Rebecca Miller has mainly worked in fiction, writing novels or directing films like Angela (1995) and The Ballad of Jack and Rose (2005). But she’s no stranger to biography, having directed a film about her father, the famed playwright, with Arthur Miller: Writer (2017). Her latest documentary is about a figure who’s easily of Arthur Miller’s stature, though in a different medium—Martin Scorsese, whose oeuvre includes nonfiction works like The Last Waltz (1978), Italianamerican (1974), My Voyage to Italy (1999), and Public Speaking (2010). In Mr. Scorsese, Miller sits down with the director to discuss his life over the course of five expansive episodes, starting with his youth in New York City and continuing through to the production of Killers of the Flower Moon (2023).

Through interviews with the filmmaker and his many friends and collaborators, along with copious clips from both his films and his influences (often cross-referenced with extensive splitscreens), Mr. Scorsese posits an expansive exegesis on Scorsese’s work, exploring how his films express his personal journey through shifting ideas around faith, violence, guilt, masculinity, community, and America.

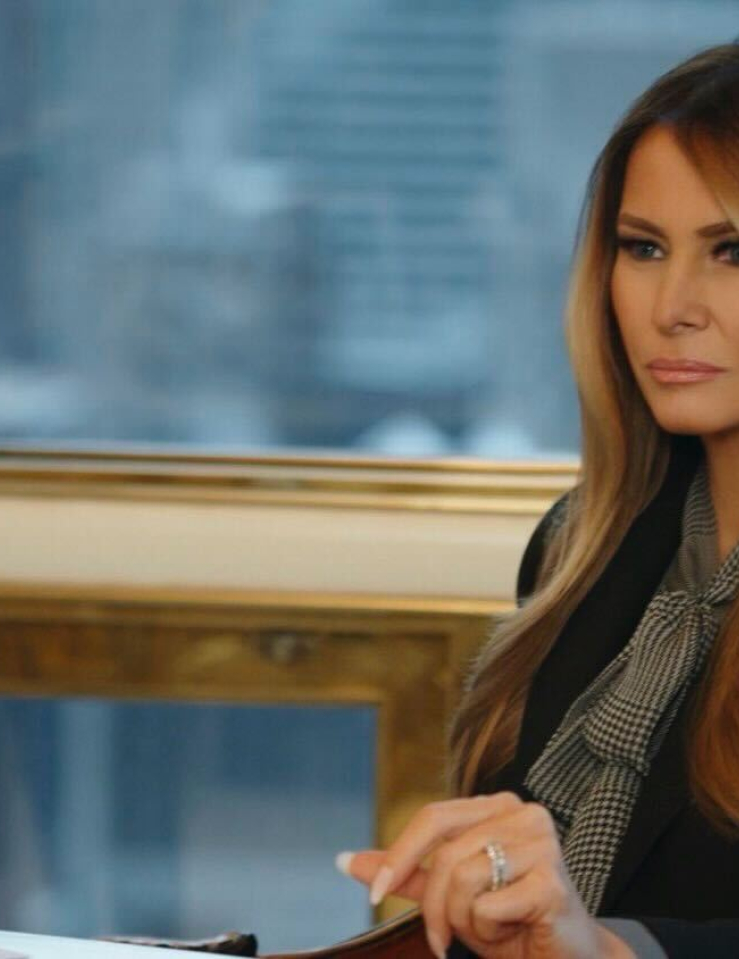

Ahead of the series’ premiere at this year’s New York Film Festival, with its release on Apple TV+ set to follow not long after, Documentary sat down with Miller over Zoom. We discussed how Mr. Scorsese came together, connecting with elderly former gangsters, and how Scorsese’s style rubbed off on her. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: How did you get Scorsese and Apple on board with this, and how long has this project been in the works?

REBECCA MILLER: Apple came on board a bit later in the process. It really generated from a conversation with Damon Cardasis, my producing partner at Round Films. He asked who my ideal subject would be, and Martin Scorsese immediately came up. We thought, well, why not just ask and see? It happened that we knew his producing partner for documentaries, Margaret Bodde. She said there were people circling, but he hadn’t said yes to anyone.

She talked to Marty and told me to write him a letter, which I did, and that led to a little meeting with him. By the end of the meeting, it was clear he was ready to do this. This was a couple of days before the pandemic really hit and everybody disappeared. He came upstate to my house and we worked on my porch, which is why some of the interviews are outside, in that bucolic setting. That first shoot was financed by me and the producers. Apple came on after that.

D: Scorsese has ample experience as a director of documentaries. How was he as a subject? Was he used to it, since he’s been talking with the press for decades, or was it an adjustment for him to be on the other side of the camera in this way?

RM: I never tried to manipulate the conversations, and I didn’t coax him. I approached it through what I would call a sort of radical listening, meaning I was really listening and really responding. And somewhere along the way, he chose to be very present and honest with me. He is perhaps more honest about himself than any person I’ve ever met. Perhaps it’s because of how our relationship developed, but it was very much me following breadcrumbs into the forest.

D: How did the portrait’s form as a five-part series come to be? Were there more at some point? Did it take any negotiation with Apple to get the number of episodes you needed?

RM: Originally, I thought of it as a single film, but after about a year, I realized there was no way I could do it in one piece. I thought maybe it was two pieces, then it kept growing, and now it’s five. By then, Apple had already moved it from their features department to the multi-part department. There wasn’t any need for negotiation. They were really amazing partners in that respect. I sent them a rough version, and they agreed that it was the format we needed.

