At its Berlinale premiere in February 2025, director Juanjo Pereira introduced Under the Flags, the Sun with a simple statement: “I thought I was making a movie about the past, but actually I was making a movie about the present.” Given that Pereira’s debut feature focuses on life in Paraguay under President Alfredo Stroessner, a brutal dictator who presided over one of the world’s longest authoritarian regimes, that statement had an undeniably ominous resonance.

A chillingly topical film constructed entirely from archival footage, Under the Flags, the Sun harnesses newsreels, documentary travelogues, and propaganda footage to reconstruct Stroessner’s reign, from his rise to office on a wave of nationalist fervor in the 1950s, to the consolidation of his power through corruption and violence, to his 1989 overthrow in a military coup. The documentary serves as a compelling introduction to a historical chapter that has been underexplored in cinema, but it’s more than a work of historiography. Paraguay has no official national archive, and much of the audiovisual material produced in the country during Stroessner’s regime has been lost or damaged. Pereira spent several years researching for the film, seeking out surviving footage in Paraguay (where tapes and reels were sometimes fished out of the garbage) and filling the gaps in this partial, rapidly disintegrating audiovisual record with rare images, reels, and documents sourced from other archives around the world, from exoticizing travelogues to sober news reports.

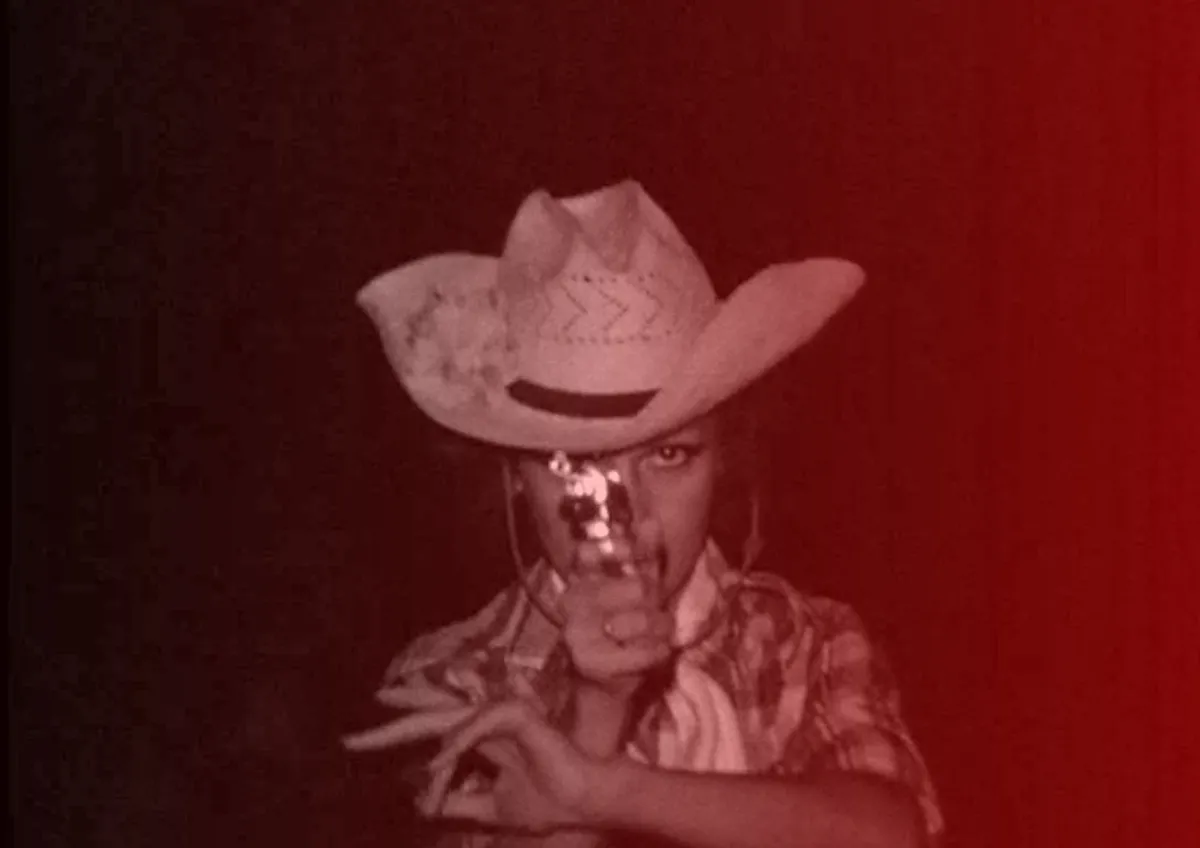

Combined with playful editing techniques, atmospheric sound and pointed use of color (Stroessner’s Colorado party is closely associated with red, the color resplendent on the scarves worn by their increasingly cult-like following), this archive tapestry offers a hypnotic portrait of the evolution of an authoritarian regime, demonstrating how nationalism and strong man “law and order” messaging morphs into a media monopoly and state-sanctioned violence.

Particularly striking interludes demonstrate the country’s interactions with the twentieth century’s most turbulent historical interludes—declassified CIA documents demonstrate U.S. interventions in Paraguay as part of the Cold War-era Operation Condor, while extracts from a 1970s British investigative documentary expose Stroessner’s personal protection of the Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele. Footage of Stroessner crowing a smiling beauty pageant contestant as “Miss Artillery Queen” or receiving bouquets from small children at parades, are contrasted with reports describing the torture of political prisoners and human rights abuses. Taken as a whole, the film is both a fascinating work of interventionist history-making and a stirring experimental study of power and control.

Since Berlinale, the film has screened at various festivals to wide acclaim. It heads next to Camden. In this interview, conducted at the Berlinale, Pereira spoke to Documentary about the film’s contemporary relevance, his journey into the archive, and the joy of the edit. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: What do you mean when you describe this film, made entirely from historical footage, as a “movie about the present”?

