“Truth, you build it,” declared Claire Simon emphatically from the Ji.hlava stage as she presented Writing Life – Annie Ernaux Through the Eyes of High School Students at the Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival (October 24–November 2, 2025). Now the largest documentary gathering in Central and Eastern Europe, as measured by the number of selected films and reported attendance, Ji.hlava engages in such truth building, serving as an open platform for dialogue across Czech society.

Nestled in Jihlava, a small industrial town in the Highlands between Bohemia and Moravia about two hours south of Prague, in November the festival boasts a gothic ambience that filmmakers like Tsai Ming-liang grow particularly fond of. Following last year’s retrospective and masterclass, the Taiwanese master returned to Jihlava to shoot a new installment of his Walker series with students from Prague’s FAMU, premiering it at the festival. “He really liked the foggy atmosphere,” festival director Marek Hovorka tells Documentary, “so he proposed to come back.”

Hovorka founded Ji.hlava while he was still in high school—and he has remained at its helm ever since. Now in its 29th year, the festival retains its lively and youthful charm. Venues are within easy reach; sipping cappuccinos, many of the stylish young crowds come from hip Prague districts, as one attendee remarked. The festival continued its extended 10-day format introduced last year, which saw public attendance grow by around 20%, according to Hovorka. It also extends online for two additional weeks, with a digital platform available to visitors, guests, and industry professionals—generating 37,000 streams last year.

This year’s program reaffirmed Ji.hlava’s commitment to supporting emerging filmmakers. The First Lights section now focuses exclusively on feature-length debuts, while Opus Bonum highlights work from more seasoned filmmakers, such as Peter Mettler’s seven-hour odyssey, While the Green Grass Grows: A Diary in Seven Parts, and Yi Cui’s To Alexandra. Czech Joy—the festival’s national competition—expanded to include international co-productions such as Vitaly Mansky’s ode to the Ukrainian city of Lviv, Time to the Target, which secured the top prize in that category.

The national broadcaster, Czech Television, and the main public financing body, the Czech Audiovisual Fund, remain key partners for Czech documentaries. The festival’s industry platform—the Ji.hlava New Visions Forum & Market—hosted “Czech Joy in the Spotlight,” selecting ten Czech documentaries from the current Czech Joy lineup for potential international distribution and sales agents—seven of which were supported by Czech Television and Czech Audiovisual Fund. The industry program also features a vibrant pitching forum showcasing projects from Europe, the United States, and, since last year, East and Southeast Asia, deepening the festival’s cultural ties with the region.

Ji.hlava’s most consistently strong slate continues to focus on socially and politically minded films. Natalia Koniarz’s Silver, which deservedly took home the Opus Bonum prize, is a complex tapestry of colonial history, poverty, and extraction. Set in Potosí, Bolivia—one of the world’s highest cities—and its neighboring mountain, Cerro Rico, the Polish director follows miners as they search for silver veins in a dark labyrinth of gray rock. Both the city and the mountain are renowned for their deep connection to silver mining. In Silver, miners’ children are taught in their makeshift school that the Spanish colonialists forced Indigenous people to work in the mines for up to half a year, without rest, resulting in 8 million deaths since colonial times.

The film is an immersive snapshot of the physical and psychological toll of the grueling conditions. Marcin Lenarczyk’s sound design creates layers of the haunting legacy of the mines. Balancing the nondiegetic clang of the hammer, the sizzling whisper of the burning dynamite, and the rhythmic creak of the coarse rope as it is being pulled up, the film’s soundscape also leans into ghostly whispers and eerie strains. Each year, hundreds of miners perish. “We get to live till our 40s,” remarks one miner. Cinematographer Stanisław Cuske zooms in on miners’ calloused hands and children’s innocent eyes, creating a poetic vision of desperation.

Silver.

