Lee Anne Schmitt’s films have a penchant for tracing the history of ideas, usually by exploring the landscapes they leave behind. Her debut feature, California Company Town (2008), moves between the remnants of communities created and controlled by industrialists in the Golden State, while Purge This Land (2017) explores locales from the life of radical abolitionist John Brown. In her latest film, Evidence (2025), Schmitt turns the camera on herself and her own family, following a thread from her father’s work at the petrochemical giant, the Olin Corporation, and uncovering how that company’s wealth helped create a chain of foundations and educational institutions dedicated to nurturing conservative thinkers and disseminating their ideas.

Schmitt traces this propagation as clearly as if following a physical road to get there. She examines how the John M. Olin Foundation’s fellowship program birthed modern conservative grifters, such as Dinesh D’Souza and Ann Coulter, and how its funding supported the first meeting of the Federalist Society—without which, Schmitt argues, “The Right could not have accomplished the slow-motion judicial coup it’s been planning for more than 60 years.”

This broad analysis of conservative ideology continuously links back to its domineering, patriarchal conceptions of the family, which Schmitt posits as “having always been a tool of class control” in America.

Schmitt’s essay films, while historical in subject matter, utilize present-tense images of places as they exist now rather than relying on archival footage. With Evidence, her essayistic practice of handling the history of ideas evolves into filming childhood objects, books from right-wing thinkers, and her own domestic space as she traces a broader conservative cultural coup stemming from the company her father worked for. Schmitt’s film is just an act of journalism exposing these connections, but creates a meditative space in which her personal reflection becomes a way for audiences to process their own place within ideology—making a potential first step in changing it.

Evidence is traveling the festival circuit, premiering earlier this year at Berlinale and subsequently playing at Jeonju and Cinéma du Réel before making its way to the States at Camden. I spoke with Schmitt about her film ahead of its New York premiere at NYFF. This interview has been edited.

DOCUMENTARY: Can you tell me about how long you’ve been working on Evidence, or when you started conceptualizing it?

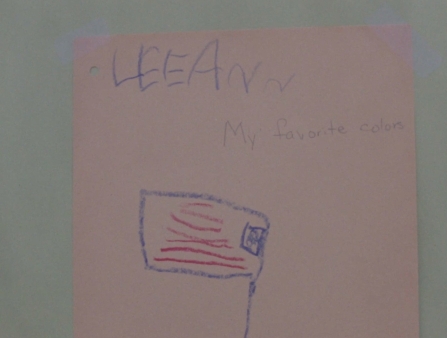

LEE ANNE SCHMITT: It’s always a little hard to find the beginning of my films, because they come out of the inquiry I’m having in daily life. I probably started it back around 2015 or 2016, in some ways because my mom sent me some things from the house I grew up in, like the dolls that are in the film. I was starting to research where we were headed and intellectual developments. I think I did the first filming for the project right before COVID-19 in 2019.

D: When did you find this connection between the Olin Corporation, where your father worked, and all these hardline conservative groups that they were funding?

LAS: I wasn’t aware of the depths of it growing up, but I was aware that there was this association. Maybe not so much with the [John M. Olin] Foundation, but with the milieu around certain ideas. I grew up having arguments with my father about certain belief systems around—well, I guess capitalism, but I didn’t know to frame it that way in eighth grade. I’ve always felt this association between gender, social, and economic constructs.

I first started reading about dark money generally, and then realized that Olin was a good way to enter this larger discussion and connect it to something personal. Olin is really only one of dozens of these donors—it’s this entire movement that I was trying to point to. From 2016 through last year, when the film finished, the public awareness of and the emergence of those social agendas changed. As I did more research, the intonation changed. I did not know the connection to the Federalist Society or to Focus on the Family. My films have all evolved over four or five years, circling around ideas.

D: In a lot of your films, the explorations are built around landscapes. California Company Town involves all these spaces left behind. Evidence is more an exploration of a history of ideas and ideas being spread. How did that change your directing process?

LAS: With the other films, I was interested in looking at a certain history of ideas, like the ideology of a company town. I’ve done it through landscape in part, because I like that process of going into the world and gathering things. The last film, Purge This Land, started to touch on this kind of domestic landscape, and I knew I wanted to go deeper into that, like how does this come into your own day-to-day existence? Being a parent, you spend a lot of time in the domestic space and you become very aware of how that’s being constructed.

