These Amazing Shadows is the story of the National Film Registry. The documentary is scheduled to air on PBS December 29 as part of the Independent Lens series. PBS is also distributing the documentary in DVD and Blu-ray formats.

The 88-minute film was conceived, written, produced and directed by Paul Mariano and Kurt Norton for their company, Gravitas Docufilms. Christine O'Malley, whose work with Patrick Creadon includes Wordplay and I.O.U.S.A., also produced the film.

The National Film Registry is part of the Library of Congress. It was founded in 1989 under the auspices of the National Film Preservation Act passed by Congress the previous year. The mission delegated to the Registry is to restore and archive 25 motion pictures per year that have fit the criteria of "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant." Films are chosen based on recommendations made by fiction and documentary filmmakers, critics and fans.

Films must be at least 10 years old to be eligible. Content varies from a 1893 black-and-white film of a blacksmith at work to Thriller, the long-form Michael Jackson music video by John Landis; classics such as The Godfather and The Wizard of Oz; the amateur Zapruder film documenting the assassination of President John F. Kennedy; and a treasure trove of documentaries, including Hoop Dreams, Harlan County USA and Salesman.

These Amazing Shadows integrates images culled from films in the Registry with observations made by 65 individuals, including Barbara Kopple, Steve James, Rob Reiner, Gale Anne Hurd, Christopher Nolan, Leonard Maltin, Debbie Reynolds and Dr. James Billington, who heads the Library of Congress.

The story behind the production of These Amazing Shadows is like the script for a feel-good Hollywood movie, where a seemingly impossible dream comes true. Paul Mariano was a criminal defense attorney, who served in a Northern California public defenders office for 27 years. Kurt Norton was a private investigator, who specialized in death penalty cases, frequently in collaboration with Mariano.

After Mariano retired from law, he and Norton formed Gravitas Docufilms and initially produced "mitigation videos" for defendants in death penalty cases. They later collaborated on Also Ran, a 2006 behind-the-scenes documentary about the special election that resulted in recalling California Governor Gray Davis from office in the wake of the state's energy crisis.

Documentary spoke with Mariano about the process of making These Amazing Shadows.

What inspired you and Kurt to undertake this ambitious endeavor?

Paul Mariano: In 2007, we read an article about the National Film Registry and the films selected that year. That sparked our interest. We were both stunned by the statistics about films which were part of our culture that have been lost forever. Approximately half of the films made in the United States prior to 1950 no longer exist. As many as 80 to 90 percent of all American silent films have been lost forever. Those losses seemed unimaginable to both of us.

How did you get this project into motion?

We contacted Steve Leggett, who is the coordinator for the National Film Preservation Board at the Library of Congress. I explained that we wanted to come to Washington to discuss an idea we had for producing a documentary about the role the Registry plays in our culture. He was extremely positive from day one, and was incredibly helpful from the beginning through the completion of our production.

How did you begin production after that initial conversation?

We began by researching the origins and background of the National Film Registry and the National Film Preservation Board. We interviewed Steve and some archivists at the Packard campus in Washington, DC. That armed us with important insights about what they did, the passion they felt for their mission and why preserving yesterday's and today's films for tomorrow's audiences is important.

You were drawing on an amazing trove of potential content. What was the process for choosing the clips that you used?

The American film heritage is an incredibly rich and diverse landscape. We wanted to accurately represent the tremendous diversity of films archived by the Registry. They include avant-garde and classic Hollywood movies, documentaries, home movies and industrial films. We chose clips from films that reflect that diversity, while telling stories about our people and culture, for better or worse.

How did you and Kurt decide whom to interview?

That process began with Steve Leggett introducing us to John Ptak, Bob Rosen, Betsy McLane, Del Reisman and other members of the National Film Preservation Board. Some of those interviews led to introductions to actors, directors and other filmmakers, including Rob Reiner, John Singleton and Amy Heckerling. The interview process continued with Kurt and I persistently asking people who we felt could shed light on this important issue to share their thoughts and feelings.

Did you assemble people who are featured in your documentary in groups, or are these all individual interviews?

Kurt and I and our cameraman traveled to wherever they were. We did interviews in people's homes and workplaces, where they felt comfortable and relaxed while sharing their stories, thoughts and feelings.

Did they choose the films and subjects on which they commented, or did you and Kurt ask them to address particular topics?

We had a topic we wanted to explore with most people we interviewed, but we allowed them to lead us into areas they felt passionate about.

Tell us about your collaboration with the cinematographer who recorded images during interviews.

Frazer Bradshaw was the cinematographer. He has an impressive list of credits. We had utmost respect for Frazer, and trusted his skill and judgment. That included him choosing the right angles and composition for augmenting words being spoken by different individuals. We told Frazer that we wanted These Amazing Shadows to have a filmic look. We asked him to shoot interviews from an off-axis angle, augmented with dramatic lighting that looks and feels right for the individual and subject. He did a magnificent job.

In what format was These Amazing Shadows produced?

The interviews were recorded digitally in high definition.

How many hours of content did you record?

We shot somewhere between 100 and 120 hours of interviews.

Where has These Amazing Shadows been seen so far, and what are your plans for the future?

