In 1992, the Tunisian filmmaker Férid Boughedir declared, “African cinema quotes itself. This is a sign that it now has a history.” A decade on from Caméra d’Afrique (1983), his documentary survey of the first 20 years of indigenous sub-Saharan African fiction cinema, Boughedir was asserting that, far from being just a theoretical concept, something known as African cinema—a set of films from the continent with shared political concerns, shared formal and aesthetic characteristics, films aware of and influenced by one another—actually exists.

Boughedir’s insight about quotation creating cinema history raises a crucial question for the Caribbean. Given its ineluctable echoes with the ancestral continent of the majority of its inhabitants, can the region also claim a cinema history? The recent restoration and recirculation of a significant number of nonfiction and docufiction films, formally and politically kindred works spanning several decades—including shorts of the Puerto Rican film unit in the 1950s, short films by Cuban directors Sara Gómez and Nicolás Guillén Landrián from the 1960s, and a series of feature- and medium-length films from other countries from the 1970s and ’80s—prompts a sharper focus: is there such a thing as a Caribbean documentary cinema history, and specifically, a history of liberation cinema?

The Caribbean’s unique colonial history—from Indigenous decimation and African enslavement by imperial Europe, as well as successive waves of migration from across the globe, to formal independence and mass diasporas in the Global North—resists conventional analysis. Any cartography of Caribbean documentary must reckon with this complexity. That is to say, the Caribbean’s persistent underdevelopment and subsequent lack of cohesion in its history of cinema production complicates any telling of that history—even for documentary, which requires fewer resources than fiction filmmaking.

It is a porous, ad hoc narrative of starts and stops, of gaps and archival incompleteness; a narrative of films made by individuals from within the region and also from without; of sui generis, collaborative endeavours made in transnational contexts. Yet a gossamer thread connects many of the disparate efforts to create a critical, political cinema. This thread reveals itself in different patterns—some films working within state structures, others in militant opposition, still others in grassroots pedagogy. What unites them is the adoption of cinema as a tool by Caribbean people in the ongoing struggle for authentic, fully realized liberation.

El Puente. Courtesy of Amilcar Tirado

State-Funded Beginnings and the Puerto Rican DIVEDCO

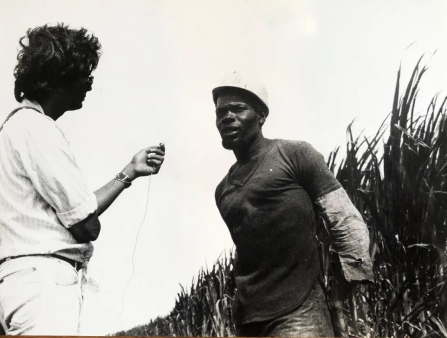

Caribbean people did not make the earliest films in the Caribbean, nor were those films made for them. These films consisted of short, initially silent newsreels by metropolitan agents such as John Grierson’s British agency, the Empire Marketing Board, documents that mischaracterized the people, society, and culture. The short Windmill in Barbados (dir. Basil Wright, 1933) reflects the occasionally liberal-humanist bent of this kind of filmmaking. A lyrical study of the cultivation of sugar cane and the nobility of the workers engaged in it, the film nevertheless lacks critical impulse, eliding the sugar industry’s historical reliance on slavery and the systemic poverty and racism of contemporary Barbadian society.

Around the middle of the century, emerging from the Second World War and on the path of self-determination, British Caribbean colonies such as Jamaica and Trinidad began to make the first noteworthy examples of indigenous Caribbean cinema. These shorts were typically official state productions from colonial film units. A lack of independent resources and opportunities for training meant that filmmakers, whatever their political proclivities, found themselves shoehorned into making didactic government propaganda that was little more than educational films. The title of a Jamaica Film Unit production, Farmer Brown Learns Good Dairying (dir. Martin Rennalls, 1951), is typical.

Across the Caribbean Sea in Puerto Rico, however, the artists of that island’s film unit, the Division of Community Education (DIVEDCO), were attempting to subvert the official government line in their work. Founded in the late 1940s by the administration of the first Indigenous governor under U.S. rule, Luis Muñoz Marín, and producing scores of films over the ensuing decades, DIVEDCO was part of the sweeping series of economic, social, and cultural reforms known as Operation Bootstrap. These reforms were meant to (1) create large-scale industrialization and urbanization and (2) induce mass migration to Puerto Rico’s cities and the U.S. mainland, as the island went from colonial status to commonwealth (colonization under a different guise). Led by the Ukrainian émigré Jack Delano, the directors in DIVEDCO had other ideas.

