Following the premiere of Man of Aran (1934), director Robert J. Flaherty described the relationship between the people of the Aran Islands, off Ireland’s west coast, and the sea that swaddles them, in combative terms. According to his biographer Arthur Calder-Marshall, Flaherty said that Araners don’t just live by the sea, they are forced to “fight it” to survive.

Half a century later, the Irish filmmaker Bob Quinn took a more complex view of this dynamic than Flaherty’s Manichean image of elemental struggle. For the people of “peripheral,” Irish-speaking, western coastal regions like the Aran Islands and their neighbour, Connemara, the sea is no barrier nor beast to be slain but a bountiful and open conduit of sustenance, trade, communication, and culture.

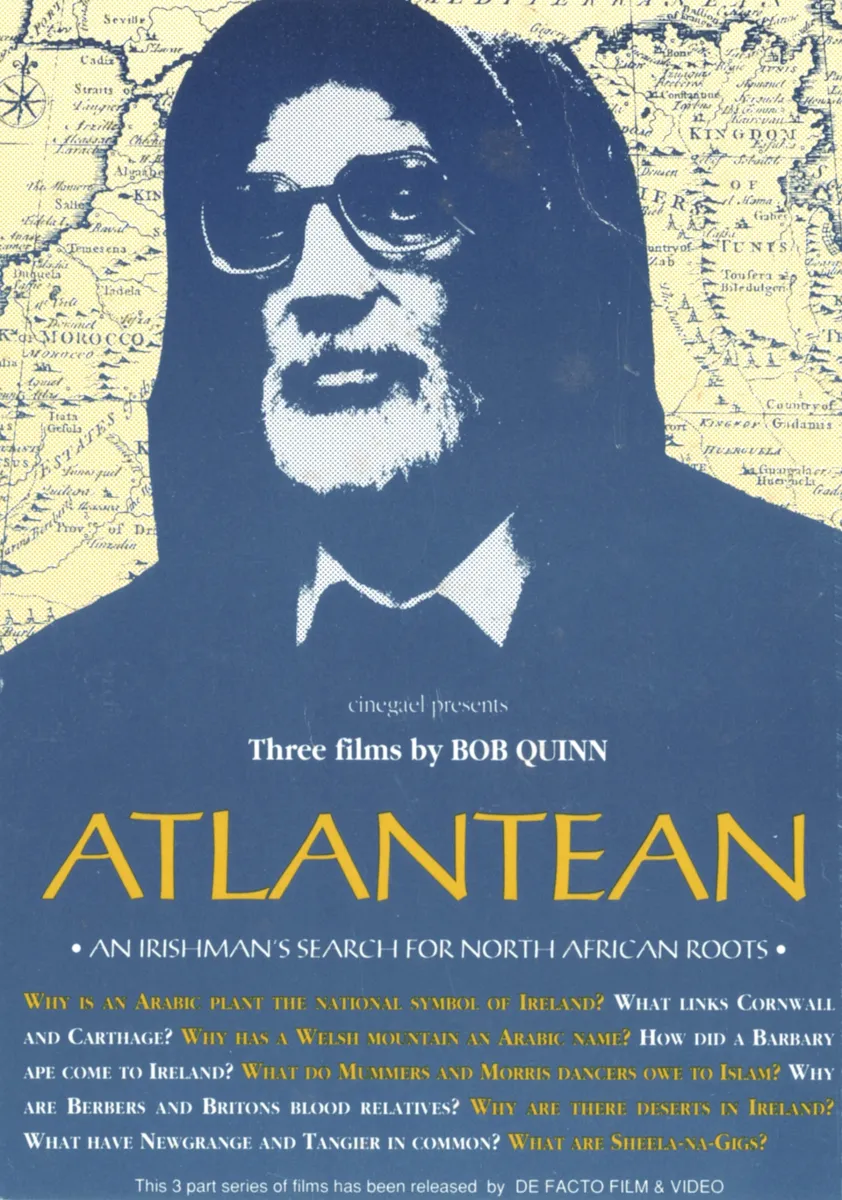

This more generous estimate would also take a suitably proliferative shape. Quinn would eventually transmute years of study into a book, The Atlantean Irish (1986), and the three-part documentary Atlantean. Aired on RTÉ in 1984, this trilogy is subversive in its ideas and form, a talisman of Quinn’s commitment to filmmaking as a communitarian and experimental art form.

