Jill Godmilow, the iconoclastic filmmaker whose attempt to tell the story of Poland’s Solidarity movement while barred from the country resulted in a documentary that broke with the form and earned her the equivalent of a knighthood from the Polish government 30 years later, died at her New York City home on September 15, aged 81. Her death was confirmed by her older sister, Dr. Lynn Godmilow. The cause was a combination of metastatic breast and lung cancer.

At the time of her death, Godmilow was professor emerita in the Department of Film, Television, and Theatre at the University of Notre Dame, which she joined in 1992.

One of the great teachers and practitioners of American independent cinema, Godmilow’s films, which include Far From Poland (1984), Antonia: A Portrait of the Woman (1974), Waiting for the Moon (1987), and Roy Cohn/Jack Smith (1994), challenged the porous border between fiction and nonfiction, creating a new and unique cinematic syntax. As a theorist of documentary film, Godmilow is also known for her widely disseminated 1999 essay, “What’s Wrong With the Liberal Documentary,” and her 2022 book, Kill the Documentary: A Letter to Filmmakers, Students, and Scholars.

Joan Godmilow was born on November 23, 1943, in Philadelphia, the younger daughter of Beatrice (Schlaifman) and Herbert Godmilow. Her father was a dentist, and her mother worked in the Philadelphia school system. She graduated from Springfield High School in 1965 and then entered the University of Wisconsin/Madison, where she obtained a degree in Russian literature.

Godmilow moved to New York City after college, began calling herself Jill, and quickly found work as an assistant film editor, notably on The Candidate (1971), directed by Michael Richie and starring Robert Redford.

That same year, she completed her first film, Tales (1971), a collaboration with performer Cassandra Gerstein that was made with an all-woman crew. This well-received “performed documentary,” which focused on the ways people recount their sexual experiences, presaged her subsequent theoretical challenges to the form as well as her continued interest in human sexuality.

Her second film, Antonia: A Portrait of the Woman (1974), co-directed with Judy Collins, focused on orchestra conductor Antonia Brico, a pioneer who defied but never fully overcame the prejudice against women at the podium. The subject permitted Godmilow to combine her feminism with her filmmaking, a leitmotif that courses through her oeuvre. Antonia earned rave reviews, was named one of the ten best films of the year by Time magazine, received an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary, and was added to the National Film Registry in 2003.

Her next few projects, including The Popovich Brothers of South Chicago (1977), Nevelson in Process (1978), and The Odyssey Tapes (1980) (the latter two co-directed with Susan Fanshel), saw Godmilow focus on the essence of and context for artistic expression.

Godmilow’s most influential book.