Broadly nationalist and socialist in their outlook, the filmmakers sought to push back against the state’s mandate by articulating a different vision, radical in its own way, about what development could look like. Made in and with rural communities, with the peasantry as their primary audience, these accomplished, short documentaries and neorealist fictions—influenced by Soviet montage and Robert Flaherty—privileged communal organizing and action, with an emphasis on the people’s sovereignty over their land and their right to decide their own affairs. Films such as El puente (The Bridge, dir. Amilcar Tirado, 1951), detailing a village coming together in self-reliance to build essential civil infrastructure, and Ignacio (dir. Ángel F. Rivera, 1956), in which a poor farmer takes a stand against authoritarian local village power, reflect the utopian impulse of Puerto Rico’s first filmmakers.

In the end, the government’s vision won the day, a vision that ultimately failed and led to the economic stagnation in Puerto Rico today. DIVEDCO finished its most important work by the late 1960s, and the film unit was shuttered in the ’80s. Yet the influence of the unit, and the spirit of solidarity that animated it, reached beyond the island. Cuban filmmakers, first working independently, would echo many of DIVEDCO’s innovations in their work, from the use of non-actors, a focus on rural communities, and the neorealist aesthetic that privileged collective action over individual heroism.

The Caribbean’s persistent underdevelopment and subsequent lack of cohesion in its history of cinema production complicates any telling of that history—even for documentary, which requires fewer resources than fiction filmmaking.

Cuba and the Documentary Cinema of the Revolution

In 1955, the Cuban filmmakers Julio García Espinosa and Tomás Gutiérrez Alea made a short film titled El mégano. Set in a swamp among a community of impoverished charcoal burners, this docufictional work, with workers enacting scenes from their hardscrabble daily lives, echoed the work of the Puerto Rican film unit on a formal level. The Cubans, however, working independently, had a more politically radical intention: to use cinema as a weapon in the fight against the corrupt dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. At one point in El mégano (which Batista would ban), an indignant worker cries out, “Things can’t go on like this, boys!” Four years later, the Fidel Castro–led revolution would triumph, bringing a new order, and a new cinema, to Cuba.

Cuban revolutionary cinema is acclaimed primarily for the fiction features produced by Gutiérrez Alea and Espinosa, among others. Yet the documentary work of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) not only played a propagandistic role in advancing the social, economic, and other domestic aims of the regime, but also reflected the greater, growing struggle for liberation by oppressed and colonized peoples elsewhere. Indeed, documentary, with its potential to educate a society no less intellectually impoverished as it was materially underdeveloped, was the initial focus of ICAIC.

Santiago Álvarez, one of the key figures of Latin American Third Cinema, was at the forefront of Cuba’s documentary cinema. Acclaimed for developing a style of dynamic montage, typically using appropriated images while forgoing didactic voiceover, Álvarez led production of ICAIC’s weekly Noticiero ICAIC Latinomericano newsreels. His agitprop style was most notably expressed in Now! (1965), set to the titular Lena Horne song, a furious denunciation of U.S. racism against African Americans, and the equally incendiary LBJ (1968), which extended this satirical critique to U.S. government involvement in Vietnam.

While the Cuban state approved of this critique of its capitalist neighbour to the north, it nevertheless expected Cuban filmmakers to analyze the revolution itself with circumspection (“Within the revolution, everything; against the revolution, nothing,” in Castro’s famous dictum). This extended to the subject of race, in what was now, officially, a colorblind society, as well as gender. This is the context within which the short documentary oeuvres of the Afro-Cuban filmmakers Sara Gómez and Nicolás Guillén Landrián, long neglected and in recent years the recipients of overdue reappraisal, should be seen. (In just the last year, Documentary covered retrospectives of Gómez and Guillén Landrián restorations at IDFA and Il Cinema Ritrovato.)

Both filmmakers knew that despite official pronouncements, Afro-Cubans remained economically and socially marginalized. Unable to critique the revolution head on, they employed various creative strategies to consider race and gender indirectly.

In Mi aporte (My Contribution, 1969), Gómez employs interviews and group discussion to allow Cuban workers, women and men, to reveal the challenges women continue to face in a society still rife with machismo. Guillén Landrián’s Coffea arábiga (Arabica Coffee, 1968) has a more formally radical approach, reconfiguring a didactic documentary on agricultural production into an associative essay that suggests slavery’s horrors persist.