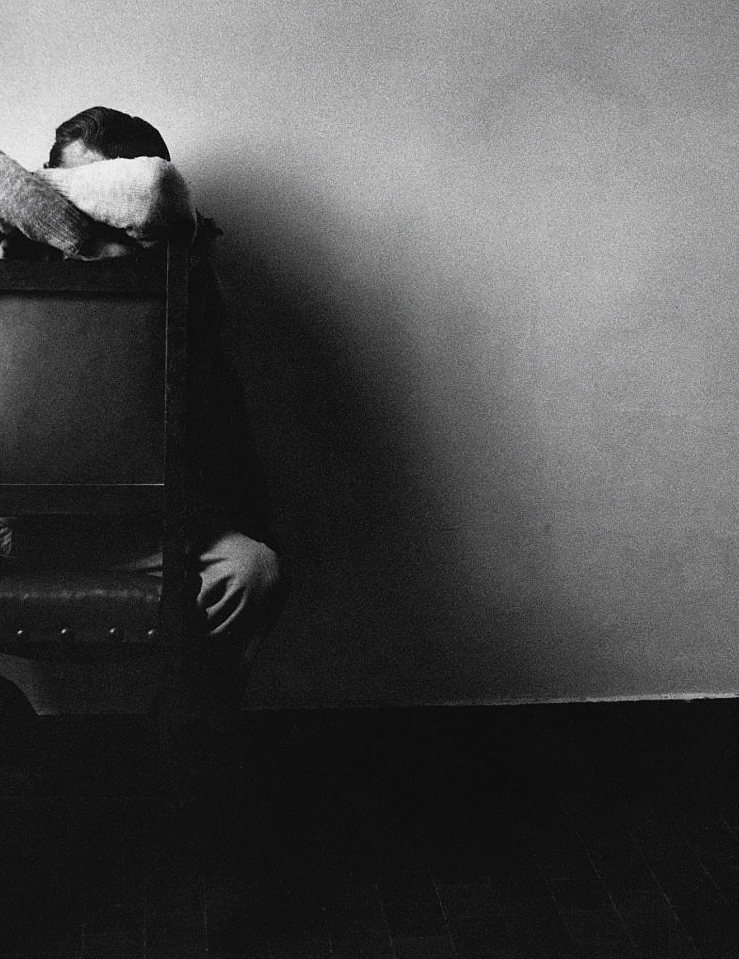

Claire Simon (L) and festival founder and director Marek Hovorka (R) in Ji.hlava’s customary filmmaker photo from the stage. Image credit: Jan Hromádko

Virtual Girlfriends.

A Polish, Finnish, and Norwegian co-production (with Paweł Pawlikowski credited as executive producer), Silver opts out of the character-driven style of documentary. Instead, Koniarz adopts a fly-on-the-wall approach to create a collective portrait of the poverty-stricken region. The film successfully weaves the daily grind into its surroundings: particles of silver meshed with sweat glowing in the dark; the headlamps casting beams across glistening rock; the shifting palette of darkness as our eyes adjust.

The film also records candid conversations between miners and others. In one striking scene, we leave the mine’s depths for another kind of descent—to a strip club, where a tired miner spends his hard-earned cash seeking a moment of human connection. “Loneliness is eating you up,” a dancer remarks over the loud music. Later, another young miner decides to leave Potosí for good and instructs his brother, barely 12, that it is his turn to “become a man in the family.” These unguarded exchanges, whether spontaneous or staged, fold naturally into the film’s larger mosaic. The film closes with an intertitle: “Without silver, there would be no mirrors, no electronics, no cameras, no artificial intelligence.” Silver is not just a bygone treasure—it will also be desired in a future powered by multinational AI corporations.

The Czech lineup was led by Barbora Chalupová’s Virtuální přítelkyně (Virtual Girlfriends), the festival’s opening film, which explores the lives and loves of three female creators of the OnlyFans platform. Chalupová, who previously co-directed Caught in the Net (2020), a groundbreaking exposé of online predators, turns her camera toward adult creators in a comparatively disappointing effort. We watch women mount their iPhones on a tripod, dressed in lingerie, making cash while everyone is sleeping. At a slow and meticulous pace, Chalupová sets out to reveal how “unglamorous” their work is. Her protagonists plan content, scout locations, and strategize ways to stay relevant in the transactional world of male whims and algorithms.

In an attempt to demystify modern digital sex work, the film walks a tricky line, occasionally slipping into scripted territory. In one scene, an influencer asks her partner whether he minds her line of work; he replies that he has no regrets. Shot after dark, in a beautifully lit and composed mise-en-scène, the sequence uses shot-reverse-shot framing to capture what appears to be “a candid” love talk. Later, the same influencer discusses her son’s future with her friend. Borrowing editing techniques from fiction, the two women sit in a wide shot before the film conveniently cuts to a close-up of the influencer, who hesitates for a beat before saying that her son is too young to know.

Although the tension between authenticity and performance is unbalanced, the real frustration of Virtual Girlfriends lies in its avoidance of probing deeper into the mechanisms of transactional desire. Instead, it settles for a self-serving narrative that reproduces the very surfaces of performance it aims to expose.

