The Feedback: Chuck Schultz and Judah-Lev Dickstein’s ‘When My Sleeping Dragon Woke’

In 1993, Chuck Schultz received a call from an actress named Sharon Washington, who had been told by a friend that he could help her tell the story of how she grew up in a New York City library. He didn’t make a film at this time, but three years later they started dating. A few years after that, they got married. Then, in 2017, as Sharon began writing a one-woman show based on her life, Chuck thought this was finally the perfect opportunity to make a film. A mix of interviews, animation, and verité, When My Sleeping Dragon Woke follows Sharon as she faces the difficulties of creating a play about her life, delving into her upbringing, her relationship with her parents, and the process of letting go of the idealized narratives of childhood.

Directed by Chuck Schultz and co-directed and edited by Judah-Lev Dickstein, the film was scheduled for a DocuClub WIP screening in March 2020, making it the first screening canceled when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. In lieu of an audience feedback session, Chuck and Judah had a talkback with Dara Messinger, DCTV’s director of programming and engagement and longtime DocuClub NY partner, and Toni Bell, IDA’s former manager of filmmaker services. The talkback session was moderated by Opal Bennett, who was named co-producer of POV soon afterward.

When My Sleeping Dragon Woke premiered at Heartland International Film Festival in October 2022, where it won the Best Documentary Feature Premiere Award. In February 2023, it screened at the Sedona International Film Festival. As for Sharon? She co-wrote the book for New York, New York, which premiered on Broad in April 2023. In May 2023, Sharon was nominated for her first Tony for Best Book of A Musical for her work on New York, New York.

We sat down with Chuck and Judah to hear about their process of making the film, their unusual DocuClub experience, and their hopes for the film now that it’s complete.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: What was the process like of working with Sharon, who is your wife?

CHUCK SCHULTZ: I was naive going in. At times, it was very easy. She was very willing. When things got really difficult, I had to make decisions like, Hey, I’m not going to bring the camera. I’m not going to film this.

But what would I have done if Sharon didn’t really follow through with the play? That would’ve been so hard. I don’t know if I would have made the film. But I believed in Sharon. I knew Sharon’s story really well and I knew that it would move people. But I didn’t realize, and I don’t think she realized in a way, what was going to happen.

JUDAH-LEV DICKSTEIN: Because I’m a removed third party—I think by design—I am thinking in a more objective way. There were many times when I would say to Chuck, “Why didn’t you get this? I can’t believe you didn’t get this.” I think not having gotten some of those things, which would’ve been moments of good vérité, meant that Sharon respected the boundaries that Chuck was respecting with her. I think that reassured her that the film’s intentions were good.

D: Judah, how and when did you get involved?

JLD: I came on right after the main production wrapped and was on for the interviews, the B-roll, and the animation.

CS: I chose Judah. I asked him to come to the play in New York, and he came. Afterward, Judah and I walked from the West Village all the way up to 42nd Street, and then back down to 39th Street for him to take a train home [to Philadelphia]. In that conversation, we didn’t really talk about working together as much as we talked about ideas for the film. And it was then that I thought, “Maybe Judah’s the right person to cut this.”

