Since its foundation in 2001 by Robert DeNiro, his longtime producer Jane Rosenthal, and her real estate investor and then-husband Craig Hatkoff, the Tribeca Festival has been increasingly dismissed by New York’s cinephile set as the home of subpar efforts from actors-turned-directors and fan-service pop culture documentaries.

Since its initial intent was to revitalize downtown Manhattan in the wake of September 11, it makes sense that the festival would platform broadly populist (i.e., profitable) offerings. The festival dropped the word film from its name altogether back in 2021, when pandemic-era anxieties caused an industry-wide lack of confidence in the future of traditional filmmaking. In particular, Tribeca set its sights on amplifying programming across disparate mediums, with concerted emphasis on categories that now include Games, Episodic, Immersive, Audio, and Tribeca X (which, bleakly, aims to “bridge the gap between entertainment and brand marketing”). Of course, AI has also been embraced by the festival. This year, Tribeca presented an entire shorts block of films created with OpenAI’s Sora, which spits out “hyperrealistic” images based solely on text prompts.

While the rebrand signaled the festival’s emphatic catering to commercial trends, the 2025 edition also served satisfying alternatives. Amid star-studded studio fare (including the “live-action” remake of How to Train Your Dragon and Miley Cyrus’s pop opera, the latter of which saw scalpers selling US$800 tickets to confused fans), first-time feature filmmakers and indie stalwarts were particularly prominent in this year’s lineup of 118 titles.

Nonfiction projects were no exception. In the Documentary Competition, the ten world-premiering selections included six helmed by directors making their feature debut. Though only comprising a small fraction of Tribeca’s feature film program, which is still the self-described “core” of the festival, several of these titles also embody the necessity of plumbing below the surface. This is especially true of how one should approach Tribeca’s slate in and of itself; in bypassing the glitzy allure of celebrities and their vanity projects, one can encounter documentaries that survey the rawest depths of this country, clouded by a rather flimsy veneer of extravagance.

The most literal of these examples is Underland, the first feature from filmmaker Rob Petit. Based on the 2019 nonfiction book of the same name by Robert Macfarlane—with whom Petit collaborated on the short doc Upstream back in 2019—the film utilizes a variety of cinematographic devices to tour seldom-seen crevices of Earth. These include LiDAR cameras that create image maps of tight spaces, drones capable of capturing UV light, and a fisheye-lensed camera affixed to the end of an ice bore. Many of these locales are far-flung—including a cave system in the Yucatan previously traveled by ancient Mayans and Canada’s SNOLAB research facility located two kilometers underground—but the most socially sobering spaces are found in the U.S.

While Underland touts cinematic imagery of places previously inaccessible to film crews, it holds at a distance everyday people who may already interact with these sunken spaces in a clandestine rather than scientific manner. A co-production between Sandbox Films, Spring Films, Planet Octopus Studios, and Protozoa Pictures (Darren Aronofsky’s production company), the film’s concerted focus is on the experts and scientists who study the landscape underfoot. This feels especially congruent with Sandbox Films’s output, which features several documentaries that follow scientists as they break new ground in their diverse areas of study. As such, it would make sense for Petit’s film to prioritize the empirical perspective, though at times it feels markedly removed from the very real people who navigate the locations he and his team are probing.

The storm drains of Las Vegas embody the physical realm of the American underclass, which exists directly beneath the opulence and excess that the city is famous for. Guided by an experienced urban spelunker, Petit and cinematographer Ruben Woodin Dechamps traverse these subterranean channels, which are quickly revealed to contain makeshift shelters for a homeless population that has been intentionally relegated to the city fringes. While Underland never features any of these residents on camera, they were widely seen in a May 2025 NBC televised segment about the more than one thousand Clark County residents who reside in these storm drains. “I just try to stay out of sight, out of mind,” one unhoused man told the reporters. Indeed, Las Vegas has been increasingly enacting punitive policies targeting the destitute, including a US$1,000 fine and up to 10 days of jail time for those who are found sleeping in public.

Underland eschews filming the individuals who live there, but fills the ensuing space with a sensorial landscape. The immersive soundscape of this hidden world—echoing steps, audible drafts, the plop of fat water droplets hitting stone—is given priority, as to cater to a sense that is heightened by darkness. The visual finesse of Dechamps’s camerawork is staggering in its own right, not only in terms of the natural splendor on display, but in its portrayal of the experts who usher Petit and his viewers underground. (The only subjects featured are those who, in some professional capacity, are drawn to studying these ecosystems.)

The storm drain segment has an exploratory air to it, meaning that anyone encountered by the film crew would have been caught off-guard and, in turn, might have possibly had their personhood exploited. Yet when the crew stumbles upon a crude assortment of human possessions—clothes, a mattress, food wrappers, and refuse—the team becomes audibly uncomfortable, as if interacting with the owner of these objects would result in imminent danger. In truth, the tangible peril of navigating this space comes from the fact that if it were to suddenly rain on the surface, the tunnels could easily flood in a matter of minutes, a gnawing anxiety that eventually causes Petit, his crew, and their guide to swiftly evacuate at the first sign of dampness.