JUANJO PEREIRA: I began this project five years ago. During that period, I was studying in Argentina, and it was really another country with another politics. Now, I’ve come to the end of the film, and the right wing is coming to power again all over the world. Stroessner was democratically elected, and I can see how the same thing that happened in the Stroessner era is happening now. That’s why, to me, this is not a film about the past. It’s about the current international political moment.

D: How did your journey into the archives begin?

JP: A long time ago, I was in a small cinema in Buenos Aires and saw Chris Marker’s Le fond de l'air est rouge (1977). It’s an experimental film made entirely from archives from the 1960s–1970s, about how communists took power in different countries—in Cuba, in Chile, in Russia. I loved that movie, and became curious about working with archives in that way.

I began by looking for the first films made in Paraguay. Finding out how my country was represented in cinema became like an obsession. As I spent more time researching, I realized that there was more footage about the dictatorship than other areas of life. I began studying the process of how the dictatorship came to be, because I didn’t know anything. At school they don’t teach you about Stroessner, so in a way, I was beginning to learn about my country through the archives. The structure of the movie began to emerge from the archive itself. I didn’t write anything in advance.

D: How did you find the footage you use and how long did the research take?

JP: It took about six years of research. In the film, I work with these two points of view—the representation of the country that comes from inside Paraguay itself, and the representation which comes from the international media. We had to work from eight different archives: Paraguay, Argentina, Brazil, the United States, Belgium, the UK, France, and Germany. I think many of those archives didn’t even know that they had this kind of material. People don’t ask about Paraguay in France or Brazil, but these archives have a lot of material both shot in and about the country. We also found some things that we couldn’t watch because they only have one copy in negative and they can’t risk making the transfer to digital, so there were things we couldn’t use.

In Paraguay, there isn’t a national film archive. There's really just a guy in an office working for the government in Asunción. He has a social media page where he has been asking people around the country to send him old tapes. He does have a lot of material, but it’s in bad condition. I began to work with him, but it was not enough, so I started searching around the country, and around the world to fill those gaps. It was not a linear process, because new things were always appearing. We were making new discoveries all the time. I don’t think the team discovered everything that’s out there, I think there are probably more films hiding in some office in the countryside perhaps. I even found films in the garbage in Asunción.

D: It must be hard to know when to stop searching for footage, and to know when to start editing?

JP: I found my way to this process because I hate to shoot, but I really love editing. The archive gives you the opportunity to play. You can make 50 different movies, because the material is there. You don’t need to constantly reshoot. The editing process was also continuous. If we found some interesting material, we would work with it straight away. The first cut was four and a half hours and really messy, so getting that cut down was painful! Every image had to count because the licenses are expensive, and institutions charge per second.

As you go through the process, you get a better sense of what’s important and what isn’t. For instance, there’s a scene we include of a worker from the countryside filmed criticizing the police. That image is gold, because no one in Paraguay has seen this kind of scene before. There’s so little taped footage from these communities in the countryside. This sequence in which we see the villagers trying to form a cooperative system against Stroessner is so important for this particular moment in the country’s history. It was expensive, but it was worth it.

D: You also play with the footage, for instance using slow motion, running some footage in reverse and continually referencing the color red, especially with this red screen which appears in places. How did you use these visual techniques—and also sound design—to manipulate the footage?

JP: In the beginning, I wanted to manipulate the footage more, to scratch the film and work with an animator, but I ended up deciding upon a more abstract approach. I wanted to be disrespectful to the archive but with more subtlety. The first time we reversed the footage, we wanted to reflect how when Stroessner comes to power, there’s this regression. There are five moments in the movie where the screen turns red, and what I wanted to put in your mind there is this idea of red as the color of those 35 years of dictatorship. Like when you see a Rothko painting, I wanted to create a sense of the spectator being lost in color for ten seconds.

The sound designer Julián Galay was involved with the project from the beginning. He understood that I didn’t want the sound to be historically accurate but rather emotional. I wanted you to feel every cut through sound, as if you’re opening a new box or file—some of the sounds come from recordings of us actually opening the archive boxes, which have then been altered. I also chose not to do a voiceover, because we wanted to make the archive talk. We wanted to take these documents and squeeze them, and find their truth.

D: How do you expect the film to be received in Paraguay? And how do you think your film speaks to the current situation for filmmakers in the country?

JP: The situation in Paraguay is complicated. It's not a dictatorship anymore, but journalists are still being persecuted. You can say whatever you want, you’re not going to die, but there is persecution. We hope this film will get a good response, especially as it’s a bit more experimental in a way, but it’s possible that the government will respond badly.

I was told that there were Paraguayan press at the premiere, but at the end of the movie they decided not to talk about it. I’ve also heard of experiences from other artists in Paraguay, who have made art critical of the government which has been received badly. There are still people who are fans of the dictatorship, there’s even a football club named after Stroessner’s birthday, Club 3 de Noviembre. Every year, people go to stand in the square outside this football club and celebrate this birthday, and these public celebrations are allowed to go ahead.

However, there’s also a whole new generation of young people who want to talk about the dictatorship; in Paraguay we are hungry for our history. I co-run a festival, the Asunción International Contemporary Film Festival, where we have a laboratory for projects from Paraguay and every year we see how the projects are getting better. I’m not pretending that this film covers everything. It would be great for Under the Flags, the Sun to be a starting point for other filmmakers in Paraguay, because there are so many stories here. You could take the Mengele section and make a whole movie about him, or you could make a whole film about Operation Condor, or the coup d’etat, which we only cover briefly. I hope this movie will be a starting point for others.

Courtesy of Points North Institute