Kiro Russo's 'El Gran Movimiento': A 21st Century Response to Vertov's Symphony

The end of El Gran Movimiento, the hybrid second film by Bolivian director Kiro Russo, consists, quite literally, of all that came before. In a rapid-fire montage, images from prior scenes flash across the screen, first appearing just long enough for the viewer to recall each individually, then far too fast to even register. It’s the sound that makes the sequence, though: the montage unfolds to a salsa-inflected rendition of a snippet of the Alloy Orchestra’s score for Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera (1929). Condensing the entire film into a brief moment within a sequence that most clearly takes the form of a “city symphony” reminds us that this story is just one within La Paz, the film’s setting and the home to nearly seven percent of Bolivia’s population. In doing so, El Gran Movimiento forces us to rethink how the prior century’s celebrations of urban life apply to the 21st century’s globalized city, where the exploited, homeless, and outcast lack the collectivity that defined the masses in the classic city symphonies of the 1920s and ‘30s.

If one treats the term strictly and historically, “city symphony” films are relatively small in number. Only a handful of films from the 1920s and early 1930s, most of them shorts rather than features, take a “symphonic”—denoted by extensive reliance on montage—approach to depicting the happenings of a city; from waking to work to evening leisure, across a single day. Still, the genre occupies an outsized importance in film history because these films lie at the nexus of so many significant discourses. They are documentary films showcasing the reality of industrializing metropolises (and occasionally smaller cities) with then-new technology; they are avant-garde films that shun theatrical or literary modes of filmmaking in favor of something closer to other avant-garde art movements; they are vectors for political ideologies on both the left and right. More liberally, the city symphony is a tendency also recognizable in narrative fiction, such as Do The Right Thing. Perhaps because of this variety—and it should be further noted that the city symphony need not even be laudatory, as Jean Vigo’s À propos de Nice demonstrates—the phrase and the ideas associated with it have left an imprint on cinema that continues to shape the way we think about certain films.

Man with a Movie Camera is a natural film to invoke for the purpose of guiding a viewer’s thinking because it is, though not the first, certainly the most famous and studied “city symphony” film. For all of its other concerns (crafting a cinema divorced from the influence of literature or theater, arguing for a utilitarian purpose for filmmaking that could fit alongside factory work), it is an intensely political depiction of city and society. Ironically, it was shot in not one, but three cities—Moscow, Kyiv, and Odessa—although only the occasional landmark, such as the Bolshoi Theater at the end of the film, gives us any indication that this is not a single, real space. What it envisions instead of unity of space is the unity of purpose. The film covers a day in the life of this imagined mega-city for street cleaners, factory workers, ironworkers, switchboard operators, tram conductors, tailors, cigarette box makers, and fillers, and, of course, filmmakers, all of whom are working together to build a better future. There is, in Man With a Movie Camera, an understanding that everyone is everyone else’s neighbor, and that all neighbors share a purpose.

Vertov communicates this unity with his extensive use of graphic matches and cross-cutting, which link together seemingly disparate ideas. In the film’s second of six sections, Vertov cross-cuts one woman waking up and preparing for work with the work of street sweepers nearing the end of their shift before the streets are overtaken with pedestrians and public transit. Indeed, the streets soon start to fill up. Whether the people and vehicles are moving in the same or opposite directions, in a frame neatly bifurcated by a streetlamp, or in a more disorganized one, the feeling conveyed is not of chaos but of harmony. People walk in an orderly fashion, or else Vertov superimposes several shots or divides the frame so his subjects can move freely across the screen without needing to worry about crashing into one another. The city itself provides no obstacles or conflicts, it only facilitates community and vision.