Another segment that illuminates the evil underbelly of the American project takes place in an abandoned uranium mine somewhere in the U.S. Southwest. The darkness feels even more stagnant here, where the air itself presents a very real, if imperceptible, threat, which is so palpable that neither Petit, his crew, nor their guide physically venture into the bowels of the mine. A drone hums as it flies down the shaft, equipped with a camera that can throw UV light. The walls are immediately cast in a hue of neon green, signaling disastrous levels of radiation. As the drone continues, a dumping ground is revealed, where household appliances and other large, difficult-to-dispose-of items are piled high. While a note is briefly made of how this radioactive waste will leave a lurid legacy for generations to come, there is no tangible reference to the way that Native American communities have, specifically, been poisoned as a result of the uranium mining industry itself and the toxicity that it has spread to their communities.

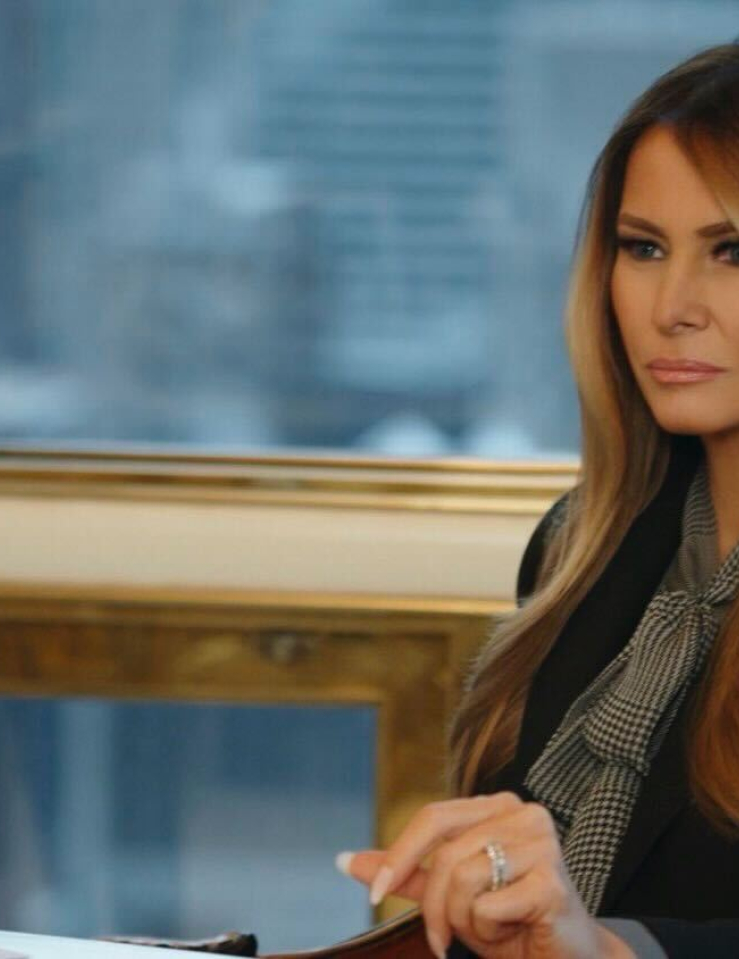

Natchez. Image credit: Noah Collier

Backside.

The historical weight of America’s insidious inequity is more deftly confronted in Natchez, the sophomore feature from Susannah Herbert. Rightly awarded Best Documentary Feature at the festival, the film begins as a candid examination of this titular small town, the economy of which mostly relies on antebellum tourism, as it struggles to remain relevant amid the country’s ongoing racial reckoning. Tour guides don elaborate garments and show visitors around centuries-old mansions, going into granular detail regarding the ornate 19th-century decor that embellishes every room. The vibe momentarily sours when a guide must elaborate on the presence of slaves on these former plantations, even though most typically skirt around the topic.

“They use the word ‘servant’ or ‘help,’ but these were slaves,” says Rev, a local Black activist who has established his own tour company that centers on how Natchez directly benefited from slavery and how Black Americans came to positions of power immediately during Reconstruction. The next scene cuts back to a tour provided by a member of the Pilgrimage Garden Club—an HOA-adjacent organization largely run by white women who sport hoop skirts and ensure all antebellum homes are preserved with utmost accuracy—wherein she refers to one of the former owner’s “favorite servants,” who they so graciously taught to read and write despite the time’s legal restrictions. “He was good to his people,” the guide concludes with a grin, as the all-white tour group nods in affirmation, despite the fact that the phrase “his people” clearly denotes ownership.

