under the current administration, and root for the next generation of journalists pushing for accountability. There’s also time for some humor about Hersh’s son-of-a-gun prickliness, seated behind his desk, as when he mutteringly complains about his papers being on screen while immediately conceding that he had agreed to exactly that.

Landmarks. Courtesy of Camden International Film Festival

Seymour Hersh in Cover-Up. Courtesy of Praxis Films

Remake. Courtesy of Giant Squid

If Cover-Up can feel like a prophecy of downfall through the country’s past sins, part of what Gianfranco Rosi’s Below the Clouds conveys is the passing of empires as naturally as the turn of the earth. It’s ostensibly a series of views on Naples, circling among different perspectives and perches (a bit like Rosi’s Golden Lion winner Sacro GRA [2013]): Japanese archaeologists on a decades-long dig, an afterschool study hall run out of storefront by a greying scholar, a fire department fielding emergency calls from concerned (or bored) citizens, Syrian workers on a Ukraine ship offloading grain, and investigators breaching the secret tunnels of tomb robbers. It’s sometimes easy to omit the obvious about the portrayal of a well-known site, and so it’s worth stating that Rosi’s Naples—shot in a lovely black-and-white that’s appropriately autumnal—is a quiet, depopulated place, where life resides in reflective voices and archival spaces rather than the streets (or food or music).

This approach tends to encourage a long view of things, and to me at least, Below the Clouds bespeaks the fragility of civilization, as we keep seeing the remnants of empires past, with the Vesuvian burial of Pompeii connected to the present through today’s emergency calls about eruption tremors. Passages from Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (1954), projected in a derelict cinema, underline the sense that our appreciation of our counterparts in history always involves a contemplation of mortality. But Below the Clouds is much less heavy or dry than that sentiment might sound, with a warmth and curiosity that lets scenes breathe, like watching two Syrian shipmates chatting in a tiny gym or hearing the study room’s bookish teacher guiding students along in their reading. And in one extraordinary moment, we hear an unexpected domestic violence emergency call that makes all the grand thoughts fall away before drama, eloquently puncturing any grand theorizing in the face of daily lived experience.

It’ll come as no surprise that Lucrecia Martel’s Nuestra Tierra—somewhat plainly titled Landmarks in English—also weaves in themes around empire as it revisits the 2009 killing of Chuschagasta leader Javier Chocobar in Argentina. No one should expect the director of Zama (2017) to deliver a beat-by-beat account of the scandalous 2018 trial, and indeed Martel’s film organically keeps slipping away from the witness testimonies and conflicting reenactments on the hilly site where Dario Luis Amín and accomplices Luis Humberto Gómez and José Valdivieso attempted a mining land grab that led to a confrontation and killing.

Probably recognizing how the apparatus and procedures of the court tend to reinforce established power imbalances, Martel instead lets Chocobar’s relatives take us through their lives and agricultural history with the land. In these segments, we learn the cynical maneuvers through which Chuschagasta land was stolen in the 19th century and—demonstrating the intractability of such landowning dynasties—how that theft was effectively laundered by the time Amin’s family took control. (Even when Martel’s camera stays inside the court, it’s sometimes with a sardonic eye, as when she dwells on an investigating judge’s expectant gaze at a young man delivering water, a snapshot tingling with class tension.) Nuestra Tierra opens somewhat disorientingly with a satellite view of the area and proceeds to return to drone shots of the land, which do not signal vistas from an invisible eye in the usual documentary manner. Instead, the drone in Martel’s hands feels like a witness, with an element of instability: at one point, a bird crashes into the camera. Throughout, there’s the sense that Amin’s enablers might as well be the cousins of Martel’s own Headless Woman (2008).

Martel’s previous feature Zama premiered in Venice too, previewing in the same opening-night slot as Werner Herzog’s Ghost Elephants, about which I have little to say other than: 1) not enough elephants! (and an eternity before South African naturalist Steve Boyes even starts his search for them); and 2) Herzog’s grandiosity shtick, usually harmless enough, tilts into dicey old-man territory in his effusive praise of the San trackers (using them-and-us language). His movie heads to National Geographic soon.