The first filming I did [for Evidence] was landscape-based. I went into the manufacturing sites. It really felt necessary to be as vulnerable as possible and be as honest as possible. My investigation around these political thoughts has to do very much with me looking at how people come to believe the things they believe. And then, of course, we spent nine months in the domestic space because of COVID lockdowns. I had these objects from my childhood that I was playing with. The final piece was deciding to use the books to go into this kind of web of thought—a very different kind of landscape.

Evidence is also very similar to my other films in terms of voice, but I think the voiceover is an evolution from Purge This Land.

D: It seems to me like you have two authorial voices: a more factual voiceover and a more personal one when you have text-on-screen, describing memories of your childhood or anxieties about parenting.

LAS: That’s true. The text-on-screen was the first part of the film I did. It’s probably the central gesture of what I was trying to figure out, this experience I had as a parent. I think you sort through the good and bad ideas you grow up with and start to see them manifest and think, “Okay, let me confront this.” The choice of the text-on-screen at first was that I didn’t want to speak it, to be honest. It was one of those choices that stayed and felt correct. There is a little bit of a third authorial voice, too, in terms of essayistic quotations.

I played with layers along the way. Some of it is just rewriting and rewriting, which is a big part of the editing of the films and finding a balance. Some of it is just impulse. The daily barrage of information is overwhelming for most people, so it was important to make space and shift knowledge throughout the film to make it useful instead of yet another accumulation of anxiety.

D: You make information something that you very physically interact with. When you’re first showing the books, you have your hands on them and are pointing the specific quotations with your fingers.

LAS: The material part ended up being a little bit of the logic of the film’s order—exploring the impact on the material world using these objects and the landscapes of the manufacturing sites. We live in these ideas in a way that affects our day-to-day lives and how we embody ourselves. I had a lot of questions when I made this, like: “What is the purpose of this film?” Especially as history has accelerated to where we’re at, a lot of journalists have covered this information. Instead, film is this meditative, collective stasis. Watching a film is an experience and lets you think through things.

D: Your films seem to be about these cumulative effects. When you’re exploring the conservative ideas, you address authority and parenting, and how these conservative thinkers justify hitting their children so that they will respect and love authority, and this has a down-the-line effect on these people’s politics as they become adults.

LAS: It’s a whole system of thought around what the human experience is supposed to be and what the gender experience is supposed to be, and how that’s trained into us as humans. Those connections are really important for us to see in our own lives, too.

Start with your own family structures, start with your own community structures. Make sure you’re bringing the ideals you want there, and then that gives people the strength to think of other political systems. It’s kind of like the small rooms idea—real change comes predominantly from small organizations and communities that feed into larger movements, building up small rooms that operate the way you want them to. That people need both the support and solace, but also the ability to feel seen and called in.

So family, yes, but also classrooms and small screening rooms, readings and other collective spaces. Even nightclubs have a huge impact on social movements. Many of the most impactful artistic moments I have had haven’t been in the larger venues or in the mass market, but in spaces between ten and a hundred people.

Despite the assault on education generally, I have remained incredibly grateful and deeply dedicated to the impacts of the classroom. These ideas around authority and discipline are so deeply embedded in education and childhood in America, they’re really hard to pull out. I hear it from people I teach with all the time, who would never in a million years consider themselves conservative. We have some very strong beliefs of where power sits in the family and where power sits in the classroom and education.

D: I want to ask about your decision to film yourself in this movie. You don’t tend to put yourself physically in your films. In Evidence, you often present you and your son wearing masks, could you tell me a little about that?

LAS: Before I started making films, I had a performance company in my late 20s and I did actually put myself in a lot of that work, as well as some of the early video pieces I made before I moved into essayistic [filmmaking]. It is a realm I am more and more interested in. It is important to be vulnerable, or subjective, in that way, and say, “I am speaking and present.” That is one answer.

The other is that I spent a lot of time with my son over the last 14 years. If you have a smaller child, your house becomes inhabited with all these objects, and you wonder, “How did this object come into my life? How did this action figure come into my life?” A lot of the [objects in Evidence] are the toys that I grew up with. The masks are Halloween costumes I had when I was a kid. I filmed in my backyard and my son would show up, so we’d film together. That footage kind of snuck into the work.

Toward the end, I wanted to do these quite staged moments. It’s a kind of filmmaking I’ve always really loved. It’s a kind of filmmaking that comes out of a certain politic of feminist video work. I think my approach with the last couple of films is to be as simple and direct as possible, and it fits into that ethos: I’m speaking, and this is my messy porch and this is me, and these are the things I have.