Resilience.

The Beauty of the Donkey.

Head of Industry Jarmila Outratová (L) and Khavn de la Cruz (R). Image credit: Jan Hromádko

Many films across the festival’s sections explored the kinship between humans and the non-human world. One of the strongest contenders was Tomáš Elšík’s Při zemi (Resilience). Shot near Jihlava, this observational documentary is both a physical and metaphysical quest into the relationship between humans and nature. The film follows Klára, who works for the Czech Society of Ornithology, and Pavel, who restores wetlands damaged by drought and deforestation. As they go about their days, seasons change. The lake freezes over, and fog blankets the forest.

Midway through the film, Klára discovers that birds, including an endangered white-tailed eagle, have been poisoned by carbofuran, a highly toxic pesticide banned in many countries. Elšík, also the film’s cinematographer, closely follows the process as Klára’s dogs locate the bird’s corpse and determine the poisoning’s source . Eventually, Klára and her team identify the perpetrator. Elšík reenacts the search for the poison, and then to the courtroom, where the culprit is sentenced to three years’ probation. Unlike the performances in Virtual Girlfriends, in Resilience the reenactments emerge organically from the film’s dramatic tension. After Klára discovers several poisoned birds and her team identifies carbofuran as the cause, the previously unfilmed search and courtroom hearings are restaged to provide narrative closure.

Meanwhile, Pavel, also accompanied by a dog, shares his environmental motto of cooperation rather than domination. “I don’t fight the drought, I cooperate with it,” he muses. Inspired by the ecological writings of American phenomenologist David Abram, Elšík captures the cyclical, reciprocal relationship his protagonists maintain with nature. In winter, Pavel observes changes in the fauna and flora; in spring, he plants young bushes. Interspersed with their personal narratives are Elšík’s meditations on life and matter that recall Terrence Malick’s Voyage of Time: extreme close-ups reveal snowflakes and insects down to their molecular level, while the blazing eye of the Earth pulses under eerie, atmospheric music.

Reenactment was also powerfully realized by Swiss Albanian filmmaker Dea Gjinovci in The Beauty of the Donkey. Conceived as a family ethnography, the film follows Gjinovci’s father, Asllan, as he returns to his native village in Kosovo in search of his mother’s remains. Gjinovci reconstructs her father’s house by building a wooden carcass of it, doubling as a stage draped with long white curtains over nonexistent windows. She casts a young Asllan, his mother, and other family members, letting them reenact fragments of Asllan’s childhood, while the real Asllan watches from a quiet distance.

The film’s layered structure mirrors the complexity of memory and the power of oral history. As the actors sit by the fire in period clothes, it becomes easy to forget that what we are watching is a reconstruction; it feels lived, not staged. At times, Gjinovci blurs the line between reenactment and reality, allowing her father to step into the performance himself. In the process, the scenes become meaningful as meditations on the fragility of home amidst war.

The film’s layered structure mirrors the complexity of memory and the power of oral history. As the actors sit by the fire in period clothes, it becomes easy to forget that what we are watching is a reconstruction; it feels lived, not staged.

On The Beauty of the Donkey

The brutal genocide of the Albanians revisited in Gjinovci’s film happened barely 30 years ago, and it was impossible not to think of the current devastation in Palestine and the war in Ukraine. Ji.hlava’s programming also reflected these connections. In its Constellation section, the festival presented I Shall Not Hate (2024). Based on a memoir of the same name, the film recounts the gut-wrenching story of Palestinian doctor Izzeldin Abuelaish, who lost three daughters to shelling in 2009 at the height of the Israeli assault. Abuelaish attended the screening and later spoke at Ji.hlava’s Inspiration Forum. With the Czech state’s continued support of Israel, the invitation of Abuelaish felt like a timely statement of solidarity. Ji.hlava's largest screening theatre—Horácké divadlo, with its 313 seats—was packed to the brim, and the audience rose to its feet as Abuelaish walked onto the stage.

The festival trailer, commissioned from Ukrainian veteran filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa, carried a similar weight. In it, residents of Dnipro descend underground, going about their day on the metro. The camera lingers outside the carriages before slipping inside the train. At one point, it stops at a station aptly named “Freedom Avenue”; the doors keep opening and closing until the screen turns black. Watching this minimalist trailer several times a day effectively translated the fatigue of war coverage and the numbing mundanity that comes with it. Each time, I thought back to Claire Simon’s words and her reminder that truth is not a given, but something actively constructed.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Winter 2026 issue.