These Amazing Shadows premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. It was subsequently featured at festivals in Boulder, Cleveland, Ashland, Tiburon, Hawaii, River Run, Newport Beach, Seattle, Stony Brook and Indianapolis. There have also been screenings at theaters around the country. PBS is distributing the DVD.

What are you doing about archiving These Amazing Shadows?

The documentary and outtakes are archived on hard drives, which are stored at several different locations.

What lessons have you learned from this experience?

I have learned that filmmaking is truly the art form of the 20th and 21st centuries. Film tells us so much about our culture and history. Losing it would be like losing part of ourselves. Preserving films saves both our memories and cultural heritage. The incredibly dedicated people who have a passion for saving yesterday's and today's films for future generations deserve our unending gratitude.

Bob Fisher has written more than 2,500 articles about narrative and documentary filmmakers over the past 50 years. He has also written extensively about the importance of archiving yesterday and today's films for future generations.

2011 Jacqueline Donnet Emerging Documentary Filmmaker Award--Ethics Amidst the Fog of War: Danfung Dennis

The chopping sound of helicopter blades hovers over a black screen, feeling less like an entrance than a continuous perpetual drone, a cloud that does not lift. The soldiers of Echo Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment are launching the largest helicopter offensive since Vietnam: 4,000 Marines countering the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan. A group of soldiers kneels low in loose sand, their weapons in hand; they resemble a football squad posing for a yearbook photo. A young soldier smokes a cigarette, the background blurred out of focus in shallow depth-of-field: It is a quiet, contemplative moment, except for the ever-present, ominous whir of the helicopter blades. Men rush to load up the SeaKnight helicopters, running through a grey haze of stirred desert dust. Over a montage of soldiers crammed side by side, facing each other in the helicopter's carry and a harnessed-in tail-gunner covering the field below, the battalion commander intones, "Your conscience should be clear and your honor should be clean." The men land and set out as the helicopters fly away. The assault begins amid the rubble of a marketplace. You are so close you can see the rounds feeding into the assault rifles and hear the shouts of men over the chaos of ricochet gunfire all around them.

Photojournalist Danfung Dennis, embedded with the men of Echo Company, is capturing footage for his first film; he does not know what this film is going to be or what it's going to be about, but he has been here before. Not exactly this location, but in this situation. As a war photographer who has covered conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, famine in Ethiopia and political disruption in Kenya, he is accustomed to going places and seeing things most of us would prefer to hold at a distance. Having made the transition from still photographer to filmmaker, Dennis brought with him the same motivation that initially convinced him to document humankind's most brutal realities.

The result of Dennis' first foray into filmmaking, Hell and Back Again, premiered at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival, where it won the World Cinema Jury Award and the World Cinema Cinematography Award. And Dennis himself has been awarded the International Documentary Association's 2011 Jacqueline Donnet Emerging Documentary Filmmaker Award. Hell and Back Again is indeed a remarkable achievement; personal and deeply psychological, it merges and balances cinematic aesthetics with journalistic intent.

"It was an evolution going from photojournalist to filmmaker," says Dennis. "I think I am still going through that process, and I don't think they are mutually exclusive.

"At first I thought I could shoot still and video at the same time," he explains, "but I quickly realized that it's two completely different thought processes. When you're trying to capture decisive moments [in photography], you have to stay very fluid, thinking of capturing the crescendo of a scene, whereas when you are creating a film, you have to look for those extended moments and try to bring the viewer into it in a much more full way. I am working with a lot of these ideas of immersion to convey emotion in the most visceral sense."

What unfolds through Hell and Back Again is a juxtaposition of the combat experience in Afghanistan with life in small-town North Carolina, as viewed through the eyes of Sergeant Nathan Harris, a returning soldier severely wounded just days before the end of his deployment. The camera reveals a man who is strong and confident, an exceptional leader in the field--and also lost, depressed and anxious at home with his wife as he recovers. The images throughout are graphic and disturbing, sometimes beautiful, but above all, intimate.

This intimacy derives from a level of access that every documentary filmmaker strives for and that Dennis achieved through his unique position and extensive experience, which provided him with crucial insight. "You have to request specific units, specific locations," he explains. "Otherwise, the generic embed is not very interesting. You'll just be given a tour of very positive stories for the military. But, if you dig deeper and you know where and when things are happening, you can be with the right unit at the right time."

When the soldiers returned, Dennis went to the homecoming. Sgt. Harris, however, did not get off the bus. Two weeks previous, he had been transported out of Afghanistan and was recovering in a US Naval hospital. Dennis made contact and was invited to Harris' hometown, where he was introduced to Harris' wife, Ashley, and their friends. Dennis recalls, "Harris would say, ‘This guy was over there with me,' so I was accepted into this rural Baptist community, and I essentially lived with Nathan and Ashley."

Back home, Harris was struggling with his own physical and mental recovery. "It crystallized," Dennis maintains. "The experience of war is not simply what happens on the battlefield, but what happens when you get back."

The situation a war photographer puts himself in is much akin to that of the soldier, both in combat and upon the return home. "No one really understood what I had just seen," Dennis says. "You come back from this world of life and death, the blood and dust, to one where everything seems almost mundane and trivial." Among the landscapes of drive-throughs and outlet malls, only Harris and Dennis could see and taste the blood and dust.