Over the past year, Quinn’s 90th year and his nearly 60 years of work in film and television were marked with a new collection of his writings, Count Me Out, edited by his son Toner Quinn, and several events and screenings around Ireland. These have been celebrations of a life of extraordinary productivity, and occasion this consideration of his influence. Alongside directing over 50 short films, features, and series, working mainly in documentary and with a dizzying array of subjects and styles, he has a significant literary output with several novels, a memoir, and short and longform cultural criticism. He is also a skilled photographer, sculptor, and a committed media, language, and political activist.

Quinn returns time and time again to the main message of his scholarship. In 1998, he released the film, Atlantean 2: Navigatio, and in 2005, published a significantly expanded version of The Atlantean Irish. In the 2010s, he shopped around a third possible Atlantean film or series, but the funding never materialised. Beyond this cycle of text and images, Atlantean’s chief preoccupations and qualities resonated further afield. Its anti-imperialism and vivid depiction of culture and community as constantly shifting and evolving entities, crafted by many hands, are the undertow of his life and work.

This sui generis corpus amounts to a model for an independent and indigenous Irish cinema and television, divergent from a mainstream which is heavily commercialised and narrowcast. His influence ranges from his active participation in the ’70s and ’80s in the first wave of independent Irish cinema and the militant Irish-language pirate and community television movement, to the traces found in contemporary work of a myriad of filmmakers and artists today. Popular travel documentarian and writer Manchán Magan, who delves into the historical and global reverberations of Irish language and culture, has drawn from Atlantean openly and extensively, and Dónal Foreman’s metatextual west of Ireland fable, The Cry of Granuaile (2022), features a talismanic appearance from Quinn.

