On Tuesday, November 11, 2025, long-time documentary cinematographer Erich Roland passed away after a nearly three-year battle with pancreatic cancer.

Best known for his work his work with Charles and Davis Guggenheim on films like The Johnstown Flood (1990), Waiting for Superman (2010) and He Named Me Malala (2015), Erich was also a fixture in Washington, DC—not just as a frequent Director of Photography on convention films for Barack Obama and Joe Biden, but also as the founder of DC Camera, a premier photo and video equipment rental company.

As Erich was living out his final months, he did something unusual: He made two short films.

The first one he posted on November 10, 2025, hinted at his impending demise. Set to the tune of Cat Stevens’s “Father and Son,” the piece reflects on a life well-lived—full of family, deep personal relationships, and professional accomplishments that few in life can ever hope to attain. That first film needed to be made to prepare the scores of friends, colleagues, and collaborators who knew him well.

During his years of treatment—a journey filled with surgery, chemotherapy, clinical trials, hopeful progress, and devastating setbacks—he had told no one outside of his immediate family about his illness. Indeed, his private turmoil belied the joy he projected to the public. Instead of pain and dread, his regular communications were full of images of stunning excursions into nature and the exuberant hijinks he enjoyed in his late-life romance with former high school classmate, Ines Nedelcovic. That was Erich through and through—private and inscrutable. Indeed, many people who watched that penultimate film didn’t quite know what to make of the hints dropped in it, as it lacked any context from all that had come before it.

His musical track selection for this piece, “Father and Son,” was fitting. Erich was born to a lineage of filmmaking storytellers. His father, Fritz Roland, was a cinematographer, first in Los Angeles and later in Washington, D.C., where he shot both dramas and documentaries. When Fritz could no longer work in the field, he and Erich’s mother, Ruth—a well-respected attorney—founded Roland House in 1985. The family’s mission was not simply to build a service-driven post-production facility, but rather to create a launching pad for new talent and cutting-edge technologies.

In practice, Roland House became an incubator to hatch untested ideas and creative schemes. Erich’s brothers, Franz (who predeceased Erich in 2023) and Hans, joined Roland House as executives, while Tanya, the couple’s only daughter, worked there as a colorist. But it was Erich, the youngest son, who was to strike out on his own, becoming the inheritor of his father’s cinematographic talents. His goal was not to match his father Fritz’s canny eye, but to distinguish himself from it. And so, he did.

Charles Guggenheim (1965’s Nine from Little Rock, 1968’s Robert Kennedy Remembered) was well into his long and storied career as a documentary filmmaker when, in 1989, he tapped young Erich, with whom he’d already been working on a few projects, to shoot what would become The Johnstown Flood. That short film, on the 1889 flood in Johnstown that drowned over 2,000 people, earned Guggenheim his third Academy Award. Their work together continued in D-Day Remembered (1994), A Place in the Land (1998), and Charles’s final film, Berga: Soldiers of Another War (2003).

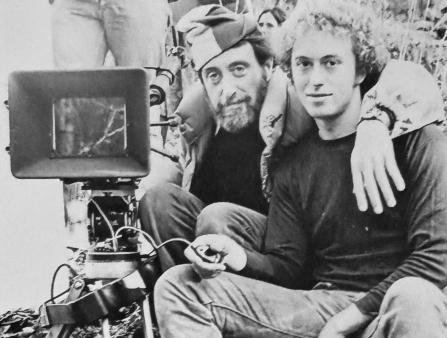

Fritz (L) and Erich Roland (R), circa 1978. Courtesy of the Roland family.

Nina Gilden Seavey (L), Paul Rusnak (C), and Erich Roland (R), shooting in Obninsk, Russia. Courtesy of Nina Gilden Seavey.

Charles’s daughter, Grace Guggenheim, who acted as her father’s producer, reminisced, “I grew up with Erich over the 18 years we worked alongside my father. Charles’s success clearly had to do with Erich’s ability and gifts.” Their relationship was symbiotic: the elder Guggenheim’s imprimatur allowed Erich’s natural talents and instincts to flourish throughout the 1990s as he became a highly sought-after and selective Director of Photography.

In 1999, family history repeated itself with the torch passing from father to son in the Guggenheim family as Davis, son of Charles, launched his own 20-year-long Director-DP partnership with Erich. Together they worked on critically acclaimed and industry-beloved films such as It Might Get Loud (2008), Waiting for “Superman” (2010), and He Named Me Malala (2015), among many other works—including convention films for Barack Obama (2012) and Joe Biden (2020).