"He knew that I understood what he had seen," Dennis says, "and I think that's why he let me into that side of him. Most people won't reveal it. So by going through the same experience that he went through, he allowed me to document those dark, more invisible struggles when he got home."

In portraying this experience, Dennis would abide by journalistic principles; he would avoid determining a conclusion, providing exclusively substantiating documentation. "As a photojournalist, I learned to bear witness and let events unfold in front of the lens truthfully and honestly," he explains. "I brought the same methods and ethics to combine them with the narrative of documentary film."

Perhaps if it were explicitly critical, Dennis would not only be stepping over the journalistic boundary, but also losing some of the power of his narrative. Instead, he appears to subtly question. "It's looking at what kind of world we live in back in the US: Big-box Walmarts," he observes. "Is that what we are fighting for? I don't think I give solid conclusions, but I think I try to raise as many questions as I can."

This objectivity establishes a trust between the filmmaker and subject. Dennis did not intervene in the story; he merely placed himself there as a witness. "I never actually sat down with Nathan and asked, ‘How were you feeling at this point? Did you have this memory come back to you then or there?' None of that. He simply had to trust me to tell a story."

Justin Ridgeway is a Toronto-based writer and art consultant.

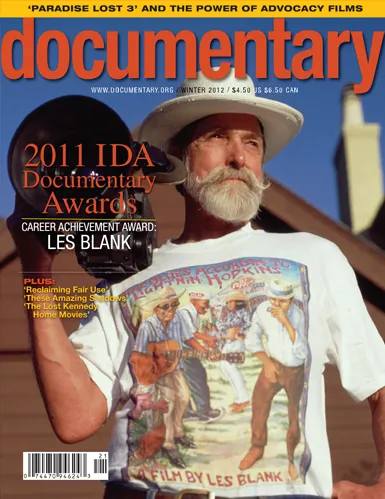

Like almost all of the subjects he has explored in his sublime, handcrafted works over six decades of filmmaking, Les Blank is a master of an art that one must go off the beaten path to find. Even while he has been honored with retrospectives at lofty locales like the Museum of Modern Art in New York, he still hawks his wares--DVDs, t-shirts, posters and pins--that he totes in a well-traveled suitcase.

Burden of Dreams, which he made with longtime collaborator Maureen Gosling, is perhaps the greatest film about filmmaking--or even the creative process--ever made. And yet, it's more than that. It immerses us as much in the Peruvian Amazon and the culture of its native inhabitants as it does in the careening imagination of Les' longtime friend, Werner Herzog. And it seems clear that the film played a role in helping the indigenous people of that region gain legal rights to their land.

A Poem Is a Naked Person is perhaps the greatest film about rock 'n' roll and American music that you will likely never see. This film about Leon Russell can only be viewed in a non-commercial screening in Blank's presence--the aftermath of a lawsuit between Russell and the producer. "He never did tell me why he didn't want it shown," says Blank. "I try not to mention the name of the film or the subject [in publicity] because he's sued me a couple of times to stop me."

These two opuses merely hint at the vivid cultural universe explored in Blank's body of work. Other musicians profiled in his films include Lightnin' Hopkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Lydia Mendoza, Tommy Jarrell, Flaco Jimenez, Boozoo Chavis, Mance Lipscomb, Francisco Aquabella and Clifton Chenier. And then there are films about garlic, gap-toothed women, a cowboy artist and, of course, Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe. Legendary folklorist Alan Lomax, a friend and an influence of Blank's, called his short The Sun Gonna Shine "One of the three most important films on the South." Blank seems to have followed his own American muse and captured magic along the way (he was even a camera operator on Easy Rider).

Blank is a soft-spoken, deferential, visionary wayfarer. Throughout his body of work is a consistent, gold-standard high-wire act; he is fully present with the subjects and yet completely out of the way in the final film. The result is a rare breed of intoxicatingly intimate anthropology that brightens not just a corner of the world rarely seen by outsiders, but in most cases a defining and largely underappreciated element of American culture.

Blank is currently at work on two long-term labors of love, like all his films--one about the late, legendary British documentary filmmaker Ricky Leacock and the other about Alabama outsider artist Butch Anthony.

Blank once said of the people at the heart of his films, "I become them." Documentary recently spoke to the 2011 IDA Career Achievement Award honoree about that process, his career and whether or not Herzog really ate his shoe.

Did you originally think you were going to work in narrative features?

Les Blank: That was my plan from the very beginning. When I saw Ingmar Bergman's Seventh Seal, that sealed the deal. I decided then and there that I wanted to be around the making of films that had this impact, that were, spiritually and emotionally, deeply involving the very fiber of your being. Even if I couldn't make that film myself, I wanted to be in the presence of people who were making it, and help them with their vision.

And where did the shift to documentary take place?

While at USC, I took a course in documentary film and was very inspired by this whole medium. All I knew about documentary was what I had seen as a kid. They had short subjects and films called Bring 'Em Back Alive, where they would go into the jungle and catch these large pythons and things. This to me was thrilling, but I didn't think of being a filmmaker. It just seemed [like] too much magic, and I didn't know where to begin. There weren't film schools I knew of at the time, so it never was a consideration. But then an ethnographic filmmaker came through town and showed a film to our class about the people of the Kalahari Desert called The Hunters. The filmmaker, John Marshall, followed this group of men who were out hunting for their village, and if they failed to come back with an animal then everybody would starve to death. I thought, "To be able to make a film like this would be a great way to live one's life."