There wasn’t a cut that was much longer. The focus is his life and art—the man creates the art, then the art creates the man. Five episodes were what I needed for the story I was telling. Now, if I were making lists or going over his complete filmography, that would have taken longer. We deal with 32 of his films, which is a lot. But if I were doing something complete, I would include all his documentaries and television. Hugo is not included because it’s an immense work, and it didn’t fit into the part of the series that was about that moment in his life. The films I chose to emphasize are the ones that ended up in the portrait.

D: Does that mean you went into it with an idea of how much you would emphasize certain films?

RM: My editor, David Bartner, and I were very open. There was a time when we had a voiceover. We tried many different ways of structuring the series. There were a lot of experiments. This was not a piece where everything was laid out ahead of time. There were certain films where there was more going on with him personally, where the dance between the film and his life was more apparent. Those were the films that tended to be explored a little more. I have a responsibility to him as a great artist to talk about his work and give a sense of its breadth and depth, but I also have a responsibility to the viewer to entertain them and keep them invested.

Courtesy of Apple TV+

D: You end up at a story structure that’s mostly linear, though with some jumping back and forth to emphasize certain emotional connections or themes.

RM: We arrived at a more linear structure in part because it was important to emphasize the causal chain of Scorsese’s life. We need to see how his changing self creates different work, and how the work reflects those changes. That made linearity a necessity, that biographical thrust.

D: What ideas did you have that ended up getting discarded?

RM: Oh my god, we tried so many different ways of doing things. I wish my editor were here to remind me of some of the versions. We tried one cut partially told from the point of view of the dog he had in the ’80s—Zoe, I think her name was. You have to be free when cutting a documentary, and do all sorts of things that don’t work so that you can find the things that work. In the end, voiceover wasn’t necessary, and we realized that early on. It’s more complicated to cut [voiceover], because you don’t have a free ride. You can’t give any information that isn’t found within the archive or the interviews. You have to sculpt it very carefully.

D: You have some great access to people from Scorsese’s personal circle here. You even talk to the real guy who inspired Johnny Boy in Mean Streets [Salvatore “Sally Gaga” Uricola], which is an incredible get.

RM: I wanted to connect in an almost somatic way his childhood, the neighborhood, with some of these archetypal figures he knew who end up in his films in different forms. At the start, I never dreamed that we wouldn’t get to Mean Streets until the second episode. When we were cutting the first chapter, which is about his childhood and his early films and NYU, there was a version of this that’s 15 minutes long. But that just wasn’t enough. I felt you needed to understand the emotional geometry of that family, their neighborhood, the way the churches were across the street from the mob social clubs. These are all important in understanding him as a person.

Robert Uricola is still friends with Marty, and so is John Bivona, so it was easy to set those interviews up. I wanted viewers to have a real sense of what it was like to be Marty in those early days, what his life was like. The sound of their voices was so important to me. As for Robert’s brother [Sally Gaga], it happened just as you see it in the film—Robert called him up in front of me. I thought we would never find him, but then he did turn up and we weren’t prepared at all. But that actually made it much better, I think, because he didn’t have time to prepare and neither did I. It was like a real encounter.

D: You make a lot of use of splitscreens in this, whether it’s positioning Scorsese or someone else talking about his films with clips from those films, or comparing different works with each other. It’s very effective at viscerally conveying to a viewer what they’re talking about.

RM: You used the word “visceral,” and that’s exactly what I wanted. These are much older people talking about things that happened a long time ago. You want to feel how they did when they were young, or understand what they’re talking about if it’s archival material or one of his films. It was important to me that this be an engaging cinematic experience. So I’d use a splitscreen because I wanted to see the person talking as they were at the time they’re recounting, or if they’re comparing different films, I wanted you to feel the comparison. Part of it was inspired by Marty’s own use of splitscreens, as well as the folks who made Woodstock—it’s so beautiful in that film.

People are so visually sophisticated now that I feel we can drink in a lot of information at once. You can hear somebody talk about something while watching two things at once, and all of that can go into your brain at the same time. This is a long piece, and you have to keep it moving.

D: It’s funny that you mention how used we are to looking at multiple screens. We know that Netflix executives push for their films and TV to be “second screen content,” to be consumed passively. This is like the obverse of that, asking for active engagement instead.

RM: Exactly. You decide how your eye moves across the screen. I give you all the information and you get to listen to it. You can watch it again if you want, but you have to pay attention.

D: You mentioned that the splitscreen was partially inspired by Woodstock (1970, directed by Michael Wadleigh and edited by Scorsese, Thelma Schoonmaker, Wadleigh, and four others). You have your own sensibility as a filmmaker, but are there other ways that the Scorsese style may have influenced you, whether small or big?

RM: I do think that some of his style rubbed off on me, in a sense of the way he uses music and some of the cutting. I think this is probably also the most masculine film I’ve ever made. Even though Marty did not see this film until it was done, and he had no involvement in the editing, it still felt like we were making it together. It was as if the film absorbed his way of thinking. There’s no explaining something like that. It’s just that if you listen hard enough, you hear what you need to do.

D: It makes sense for the analysis to resemble its subject. Which, as you said, helps the audience understand the subject better.

RM: You can’t make a movie about Scorsese that isn’t at least trying to be as entertaining as a Scorsese movie! You have to try.