Last October, Louis Sale and Bernard Raheem Ballard accepted awards for their films at the first San Quentin Film Festival. Like many emerging filmmakers, Sale and Ballard accepted their film festival awards with eyes wide open to the possibility of what these achievements signaled for the trajectory of their lives. The two were from the famous Media Center of San Quentin, California’s oldest prison. After the festival, Sale was approached by a buyer who wanted to turn his film into a blockbuster movie. Ballard was awarded a US$10,000 grant for future film projects and learned that his film was under consideration to be shown on PBS.

A week later, that possibility evaporated.

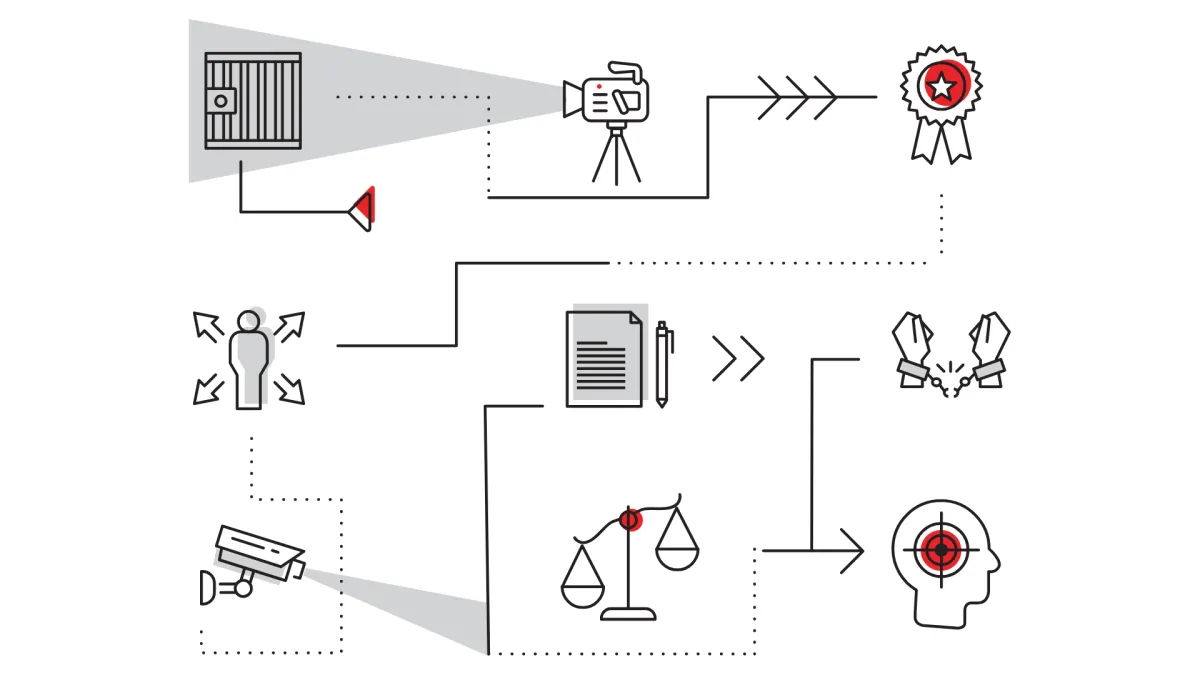

The purpose of bringing a film festival inside San Quentin Rehabilitation Center was to give the industry insiders an opportunity to see the creativity and value of the work incarcerated people could create. The film festival also gave incarcerated filmmakers the opportunity to compete with people in the outside world to prove their value and get an opportunity to receive fair and equal pay and treatment from the film industry. With Governor Gavin Newsom’s promise of a California model, and California voters about to vote on a proposition concerning involuntary servitude, the political stakes were high.