Whatever else can be said about the revolution and its cinema, the example these Cuban filmmakers provided would be a beacon to liberation movements elsewhere, including other parts of the Caribbean. There, a liberatory documentary cinema would soon be made in earnest.

Haiti: The Way to Freedom. Courtesy of Arnold Antonin

Women of Suriname. Courtesy of Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms & LOSON

The Terror and the Time. Courtesy of the Victor Jara Collective

A Caribbean Cinema for Liberation

While the revolution’s ongoing attempts to transform Cuban society still held hope there, the picture looked quite different across much of the rest of the Caribbean. Ongoing systemic poverty and inequality, social disaffection, a growing commercial and cultural dependence on the United States, and corrupt and repressive political regimes—no longer colonial, though only nominally democratic—were the order of the day. In the wake of the political and social upheaval that ricocheted around the globe in the late 1960s, including the rise of Black Power, leftist agitation and organization—undergirded by Marxist discourse and the theories on race and colonialism of Martinican thinkers Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire, among others—welled up across the region.

Whereas DIVEDCO in Puerto Rico worked within state structures to subvert official mandates, and Cuban cinema innovated to serve revolutionary aims, the films emerging across the Caribbean in the 1970s took a different approach. Although arriving late to the Third Cinema movement, filmmakers nevertheless began picking up 16mm cameras to turn out a new kind of Caribbean documentary cinema: a radical, even militant cinema.

One of the salient elements of this cinema was that, unlike what often obtained within Third Cinema movements in Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Arab world, movements such as Brazil’s Cinema Novo, every film made in the Caribbean was a movement unto itself. In most cases, whether intentionally or not, the films—a mix of features and mid-length works—were one-off productions, irruptions that accompanied and were sometimes directly born out of activist struggles for social, economic, and political reform in separate countries.

While the films were all made within separate and essentially unconnected contexts of production, one striking unifying element is the great sense of collectivist solidarity that pervades them. Even when credited to named individuals (as opposed to collectives) as the directors, these documentaries, not unlike the shorts of the Puerto Rican film unit, tend to have a genuine feeling of communal authorship—of being shaped by many hands in a common cause.

Ayiti, men chimin libete (Haiti: The Way to Freedom, dir. Arnold Antonin, 1975) was one of the first films of this new liberationist Caribbean cinema. Announcing itself as a work by the “revolutionary organization” 18 Me—Demokrasi Nouvel (May 18th—New Democracy), and regarded as the first Haitian feature, Ayiti, men chimin libete is a guerrilla strike against the brutal Duvalier père-et-fils political regime. It employs an Álvarez-ian, rapid-fire synthesis of original footage, archival images, and polemical narration, delivering a master class in the historical and ongoing depredations against the Haitian people by its ruling elite and their external allies.

The film begins with the performance of a Haitian folk song; in other liberation films to follow, Indigenous folk tunes and protest songs are similarly heard soundtracking the documentation of the struggle. At the end of Ayiti, men chimin libete, some text appears that hints at how the film was financed, underlines its aims, identifies its target audiences and what it is meant to make them do, and even suggests how to show the film. It is worth quoting in full:

Many thanks to all our foreign friends without whose aid this film could not have been made. This film may be used in the anti-Duvalier struggle by anyone, with due credit to the makers. This film sets out to expose to Haitians what happens and what has happened in their country in order to change things. This is an appeal to all that they unite to crush the criminal and depraved Duvalier dynasty. Finally, it tries to inform other peoples about the continuing struggle of the Haitian people against local and foreign exploitation.

The measured yet urgent tone is in keeping with all of Ayiti, men chimin libete. More than this, the unapologetic declaration of the film’s purpose as a work of both pedagogy and activation, and the spirit of transnational solidarity that pervades the whole endeavour, echoes across the films that would follow. Further, the suggestion that “this film may be used in the anti-Duvalier struggle by anyone” is instructive of the exhibition circuits these films traveled. Rather than commercial cinemas—which, where they existed in the Caribbean, showed (and still mostly show) only metropolitan studio films, and before the proper advent of festivals geared toward political cinema—these films found their audiences in informal, community settings in the region and across the diaspora.

Every film made in the Caribbean was a movement unto itself. In most cases, whether intentionally or not, the films—a mix of features and mid-length works—were one-off productions, irruptions that accompanied and were sometimes directly born out of activist struggles for social, economic, and political reform in separate countries.