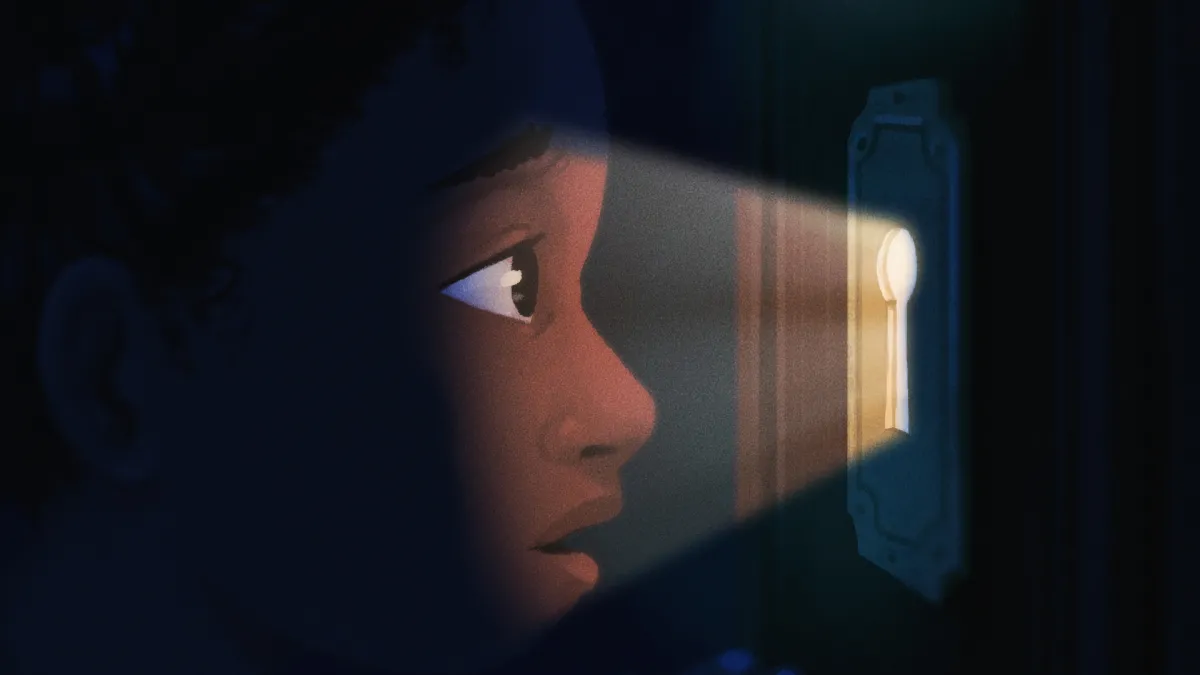

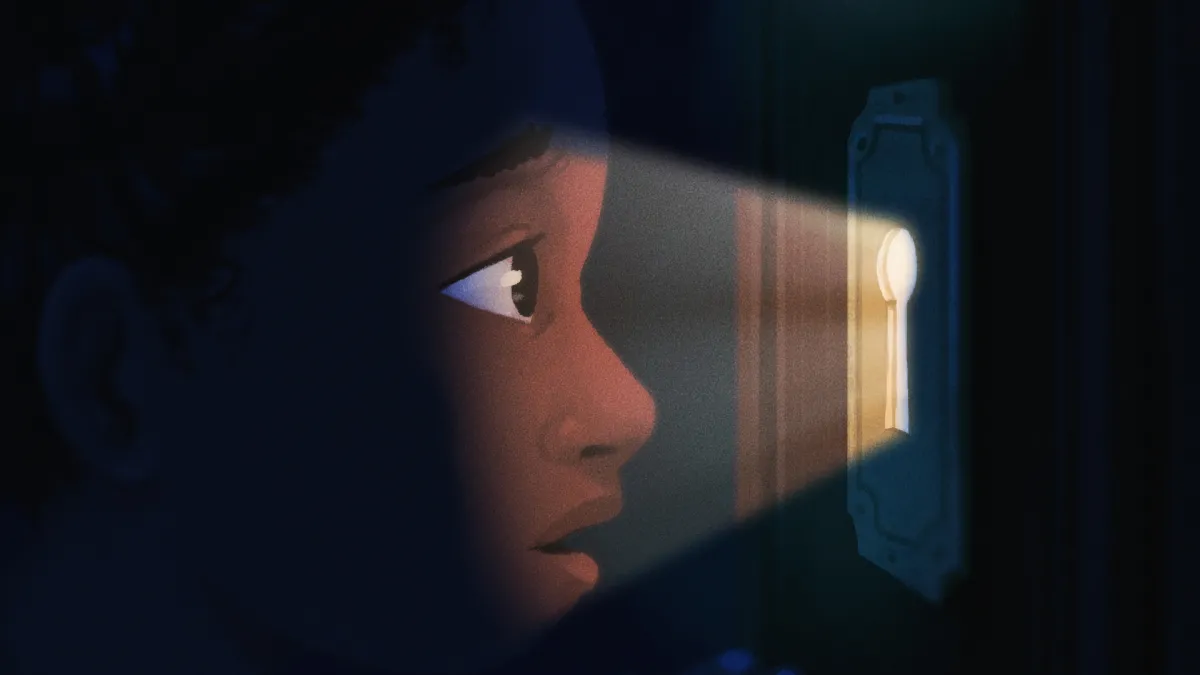

D: How did the animation come about?

JLD: Sharon’s family were not rich people growing up. They were not constantly taking photographs or filming. There’s not a lot of archival of them, and half of the story takes place in her childhood. We had to find a way to represent it, but we didn’t really feel like re-creations were right. The idea of using animation clicked for us as a great way to articulate childhood wonder, but as the film moves on, the tone of the animation can change.

D: You have these three threads that you’re weaving through the film: Sharon’s interviews, animated sequences with narration from the play, and Sharon’s experience writing her one-woman show. How did you strike the balance between all three of those?

JLD: That was the big question of the film. I think we had tried so many times to decide, okay, is this about Sharon’s past? Is this about the making of? They were so inextricably tied together that we tried to make them really feed off each other so that it never felt like it was two parallel storylines, that it felt like one storyline that had multiple tracks.

D: What was something that you really wanted to hold onto, but in the end, thought it best to leave out of the film?

JLD: It was a small moment. We used to open the film with it, but we eventually removed it. Sharon is in her dressing room, getting ready before the show. She’s touching up her makeup, and she stops and she looks at herself in the mirror, and she says the first line of the play. There was something about it that always felt very powerful to me. Ultimately, for structural reasons, we had to lose that. It was a major loss.

D: You had a DocuClub screening that was canceled because of COVID-19. Can you just walk me through what happened next and how you worked around that?