San Quentin Film Festival was created by Cori Thomas, a longtime prison volunteer, and Rahsaan “New York” Thomas (unrelated), a formerly incarcerated person, two people who understood the importance of the political moment. R. Thomas had a lot of experience producing award-winning media while inside San Quentin. During the festival, he shared from the stage that

while incarcerated, I was a Pulitzer prize finalist with Ear Hustle podcast…[and] published 42 stories in 31 months in major publications through creating the Empowerment Avenue program. I co-starred in the documentary film 26.2 to Life: Inside the San Quentin Marathon, a film about the transformative power of the SQ 1000 Mile Running Club. I also produced my own documentary called Friendly Signs, which focuses on an incarcerated man who learns sign language to communicate with his brother.

According to Thomas, as a result of his media production work, after he was released from prison he had plenty of cash in the bank, which made for a much smoother transition compared to others who left prison with only the US$200 worth of gate money provided by the prison. Thomas affirmed that he co-created the San Quentin Film Festival in hopes of inspiring Hollywood elites to see the humanity and skill of the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated. He also challenged those present at the festival to help campaign for fair and equal opportunities for employment and pay, not only for those reentering society but also for those still in prison.

Last October’s first edition (a second edition was completed in October 2025) was a two-day premiere event. Guests included comedians W. Kamau Bell and Jerry Seinfeld, actor Kerry Washington, and Cord Jefferson, who won the Academy Award for best-adapted screenplay for American Fiction (2023). The infamous prison’s garden chapel was transformed into a darkened theater with a huge movie projection screen, where invited guests sat among a packed crowd of reporters, Hollywood insiders, prison volunteers, officers, and incarcerated people.

The crowd viewed critically acclaimed films about prisons, such as Sing Sing (2023), Greg Kwedar’s Oscar-nominated adaptation of the true story of a theater troupe inside a prison; The Strike (2024, which was an IDA Enterprise grantee), JoeBill Muñoz and Lucas Guilkey’s film about a coordinated prisoner hunger strike that shut down one of the largest supermax facilities in the country; and Daughters (2024), Angela Patton and Natalie Rae’s documentary about four little girls preparing for a dance with their fathers, who are incarcerated in a D.C. jail. An audience Q&A session with directors, producers, and even some actors followed each film.

[San Quentin Film Festival] also gave incarcerated filmmakers the opportunity to compete with people in the outside world to prove their value and get an opportunity to receive fair and equal pay and treatment from the film industry.

The San Quentin Film Festival set itself apart from other prison education initiatives by including a competition section for films made by incarcerated individuals. Many incarcerated filmmakers walked away as winners. Sale and Ballard stood out.

Sale won the Best Short Documentary Film Award from IDA (which publishes Documentary) for his film, Healing Through Hula, featuring shirtless men with glazed muscles in red pa’u skirts who chant, dance, and celebrate their culture while residing inside the barbed-wired Bastille by the Bay. Ballard won both the IDA Supported Artist Award and the American Documentary OSF Short Film Award for his film Dying Alone, which follows three elderly men who are seriously ill and have filed petitions for compassionate releases.

The undercurrent of Dying Alone is the rising health care costs of an aging prison population and questions about how public safety is served by keeping people locked up who are disabled and near death. The main protagonist is a frail Hispanic man lying in his prison cell with oxygen tubes in his nose. He has been given a diagnosis of less than a year to live. Another man needs a walker to get around, while still another needs a cane and wears a high yellow vest to alert staff that he cannot hear well and is mobility impaired. “The prospect of dying alone in prison inspired me to make this film,” said Ballard when accepting the award. He was 22 years into a 38-to-life sentence when he completed this film.

However, as soon as the movie lights turned back on, Sale and Ballard were confronted with a harsh reality. From American Documentary (AmDoc), Asad Muhammad reached out to Ballard with the benefits of his award, which included digital distribution of Dying Alone via AmDoc’s website and Youtube channel, consultations for an impact campaign, and consideration for PBS distribution. But Ballard couldn’t accept. He explains, “I told our sponsor, Pollen Initiative, that I had an opportunity to get my film shown on a larger scale. They told me that I had to wait until I get out of prison.”

