Dreaming to Change the World: The Victor Jara Collective and the Legacy of Third Cinema

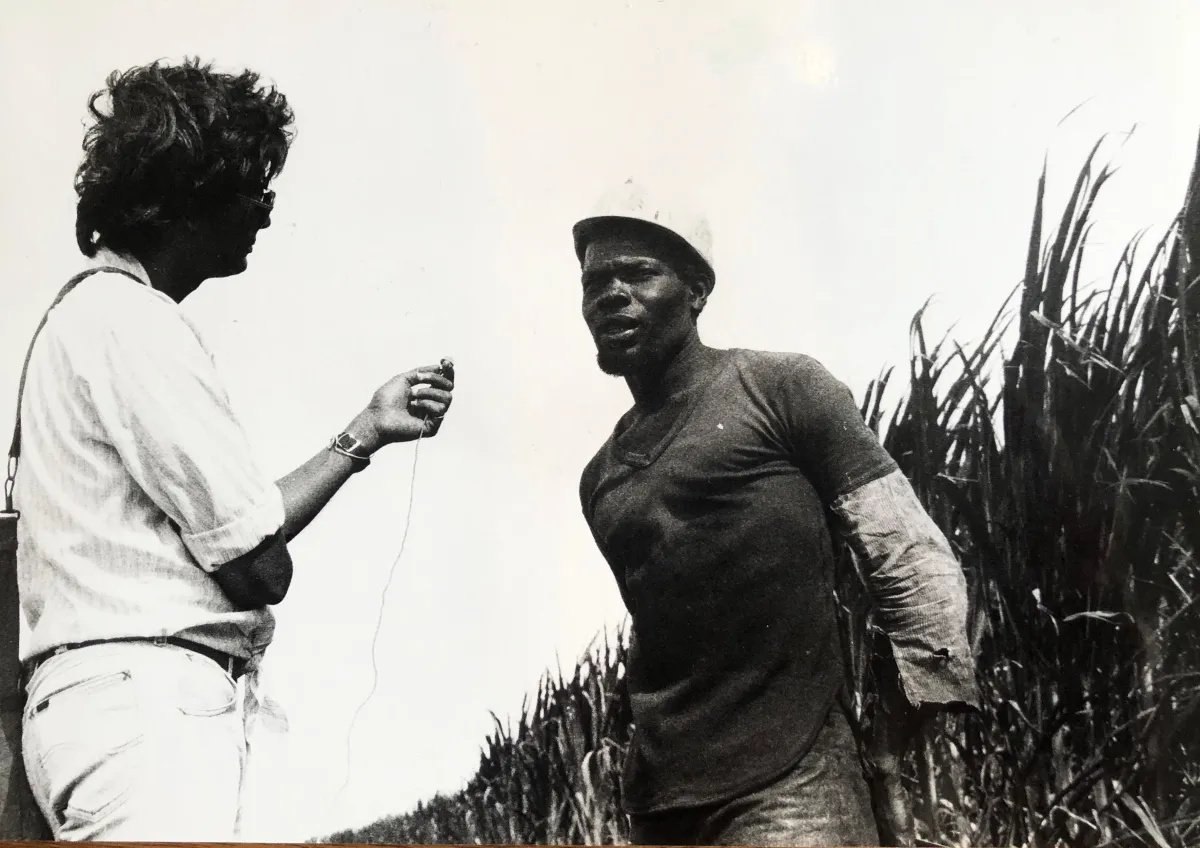

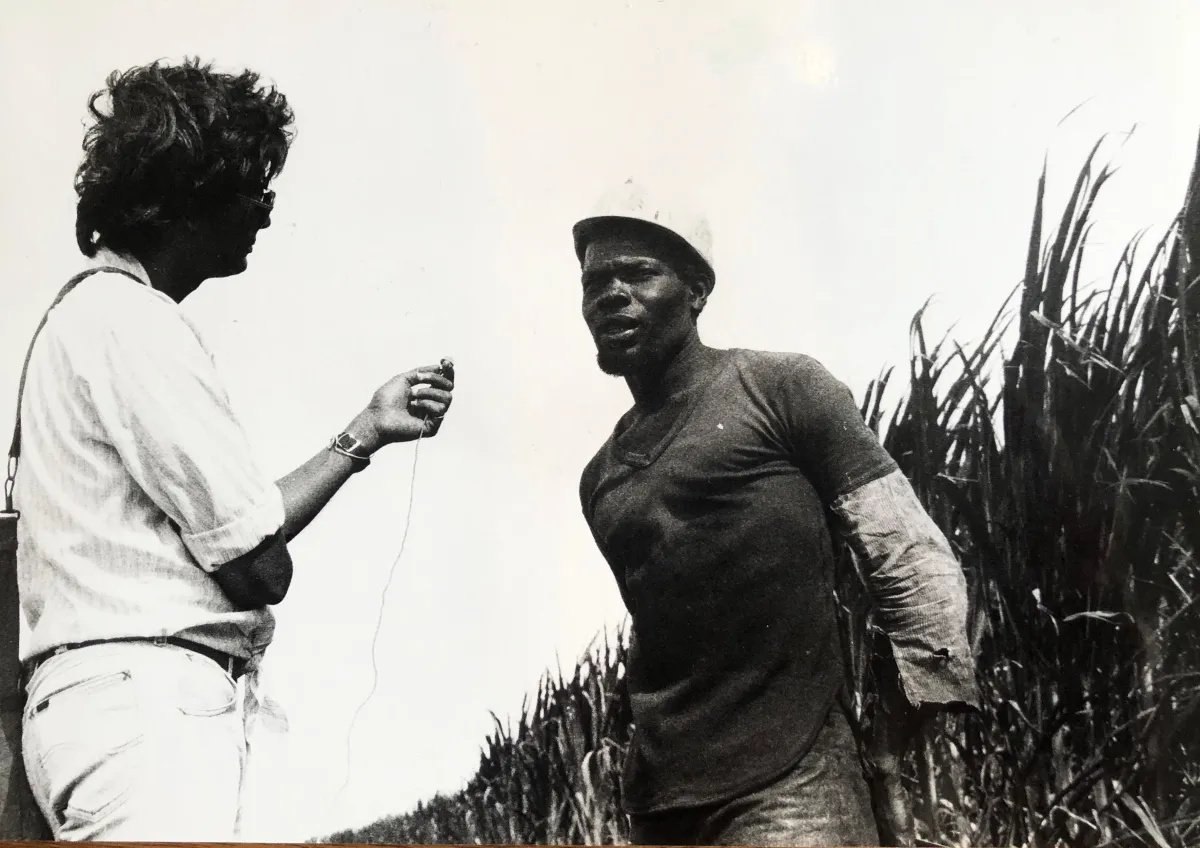

Rupert Roopnaraine conducts an interview for The Terror and the Time. Courtesy of the Victor Jara Collective

Imagine the hallways of Cornell University, a quiet, comfortable campus in upstate New York, in the mid-1970s. Now imagine, in one of the Ivy League rooms, a Marxist reading group that brings together students and professors from different generations, ethnicities, and countries. They are united by an urgency to make revolutionary art and contribute to the dismantling of imperialist capitalism. This is the origin story of the Victor Jara Collective, a coalition of artists and activists named after the revolutionary Chilean musician assassinated during the Pinochet regime.

Guyanese writer Rupert Roopnaraine was a sort of mentor for the other members of the collective. In 1976, he resigned from his very comfortable position as a professor at the Department of Comparative Literature at Cornell, teamed up with Ray Kril, Susumu Tokunow, and Lewanne Jones, and went to Guyana to make The Terror and the Time (1978), one of the most beautifully political—and politically beautiful—films of the last century. It was intended to be a three-part film on the struggles of the Guyanese working class and their repression by imperialist forces and the local bourgeoisie. Or, as Jones would put it in program notes, they went to Guyana “to make film, forge cultural alliances, and activate revolution.”1

For a few months between 1976 and 1977, the Victor Jara Collective collected archival material, recorded interviews and poetry readings, gathered sounds and images of workers’ struggles in the Caribbean country, and then came back to the editing facilities of Third World Newsreel in New York. The completed film is a masterpiece in which counterinformation and lyric poetry are not opposed, but rather contaminate each other—where rapid-fire montages of popular revolutions all around the then-called Third World and slow-motion depictions of Guyanese faces and landscapes harmoniously coexist.

Decades after its release, The Terror and the Time has resurfaced in recent years, including in October 2023 at the Valdivia International Film Festival in Chile, the home of Victor Jara. That’s where I had the chance to watch a well-preserved 16mm copy in the presence of Lewanne Jones, a member of the Collective who is now responsible for taking care of its legacy. According to Jones, the film was an internationalist endeavor from the beginning, but it was nonetheless dreamed, prepared, composed, finished, and distributed “in the belly of the beast,” the U.S., where the film’s current obscurity hides its true radicality. In Chile, all the screenings were packed. The post-screening conversations were intense and continued in the streets of Valdivia. Many festivalgoers considered The Terror and the Time to be the highlight of the festival—its struggle was urgent both in 1978 and now. We must also reconsider the film within the legacy of Third Cinema.