Erich’s work encompassed more than documentary. Throughout his career, he worked in the camera department for films as disparate as Driving Miss Daisy (1989), Serial Mom (1994), and Double Jeopardy (1999). But his real love was living in the moment, often in the wild outdoors, lensing films with long-time documentarians such as Judy Hallet in her films American Buffalo: Spirit of a Nation (1998), Witness to Hope: The Life of Karol Wojtyla, Pope John Paul II (2002), and Stealing Time: The New Science of Aging. Turning Back the Clock (2010).

As for Erich’s and my work together, one could say that he did not come to it willingly nor voluntarily. Fritz had been a mentor to me since the earliest days of my career. In 1999, as I was searching for a new vision for my films, it was Fritz who persuaded his son to work with me. Erich worried about this shotgun marriage. I was known to be more than direct and a bit of a hot head. Neither of those qualities was Erich’s style. Ultimately, he deferred to his father’s cajoling and agreed to go on just one shoot with me. For the next fifteen years, Erich and I traveled the world together, making many films, including The Ballad of Bering Strait (2003), The Open Road: America Looks at Aging (2005), and the documentary comedy, A Short History of Sweet Potato Pie and How it Became a Flying Saucer (2006). Erich, like his father, had a wickedly wry sense of humor, and it showed in that film.

But it is perhaps Davis’s recollection that best sums up what we all felt in the years spent on planes, in production vans, and on the ground at dawn in the far-flung locations across the planet that we ventured to with Erich:

He was intense and quiet, and his work had a beauty and a delicacy. Other cinematographers hire large groups of people and spend twice as much time to do what Erich would do largely by himself, quietly, moving across the room, moving each light by himself, and the camera in just the right position.

When I watch movies directed by other people, I can usually tell when Erich is the cinematographer by the unique composition he brought to every frame and the very humanistic lighting he brought to his subjects.

He was kind, inquisitive, and just lovely to be around.

Erich was all those things—and he was a realist. He had found success in a world that cannot endure beyond one’s ability to work long, grueling hours and be fit enough to haul endless gear.

In 2004, Erich’s impulse to create a sustainable future for himself and his family—just as his father had—led him to found DC Camera. He focused on what he knew best: cameras and lighting gear. While continuing to shoot many films, he launched his business in a small warehouse in Arlington, Virginia.

Now, over 20 years later, DC Camera has grown to be one of the largest rental houses on the Eastern seaboard, providing equipment for documentaries, dramas, TV series, and even the weekend photographer. Like Roland House before it, DC Camera does not aspire to exist merely as a rental business. It thrives as a place of learning and growth, and even under the current owner, Tristan Loayza, who builds community by making gear accessible to many up-and-coming storytellers, especially those in the Mid-Atlantic region. Again, from father to son, the Roland legacy from Fritz to Erich, from Roland House to DC Camera, continues.

He was intense and quiet, and his work had a beauty and a delicacy. Other cinematographers hire large groups of people and spend twice as much time to do what Erich would do largely by himself, quietly, moving across the room, moving each light by himself, and the camera in just the right position.

Davis Guggenheim on Erich Roland

In late September, I was surprised to receive an email from Erich that had a plain subject line (“Pics and Such”) and an equally sparse subhead: “Story Time.”

In the message, Erich told me he was dying. He recounted some of the details as to how bleak his prognosis was. His words were straightforward and simple, as befitted his nature. But he wasn’t just informing me. He had a request: Would I assist him in completing two short films that would address how he wanted to say goodbye and how he wanted to be remembered? The first film was nearly done, save needing some additional photographs. The second one was less finished.

Over the next few weeks, Erich and I worked together as we had for all the years when he was shooting my films—talking, seeing, and reading images and turning them into emotional truths. Except now our roles were reversed. I was helping him articulate his vision so that he could find a way to express those truths for himself.

It was an honor that he asked me to work on this with him. But it was also the hardest and most surreal thing I have ever done. We weren’t dealing in some nonfiction abstraction. We were communicating about the rawest of human ordeals: facing death and summing up life and its meaning, and how we want to be remembered.

That second film, cut to a cover of The Beatles’ hit “In My Life,” was to be posted by his children, Austin and Rachel, several days after his passing. It came in the form of a musical supplication from the beyond: “Please do not forget me as you go back about your daily routines.” That prospect seems implausible—Erich’s contributions to the documentary world writ large and personally to the many people who knew him over his nearly five-decade career drove much too deep to leave us unchanged.

But that was Erich to the end: humble, quiet, private, and, like all great artists, striving to exercise control over any external elements that might somehow impinge upon his ability to communicate his vision. Erich was a master of understatement, and so he would be to the end.

Two weeks after Erich passed away, his daughter Rachel gave birth to a daughter: Lucy Erica Clark. And the cycle begins again.

Editor’s Note: Tanya Roland’s role in Roland House has been updated.