When you started out, did you feel that doing the industrials or working on the military films was contrary to your politics?

My main goal was just to learn filmmaking and eventually do something creative with filmmaking. So I learned the technique of shooting--and because the people I worked for were very cheap, I ended up doing all the work, like the sound recording, the camera work, writing the narration...Once I learned my craft, it was no longer very tolerable. In fact, I was about to lose my mind from the inanity of it all. And it starts coming out in some of the films I did, like Chicken Real, about the chicken industry.

The films I like are bottomless; you can't really prove the exact depth of their feeling. And there's vitality to the subject, like the Lightnin' Hopkins film. All I can do is grab at essences of what I think is there, but I never feel like I've gotten to the bottom of it.

With The Blues According to Lightnin' Hopkins, the format was kind of organic-things flow out of something, there's really no reasonable arrangement of sequences and substance, it's just all merged from one to the next. It's more like music. It took a while to arrive at this style.

From Les Blank's 1969 film The Blues According to Lightin'Hopkins. Courtesy of Flower Films

But do you feel like in making that film, you discovered some of your own style, since that seems to be reflected in your other films as well?

Yeah. I think having seen how this can work, I have used this approach in other films. Not always successfully, but it worked especially well with the Lightnin' film.

So Werner did genuinely eat his shoe?

He ate every piece of that shoe, except for the sole. He figured you eat chicken and you throw the bones away, so therefore he could throw the sole away. I took a piece just to see what it was all about, and I couldn't get it down. My vomit reflex kicked in.

I asked him to come to my office the next day just to see if he was still alive and try to wrap up what it was all about, and that's how you got the speech. He was looking real ashen, but he was still standing and he talked about how the modern world needs new imagery, that stale images were going to cause us to die off like the dinosaurs.

It was the experience of making Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe that gave me the courage to go with him down to Peru [to film Burden of Dreams]. I realized he had star quality, and that if I could get back alive and sane, I would have an interesting film, no matter what happened. But the trick was getting back alive...and sane.

I was thinking of Americans whose body of work offers something comparable to what you've done, and Alan Lomax was the first person to come to mind. Do you feel like he or his work was a big influence?

That's true. I greatly respect his work, but I felt he had kind of a narrow approach to making art, or to expressing the scene in the way I was doing. For instance, he told me that a good ethnographic cameraman would never use a zoom, never shoot short takes. They would get a wide-angle lens, put the camera on the tripod, turn it on the subject and step away. The scene should be interpreted by people who knew what they were doing. The subjective viewpoint of the cameraman would just muddy up the waters. I told him he was nuts. And we would argue over things like that.

That's a crucial kind of debate you don't hear so much in documentary any more. Visual anthropology has died out a lot since then. Now, unfortunately, it seems like you're more likely to hear a debate over whether to use animation, rather than how to be accurately or ethically ethnographic.

Yes.

There's always seemed to be an American folklorist aspect to what you're doing. Is that conscious, or not so strategic?

I tend to film things I find fascinating or interesting. I guess those are things that folklorists also look at. I really don't have guiding principles. I just drift to what I find interesting and also what I think audiences will like to see. I try to find a fresh way of looking at the world around me and making some sense of it--hopefully something positive, something lasting that the world would want to see 100 years from now.

Taylor Segrest is writer and co-producer of Darwin (2011). He is currently at work on his next film, a narrative feature about the most tragically forgotten rebellion in American history. He is also a contributing editor for Documentary.

The 2011 IDA Awards Issue Winter 2012

In which we recognize Les Blank for his achievements throughout the year, and honor 2011's best in documentary filmmaking.

Features

Columns

Meet the IDA Documentary Award Nominees: Kelly Duane de la Vega and Katie Galloway--'Better This World'

Editor's Note: Kelly Duane de la Vega and Katie Galloway's Better This World has been nominated in the Best Feature category at this year's IDA Documentary Awards, to be held at the Directors Guild in Los Angeles on Friday, December 2. Below is an interview we conducted with Richardson last August.

Synopsis: How did two boyhood friends from Midland, Texas wind up arrested on terrorism charges at the 2008 Republican National Convention? Better This World follows the journey of David McKay (22) and Bradley Crowder (23) from political neophytes to accused domestic terrorists, with a particular focus on the relationship they develop with a radical activist mentor in the six months leading up to their arrests. A dramatic story of idealism, loyalty, crime and betrayal, Better This World goes to the heart of the War on Terror and its impact on civil liberties and political dissent in post-9/11 America.

IDA: How did you get started in documentary filmmaking?

Kelly Duane de la Vega: I majored in fine arts, with an emphasis in photography.I was taken with documentary still photographers like Robert Frank, Lee Frielander and Mary Ellen Mark. After I finished school, I worked as a photojournalist for a weekly newspaper in Portland, Oregon, and shot several photo essays while traveling through the South. While I was reasonably happy with my still work, I longed to include the conversations I had along the way. I eventually found my way to filmmaking, taking a couple of film classes at a struggling film nonprofit in San Francisco, but mainly learning by doing, and by editing with Nathaniel Dorsky on my film Monumental. Nathaniel helped me understand the cinematic language that I never had a real chance to study.