Shot by cinematographer Noah Collier (who lensed and co-directed the 2023 Southern-set doc Carpet Cowboys), there is a hazy visual quality to the film—achieved by what appears to be a smear of Vaseline on the lens—which at first feels intrusive, but eventually presents itself as perfectly apt for reflecting the blurriness between Natchez’s unvarnished history and the sanitized, glorified image that its white residents desperately cling to. The instinct to outright ignore the deep-seated racism of the city—at one time the second-largest slave market in the U.S.—isn’t the only tactic used by those who have transformed their familial homes into living exhibits. One such owner, David, prides himself on opening his home to the flourishing LGBTQ+ community in Natchez, often hosting salons for drag queens and similarly well-to-do queer elders.

Amidst the growing right-wing cultural backlash against queerness, David’s efforts at first seem admirable. During the film’s final moments, David, whose voice quivers as a result of his worsening Parkinson’s, channels every ounce of nigh-whispered vitriol he can muster when recounting a private dispute he once had with Hillary Clinton. He reasons that her stance on Black civil liberties caused her to lose the 2016 election. “That’s why she didn’t get elected,” he says, “too much ni***rism.” This frank, unfiltered view on the town’s increased accountability in regard to slavery and Jim Crow is akin to a sinister deathbed confession; it’s shocking that this is what he has decided to articulate for the record.

Herbert isn’t interested solely in capturing this country’s cynical truths. Integral to Natchez is the desire for residents and visitors alike to educate themselves and confront the repercussions of racism head-on. Rev’s tours tend to be frequented by white people, all of whom are shown to truly meditate on the blunt facts, figures, and anecdotes that he offers. Tracy, a guide at one of the more conventional antebellum plantations, becomes gradually more interested in understanding the roots of Natchez, eventually embarking on one of Rev’s tours herself. A local woman named Debbie becomes the first Black member of the Pilgrimage Garden Club after she purchases a former slave dwelling and begins to give tours focused on their lives. Tension may continue to fester within this broader political moment, but Herbert’s film is an exhilarating distillation of how clinging to traditionalist American values often belies an inherent bigotry.

More observational in style, but still an overt condemnation of pomp and circumstance taking precedence over human lives is Backside, from director-cinematographer Raúl O. Paz-Pastrana. In this case, the funky regalia and mint juleps associated with the Kentucky Derby are strewn aside in favor of the predominantly Latino grooms tasked with mucking stables, feeding, watering, grooming, and caring for the racehorses. While jockeys and trainers serve as the mostly white public faces of horseracing, the immense toil of workers—who probably spend more quality time with the animals than the jockeys, trainers, and owners combined—are given little conventional notice.

Although Paz-Pastrana filmed between 2021 and 2023, the staunch anti-immigration stance of Trump’s second term casts an anxious pall while viewing the film. It’s long been evident that the U.S. economically relies on cheap migrant labor, but requisite respect (including providing basic human rights) for these workers has not been normalized on a societal scale. In lieu of offering a political and cultural brief on the current climate for grooms, particularly those who are migrants, Paz-Pastrana employs verité footage to acutely enmesh viewers in the intraspecies empathy formed from the daily drudgery of tending to these horses. Prizes, fame, and glory may be reserved for those with recognizable positions within the sport, but the body language expressed by horse and groom conjures genuine care, trust, and love.

In the vein of Frederick Wiseman, Paz-Pastrana also documents the Churchill Downs racetrack as an institution, allowing the minutiae of every function to speak for itself: staff announcements made exclusively in Spanish, an employee-organized procession for the Virgin of Guadalupe. Certain employees are also given the opportunity to address the camera, relaying their own experiences, which include near brushes with powerful hooves, struggles to unionize, and, in the most bittersweet scene in the film, one elderly gaucho’s insistence on feeding candy to his horse. His wistful smile gives way to a crestfallen expression when a companion reprimands him for spoiling the creature, noting that the groom at the next stable may not offer the same kindness, causing the horse to then crave what it cannot have. Another harsh reality of the job is that grooms often adopt a nomadic lifestyle, moving to different stables—and caring for new horses—across the country in preparation for the next racing seasons.

Though Backside does eventually document the Kentucky Derby, it does so with deflated interest. For a few short minutes, posh attendees are contrasted with the grooms who host an informal congregation for family and friends on the backside of the track. As the horses rest after the race before being carted to their next destination, the grooms exchange brief farewells. The final shot, which sees the stables completely unoccupied, meditates on the future of many industries if immigrants are cast out—without grooms, there is no horse racing. The filmmaker’s delicate yet intentional gaze allows for this stark truth to resonate without preachiness.

Underland, Natchez, and Backside register as refreshing departures within Tribeca’s documentary programming because the topics dissected are elevated by filmmakers flexing aesthetic and narrative finesse. Not content with simply pontificating an agenda, they embrace the potential for playing with the medium on an artistic level. As a ceaseless stream of commentary regarding this country’s staggering cruelty toward marginalized populations dominates airwaves, headlines, and social feeds, the idea of being fully immersed in these niches offers more insight than any barrage of statistics or talking head interviews ever could. The opportunity to enmesh ourselves in the quotidian realities of strangers remains radical.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Fall 2025 issue.