The Revolutionary’s Cultural Awakening

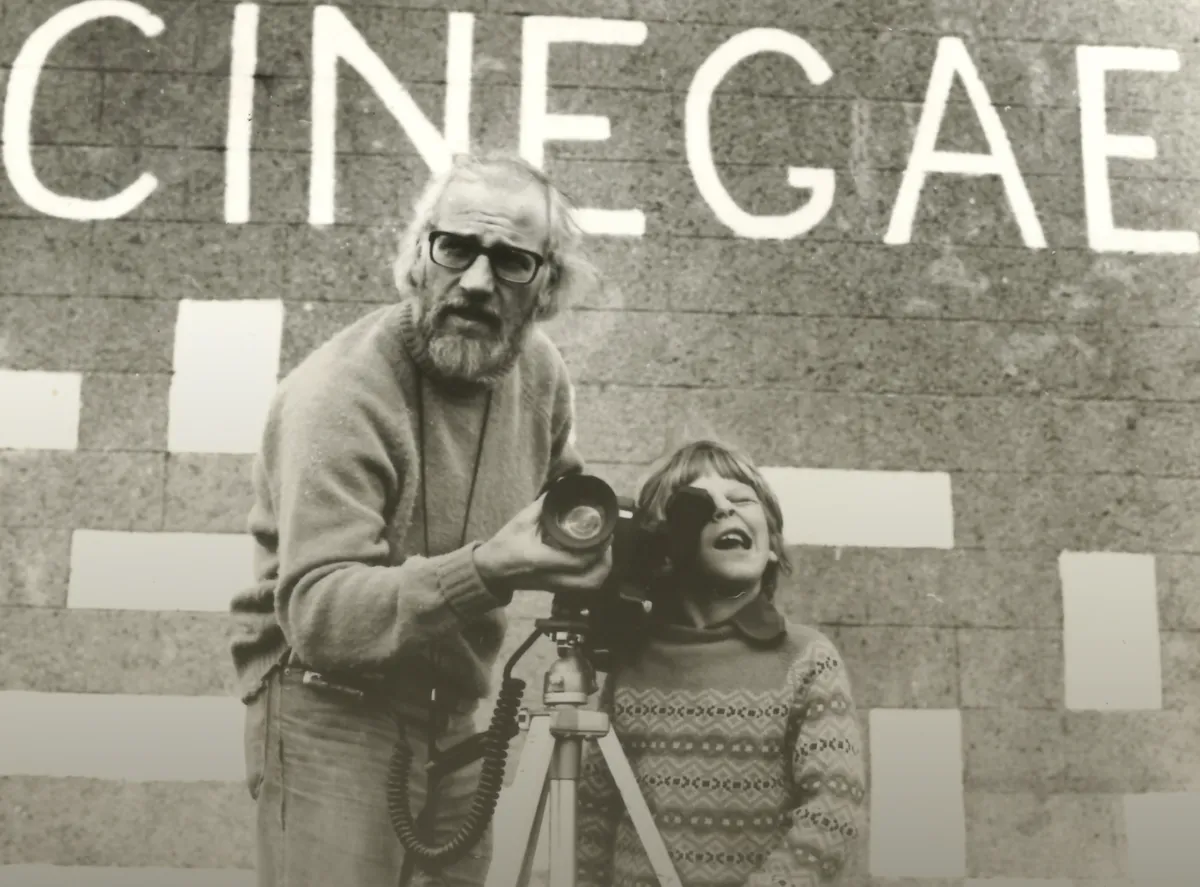

Bob Quinn shooting Poitín.

Born in 1935 to an “improving working class” family in Dublin, he got a job at RTÉ in 1961. Getting in at the ground floor of Ireland’s national public broadcaster—it was just barely a year old—within two years he went from trainee studio operator to producer and director, working on chat shows, news programs, and short documentaries.

Quinn has described his taste as a young man as not unlike many other young Irish urbanites of the 1950s and ’60s: preoccupied with classical music, jazz, and the movies. Neither he nor anyone in his family knew more than a few words of Irish, and traditional music was a foreign element which only very occasionally drifted through via radio. This would change with a drastic transformation in Quinn’s career, life, and outlook.

In 1968, Quinn, along with frequent collaborator Jack Dowling and fellow producer Lelia Doolan (like Quinn, a fundamental figure in independent Irish cinema and television for decades to come), very publicly left RTÉ. It was a protest of the channel’s increasing commercialization and censorship, as well as a critique of the station’s working structures. The trio elaborated on their reasons in a co-authored book, Sit Down and Be Counted (1969), a sprawling, spiky, and highly literate and impassioned account of Irish broadcasting and a manifesto for its future.

Quinn spent about a year in exile and reflection, working various odd jobs and traveling across Europe and as far as Iran. He would return to filmmaking in a new form when he and his family ended up, by chance more than intention, settling down in Connemara, a major part of the Gaeltacht—a collective name for those regions (spread throughout the country but mostly located on the west coast) where Irish is still spoken day-to-day.

The Quinns arrived in 1970, in the early days of Gluaiseacht Chearta Sibhialta na Gaeltachta (the Gaeltacht Civil Rights Movement), a grassroots civil rights campaign advocating not only for greater support for the Irish language, whose number of speakers was shrinking, but also economic improvement and political autonomy in the face of neglect by a state that revolves, economically and culturally, around Dublin.

Quinn immersed himself in his new home, becoming a fluent Irish speaker and ingratiating himself into the wider community and An Ghluaiseacht. His most prominent contribution was co-founding Cinegael with activist and journalist Seosamh Ó Cuaig and University College Galway lecturer Tony Chistofides, with ongoing support from his then wife Helen. Cinegael’s most well-known manifestation was as the production company behind the vast majority of Quinn’s films. It was also a community cinema, run out of the Quinn home, which they converted from an old knitting factory.

They showed popular titles like Dr. No (1962) and Enter the Dragon (1973) but also short films and video segments Quinn directed about Connemara, the Gaeltacht, and its people. In the documentary Cinegael Paradiso (2004), Quinn describes this aspect of Cinegael as a “closed-circuit television service.” Infused with the grassroots ethos of An Ghluaiseacht, it covered local figures and events, and included experimental reimaginings of established genres such as news, educational documentaries, and magazine shows. In the early to mid-1970s, when indigenous Irish film production mainly comprised a small output of short documentaries and TV was largely monopolized by the state but dominated by American and British advertising and programming, this was a unique and daring attempt at making moving images a truly communal and democratic medium.

The Atlantean Theory Unfolds

Atlantean is Quinn’s most well-known work and one of his most debated. Met in 1984 with a mixture of praise and ire, it was embraced by artists and scholars of many disciplines but also had its critics. Some of whom voiced skepticism towards several of Quinn’s ideas and findings, if not the series overall, while others found it entirely illegitimate, fueled in some cases by a conscious or unconscious racism. Regardless of whether one agrees with each hypothesis or not, Atlantean is vital as a work of moving images and decolonization.