Katie Galloway: I worked in print and radio before I got into filmmaking. By the time I got interested in making documentaries I already knew I loved working with audio--the ability to weave in atmospheric sound and especially people's voices was, for me, a thrilling additional ingredient in storytelling. During my time in radio--mainly at KPFA /Pacifica--I was also a huge fan of documentaries: Werner Herzog, Barbara Kopple, DA Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, Errol Morris and Les Blank were all early influences. Discovering the richness of sound led organically to a desire to try my hand at visual storytelling. I did a one-year program in documentary production in New York, learning a bit about shooting, editing and directing. The rest is history.

IDA: What inspired you to make Better This World?

KDDLV & KG: In January 2009 The New York Times published a story about the controversy around the arrest of two young men from Midland, Texas, for the possession of eight homemade bombs at the Republican National Convention. The story immediately captured our imaginations. With the government claiming that McKay and Crowder were domestic terrorists bent on murdering or maiming cops and Republican delegates, and the defense asserting that the young men had been unduly influenced by a radical activist 10 years their senior and were victims of a overzealous government intent on taking them down as a score for the post 9/11 domestic security apparatus, there was clearly a mystery to unravel. Once we flew to Minneapolis and met several of the amazing cast of characters and the plot thickened, and we knew we had to make a film.

IDA: What were some of the challenges and obstacles in making this film, and how did you overcome them?

KDDLV & KG: While our initial intent had been to cover the case vérité-style, it quickly became clear that a central piece of the story was what had already happened between three men: the accused, David McKay and Bradley Crowder, and the older radical activist, Brandon Darby. They spent a lot of time together in the six months leading up to McKay and Crowder's arrests. Telling a story largely set in the past forced us to re-imagine our cinematic approach. Creating the back-story was a long and arduous process (looking through hundreds of hours of surveillance footage, listening to dozens of hours of jail-house phone calls, seeking out images, documents and audio of FBI interrogations through the Freedom of Information Act...), but it was ultimately incredibly enriching and rewarding.

IDA: How did your vision for the film change over the course of the pre-production, production and post-production processes?

KDDLV & KG: As is so often the case with documentaries, we were following a story that was not yet resolved. Over two years of interviewing FBI agents, attorneys, defendants, family members, jurors and journalists, we were repeatedly surprised by the twists and turns we discovered. At several points we were forced to re-evaluate our perspectives...and debates between us about personal morality and responsibility versus government accountability and meanings of entrapment regularly erupted in the field and the edit room. We wanted to allow audiences to share those experiences, and we committed early on to building the twists, moral ambiguity and big questions we wrestled with into the film.

IDA: As you've screened Better This World--whether on the festival circuit, or in screening rooms, or in living rooms--how have audiences reacted to the film? What has been most surprising or unexpected about their reactions?

KDDLV & KG: Better This World has inspired intense discussions around the country and internationally, encouraging people to grapple with what we view as one of the critical tensions of our time: between civil liberties and security in a post 9/11 world.

IDA: What docs or docmakers have served as inspirations for you?

KDDLV: Katie laid out several above; here are several of mine: Brother's Keeper, When We Were Kings, Man on Wire, Hoop Dreams, several from Herzog, and the work of Nathaniel Dorsky and still photographer Robert Frank.

Better This World will be screening August 12 through 18 at the IFC Center in New York City, and August 26 through September 1 at the Laemmle Sunset 5 in Los Angeles.

For the complete DocuWeeksTM 2011 program, click here.

To purchase tickets for Better This World in New York, click here.

To purchase tickets for Better This World in Los Angeles, click here.

Meet the IDA Documentary Awards Nominees: Peter Richardson of 'How to Die in Oregon'

By Katie Murphy

Editor's Note: Peter Richardson's How to Die in Oregon has been nominated in the Best Feature category at this year's IDA Documentary Awards, to be held at the Directors Guild in Los Angeles on Friday, December 2. Below is an interview we conducted with Richardson last May.

How to Die in Oregon, which won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival, follows individuals whose lives have been deeply affected by Oregon's Death with Dignity Act, which legalizes physician-assisted death for terminally ill patients who request it. It's not an easy film to watch, and at screenings of this heart-wrenching and intimate documentary, filmmaker Peter Richardson admits that the ending of the film is often greeted with silence. This is an understandable reaction to such an emotional and powerful experience; as you become invested in the subjects of the documentary, you can't help but think of how, as Cody Curtis puts it in the film, we are all terminal. There are no easy answers when it comes to how to die, no matter what the state or country, but with How to Die in Oregon, Richardson hopes to at least make asking the questions just a little easier.

I spoke with Richardson before he left for Hot Docs, and we discussed his filmmaking process, how he handled such an intimate and sensitive issue with his subjects, his advice for beginning filmmakers and more.

IDA: What inspired you to make a film about the Death with Dignity Act?

Peter Richardson: Inspiration for the film came to me out of the blue, really. It was 2006, and I'd just finished my first film, Clear Cut: The Story of Philomath, and the day I was leaving for Sundance with that film happened to be the day that the Supreme Court ruling upholding Oregon's [Death with Dignity] law was announced. The law had been challenged by the Bush Administration and it went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in a split decision to uphold the law. So I just knew that would be the next film I would make.