If Vertov’s symphonic ode is to a city built by and for people, rather than despite them, Russo’s is to a city all but indifferent to its inhabitants. It follows a young man, Elder, who has spent a week walking the roughly 250 miles that separate Huanuni from La Paz, where he and his coworkers accept the limited work they can get while airing their grievances about unsafe conditions and wage theft. But the realities of exploitation are antithetical to the goals Vertov envisions. The residents of La Paz in El Gran Movimiento are not united by a shared goal of societal improvement but instead atomized units looking, in some instances, merely to survive, and in others, to get richer, even at the expense of others: we watch in the film as workers who load the trucks and move crates berated for not being fast enough as they perform what is literally backbreaking work and then short-changed after the fact.

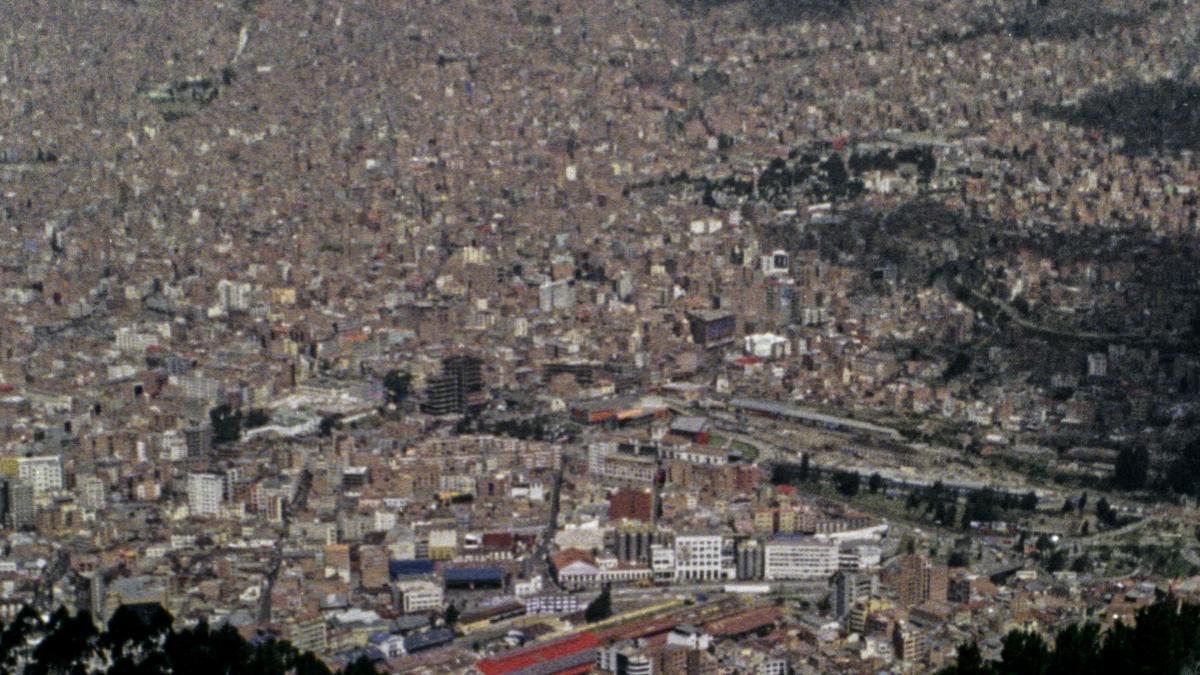

Indeed, El Gran Movimiento portrays the city not as an entity defined by its people but as a pre-existing one in which people try to fit. The film opens with an overhead extreme wide shot of La Paz, buildings all but indistinguishable from one another, slowly zeroing in on one segment as the sounds of traffic and construction grow on the soundtrack. The camera, in successive shots, continues to examine the architecture and space of the city, with the only indication of human life being by implication of the city noise and, eventually, the distorted likeness of a person seen through a series of convex and concave reflections. We then cut to a wall covered, time and time again, in flyers, brochures, posters, and more. This image, of countless promotions torn apart or pasted atop one another, competing with each other for the attention of whoever happens to be looking, captures the atomized, cutthroat competitive nature of 21st-century urban life as aptly as any other. Only after the title card, when the film takes us to a miner protest, do we see an identifiable face.