Sale was told a similar thing. In fact, someone allegedly tried to purchase his film before the film festival. But Sale declined to comment any further on the issue.

I told our sponsor, Pollen Initiative, that I had an opportunity to get my film shown on a larger scale. They told me that I had to wait until I get out of prison.

Bernard Raheem Ballard

The Contract Controversy

Pollen Initiative, formerly known as Friends of San Quentin News, is the nonprofit organization that pays for some of the cameras and equipment the media workers use to make their films. According to several sources connected to the media center, who wish to remain anonymous, Pollen doesn’t want media tools they purchase used for any personal ventures that don’t benefit the organization itself. Ballard says he informed AmDoc’s Asad Muhammad that due to institutional restrictions, he couldn’t fulfill any contract at the time.

What happened next concerned Ballard. An employee from Pollen Initiative allegedly came into the Media Center and told him to sign a contract. “They told me that the contract is just to prevent any future problems similar to what happened with my film and Healing Through Hula,” he said. “The contract required me to relinquish ownership rights and any right to compensation for my film in perpetuity.”

A copy of the contract from Pollen Initiative confirms Ballard’s concerns. The contract reads in part:

“I understand and accept that any work created at San Quentin using the facilities, computers, cameras, and recording gear (and any other equipment that does not belong to me) is the property of the State of California. Furthermore, I understand that I am not entitled to any monies generated by these projects, now and in perpetuity.”

Ballard refused to sign.

“I own the film,” Ballard says. “I am not signing any contract forfeiting my rights to the film.” Ballard also alleges that the Pollen employee then told him that those who refuse to sign the contract couldn’t present anything to the next film festival, nor could they be a mentor for the cohort presenting material to the film festival.

Pollen Initiative created the contract after the film festival. It was supposed to be signed by everyone in the Media Center who planned to participate in any future filmmaking projects or film festivals.

According to Ballard, most Media Center workers refused to sign the contract. “I feel like they wanted us to sign our rights over so they can make money, while we get nothing in return,” he says. “No reentry fund, nothing to help me pay my restitution to my crime victims. Nothing. I could see a mutually accommodating agreement, but not a complete confiscation of my film.”

Incredibly, Ballard was found suitable for parole on the same day he won his awards. He was within five months of his release date. “I’m making plans to pursue a relationship with POV/America Reframed [the PBS strands programmed by AmDoc] upon my release,” he said.

When Documentary reached Muhammad for comment, he affirmed, “I plan to extend this timeline through 2026 to complete some of these offerings with Raheem.” Before the 2025 edition of the San Quentin Film Festival, AmDoc also extended its sponsorship, without OSF.

But before Ballard was released, Dying Alone was uploaded to YouTube, which appears to curtail any plans for a distribution deal due to its availability.

The only organization with the ability to upload Dying Alone to YouTube is Pollen Initiative. Several anonymous sources say that Pollen’s executive director, Jesse Vasquez, uploaded the film. Pollen Initiative has declined to comment on what happened to Sale and Ballard and their films, and directed Documentary to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), the state agency responsible for the operations of the prisons and parole system.

A CDCR spokesperson promised to respond, but as of printing Documentary is still awaiting a response.

Ballard was released from prison in March 2025.

San Quentin prison officials did not ask Ballard to create Dying Alone as part of his criminal punishment. But they did give him permission to create media content. Ballard took advantage of a unique opportunity and spent months being chaperoned around the prison with bags of camera equipment and a small crew of assistant media workers. He interviewed incarcerated individuals, prison staff, and medical doctors. He developed his story arc. He wrote his script. He found his protagonists. He sat at a computer practically seven days a week doing postproduction, editing, coloring, finding the right image and tone, mixing and mastering and engineering his artistic material to present to the film festival.