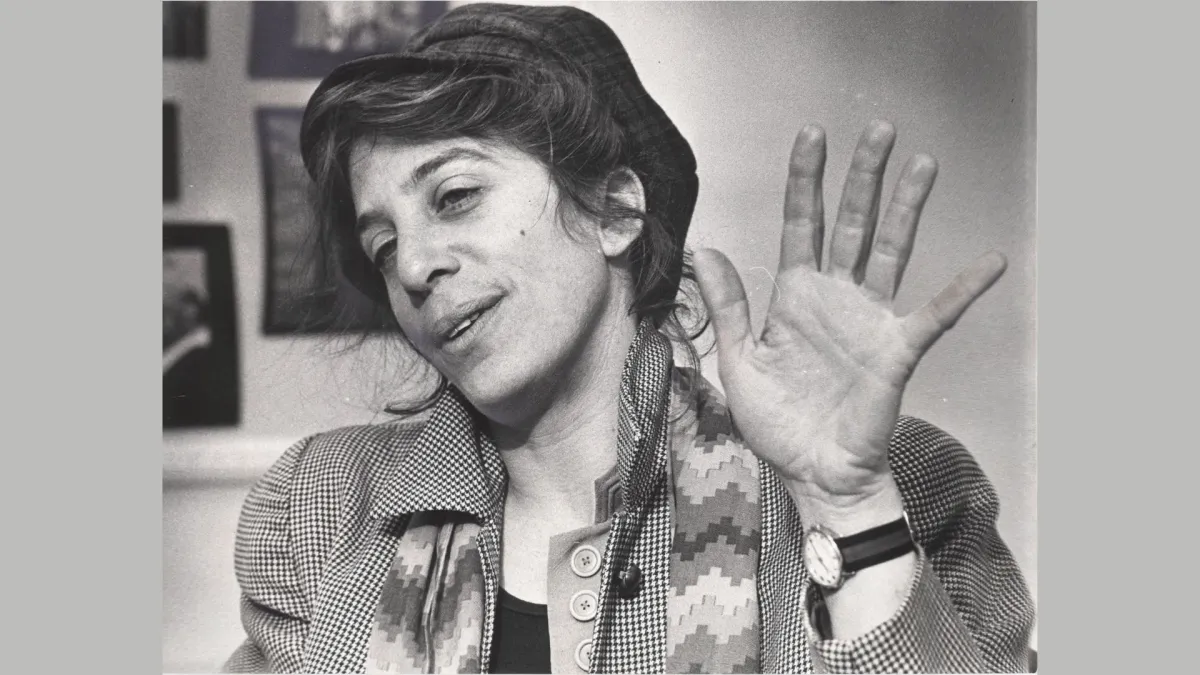

Jill Godmilow (L) and Sandra Schulberg (R) at Anthology Film Archives. Courtesy of Sandra Schulberg

Equally drawn to philosophy, Godmilow gravitated to the thinker William Gass, coiner of the term “metafiction,” and used his theories to create a philosophical framework for her fiction and nonfiction filmmaking. By the time Godmilow found herself grappling with how to tell the story of Poland’s unfolding Solidarity movement, she was already there, making a film about the avant-garde theatre director and theorist Jerzy Grotowski, With Jerzy Grotowski, Nienadówka (1980).

Grotowski’s theatre experiments aimed to bring performers into direct contact with the spectators and to turn the performances inside out, so that the actor becomes a vehicle for an inner truth. When workers struck the Gdansk shipyards, she wanted to film the strike as it was unfolding, but Grotowski urged her to return to the U.S. and raise the necessary funds first. She did so, but with the world fixated on Gdansk and myriad journalists seeking entry, Godmilow was unable to obtain a visa. This conundrum gave rise to a film that remains a landmark in the history of American cinema: Far From Poland.

Godmilow’s stratagem, devised with intellectual comrades Susan Delson and Mark Magill, was to film actors reading and re-enacting verbatim interviews and articles from Solidarity pamphlets. Informed by Gass and Grotowski’s theories, Godmilow’s film signaled the truth of the artifice, making clear that the storytelling is aware of its own technique.

Far From Poland marked a turning point in Godmilow’s career, convincing her that fiction, if not pretending to be “truthful,” could allow her to comment on issues and people of interest to her in a manner that conformed to her intellectual principles. Two people of interest were Gertrude Stein, the avant-garde author, and Alice B. Toklas, Stein’s companion and muse. In 1985, she and Mark Magill began to develop the story for what would become Waiting For The Moon (1987).

Inspired by Cubism, Godmilow wanted to fracture the concept of a “biopic” and counter any expectation of “realism,” celebrating Stein’s experimental writing while making her own consciously self-conscious work of art. Waiting For The Moon, which starred Linda Hunt as Toklas and Linda Bassett as Stein, was quite experimental, but it connected with critics and audiences, winning the Grand Prize at the 1987 Sundance Film Festival.

Throughout her career, Godmilow sought to recontextualize artistic works and elevate text to the level of art. In Roy Cohn/Jack Smith (1994), she adapted Ron Vawter’s eponymous performance piece—in which he played both the right-wing politico and the Flaming Creatures filmmaker—into a dizzying conversation that stressed the continuity between those two figures, both of whom died of AIDS in the 1980s.

Similarly, her next films, What Farocki Taught (1998) and The SCUM Manifesto (2017), operated as metatextual homages. What Farocki Taught is a shot-for-shot replica—but in color and in English—of Harun Farocki's 1969 B&W German film, Inextinguishable Fire, about the invention of Napalm. In The SCUM Manifesto, Godmilow, Joanna Krakowska, and Magda Mosiewicz paid homage to the 1976 French film made by Carole Roussopoulos and Delphine Seyrig that was inspired by Valerie Solanas’s infamous text of the same name. Godmilow’s Polish-language version of The SCUM Manifesto is an exact replica of the French film and doubles as her own feminist homage, echoing Solanas’s plea to decolonize the female mind.