A concern specifically for the rights of working people and a desire to expose the exploitation of their labor, particularly of sugar cane workers, repeats across several of the films. Immersed in the sugar fields of the French département of Guadeloupe—subjects’ testimonies are gathered while they reap the canes—and directed by Gabriel Glissant, a Martinican actor based in metropolitan France known for his work with director and producer Med Hondo, La machette et le marteau (The Machete and the Hammer, 1975) is a forensic look at the economic system of the original-sin commercial crop that keeps the workers in an impoverishing cycle of dependency on the comprador bourgeoisie. Broadening out to encompass the burgeoning economic-nationalist protest movement and its intersection with the agitation of an awakened intellectual class, the film ambitiously makes the case for an island in the middle of liberatory upheaval. Frenchman Jérôme Kanapa’s Toutes les Joséphine ne sont pas impératrices (Not All Josephines Are Empresses, 1976), made in Martinique the following year, similarly focuses on agricultural labor, refracting the workers’ struggle through a female banana plantation laborer.

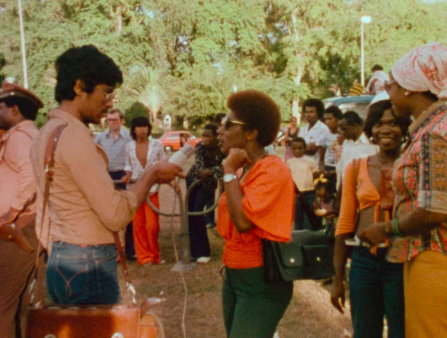

A different approach to gendered labor appeared in Oema foe Sranan (Women of Suriname, dir. At van Praag, 1978), which blended testimony, fictionalized reenactment, and direct polemics in its examination of the status of women across the newly independent Surinamese society and its diaspora in the Netherlands. A collaboration between the National Organization of Surinamese Organizations in the Netherlands (LOSON) and Cineclub Freedom Films, a radical Dutch filmmaking collective, and a far cry from the model of colonialist filmmaking of Britain’s Empire Marketing Board, Oema foe Sranan beautifully reflects a transnational mode of working between not only a Caribbean nation and its diaspora but also activists from a former colony and those of its former colonizer making common cause.

If Cuban filmmakers faced constraints working within revolutionary state structures, these filmmakers elsewhere confronted funding gatekeepers and political repression that prevented films from reaching their intended scope. Restored recently after being missing for many years, the mid-length Oema foe Sranan was a compromise: the collaborators originally planned a trilogy of shorts followed by a feature, but Dutch funding bodies denied their requests, which the filmmakers considered a form of censorship. Similarly, the Victor Jara Collective’s 1979 feature documentary The Terror and the Time (dir. Rupert Roopnaraine), out of Suriname’s neighbor Guyana, was meant to be the first of three films about that country’s exploitative colonial history and its ongoing impoverishment. Born from a Marxist study group at Cornell University, the Collective brought together activism and academia to produce a precise synthesis of historical-political-economic analysis, direct testimony, and poetic symbology. But political repression within Guyana put paid to the idea of a series of films. The Terror and the Time remains an exemplary work of liberation cinema.

While the films were all made within separate and essentially unconnected contexts of production, one striking unifying element is the great sense of collectivist solidarity that pervades them.

Grassroots and Subaltern Last Liberation Films

As the 1980s dawned, two decades on from the triumph of the revolution in Cuba, another leftist revolution prevailed in the Caribbean, in Grenada. Maurice Bishop’s New Jewel Movement, having overthrown the violently corrupt dictatorship of independence leader Eric Gairy, set about implementing Cuba-backed socialism on the island. The first majority-Black socialist and English-language revolution in the Americas, Grenada attracted a lot of attention, both welcome and unwanted, from various U.S. factions. In the welcome camp was John Douglas—he had directed, with Robert Kramer, Milestones, the epic 1975 survey of the post-Vietnam counterculture movement in the U.S.—who, along with Carmen Ashhurst and Samori Marksman, came to Grenada to document the new government’s successes.

Grenada: The Future Coming Towards Us (1983), with its accumulation of newsreel-style episodes of triumphs in literacy, housing, agriculture, and so on, was meant to be propaganda for a revolution triumphant, rather than, as with most of the rest of the liberation films that came out of the region beyond Cuba, propaganda for a revolution still being made. But the film became something else entirely. Internecine fighting within the Grenada government, the assassination of Bishop along with seven of his colleagues, and a U.S.-led military invasion turned the completed film into a memorial for a utopian intervention undone.