The Terror and the Time’s very first seconds start with flames emerging from a black screen to the drumming and singing of the Guyanese group Yoruba Singers. The beginning reminds us of the prologue of The Hour of the Furnaces (1968), Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas’s Third Cinema classic that became an ineludible reference for filmmakers all around the Third World during the ’70s, including the Victor Jara Collective. After the opening of pure sonic and visual energy, we see a well-known quotation by Frantz Fanon, which is also cited in Aloysio Raulino’s O Tigre e a Gazela (The Tiger and the Gazelle), a Brazilian film also released in 1978. But in The Terror and the Time, Fanon’s text is decisively fragmented. At first, only three words are shown. It’s a declaration of intent by not only the choice of words but also the way they appear onscreen:

The breaking of the original quotation transgresses the regular reading and creates a new one, demanding and engaging. Viewers have to work, to read against the grain, to contravene their expectations. Contrary to so many militant films, we are treated not as students enlightened at a movie theater converted into a classroom, but from the very beginning, as active participants in a collective process.

Roopnaraine’s idea of what a revolutionary film should be was a very particular one deeply connected with his vision of education. In an interview published in Guyana in 1978, Roopnaraine explains why they rejected using a voice-of-god narrator, despite its being a very common device in political documentaries:

| Part of what we reject when we reject the device of the objective narrator who explains and clarifies everything is precisely this master/slave notion of pedagogy. Instead of abolishing the freedom of the spectator, we have chosen to emphasize that freedom, to assert it at every level. Consequently, we have organized the film in such a way as to insist, as a prerequisite for understanding and action, on the active participation of the viewer in the production. The film, considered now as a process whose completion is achieved only in the act of consumption, relies on the viewer to perceive connections and relations. It invites practice, not acquiescence and passivity. The imposition of a narrator would have violated this principle. |

Instead of using a narrator, The Terror and the Time alternates between—and sometimes superimposes—essayism and poetry, counterinformation and lyricism. The deconstruction of Guyanese recent historiography to retell it from the point of view of the working-class movements coexists with a transfiguration, as opposed to an illustration, of the Poems of Resistance by Martin Carter. Each poem, read by the poet himself, gives way to a sequence in which the images blend between document and allegory, between realism and surrealism. In the first poem-sequence (“Cartman of Dayclean”), the flame we saw at the beginning returns as a lamp in a cart, while the driver slowly crosses rural landscapes during the night to get to the urban market by dawn. His journey is portrayed in carefully crafted shots, at a slow and delicate pace, of the cartman and the landscapes. In those sequences, the film is constantly stretching between documenting the precarious reality of workers in Guyana and composing highly elaborated visual and sonic allegories, which borrow their strength from the imagery already present in the verses and multiply it in unsuspected directions. The relations between the literary and the cinematic materials are never predictable. In a political film, the clarity of ideas is as important as the consistency of darkness.

Carter was a model for the film, not only because his verses counter the dominance of a more traditional narrator, replacing limpidity for evocation, explanation for immersion, but because his attitude toward art and politics was also symbolically important for the Victor Jara Collective. Carter was a popular, engaged artist and an intellectual committed to the struggles of Guyanese working people.

What we now know as The Terror and the Time is only the first part of the original project, centered on the historical facts of 1953. That year, after decades of struggle, the Guyanese workers’ People’s Progressive Party (PPP) won the majority of Parliament chairs in the first universal suffrage elections in the country, tried to keep a progressive government for four months, and then was taken out of power by a British military invasion. Carter wrote most of Poems of Resistance during that same year, in which he was persecuted and imprisoned by the illegitimate government. Following the repression, Guyana would remain a colony until 1966.