Also opening imminently courtesy of Utopia is Megadoc, Mike Figgis’s bob-and-weave account of the making of Megalopolis (2024). Having directed Nicolas Cage to an Oscar in Leaving Las Vegas (1995, which is how he met Francis Ford Coppola), Figgis brings a filmmaker’s nose for the chaos of (some) filmmaking, making for a better-than-average behind-the-scenes account. It helps to have confidants such as a mischievous Aubrey Plaza or filterless Shia LeBeouf (“I have the least job security of all the actors”), though Adam Driver and Nathalie Emmanuel appear to have been off-limits for meaningful sit-downs. The portrayal might not be surprising to anyone who followed coverage of the film’s expensive and bumpy road to creation, but it’s still remarkable to watch Guardians of the Galaxy production designer Beth Mickle politely explain the point at which there was “no way forward” for her, or Coppola opting to direct remotely from his trailer when he loses patience, or an elegant Milena Canonero wafting through to make selections, or Aubrey and Dustin Hoffman arm-wrestling. It also becomes immediately apparent that the hefty price tag came from keeping the meter running on a large production for weeks on end. Figgis talks to the camera here and there as a casual narrator, but he might speak his loudest when he glosses the multimillion-dollar budgets for each department with numbers on screen. In the end, Coppola says he’d been aiming for a blend of theater and film, which happily is how I’d taken Megalopolis in the first place.

It proved impossible to fit in another movie documentary I was curious about, The (apparently archive-rich) Ozu Diaries, but it wasn’t the only one: Kim Novak received a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, appeared for a lengthy onstage conversation, and was the subject of... Kim Novak’s Vertigo. Alexandre O. Philippe’s latest deep-dive into a classic is rooted in extensive sit-down interviews with a 90-something Novak, which is the film’s main attraction: in-the-moment ruminations on acting choices in scenes or Alfred Hitchcock or a certain Vertigo dress (which Novak digs out, leading Philippe to create a kind of unboxing video within the film). Her candor and sense memories, reaching across the decades after which she shifted from acting to a more independent life painting, outweigh a directorial respect that can make it all feel a bit beholden to its star. For the first half or so, Philippe’s characteristic threading through details of Novak’s life and films can be clever and seductive, but eventually even its 77-minute length tends to tread water. Still, it’s hard to complain about listening to the star of Vertigo, not to mention Bell, Book and Candle (1958), Picnic (1955), and Jeanne Eagels (her own vote for hidden gem, 1957).

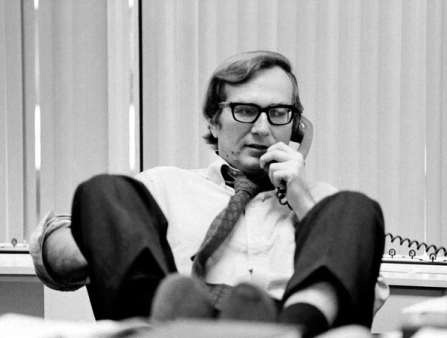

Finally, Ross McElwee returned to Venice, fourteen years after ruminating on his relationship with his son Adrian in Photographic Memory, and quietly delivered a wrenching work in the searching, pained Remake. The innocuous title reflects the film’s early inspiration, an unlikely attempt by a Hollywood producer to remake McElwee’s canonical debut feature, Sherman’s March (1985). But, as with other McElwee films, the director chronicles the shifts and detours that are the stuff of life, most tragically so with Adrian, whose death at 27 after struggles with substance abuse lead the filmmaker to question himself as both father and filmmaker. Adrian seems a budding memoirist in his own right, chronicling his experiences and meditations with candor, yet his father (in his signature murmuring, musing tones) worries that filmmaking somehow encouraged the wrong sort of experimentation. Yet it also feels as if the camera was a legitimate medium of father-son intimacy more than it was a distancing factor.

Mixed in are the predictably risible twists in the Hollywood remake saga, sharp words on the fentanyl crisis, and a visit with McElwee superstar Charleen Swansea (from Sherman’s March and Charleen and more). Charleen’s extensive memory loss, including even her own teaching career, lends another poignant necessity to McElwee’s ongoing project of recollection. Remake shows a beloved documentary artist returning in full form, with a kind of film-letter to a lost son, showing one more way in which the world can end.