IDA: Beyond living in Oregon, do you have any personal connection to the law?

PR: It didn't come from a personal experience I had with the law; it was really just thesynergy of that moment. I realized that this was a film that really needed to be made because it was such an important issue and it hadn't been done yet. And it would not be an easy film to make, just from a practical perspective. It would probably need to be made by someone who lived in the state. Living in Oregon, I felt an almost responsibility as a documentary filmmaker to tell this story, and the way that I wanted to tell it would require a really long-term commitment to following the lives of a number of different people. So it was all of those different pieces coming together.

IDA: What were your goals in how you wanted to approach such a controversial topic?

PR: I knew pretty early on that I didn't want to focus on a political or theoretical conversation about this issue; I really wanted to focus on the personal stories of people who were considering using this law. That was what I was most interested in, and I also felt that there are many other forums and there have been many other expressions of the theoretical aspects. Where I felt there was a real lack was in, "Let's get down to how this actually plays out in people'slives." There was a journalistic sense that that's a story that needs to be told, but also to me as a filmmaker, this is an intensely personal choice that people are making--to get this medication and then to potentially use it--and I thought that would best be explored in a documentary. That was the film I was interested in making--about these personal stories, not about a number of different experts talking about this issue more theoretically or sharing their opinions.

IDA: How did you find your subjects?

PR: When I began researching this issue I discovered pretty early on that most of the people in Oregon who use the law or consider using the law have some contact with an organization called Compassion and Choices. I contacted them and said, This is the film I'd be interested in making; would you be willing to, on my behalf, make introductions to people you have contact with and I can speak to them about participating in the film? That's pretty common for them. When there's coverage in the US or abroad about the law, because it's an initiative that's popping up in other countries and other states, they're frequently contacted because they do have access to people in the state who are considering it. So they agreed to make the introductions on my behalf. That led to the initial conversations with potential interviewees and subjects of the film that evolved to kind of personal relationships with those people as the filming went on.

IDA: Cody in particular really allowed you incredible access. Was there ever any concern from her or her family or on your end with you filming such intimate moments?

PR: I think that as a filmmaker that would be the biggest challenge of the film--the fact that I was entering into very intimate moments at very sensitive times, maybe even the most sensitive times in people's lives. That was one of the central questions I asked myself, and I think a lot of documentary filmmakers ask themselves going into these situations: I really believe in this film, and this story needs to be told, but what is my presence going to mean for the people I'm filming with, and can that be a constructive process, not only for the film that I believe in, but for them intheir own lives?

I really questioned whether or not it was appropriate for me to ask of these people what I would ultimately need to ask in order to make the film. What I discovered really early on was that they felt very strongly about having their stories told and being able to share their experiences with other people, and they saw the film as their way of getting to do that. That was very reassuring, and that's what I encountered with Cody and her family as well, was that willingness and openness to share.

But initially, with Cody's family, that only came from her. Her husband and her children were pretty [much] against the idea of participating in the film for the obvious reasons I think most people would be, but Cody felt very strongly about it, so they just went along with it initially.

As the process unfolded and they saw how I would be a presence in their lives and that I could have a minimal footprint while I was filming and would be respectful of their privacy when it was asked of me, ultimately they told me that they found the process of being in the film a very constructive one, not only in the final product of the film itself but also in the actual filmmaking process. Cody's son and daughter referred to our interviews as "free therapy," and I couldn't ask for anything better as a filmmaker to have them say that.

But that was one of the essential challenges any time you make a very personal film likethat. Frequently these kinds of films are made about someone in your family or are a very personal experience so there's less risk in the way that you're asking less of the people you're filming with, but in this I was a total stranger in these people's lives and that was a real challenge for me. It's a real testament to the courage of these individuals that they would give me such access. Certainly there were times when I was told that I couldn't film and that was always kind of a ground rule thatwas understood, but it's still remarkable the degree to which they were so open.

IDA: How have audiences reacted to your film?

PR: I've found the general audience reaction to be very positive. It is a very difficultfilm and I try to acknowledge that. At the beginning of screenings, I thank people for coming because I know that, one, it's not an easy film, and two, it's not an easy film to watch in a theater with a lot of people. But almost every screening I've been at has been full, so as difficult as this issue is--not only physician-aide in dying but the larger issue of death and dying--as much as people don't want to confront it, and there's this idea that "Oh, well, this isn't something we want to talk about in our society," I also think that this is something people do want to talk about. There is a hunger for a real and genuine conversation about death and dying--not in a morbid way or in a way that is anything but people wanting to have a dialogue about something we're all going to face. As Cody says, "We're all terminal." It's not something we can avoid, and that's scary, but also, it's why this film does need to exist and why we do need to have this conversation--because ultimately we are all terminal. There's very frequently silence at the end of screenings, and that's to be expected. This is a very, very emotional and powerful experience, but I also think it can be a really transformative one, and that's been my experience with touring around at festivals with the film.

IDA: Do you have any political or social goals for the film?

PR: I don't have any really political goals because I wasn't coming from a certain political perspective on the issue. In terms of social goals, one was just to share this story. There's a kind of journalistic mission with that: the idea of sharing a story about a very important social issue and a groundbreaking law that exists in Oregon, and how that might inform a debate in other states or other countries where the law is considered-- like Vermont, for instance, where wedid a screening. So there's that immediate goal that's directly tied to a specific issue.