As U.S. neoliberalism began reshaping the region’s political economy, two other remarkable, also recently restored films of liberationist intent emerged, testimony that the subaltern struggle continued on the ground.

Made a decade after Ayiti, men chimin libete, and firmly taking up the torch lit by that film, Canne amère (Bitter Cane, dirs. Ben Dupuy and Kim Ives, 1983) was another broadside against Haiti’s Duvalier dictatorship and its ongoing exploitation of the Haitian people in concert with multinational interests. Bitter Cane telescopes the historical contextualization set out at length in Ayiti, men chimin libete, taking advantage of remarkable access to devote much of its runtime to testimonies from agricultural laborers and factory workers, as well as self-indicting middle-tier local landowners and foreign businesspeople.

Bitter Cane was shot both clandestinely and under false pretenses, and originally credited to a single fictional director to protect the Haitians who worked on it, many of whom were affiliated with the organization Mouvement Haïtien de Libération. Crucially, given the U.S. business interests embedded in Haiti, the film contains sequences set in the U.S., which register the growing undocumented migration out of Haiti and the protest movement within the diaspora against the Duvalier government. Given recent electoral debates in the U.S., one sequence, set in a West Virginia blue-collar community suffering the fallout of industry’s moving to Haiti to take advantage of more exploitable labor and conditions, is particularly striking for its prescience.

Bitter Cane. Courtesy of Kim Ives

Not long after Bitter Cane appeared, Jean-Claude Duvalier was deposed, setting Haiti on a long, daunting road to democracy. If one were to consider, however, a functioning—if imperfectly working—democracy, arguably nowhere in the Caribbean did the ideological battle between competing visions for governance and development manifest itself more clearly than in Jamaica. During the 1970s, a leftist government had run it; the 1980s brought a right-leaning one, the two sides infamously playing out an often-violent proxy war between opposed Cold War world powers. The great mass of Jamaicans remained on the island’s economic margins, and it was within this context that the documentary Sweet Sugar Rage (dirs. Honor Ford-Smith and Harclyde Walcott) appeared in 1985.

Looking at Sweet Sugar Rage, it is possible to trace a lineage back through films like Oema foe Sranan, with its dramatized stagings of the real-life situations of workers, and Mi aporte, with its tableaux of workers in fervent discussion about their problems and how they might be resolved. Yet Sweet Sugar Rage, indicative of a larger reality concerning filmmaking in the Anglophone Caribbean, is better seen as the unique cinematic intervention that its context of production suggests. Made by first-time directors who would never make another film, it emerged from the work of the feminist collective Sistren, a grassroots consciousness-raising theatre collective focused on the experiences of working women.

As with Sistren’s stage plays, Sweet Sugar Rage represents a third model of liberation practice, neither state-funded subversion nor guerilla agitprop, but grassroots pedagogy. Hewing closer to the possibilities of art delineated by the Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire in his Pedagogy of the Dispossessed than postcolonial theory, and made in a manner not unlike the films of DIVEDCO in Puerto Rico, it exemplifies the vernacular democratization of art making that Cuban filmmaker Julio García Espinosa called for in his 1969 manifesto, “For an Imperfect Cinema.”

In the polyvocal Sweet Sugar Rage, testimonies are gathered of the problems women face regarding poor working conditions and low wages from women working in the sugar cane fields, before being brought to the theater and collectively dramatized in an attempt to find solutions to the problems. The camera is immersed and alive. Excitement mounts as ideas are presented, critiqued, and refined. The film ends, thrillingly, in media res; possibilities for change remaining open, even infinite. Liberation is an ongoing process.

Sweet Sugar Rage. Courtesy of Third World Newsreel

What Happened? And What Happens Now?

Films find the forms their times demand. The revolutionary fervor that fed Third Cinema across the Global South could not last indefinitely, no matter how various liberation movements resolved (or perhaps more precisely, failed to resolve) themselves. It was no different for filmmakers working in the Caribbean or Caribbean activist and liberation movements. As social and political winds shifted, so did filmmaking impulses. Where films continued to be made, the collectivist model was replaced with one that resembled an industrial model.

More prosaically, the money dried up. In Cuba, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Cuban economy’s “Special Period” resulted in ICAIC production practically coming to a halt, from double-digit numbers of features at its peak to just one or two a year.

And yet, a look back from this vantage point reveals—however imperfectly, however indirectly—an attempt over decades by artists and activists to make a Caribbean liberation cinema and thus create a Caribbean cinema history; one where films, however incompletely, do quote each other. The isolation imposed by history, underdevelopment, repression, and limited circulation means this quotation remains partial, a gossamer thread visible only now through restoration and recirculation. Liberation cinema created a history, but it is one that has to be recovered.

