The 73rd San Sebastián International Film Festival, held from September 19–27 in the picturesque Basque resort city, reaffirmed its standing as one of Europe’s most vital cultural crossroads. A festival that has long combined auteurist prestige with an openness to new cinematic languages, this year’s edition underscored its dual identity as both a glamorous showcase for Spanish and international talent and a fertile laboratory for nonfiction and hybrid forms.

The Golden Shell, the festival’s top honor, went to Sundays (Los Domingos) by Alauda Ruiz de Azúa, marking a significant victory for Spanish female filmmakers.

Meanwhile, José Luis Guerín’s documentary Good Valley Stories earned the Special Jury Prize—an outcome in keeping with San Sebastián’s long-standing commitment to boundary-pushing nonfiction.

Beyond its main competition, the festival spotlighted a robust slate of restorations in the Klasikoak section, including a 4K version of José Luis Borau’s 1975 film, Poachers (Furtivos), and a quartet of restored Basque medium-length films completed at Bologna’s L’Immagine Ritrovata. The result was an edition that bridged past and present, pairing contemporary social urgency with acts of historical recovery.

A Festival With a Conscience

Following the political ripple effects of the “Venice4Palestine” initiative at Venice, San Sebastián also took a public stance of solidarity. Pedro Almodóvar, among others, delivered impassioned statements in support of Palestine, while Donostia Award recipient Esther García wore a “Stop Genocide” badge in the watermelon colors of the Palestinian flag. More importantly, protesters gathered in large numbers almost every day in and around the Kursaal, showing their support for the Palestinian cause.

These gestures added moral texture to a festival that often defines itself through its political conscience, an attitude also visible in its selection of films this year, many of which dealt with displacement, justice, and environmental degradation.

The entire festival mirrored this climate of engagement, from press conferences to industry events. San Sebastián was among the few major European festivals to take a clear stance on the Israeli-Palestinian crisis: the topic surfaced repeatedly during Q&As and even at press events for more commercial films. International guests such as Jennifer Lawrence publicly condemned the ongoing genocide, whilst Angelina Jolie used her platform to criticize Donald Trump’s recent censorship moves. Within this atmosphere of open political discourse, the documentary co-production forum Lau Haizetara once again proved to be a cornerstone for project incubation and professional networking. Speaking to Documentary, festival veteran Silvia Hornos, who heads the forum, describes its evolution as a leap “from a trans-Pyrenean gathering to a truly international catalyst for creative, high-impact projects.”

The forum follows the well-oiled three-step structure—comprising workshops, pitching sessions, and one-on-one meetings—that many leading European co-production platforms have successfully adopted. This year’s selection of 16 projects, Hornos says, underscored “diversity, innovation, and impact potential” as guiding principles. Featuring projects from Latin America to the Middle East, the lineup reflected the forum’s expanding scope and the increasing demand for transnational storytelling. “We believe the best stories can come from anywhere,” Hornos adds, “as long as they touch the soul.”

Such words encapsulate the ethos of San Sebastián itself, a festival that is at once regional and global, rooted in Basque identity yet open to the world. This spirit was reflected vividly in the diversity of projects pitched at Lau Haizetara. Some grappled directly with urgent geopolitical realities, such as Gaza Sunbirds (Belgium-U.K., dir. Flavia Capellini), which follows a team of war-amputee cyclists in Gaza as they transform loss into resilience, or Wolf Game (U.S.-Palestine, dir. Patricia Echeverria Liras), a daring essay-doc linking land conflict in the West Bank to digital colonisation in the metaverse. Others confronted contemporary forms of gendered and digital violence, such as No Consent (Spain-Italy, dirs. Montserrat Bover Rabionet and Núria Vilà Coma), which traces the fight of three women against the online trade in non-consensual imagery.

Equally emblematic were projects rooted in the festival’s own soil yet resonant far beyond it. For example, Butterflies (Altxaliliak, Spain-France, dir. Maia Iribarne Olhagarai) celebrates queer, rural Basque performers who reclaim tradition through music, latex, and the Basque language itself. Meanwhile, A Thermomix in the Desert (Spain, dir. Marta Guillén) turns inward, blending animation, archival imagery, and social-media footage to map a generation’s exhaustion and search for authenticity in the digital age.

The entire line-up illustrates the festival’s guiding paradox: an event deeply anchored in local culture that continually opens itself to global urgencies, using documentary storytelling as a meeting ground for identities, struggles, and imaginaries from every latitude.