My larger hope with the film is that it fosters a conversation among those who see it about this larger issue of death and dying that I think is critical for our country to have, no matter where you fall on this specific issue. You can totally disagree with it, and I hope still find a lot of value in seeing the film and hearing these stories and hopefully feel like you can have this kind of conversation with your own loved ones. I actually get that a lot from people who've seen the film, about the conversations they've then had with family members--not specifically about death with dignity but just about this larger issue of death and dying and what would they want, and what are their views on it, and "We've never talked about this" because nobody does want to talk about it. So I think the film can be a catalyst to that kind of conversation.

IDA: Do you have any ideas for your next film?

PR: I have some ideas but nothing I've landed on. I want to get this one out into theworld and clear my head a bit before I start on the next one.

IDA: Do you have any advice for beginning documentary filmmakers?

PR: Go make documentaries. That's my single piece of advice. You can totally make a documentary or a feature film out of the trunk of your car, which is basically what I did with both of these films, at least initially.

There are incredible stories all around you. If you want to be a filmmaker, go make films. That was the best advice that I received in college. It was on a field trip for part of a sound design class and it was really inspiring, to just go make films. If you want to be a filmmaker, I think that's the best thing you can do.

How to Die in Oregon airs May 26 on HBO.

Katie Bieze is a graduate student in the Film and Video program at American University and works as a graduate fellow at American University's Center for Social Media. She graduated from Duke University in 2009 with a BA in literature and certificates in documentary studies and film/video/digital.

Meet the IDA Documentary Awards Nominees: Tatiana Huezo of 'The Tiniest Place (El Lugar Mas Pequeno)'

Editor's Note: Tatiana Huezo's The Tiniest Place (El Lugar Mas Pequeno) has been nominated in the Best Feature category at this year's IDA Documentary Awards, to be held at the Directors Guild in Los Angeles on Friday, December 2. Below is an interview we conducted with Huezo last August in conjunction with her him having been included in DocuWeeks 2011.

Synopsis: This is a story about mankind's ability to arise, rebuild and reinvent itself after surviving a tragedy. It is also a story of a people that have learned to live with their sorrow; of an annihilated town that re-emerges through the strength and deep love of its inhabitants for the land and the people; of a tiny place nestled in the mountains amidst the humid Salvadorian jungle.

IDA: How did you get started in documentary filmmaking?

Tatiana Huezo: I started working after I finished school. I collaborated as a cinematographer with an American documentary filmmaker, in the Sierra of Veracruz. I realized that most of the local families there were made up of two women and one man. I was curious about that. I wanted to learn more about a family model so different from mine; I wanted to learn if it was possible to share the love of a man with another woman. Some time later, I went back and started to search for a family to work with. I found two women and a man who had been living together for 40 years; the women were sisters.

It was all about patience. It took a whole week before they started to talk to me; every day I sat waiting in silence while the women were taking corn kernels off the cob. One day they started to talk to me. Then I asked them if I could move into their home for a while. I was accepted and that's how my journey into the lives of others started, a journey that lets me share stories that I care about.

IDA: What inspired you to make The Tiniest Place (El Lugar Más Pequeño)?

TH: I was born in El Salvador and raised in México. The Tiniest Place started the day my grandmother took me for the first time to the village where she was born. That afternoon we reached Cinquera, after driving on a dirt track that gradually became narrower and greener as we approached what I anticipated would be a tiny village behind the mountain. Finally, we arrived at a nearly empty town. While walking, I was approached by an old woman who hugged me, yelling, "Rina, you came back! You don't look a day older than the last time you were here!" But my name is not Rina and I had never seen that gushing lady before.

Then I entered the town church. There were almost no religious images; instead there was a helicopter's tail fitted to one of the walls and a large row of pictures of very young people with their respective candles on the floor. I felt a blow to the stomach. The people in the pictures were all guerrilla fighters killed during the Civil War, and many of those faces mirrored mine. And I thought, "Had I lived this war, where would I be right now?" That moment is still in my head and undoubtedly was the beginning of this project.

IDA: What were some of the challenges and obstacles in making this film, and how did you overcome them?

TH: One of the challenges was to capture cinematically the enveloping atmosphere of the tropical rainforest that surrounds Cinquera. Sometimes we had to walk for hours at night, in total darkness, to get the ideal shots of certain landscapes at daybreak. More than once we got lost amid the fodder, and the day would break before we were set up.

We also had to gain acceptance from the local people, to have them get used to us. A long stay was the key for things to flow naturally and for me to have enough access to my characters.

During the editing process, the main challenge was keeping a balance between the two main forces contained in the story: light and shadow, life and death. I think I was able to meet my goal.

IDA: How did your vision for the film change over the course of the pre-production, production and post-production processes?

TH: I had plenty of time to think about the way I wanted to tell this story. I knew that I didn't want on-camera interviews. I also knew that I wanted to build up the rainforest as an important element. And I knew that the main discourse of the film was going to be comprised of two independent elements, image and oral speech, although I wasn´t sure if that was going to work.

During shooting I found new characters who enriched the film, like Rosi, "The Messenger." The idea of filming a big storm that would gather all the characters arose as well. There was an important confluence of chance, luck and planning in the production process.