Bottling up the individual creativity of Black and brown and other underserved people in prison communities for the empowerments of some corporate entity should be concerning.

What led to the success of the San Quentin Media Center is the liberty that was once inaccessible to people who live in the prison. Pollen Initiative’s origins are tied to the San Quentin News, which was resurrected in 2008 after a 25-year shutdown by Michael Harris, the founder of the Death Row record company, while he was incarcerated at the prison. Before then-Warden Robert Ayers retired, he spoke to Harris about helping restart the publication created in 1940. After Harris was released from prison, other incarcerated men stepped up to independently run the publication. The prison refused to financially support it. New leadership sought grants and donations. Eventually, a nonprofit organization was formed called the Friends of San Quentin News, which was rebranded as Pollen Initiative.

Other media productions inside San Quentin are also independently funded. In 2017, the Ear Hustle podcast was created by Earlonne Woods, who was serving a life sentence, and Nigel Poor, a prison volunteer. It quickly became an overnight success, winning awards and reaching 80 million listeners globally. In 2019, KALW Public Media’s Uncuffed podcast moved in next door. It was co-created by KALW and incarcerated individuals Greg Eskridge and Thanh Tran, and others who were serving life sentences and have since been released. Uncuffed recently won its highest honor from the Society of Professional Journalists. The only thing the State of California provides these media platforms is the space to operate. They do not support these platforms with state funds. Each platform raises its own grants and donations.

But CDCR and San Quentin do take credit for the success of these platforms. Countless tourists visit the Media Center on a weekly basis. High school kids, social justice groups, public defenders, prosecutors, politicians, and celebrities visit the iconic location. Many leave astonished to learn that those who work in the Media Center never return to prison once they are released. Governor Newsom, comedian Jon Stewart, ex-NFL football player Marshawn Lynch, Jelly Roll, Duck Dynasty cast members, and even Haakon, the Crown Prince of Norway, have been spotted there mingling with the media makers, praising their intellectual work.

In fact, Newsom nodded to San Quentin News and Ear Hustle as partial inspirations for both a state-of-the-art rehabilitation center he wants built in the prison and his move to rename San Quentin State Prison the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center. He made this announcement inside the prison in March 2023.

The ongoing US$239 million Nordic-designed education facility is set to open in January 2026. The plan is to scale up the innovative programs from the media center and other locations. Filmmaking is set to be one of the premier programs at the facility.

Having a film festival and scaling up filmmaking in a prison is forward-thinking. But at what cost? Ballard didn’t get to capitalize on his film. Sale didn’t get to capitalize on his film. Moreover, when the accolades came pouring in, the Media Center sponsors noticed that Ballard had made a film. When money became an issue, ownership became one. With the expansion of the media facilities, countless other incarcerated filmmakers will face this same predicament. Even worse, any future award may not go to the incarcerated individuals at all.

Bottling up the individual creativity of Black and brown bodies and other underserved people in prison communities for the empowerment of some corporate entity should be concerning. What will happen when the grassroots juke joint in the back of the prison’s education annex, known as the media center, scales up as part of the corporate machine? Will the mass production of rehabilitation films lead to more exploitation?

Precedent and Payments

This is not the first time San Quentin has tried to creatively annihilate and rebuild individuals as automatons who only help maintain the system. Understanding what happened to Sale and Ballard requires examining intellectual property rights, labor exploitation, and the line between rehabilitation and profit extraction within the American prison system.

In his book Ghost in the Criminal Justice Machine: Reform, White Supremacy, and an Abolitionist Future, Emile Suotonye DeWeaver, formerly incarcerated at San Quentin, explains how exploitation happens in these creative spaces: “I’ve struggled to feel seen, and it left a hole that needed to be filled by other people’s love and validation. The nonprofit organizations that run many prison programs exploit this hole. I don’t think they do this intentionally; blinded by the imagination problem, they think they’re empowering incarcerated people.”