Inspired by the tripartite structure of The Hour of the Furnaces, the original intent was to make two more features, but history got in the way. In 1977, the PPP was again in power but far away from its roots. The party’s government, led by Forbes Burnham, initially supported the project by providing film stock, equipment, processing laboratories, and access to the archives of the Guyanese Film Center. But after watching a preview, they asked the Collective to remove the interviews with Cheddi Jagan and Eusi Kwayana, former members of the PPP who were now in the opposition. Tellingly, Burnham had refused to be interviewed for the film. The terror of British colonialism in 1953 was now the terror of censorship and media control by a nominally progressive government, but a repressive one in reality. Refusing to do what the government wanted, some members of the Collective returned to the U.S., smuggling the film cans in a cricket player’s unsupervised luggage, and continued the work at Third World Newsreel in exchange for distribution rights. To be able to finish at least the first part, they organized screenings and events where the work-in-progress was shown and raised money for survival and to continue editing.

In The Terror and the Times, the historical context of 1953 comes in an intense collage of archival material mingled with imagery generated in 1976/1977: old still photographs, fragments of films (taken from colonial British and imperialist U.S. newsreels), advertising, and newspaper clippings coexist with the Victor Jara Collective’s own contemporaneous footage. The images intersperse past and present because the conditions in 1977 were not that different from 1953. Instead of a boring, expositive analysis, intense reframing, juxtapositions, and dynamic recombinations of various sources keep everything in perpetual motion. Suddenly, a still image begins to tremble. Another one rotates. Throughout the sequence, joyful melodies bring irony and dissonance to the facts.

The voice of Cheddi Jagan, who takes on the task of a historian in the film, is not a singular sovereign but one element, among others. Anticommunist hysteria comes through a series of movie posters. A rapid collage of images of white women (including a Miss British Guyana) contrasts with slow, beautiful portraits of working people, mostly of African or Indian descent. The film embraces what Cuban filmmaker Santiago Álvarez called documentalurgia (“documentalurgy”) to define his composing methods in films such as Now (1965), LBJ (1968), and 79 Springs (1969); it doesn’t matter if the basic material is a still photograph, a shot from a colonial newsreel, a page from an ideological newspaper, or even a scene from a Hollywood fiction feature. All that matters is the act of appropriation, the particular use of these heterogeneous materials: the dramatic effects of combining documents, and the new emotions and meanings generated by intense cinematic procedures.

In intense dialogue with the Latin American militant film tradition, the Victor Jara Collective shares with filmmakers like Santiago Álvarez, Mario Handler, Carlos Álvarez, Octavio Getino, and Fernando Solanas the belief that revolutionary art should use cinema as a weapon, but that doing so does not mean trying to reduce it to a simple vehicle for ideas fabricated somewhere else, thereby underestimating its powers. To use cinema as a tool in a revolutionary struggle means exploring its potential to the fullest, embracing its visual and sonic possibilities and its poetic drive in a formally radical way. Solanas and Getino were well aware of that, as in their manifesto “Towards a Third Cinema,” published in 1969:

| The effectiveness of the best films of militant cinema show that social layers considered backward are able to capture the exact meaning of an association of images, an effect of staging, and any linguistic experimentation placed within the context of a given idea. Furthermore, revolutionary cinema is not fundamentally one which illustrates, documents, or passively establishes a situation: rather, it attempts to intervene in the situation as an element providing thrust or rectification. To put it another way, it provides discovery through transformation.2 |

To discover through transformation is to also trust the viewer. In the film, Eusi Kwayana, who serves as a sort of literary critic commenting on Martin Carter’s poetry, says that the task of the poet is to “make reality clearer to the rest of us,” but not by overexplaining things. Instead, Carter was “taking the people’s experiences, refining them, giving them back to the people, nurturing them.” Later in the film, to the sounds of drums and a flute, Carter reads, “I come from the n****r yard,” while we see gorgeous slow-motion tracking shots of the slums of Georgetown, mostly in reversed positive.

The inverted colors emphasize the opacity of images, while the narrative poem tells us of a man “moving in darkness stubborn and fierce.” The sequence gathers circular pans inside the huts, blurred shots of the ghetto landscape, a collection of textures—bumpy ground, wooden walls, stone paving—fragmented spaces, highly contrasted colors, irregular shapes. Distorting, disfiguring, to reach another form of clarity. Or, as Stefano Harney and Fred Moten said, “Clarity implies, here, a kind of darkness, a radical complication of tint, a pigment suitable for grounding, yes, an opacity whereby we see the real with and through the real.”