The material reality of the Caribbean is what it is. The current demand for slavery reparations, as much as it is a call to acknowledge and recompense brutal historical crimes committed against the ancestors of the region’s people, is a profound testament to this. A related reality, not as clearly articulated, also persists concerning the less tangible questions of Caribbean people’s identity and visibility. In recent years, a new nonfiction cinema has been emerging that attempts to articulate, however inchoately, these various, repeating concerns. Unlike the earlier liberation films, which were made disparately yet nonetheless indirectly as part of a broader global movement of liberation cinema, this new cinema lacks commonalities by its very formal nature, which pushes back against any obvious categorizations.

It is a cinema of ongoing resistance without revolution’s organizing principles. Much of this new cinema, though often cognizant of liberation cinema and the theories that animated it, is marked by political ambivalence, even an understandable pessimism, and has a poetics all its own. These films are informed by newer generations of Caribbean and diaspora thinkers: Stuart Hall with his theories of multicultural identity, Sylvia Wynter and her concerns with historical responsibility, Édouard Glissant with the right to opacity. Made by students of the art form, this cinema draws too from other spheres of documentary filmmaking, particularly films that raise ethical anxieties about presuming to speak on behalf of less privileged others.

The following examples are illustrative. Opacity is at the heart of Ouvertures (dir. The Living and the Dead Ensemble, 2020), a collaboration between Haitian and European artists and filmmakers that notably refuses a direct engagement with the country’s precarious sociopolitical reality. Instead, it uses rehearsals for a production of Glissant’s 1961 play Monsieur Toussaint, about Haiti’s revolutionary leader, as the point of departure for an experimental exercise in historical investigation, shared authorship, and collective filmmaking practice.

In recent years, a new nonfiction cinema has been emerging that attempts to articulate, however inchoately, these various, repeating concerns. Unlike the earlier liberation films, which were made disparately yet nonetheless indirectly as part of a broader global movement of liberation cinema, this new cinema lacks commonalities by its very formal nature.

The Haitian literary movement of Spiralism, with its attractions of narrative chaos, informs Malaury Eloi-Paisley’s L’homme-vertige: Tales of a City (2024), a poetic portrait of wanderers on the margins of Pointe-à-Pitre, the filmmaker’s decaying hometown in Guadeloupe (still a French département). In an indirect gesture toward La machette et le marteau, Eloi-Paisley registers her island’s independence movement, the People’s Union for the Liberation of Guadeloupe, the successor to Groupe d’organisation nationale de la Guadeloupe, the organization documented in La machette et le marteau.

Down south in Suriname, in a model of working that inspiringly echoes the making of Oema foe Sranan, the theater artist Tolin Alexander has collaborated with Dutch filmmakers Lonnie van Brummelen and Siebren de Haan on two features, De Sitonu a Weti (Stones Have Laws, 2019) and Monikondee (Money Land, 2025). Hybrid, self-reflexive works, these films center performance and ritual in their exploration of the creeping erasure of Maroon and Indigenous communities by neoliberal forces.

Most recent to emerge is the Cuban film To the West, in Zapata (2025). Directed by David Bim, who teaches at the country’s quasi-autonomous Escuela Internacional de Cine y Televisión (EICTV), which remarkably continues to regularly turn out films where ICAIC does not, To the West is an intimate observational portrait of a family struggling to survive in the very swamps of Espinosa and Gutiérrez Alea’s El mégano. While the workers in El mégano desire freedom from their misery, the family in To the West is resigned to their lot. Love is the only real currency in a film that has a quality of almost Sisyphean myth to it, while on the radio and TV, state propaganda proclaims a revolution bruised but battling.

The production and exhibition contexts of the new Caribbean documentary cinema have also fundamentally changed from the earlier era of liberation cinema. Whereas liberation films circulated through internationalist collaborations and communal environments, contemporary Caribbean documentary navigates film festival circuits, with their globalized hierarchies and gatekeeping. Films made in transnational class struggle have been replaced by ones made through international co-productions dependent on European funding bodies. The support of the “foreign friends” (as opposed to today’s foreign funders) who helped in the making of Ayiti, men chimin libete, the salutary solidarity that underpinned the production of Oema foe Sranan, and the communal, nonhierarchical ways in which audiences were able to see these films are modes of funding and production and exhibition that should be revisited.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Winter 2026 issue.