DeWeaver is specifically referring to Marin Shakespeare Company, a nonprofit organization operating in San Quentin, that fuses drama and therapy to inspire public sympathy toward people in prison. DeWeaver performed in plays, wrote scripts, and played musical instruments for the program while incarcerated. He enjoyed the benefits of the attention. “The program allowed me to experience the connection I needed, and the impact of my performances and endorsements of Marin Shakespeare helped it generate donations. I happily made this trade-off, enjoying the benefits of being seen and celebrated, but that doesn't mean I wasn’t being exploited,” he says.

California law distinguishes between slave labor that is meant for criminal punishment and to maintain the system (working in the kitchen, hospital, yard crew, building porters, clerks etc.,) and intellectual labor of an incarcerated person’s mind, which is a product of free expression (writing a screenplay, manuscripts, journalism) that is not being done to punish the offender. Thus, California law protects an incarcerated individual’s right to own and sell or convey personal or real property and artistic material, including written manuscripts and handicraft items made by the incarcerated individual (California Penal Code, Section 2601).

Almost 70 years ago, a San Quentin warden tried to prevent prisoner Caryl Chessman from selling his book The Face of Justice. In 1959, a Marin Superior Court judge ruled that the warden couldn’t do it. The court stated: “An odor of totalitarianism infects the concept that any product of the prisoner’s mind automatically becomes the property of the state. While a free society recognizes the need for incarceration of offenders, it can claim no possession of the prisoner’s mind.”

Pollen Initiative’s approach isn’t the only possibility. There are current models of creative ownership within San Quentin that treat incarcerated makers as full collaborators. For KALW’s Uncuffed, incarcerated podcast students also sign a contract. Unlike Pollen’s demand for an ownership handover, the Uncuffed production contract is a licensing agreement created by formerly incarcerated individuals and UC Berkeley students that explicitly states that it is “designed to protect incarcerated people.” The contract language reads: “You (the incarcerated individual) own your story. You also own any recording you yourself make as part of this program. You can use those recordings later, anywhere, anytime, forever.” Similarly, Mount Tamalpais College, an independent junior college operating inside San Quentin prison, uses a licensing agreement to publish written articles, essays, poetry, and art on their OpenLine Blog and OpenLine Anthology platform.

An odor of totalitarianism infects the concept that any product of the prisoner’s mind automatically becomes the property of the state. While a free society recognizes the need for incarceration of offenders, it can claim no possession of the prisoner’s mind.

“Nobody can just take your intellectual property and represent it as their own,” says Lamavis Comundoiwilla. He is an incarcerated individual who devotes most of his time to the William James Association (WJA), an arts and corrections program at San Quentin. WJA is a nonprofit organization dedicated to fostering positive changes through the arts. Comundoiwilla uses their workshop to fuse pointillism and other painting styles to create portraits of African queens. He displays his finished products at art expos and transports them back and forth to different events inside the prison. He said he has donated many paintings to WJA and others. He also sells some of his art for a profit.

According to Comundoiwilla, incarcerated people’s creations, like all others, are protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This protection comes from article 27 of that document, which mentions intellectual property rights as human rights. It states: “Everyone has the right to the protection of their moral and material interests resulting from any literary or artistic production, of which they are the author.”

There are legal protections in the United States. Title 17 of the U.S. Code of Copyrights also protects original works of authorship from unauthorized use, granting exclusive ownership rights to the person who creates the product or idea. However, these laws do not necessarily prevent infringement. Comundoiwilla says he was driven to address how common intellectual property disputes are:

When I started hearing about the content created by my incarcerated peers being taken and used by others, I had this vision about creating a platform to help protect artists of all forms—painters, poets, musicians, journalists, and even filmmakers. I eventually reached out to some people who helped start Artworks Initiative, a nonprofit organization that is designed to protect our work and act as a private registry. It acts as a poor man’s copyright to protect content from unauthorized use.