In a sequence dedicated to the second letter from prison by Carter, we see bars on windows, barbed wire fences, high walls, and tiny holes. The film collects barriers to sight but insists on seeing against all odds. The cinematography incorporates the difficulty of seeing into the vision itself, creating exquisite compositions of blinding lights and profound darkness—until we see a fluid moon among moving shadows, and the film becomes pure experimental abstraction. The oneiric quality of The Terror and the Time makes us think that the Victor Jara Collective was not dreaming of changing the world but dreaming to change the world. For them, dreaming is an action. It is a meaningful, even an urgent political act, as a task for poets and filmmakers alike. Composing those dreamlike images and sounds is a way of struggling not only through cinema, but with cinema, in the sense that only a film could fight that way. For the viewer and listener, The Terror and the Time is neither a historical lesson nor a political statement, but a material, living experience that swallows our whole body and makes us dream together. Not dreaming of changing the world. Dreaming to change the world.

Interviewing Rupert Roopnaraine in Guyana, Monica Jarine and Andaiye allow him to elaborate a brief theory of revolutionary cinema, in tune with Solanas and Getino:

JARDINE/ANDAIYE: Do you think that the working class will find this film difficult to understand? ROOPNARAINE: Undoubtedly. In terms of what we have been saying about the films shown in the commercial cinemas, how can it be otherwise? The film will be difficult and unusual because the Guyanese and Caribbean working people have been denied exposure to films of this kind. We are struggling against film-viewing habits and expectations formed over decades. It is a question of making available to the public alternative types of film language. And what we’re talking about will involve many long years of work. You know, even after the Cuban revolution had become a fact and the Cuban people were becoming conscious of what socialism was, they went right on seeing the Mexican and Hollywood films until the blockade in 1961. We are hoping that this film will contribute to the cultural struggle here in Guyana by opening the possibilities of different types of film language, by demonstrating what a cinema in the service of the working class is capable of. |

The Terror and the Time is a constantly changing film, with interspersing rhythms, tones, and camera and editing styles. It is as if the essayistic, violent, furious rhythm of the first part of The Hour of the Furnaces could coexist—sometimes indistinguishably—with the poetry, lyricism, and contemplative pace of The Sons of Fierro (Fernando Solanas, 1972–78) in the same film. A film where, as film theorists Jean-Louis Comolli and Jean Narboni wrote, “politics is not the enemy of beauty.”3 At times, the juxtaposition is extreme, as in a much-celebrated sequence wherein archival material of luxury products advertising is edited together with a butcher cutting meat, and another of a man lying in the street and asking for help while his fellow citizens pass by. In engaging these three different sources of imagery, turbocharged by sound, we struggle with what we see and hear, moving together, changing with the velocity of the film.

In another sequence, a sort of musique concrète reminds us of the strange soundtrack of the first Comunicado Cinematográfico del Consejo Nacional de Huelga, a superb counterinformation short made by film students on strike alongside workers in Mexico in 1968. To this tune, soldiers march on the street, and suddenly an image from another time flashes for one second on the screen. It’s Escrava Anastácia, the representation of an enslaved woman with a punitive iron facemask, who is venerated in Brazil as a popular folk saint.

The Terror and the Time’s associations are internationalist at its core. As Eusi Kwayana says in the film: “It’s one thing to be teaching the theory of the international working class in terms of political theory and historical terms. But it’s another thing for working people to feel a link with other people and other fighters in other lands.” That’s why we see, in another tumultuous sequence, African people dancing and raising arms, then bats, then machine guns. Then Vietnamese people dancing, holding hands on a march, smiling, carrying cannons. Dancing, smiling, holding hands with a comrade or a gun to defeat the imperialist enemy. To the sound of a repetitive, heavy African drumming, everything is part of the same struggle.

Defined by programmer Jonathan Ali as “a sui generis triumph of anti-colonial cinema,” The Terror and the Time—from the project to the film to the process of distribution—is a late blooming of Getina and Solanas’s conception of Third Cinema. In recent decades, the Global North has misinterpreted Third Cinema as all political cinema made in the so-called Third World. But the term is much more restrictive and demanding—it is a revolutionary concept, not a broadly descriptive category. Solanas and Getino referred to a global reorientation of militant filmmakers who were making films as direct interventions in a given historical situation around 1968.