The broad strokes of Quinn’s theory constitute a refutation of the conventional view of the origins of Gaelic culture—that the Irish people, along with its language and rich traditions of art and craft, descended from people dubbed “the Celts.” In conventional scholarship, these people were a collection of tribes who migrated west out of Eastern Europe during the Iron Age until they reached the Atlantic seaboard, making the present-day “Celtic” cultures of Ireland and Britain, along with Brittany and Galicia, remnants of a once pan-European civilization.

Quinn hypothesizes that the Irish identity wasn’t imported from Europe through conquest but instead fermented within Ireland while also being significantly shaped by cross-cultural pollination with the Iberian Peninsula and, most radically, North Africa through ancient trade links established across the open sea. For Quinn, this exchange, which continued through the Middle Ages up to the early Modern era, means that Ireland today was informed as much by contact with Africa, the Middle East, and Islam as by Europe and Christendom.

Atlantean.

For Quinn, this exchange, which continued through the Middle Ages up to the early Modern era, means that Ireland today was informed as much by contact with Africa, the Middle East, and Islam as by Europe and Christendom.

Quinn’s starting point was twofold. The first was his encounter with séan-nos singing, a form of Irish folk singing usually performed solo and unaccompanied, defined by its intricate, wandering melodies. This style, to Quinn’s ears and many others, sounds closer to Amazigh and Arabic singing than to Irish, English, and Scottish folk forms that form a significant chunk of western popular music’s bedrock. The other starting point was the sea itself, with western coastal regions like Connemara maintaining a much stronger boating culture, both quotidian and artisanal, than the rest of Ireland, from the prevalence of fisher folk to the region’s long, popular history of regattas or boating competitions. Through the latter, Quinn would eventually make the comparison between the sails of the Galway húicéir (hooker) and the Egyptian dhow.

From these two clues, Quinn constructs an elaborate travelogue in three parts, travelling between Ireland, Britain, Spain, Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, and other countries and covering thousands of years of history, art and movements. The first episode establishes the ideas of Atlantean and the beginning of Quinn’s quest, taking viewers to Morocco where he compares many similar elements in Irish culture and language with their counterparts in Arabic and Amazigh. The second expands on these connections, comparing many similar instances across different areas of culture, from textiles to language. And the finale takes religion as its main theme, investigating the influence of the Egyptian Coptic Church and Gnosticism on early Irish Christianity before it was fully brought in line with Rome’s dictates and dogmas.

Quinn takes a bricolage approach—a warp and weft of observational scenes with interviews with musicians, artists, historians, linguists, and archaeologists, along with details of many different objects of sculpture, textiles, architecture, and art. The most fundamental components of this patchwork filmic language are woven from the berth of his ideas: singing and the sea. The rhythm of these films is based on recurring motifs such as the tide and rolling waves along with scenes of people singing, whether in a pub in Connemara or a mosque in Egypt.

Using this material, he constructs dynamic, highly musical sequences. In Part One, an observational sequence of Moroccan women walking down a street is overlaid with the singing of Irish women, an everyday scene imbued with a deep sense of common experience, joined across thousands of miles through the traversal power of the cut. This sequence finds its expansion in Part Three, where a tightening side-by-side comparison of two singers, one Amazigh and the other from Connemara, reaches its crescendo in the turbulent cross-cutting between a boat journey and two separate scenes of bands from these two cultures playing at full tilt.

Aside from these remarkable individual montage-compositions, short scenes of song and sea are spread throughout all three parts like a network of lighthouses lining and linking the Atlantic coast. They gave the series its structure and rhythm while making Quinn’s ideas tangible to a level that words alone could never penetrate.

One of the most striking aspects of Atlantean is its narration. Though Quinn does appear in the films and is occasionally heard, he is not the predominant voice. Instead, it’s a concocted character—an imperious, upper-class Englishman voiced by Alan Stanford—who openly scoffs at and criticizes Quinn and his ideas, denigrating him as a foolish barbarian on a wild goose chase.