Good Valley Stories.

Flores para Antonio.

In-I In Motion.

Good Valley Stories: José Luis Guerín’s Poetic Chronicle of Everyday Barcelona

Returning to the competition 24 years after Work in Progress (En construcción) (2001), José Luis Guerín once again set his camera on the outskirts of Barcelona to observe ordinary life in Good Valley Stories, a deeply humanist nonfiction feature that earned him this year’s Special Jury Prize. Shot over three years in Vallbona, a semi-rural district bordered by rivers and railways, the film captures the coexistence of old farming families, new immigrants, and the slow encroachment of urban development.

There’s no conventional script or imposed narrative. Guerín begins with black-and-white Super 8 images—an almost nostalgic gesture toward the roots of observational cinema—before allowing the film to unfold through interviews, neighborhood gatherings, and quotidian rituals. He often reveals his own voice in dialogue with the non-professional participants, foregrounding the creative process itself. What emerges is not only a portrait of a place, but also a portrait of collaboration, where the filmmaker and the community build meaning together.

Vallbona becomes a microcosm of transition, a space where environmental and social questions are intertwined. An elderly man recalls the ruins scattered throughout the neighborhood, while another laments the arrival of new apartment blocks and the fading of memories. Together, they form a mosaic of longing and endurance, evoking both the vitality and fragility of working-class life.

By refusing dramatic artifice, Guerín achieves a different kind of drama—one that captures the slow, tactile rhythm of everyday existence. The film’s two-hour runtime feels immersive rather than indulgent, allowing the viewer to sense the emotional bond that has developed between the director and the subjects. The film’s understated simplicity belies a profound reflection on how communities adapt, vanish, and are reborn under the pressures of modernization.

Arriving close to 25 years after Work in Progress, Good Valley Stories confirms Guerín as one of Europe’s last great chroniclers of the everyday. His cinema, at once intellectual and intimate, continues to blur the line between documentary and poetry. His work is proof that, in a world of accelerated storytelling, patient observation remains a radical act.

Flores para Antonio: Alba Flores in Search of a Father and a Myth

Despite playing out of competition, Flores para Antonio, directed by Elena Molina and Isaki Lacuesta, was among the festival’s most talked-about titles. The film invites actress Alba Flores (Money Heist) to journey into the mythos of her own lineage. The result is a moving excavation of Spain’s most iconic artistic dynasty: the Flores family. As seen on screen, their legacy blends art, tragedy, and an almost sacred familiarity with the public.

The film’s labyrinthine structure mirrors its subject. Here, memory is a maze, grief, a ritual of return. Molina and Lacuesta’s documentary reconstructs the life and death of Antonio Flores, Alba’s father, the musician and actor who died in 1995 at 33 from a fatal mix of alcohol, barbiturates, and despair. Through intimate interviews with her mother, sisters Rosario and Lolita, and countless family friends, Alba revisits a shared history that had long remained unspoken.

“I wasn’t aware that I’d never talked to my family about this,” she admits on camera. “We did it for the first time while filming the documentary.” That candor transforms Flores para Antonio from mere homage into an act of emotional reckoning. The filmmakers weave archival footage, home movies, concert fragments, and clips from Antonio’s films, Colegas and Blood and Sand, into a dense visual tapestry. The result is less a chronological biography than a living séance—a dialogue between generations mediated by cinema itself.

Lacuesta, known for hybrid works like Between Two Waters (2018), brings his characteristic fluidity between fiction and reality, while Molina ensures the film retains its emotional focus. Together, they create what feels like a familial and national mirror, an exploration of Spain’s popular culture that shuttles between fame and authenticity.

The directing duo resists sensationalism, instead favoring a tone of reflection. As Lacuesta observed during the press conference, “The level of exposure the Flores family had before social media was like that of a royal household—except everything about them was real.” In that statement lies the tension at the heart of the film: public myth versus private truth. Flores para Antonio restores both.