Artworks Initiative (AI) created a private registry and platform for a community of talented artists who are unable to protect and promote their own content. The artists are incarcerated, formerly incarcerated, or at-risk youth. AI claims to promote the work to benefit the artists and protect them by surveilling the internet for unauthorized users and then sending cease-and-desist letters.

The other contested question of the Pollen Initiative contract concerns compensation. Another section reads: “I understand that I will not be compensated for my work on any projects as part of the film program beyond that already agreed upon pay that comes with my work at San Quentin.” Media Center workers earn about 45 cents an hour out of the prison’s allotted budget to perform certain duties.

There are some barriers to compensation. Neither Pollen Initiative nor any other organization that is approved to operate in the prison can give incarcerated individuals any gifts, tips, compensation, or other payment without violating rules against overfamiliarity (California Code of Regulations, Title 15, Sections 3401 and 3425). Approved prison volunteers are treated just like prison employees when it comes to these rules. For example, earlier this year, student researchers for a sociolinguistic labor study assignment concerning code-switching in a carceral educational setting performed more than 70 hours of intense intellectual labor. When a volunteer professor requested permission to pay the students for their labor, MTC, the prison’s contracted operator, denied the request. They couldn’t compensate the students without violating prison rules against overfamiliarity.

But this doesn’t mean incarcerated individuals cannot be paid in other ways—there are many historical examples of organizations paying incarcerated individuals for their creative work. The PEN America Prison Justice Writing Program has supported the creative works of incarcerated individuals for more than 40 years by providing cash prizes of $150–$300 to incarcerated people for poetry, fiction, plays, screenplays, and memoirs. The Prison Journalism Project, which started around the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, now pays about $50 for articles, op-eds, and essays. In fact, many publications pay incarcerated individuals for written essays and articles, including Solitary Watch, The Appeal, and Prism Reports, which created a Right 2 Write (R2W) platform specifically for incarcerated writers. The Appeal pays a dollar a word. Prism pays 50 cents a word.

Incarcerated individuals also can profit from book sales. Decades after Chessman’s case, books by incarcerated writers are numerous, from The Redeemable by Sammie Nichols, a book of poetry; Last Time I Checked I Was Alive, written by Demiantra Maurice Clay, who was recently paroled; and Finding Freedom and That Bird Has My Wings, which became part of Oprah’s Book Club, written by Jarvis Jay Masters.

Incarcerated individuals also have the right to use a power of attorney to manage bank accounts, estates, and other property and assets.

Filmmaking is not just about holding a camera, editing, coloring, and checking for sound. There has to be a story to tell, and doing that includes storyboarding, mapping, and writing arcs and plots. Thus, the script writer is no different than a book’s author. They both own their work.

The mixing of images and sound is also an art form. Audio must be engineered to match the close-up shot of a face or the scream heard in the distance. Only a true native Pacific Islander can tell the story of Healing Through Hula and make people feel the cultural connection.

When Dying Alone was nearing its conclusion, everyone in the audience thought the main protagonist would die in prison. But the sadness suddenly turned to joy when a van pulled outside the gates of San Quentin and dropped him off to his family. Yes, he died. But he did not die in prison, and he did not die alone. The audience was happy and relieved. The creativity that generated those emotions belongs to Ballard.

Preparing people to go home from prison and be somebody’s neighbor takes more than a skill set. It takes opportunity. Ballard had a right to be released in five months with his film in hand to take advantage of a distribution opportunity. Otherwise, what’s the point of it all?

Editor’s Note, November 13, 2025: This piece has been updated to reflect OSF non-involvement in the AmDoc award for 2025.

Editor’s Note, January 2, 2026: The subheading was amended to clarify the nonprofit organization that the piece examines is the Pollen Initiative, not the San Quentin Film Festival.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Fall 2025 issue.