I am not at all interested in trashing all documentaries, but I am interested in examining the assumptions they operate under, primarily that these are necessary and useful truths a citizen is entitled to.

Jill Godmilow, Kill the Documentary: A Letter to Filmmakers, Students, and Scholars

Such an intellectual approach to her work ultimately led Godmilow to find a home in academia. As colleague Maria Tomasula recalls, “Jill landed at the University of Notre Dame in 1992 with the force of a resistance fighter and the curiosity of a New Yorker suddenly transplanted to the hinterlands. Jill and Notre Dame were an odd couple, but the relationship worked—largely because she managed to get Notre Dame to accede to her principles and, as a result, changed campus culture for the better.”

In response to the misogyny she and other female faculty members faced, she founded WATCH, an organization that created a handbook by and for women, containing information on promotion, tenure, and campus culture. WATCH wasn’t an acronym, though Godmilow sometimes joked that it stood for “Women’s Alliance To Chuck Hegemony.” She also co-founded NDPFSA, the Notre Dame Progressive Faculty/Staff Alliance, which continues to this day.

Tomasula asserts that Godmilow’s effectiveness as an organizer stemmed from her sense of rebellious fun, coupled with clear thinking on which university policies needed to be challenged so that faculty and students could freely express and share progressive political beliefs. At the conservative Catholic institution, during a time when many kept their sexuality and politics in the closet, she used her faculty bio as a one-line totem: “Independent filmmaker focusing on feminist, gay, labor, and art issues, primarily in nonfiction formats.” Besides inculcating her students with a rigorous aesthetic, she challenged them to think about how filmmaking can constitute an act of resistance.

In 2014, Jill Godmilow launched a controversial attack on a film that had been lauded by critics and was nominated for an Oscar for Best Documentary, Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing (2012). In her IndieWire essay, “Killing the Documentary,” she essentially accused the filmmaker of being unethical.

As she wrote, “No critic seems to be examining what there is to learn from this ‘unruly documentary artivism’—the new moniker for non-fiction films which assert their status as both art and activism and thus the license they claim to refuse compliance with certain classic codes of ethical documentary filmmaking.”

Eight years later, Godmilow expanded these ideas in her book, Kill the Documentary: A Letter to Filmmakers, Students, and Scholars (Columbia University Press, 2022), which served as a culmination of her thinking and practice over 50 years of filmmaking.

As she writes in the book’s opening chapter:

“I am not at all interested in trashing all documentaries, but I am interested in examining the assumptions they operate under, primarily that these are necessary and useful truths a citizen is entitled to. I am interested in how they implicitly describe us, the viewers, as caring citizens. I write to disclose what assumptions about us are not examined, and how the explicit use of realism covers all these sins. You could call it a handbook for correcting these errors and for suggesting other ways to use your cinema voice to ask the right questions without cover of ‘realism’ or ‘truth.’”

Doubling down on these convictions, Godmilow made two last films: On the Domestication of Sheep (2019), a witty, animated film and powerful feminist manifesto; and For High School Students—Notes and Images from The Viet Nam War (2022), co-written with Erick Stoll. She posted the latter film online for free, arguing that its 45-minute runtime was ideal for classroom teaching and that it was a needed corrective to the 18-hour Ken Burns/Lynn Novick PBS series.

As her next and final project, Godmilow decided to investigate her own sexual experience from a feminist’s point of view and to explore the complicated relationship that women have to orgasm. The film, Ecstatic Orgasm, was unfinished at the time of her death.

In 2010, when Jill Godmilow thought she might soon die of cancer, she asked me to take over the Laboratory for Icon & Idiom, Inc., the nonprofit organization she and I had co-founded in 1984, now better known as IndieCollect. That year, we changed its mission from producing films to saving films. Since then, IndieCollect has archived thousands of precious indie film negatives, restored nearly 100 of them (including What Farocki Taught), and launched RescueFest.

Thanks to IndieCollect, literary executor Richard Herbst, and the collaboration of the Academy Film Archive and Anthology Film Archives, Jill Godmilow’s film legacy will live on. We will celebrate that legacy on January 18, 2026, when Anthology Film Archives and IndieCollect will co-host a public tribute in her honor.