Post-production was one of the most intense stages. First I had to build the oral discourse that forms the core of the movie, then I had to look for the images that would cover it, and finally I had to organize the powerful third discourse that came out. That search has been a great learning experience for me.

IDA: As you've screened The Tiniest Place (El Lugar Más Pequeño)--whether on the festival circuit, or in screening rooms, or in living rooms--how have audiences reacted to the film? What has been most surprising or unexpected about their reactions?

TH: The audience is surprised that this is a war story told in a different way from what they are used to. They are surprised by how terror and violence are present throughout the movie, but without images to illustrate them.

The screenings always evoke a great emotional response; I'm surprised at how close the audience feels to the characters. I've been told beautiful things about the force of life and the human spirit.

IDA: What docs or docmakers have served as inspirations for you?

TH: I have a lot of influences, not only documentaries but also fiction. The directors I always revisit include the Dardenne brothers, Johan Van der Keuken, David Lynch, Gus Van Sant, Werner Herzog, Raymond Depardon, Michael Haneke, José Luis Guerin, Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Dvortsevoy, among many others.

The Tiniest Place (El Lugar Más Pequeño) will be screening August 19 through 25 at the IFC Center in New York City and September 2 through 8 at the Laemmle Sunset 5 in Los Angeles.

For the complete DocuWeeksTM 2011 program, click here.

To purchase tickets for The Tiniest Place (El Lugar Más Pequeño) in New York, click here.

To purchase tickets for The Tiniest Place (El Lugar Más Pequeño)in Los Angeles, click here.

This year’s nominees for Best Documentary at the Gotham Awards include:

- Better This World

- Bill Cunningham New York

- Hell and Back Again

- The Interrupters

- The Woodmans

Other documentaries vying for awards include Being Elmo: A Puppeteer’s Journey, Buck, and Wild Horse, Wild Ride, which will compete for the 2nd Annual Gotham Independent Film Audience Award alongside narrative nominees The First Grader and Girlfriend.

For a full list of this year’s nominees, visit gotham.ifp.org.

DOC U ON THE ROAD

Made possible by a grant from

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Doc U: Can Your Doc Really Change the World?

In Association with:

|

Monday, December 12, 2011

Doors Open: 6:30pm

Discussion & Audience Q&A: 7:00pm - 8:30pm

Join the speakers for a reception following the discussion.

POV

20 Jay St.

Brooklyn, NY 11201

IDA Members: $5 • General Admission: $10

Seating is limited so buy your tickets now to be guaranteed admission.

Join IDA now! For discounted admission prices and more!

Can a documentary really change the world? These days it seems as though more and more doc-makers are giving it a try. But if you’re hoping to use the power of film to advocate for solutions to complex social issues and to urge people to take action, how can you make sure that your documentary has the greatest possible impact? What kinds of outreach and marketing campaigns are the most effective? How can you best partner with non-profits to get your message out? What do funders and broadcasters expect from documentary filmmakers? And what’s the best way to build a successful social action campaign? The panel of filmmakers, organizational changemakers, and communication experts we’ve assembled address all of these questions and many more. What they have to say could change the way you think about changing the world.

On December 12, join producer/director, and co-founder of Doculink, Robert Bahar (Made In L.A.), as he moderates a discussion with Diana Barrett, founder of The Fledgling Fund, filmmaker Rachel Libert (Semper Fi: Always Faithful, Boomtown), Cynthia Lopez, Co-Executive Producer of POV, and Academy Award®-winning filmmaker Roger Ross Williams (Music by Prudence), on the ways and means of producing documentary films with the potential to effect real change.

Join us after the discussion at a reception with your moderator, panelists and fellow audience members.For more information on IDA's Doc U: documentary.org/doc-u

Doc U is the International Documentary Association's series of educational seminars and workshops for aspiring and experienced documentary filmmakers. Taught by artists and industry experts, participants receive vital training and insight on various topics including: fundraising, distribution, licensing, marketing, and business tactics.

Special support provided by:

|

If you live anywhere but Southern California, you’re probably starting to feel pretty left out. And with all the great Doc U events we’ve been hosting this past year, we totally get it. That’s why we’re taking Doc U on the road! Doc U on the road is made possible by funding received from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Our next stop is Brooklyn, NY, where our Doc U will again focus on answering the question: Can Your Doc Really Change the World?

If you’re hoping to use the power of film to advocate for solutions to complex social issues and to urge people to take action, how can you make sure that your documentary has the greatest possible impact? What kinds of outreach and marketing campaigns are the most effective? How can you best partner with non-profits to get your message out? What do funders and broadcasters expect from documentary filmmakers? And what’s the best way to build a successful social action campaign? The panel of filmmakers, organizational changemakers, and communication experts we’ve assembled address all of these questions and many more. What they have to say could change the way you think about changing the world.

On December 12, join producer/director, and co-founder of Doculink, Robert Bahar (Made In L.A.), as he moderates a discussion with Diana Barrett, founder of The Fledgling Fund, filmmaker Rachel Libert (Semper Fi: Always Faithful, Boomtown), Cynthia Lopez, Co-Executive Producer of POV, and Academy Award®-winning filmmaker Roger Ross Williams (Music by Prudence), on the ways and means of producing documentary films with the potential to effect real change.