In-I In Motion: Juliette Binoche Turns the Camera on Herself

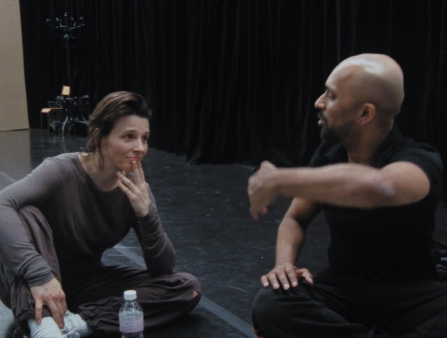

With In-I In Motion, Binoche makes her directing debut, offering a meticulous chronicle of the 2008 stage collaboration she created with British dancer-choreographer Akram Khan. The project, titled In-I, was originally conceived as a daring fusion of dance and theater—an experiment in vulnerability for both artists. Seventeen years later, Binoche reassembles rehearsal footage, stage recordings, and behind-the-scenes material into a raw, revealing documentary.

Structured in two halves, the 156-minute effort first immerses viewers in months of rehearsal within stark, black-draped studios. There are no interviews or explanatory voiceovers. There’s only the physical and emotional labor of creation. Binoche and Khan push each other beyond their comfort zones, negotiating intimacy and exhaustion in equal measure. When the finished performance finally unfolds, it feels earned: a cathartic synthesis of movement and emotion, enhanced by Anish Kapoor’s minimalist set and Binoche’s sister Marion Stalens’s camera, which moves fluidly with the dancers.

The film’s subject—the anatomy of collaboration—is deceptively simple. Yet in showing two accomplished artists learning new disciplines from scratch, In-I In Motion becomes an essay on humility and trust. The lack of retrospective commentary keeps the work immediate, unfiltered, and surprisingly tense. There are moments when rehearsal frustration borders on confrontation, only to dissolve in laughter—an authenticity rare in celebrity-driven projects.

That said, the film’s extended runtime and absence of contextual framing might prove challenging for casual viewers. But for those attuned to the rigor of performance-making, Binoche’s approach feels appropriately ascetic. She understands that creativity often emerges from discomfort. Her camera captures the unglamorous in-between moments—failed takes, bruises, awkward silences—that reveal artistry as a process rather than a pose or a result.

In the final segment, as the lovers onstage meet, separate, and reunite beneath flickering light that evokes the glow of a movie projector, Binoche returns to her native medium: cinema. The documentary thus completes a circle. What began as an act of artistic exposure becomes a reflection on how we inhabit our bodies, our work, and our memories.

Copper: Nicolás Pereda Mines the Absurdity of Survival

In Copper (Cobre), Pereda delivers one of his most elliptical yet politically resonant works to date. Presented in the Latin Horizons sidebar, the film blends fiction and documentary to depict a small mining town where every life revolves around copper—its extraction, its toxicity, and its metaphorical weight. Working in his familiar docufiction mode, Pereda stages scripted situations inside a world that feels observed rather than fabricated, pursuing not realism but veracity—an atmosphere where invention grows organically from lived detail.

The story follows Lázaro (played by Pereda regular Lázaro G. Rodríguez), a weary miner afflicted with breathing problems who obsesses over obtaining an oxygen tank. His futile quest, as bureaucrats and doctors dismiss his suffering, becomes a deadpan allegory for systemic neglect. A body discovered by the roadside in the opening sequence barely stirs anyone’s curiosity—a grim symptom of collective resignation.

True to his method of collaborative creation, Pereda develops his scripts around a stable ensemble he has worked with for years, allowing roles to adapt to the performers rather than the other way around. He stages this slow corrosion of empathy with his usual formal restraint. Long static takes, off-screen action, and deliberately minimal performances create an atmosphere of quiet suffocation. Yet within that stillness, moments of surreal levity emerge—particularly a scene in which Lázaro and his aunt rehearse a date with a corrupt doctor. Their rehearsal plays half like a strategy session, half like a skit, and it carries the offhand, observational charge that runs through Pereda’s work—performances that feel barely performed.

Visually, Copper oscillates between austere interiors and luminous exteriors filmed in the dying light of dusk. Cinematographer Miguel Tovar captures a palette of browns, greens, and muted golds, invoking both the beauty and toxicity of the environment. Pereda’s minimalism becomes an ethical stance: by withholding spectacle, he implicates the viewer in the act of seeing what the town refuses to acknowledge.

The film’s title substance thus works as both material and metaphor—a conduit of survival and suffocation alike. Copper doesn’t shout its politics; it murmurs them through rhythm, absence, and repetition. In doing so, Pereda crafts a haunting parable about the invisible violence of economic dependency and the quiet endurance of those trapped within its circuits.