When asked about this odd creative choice of a fictitious and oppositional voice, rather than his own, Quinn replied,

| That was a very intentional device to elicit sympathy of the viewer because I knew this voice would antagonize them and if it was antagonistic towards my ideas, that would evoke sympathy from the viewer. The [supposed] superiority of the English accent to the Irish brogue has always irritated me, and so I used it in reverse. |

More than a structuring device or a pantomime villain, this phantom of colonial historiography also critiques the documentary form, sending up the voice of authority—often masculine and privileged—used in many historical and travel documentaries to steamroll complex sociopolitical histories and realities into bite-sized form. It’s an act of oversimplification or outright erasure to which colonized peoples are particularly prone. Quinn was deeply influenced in his early career by Antonio Gramsci’s views on the intellectual’s place in a revolutionary society as the proponent of new forms of thought in tune with the proletariat's new emerging class consciousness. This embodiment of the old order of hierarchy and division gives Atlantean dialectical thrust—a point against and around which Quinn, the intrepid organic intellectual, can draw a map of new possibilities.

More than its individual, myriad connections and propositions, Atlantean’s greatest achievement is its big picture: a spirited proposal to dislodge Ireland from racist and imperialist formulations of European civilization and the West.

What Comes After Revival?

Quinn, as a “blow-in” to western Ireland whose work is so deeply concerned with the region and its community’s survival, plays a complex part in the long lineage of political thinkers, philosophers, and artists who have traveled west on a mission to recover an Irishness unspoiled by the vicissitudes of colonialism, most notably during the Gaelic Revival of the late 19th century (a period of cultural renaissance which culminated in the War of Independence). Since large stretches of the west are unsuitable for the intensive growing of grain, it did not fit easily into Ireland’s role as Britain’s “breadbasket.” Its people were conquered and disenfranchised, but did not experience the same level of Anglicization. English and Scottish settlers arrived in lower numbers compared to the south, east, and most enduringly, the north.

Many of these interactions between West and East were marked by a paternalistic attitude, as epitomized by the poet and impresario W.B. Yeats’s advice to young playwright J.M. Synge, encouraging him to travel west, speak to people, and gather tales and idioms to “express a life that never found expression.” Yeats, a committed nationalist but also a member of the Anglo-Irish upper crust, believed in the supremacy of the written word. Millennia of rich oral, musical, and handmade culture represented to him not a void, certainly, but fertile, inchoate material to be given a more potent form when put down on the page by the new elite.

For Quinn, the Irish language and the west’s oral, musical, and craft traditions are already expression in their highest state, whether “discovered” by the likes of Yeats or Synge or not. More than its individual, myriad connections and propositions, Atlantean’s greatest achievement is its big picture: a spirited proposal to dislodge Ireland from racist and imperialist formulations of European civilization and the West, of which Yeats, despite his belief in revolution and his influence on figures like Edward W. Said, was a firm believer. As Édouard Glissant put it, these are not geographical regions but concerted political projects whose enlightenment gloss covered exclusion, exploitation, and domination. Quinn’s films encourage us to rethink such divisions’ very validity and to know them for what they are.

By the end of the 1970s and into the early days of the Atlantean project, the Cinegael cinema had closed under the threat of legal action, and so its incarnation as a cinema and a community television station concluded too. Quinn’s later work, while retaining this independent, communal focus and spirit, would largely be exhibited through more established means: film festivals, theatrical runs, or freelance production for government-funded TV stations like RTÉ and TG4. However, this rich experimentation in moving images as a communal form, co-authored by a community of people rather than imposed on them, is echoed in Atlantean’s egalitarian ethos and much of Quinn’s other work and practices to date.

The flexibility of Quinn’s worldview draws from his social background—less privileged but more mobile than Yeats’s—his deeply held belief in television’s social function, and his early career’s vicissitudes in moving images. The decolonial voyage of Atlantean represents a practice and vision starkly different from the mainstream of Irish film and television, then and now. In mimicry of the Irish state overall, which in the mid-20th century hitched itself to a new colonial master—namely American corporate and military power—the dominant view of what makes a successful or flourishing Irish film industry is as a barnacle on Hollywood’s hull.

The making and the message of Atlantean counter this supposedly unshakeable dogma by proposing that culture, whether it takes the shape of language, boats, music, or cinema, is constructed by humans and so can be reconstructed by humans—ideally under conditions true to the circumstances, ideas and aspirations of the many and not just for the profit of the few.

Editor’s note, August 22: This article has been corrected to more accurately reflect the dates, locations, and collaborators of Bob Quinn’s early life.