In his criticism of the city symphony film, John Grierson rhetorically asked, “What more attractive (for a man of visual taste) than to swing wheels and pistons about in the ding-dong description of a machine, when he has little to say about the man who tends it? And what more comfortable if, in one’s heart, there is avoidance of the issue of underpaid labor and meaningless production?” But with the images of a protest and those that follow, El Gran Movimiento highlights that missing side of the city. Elder is sick, and although the doctors in the film cannot determine exactly why (one suggests that “rest” may help), what ails Elder—a miner with a brutal cough, little money, and no comfortable place to sleep—are the failings of his society to provide him with the bare necessities that could keep him healthy. The inability of the doctors to see this speaks, metaphorically, to the invisibility of the exploited inhabitants of the neoliberal city and, following Grierson, to the way the exaltation of the city invisibilizes the man who tends the machine (or, as it is here, swings the pickaxe).

The invisibility of the exploited worker finds its counterpart in the invisibility not of the wealthy, but of their production. At one point, Elder and his friends take a gondola over a large house with a swimming pool and dream aloud about owning one like it; but who owns this house, and how they got so rich while others are so poor, is unclear. Production, in fact, is largely unseen in El Gran Movimiento, which instead highlights commerce. The locale that defines El Gran Movimiento instead is the market. But the market is a locus where wealth is exchanged much more than it is created; certainly nobody is buying mansions with private pools off of what they make selling vegetables. That wealth comes from some unseen means, and goes to unseen persons.

This too finds its emphasis in El Gran Movimiento’s final scene. As the Latinized arrangement of the Alloy Orchestra tune from Vertov’s film begins, we at last see production, but that production is automated; there is no worker around to reap the fruits, only some owner of capital beyond the frame, to further accrue it. As the scene moves to the market, Russo shoots several close-ups of hands. These hands, however, are not working, like those in Man With a Movie Camera. They are transacting. Vertov shows us hands as they work; Russo shows us hands exchanging currency. There is no city, and therefore no future or society, to build. There is only the unfixable present to inhabit, to scrape by in, This difference, highlighted by the music, informs us of the distinction between the utopian vision of the early years of the USSR and the hard reality of contemporary La Paz.

What exactly has gone wrong is not immediately apparent, but returning once again to Man With a Movie Camera provides a clue. Despite his written proclamations that the camera eye is superior to the human eye, Vertov was not a techno-utopian. As the film moves toward depictions of work in its middle segments, people, in accordance with the general pro-Taylorist sentiment of the times, are shown working hard, but not quite mechanistically. While their hands labor in an increasingly frenetic sequence depicting cigarette boxing, switchboard operation, and ironwork, and more, Vertov makes a point to also show smiling faces. But Vertov finds value not only in the mechanistic components of man but also the humanistic elements of machines. Near the end of the film, the camera itself is anthropomorphized, as stop motion makes it appear to dance. This antic is cut to make it look like an audience is laughing, inviting us not to take it too seriously, but the comedic approach only reinforces the harmony the film finds between organic and synthetic.

Technology in El Gran Movimiento is alluded to, not seen. The opening sequence uncomfortably invokes the specter of surveillance; the close-ups of tendered currency might remind us that the vast majority of transactions, especially high-value transactions, are purely electronic; even the centrality of mining to the story, something far rarer in a story taking place in the global north, is a reminder that nations full of exploited laborers sustain the access to cheap products enjoyed by more comfortable white-collar society. Whatever harmony Vertov envisioned between man and machine is absent here; technology is wielded by one unseen group of people, thanks to the exploitation of another. By the end, then, Russo invokes Vertov’s vision as a contrast to his reality. Rather than finding harmony with the proletariat, the technology of the present day has conquered them.

El Gran Movimiento is currently playing at the Francesca Beale Theater at Lincoln Center in New York City.

Forrest Cardamenis is a film critic based in Astoria, New York. He received an MA in Cinema Studies from NYU, and his writing has featured in a variety of publications, including Reverse Shot, MUBI, and Filmmaker.