Reflecting on the process of making and distributing The Hour of the Furnaces with Grupo Cine Liberación, Getino and Solanas’s “Towards a Third Cinema” manifesto states that the passage from Second Cinema (auteur cinema, all the “new waves” around the globe, Cinema Novo in Brazil, Generación del 60 in Argentina) to Third Cinema would encompass a radical alteration in every aspect of cinema, from production to exhibition. They advocated for change in the following:

- How we conceive authorship (from individual auteurs to collective processes)

- Technical aspects (using “amateur” 16mm instead of “professional” 35mm)

- Filmmaking (every project should now be an alliance between filmmakers and social movements)

- The film itself (no longer a complete and closed object, but an open work for the workers to use, which could mean, for instance, the reordering of the 16mm reels of The Hour of the Furnaces to serve specific purposes)

- Distribution (not the commercial and festival circuits, but a series of autonomous, even clandestine projections organized by the same group who produced the film, or by their allies, in spaces like unions, universities, and militants’ backyards)

- Exhibition (every projection of Third Cinema should be a political act, involving the choice of the film for particular goals, and including deep conversations during each reloading of the projector)

- Audiences (the intended audience is not the regular moviegoer, but people involved in the struggle, who now become “actors-participants”)

This is what they call “the film act”:

| Each projection of a film act presupposes a different setting, since the space where it takes place, the materials that go to make it up (actors-participants), and the historic[al] time in which it takes place are never the same. This means that the result of each projection act will depend on those who organize it, on those who participate in it, and on the time and place; the possibility of introducing variations, additions, and changes is unlimited. The screening of a film act will always express in one way or another the historical situation in which it takes place; its perspectives are not exhausted in the struggle for power but will instead continue after the taking of power to strengthen the revolution.4 |

Upon completion, The Terror and the Time went to festivals like Rotterdam, Leipzig, and Cinéma du Réel, and had public screenings in Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, and the UK. Third World Newsreel distributed it throughout the U.S. Although sparse in frequency, numerous screenings followed, engaging audiences with the film and in anti-imperialist campaigns in various countries. In Guyana, due to the heavy censorship, it was nearly impossible to show it. A few years later, the conditions in the country deteriorated, with government censorship, persecution of opposition leaders, and brutal control of the media. The situation would culminate with the assassination of Walter Rodney, an extraordinary historian, academic, and political activist, who was by that time a member of the Working People’s Alliance, the same party of Eusi Kwayana, Cheddi Jagan, and Rupert Roopnaraine.

After Rodney’s death, Lewanne Jones went back to the unused material of The Terror and the Time and composed a short film called In the Sky’s Wild Noise (1983) to tell Rodney’s story from the point of view of the working class. The short was the second and last piece signed by the Victor Jara Collective. In 1978, Roopnaraine became the leader of the Working People’s Alliance. This recalls what Colombian filmmaker and critic Carlos Álvarez, in a text titled “El tercer cine colombiano” (“Colombian Third Cinema”), published the same year: “Today we fight with cinema in our hands. Tomorrow the conditions change, and we will fight with another thing. We are not immutable. That is to say, this cinema, like all activities in Latin America, will have to be extremely dialectical.”5

Near the end of the film, a title card says, “End of Part 1 – Colonialism,” but there are still five minutes until The Terror and the Time really ends. Initially intended to be a teaser for the other parts, this last sequence now shines as a raw, angry, beautiful deployment of pure cinematic energy, made of flames and slow tracking shots; the leisure of the white bourgeoisie and the struggle of the working people; sudden stillness and dynamic motion; a woman working the fields and another woman fixing her hat by the pool. Guyana’s contradictions explode against each other in heavy percussion music and fast montage. The drumming comes and the dreaming starts over. And it will never stop, unless we let this incendiary oeuvre sit still in a vault somewhere—or remain unseen in a forgotten corner of the internet.

Victor Guimarães is a film critic, programmer, and teacher based in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. He is currently a columnist at Con Los Ojos Abiertos (Argentina). His work has appeared in publications such as Cinética, Senses of Cinema, Kinoscope, Desistfilm, La Vida Útil, La Furia Umana, and Cahiers du Cinéma.

Notes

1. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations from this essay come from the extraordinary brochure On the Films of the Victor Jara Collective, a collection of texts by members of the Collective and other writers, edited by Lewanne Jones and published by Autonomedia in 2023.

2. Solanas, Fernando, and Octavio Getino, “Towards a Third Cinema: Notes and Experiences for the Development of a Cinema of Liberation in the Third World.” In Scott MacKenzie, ed., Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures: A Critical Anthology. University of California Press, 2014, 360.

3. Comolli, Jean-Louis, and Jean Narboni. “Nos années Cahiers.” Catalogue du Festival International du Film La Roche-sur-Yon, 2011, 46.

4. Solanas and Getino, “Towards a Third Cinema,” 370.

5. Álvarez, Carlos, “El tercer cine colombiano.” Cuadro 4, primer trimestre de 1978, Medellín, 48.