CS: It was a big disappointment. We asked if we might be able to do a virtual screening, but that was something that no one was prepared for. It was too soon. We had a talkback session with Dara Messinger and Toni Bell. Opal Bennett was the moderator. It wasn’t quite what we imagined, but it was very helpful for us.

JLD: They gave us a lot of great notes. I was concerned that the film was just too small or that it wasn’t going to hold the audience, but one of their notes was that we could let it play because it was holding people’s attention. That was a note that made me feel confident that we can live in this world that’s not high drama, but is just world-building and storytelling and character.

CS: That December, I was feeling stuck. That’s when I approached the D-Word for a rough cut screening. Within six, seven days, we got a reply saying that they wanted to talk with us. It turned out it was Susan Kaplan, who was the founder of DocuClub. She wound up saying to us, “Guys, you got a really good film. You don’t have a rough cut.” That was a big boost for us to keep going. And then it had this full circle of participating in DocuClub.

D: What were some other central challenges?

CS: Sharon’s dad’s alcoholism. When does that come out? In the cut that we shared at DocuClub, there was a mention of it by one of Sharon’s college friends probably 15 minutes into the film. Her last line was, “But I never knew about his drinking.” We wondered, Is it too early? Should we wait?

After the talkback with Toni, Dara, and Opal, we realized that we should hold that back. Because that was the big challenge for Sharon—she wanted to write the flip side, but was she willing to talk about her father?

D: What key changes did you make when you went back to the edit room?

JLD: It’s like anyone who’s made a documentary, or any film, knows; once you move one scene, everything after that tumbles down. Moving Sharon’s dad’s drinking back was the change that helped us marry all of the pieces of past and present. It gave us an organizing principle around which to have all of these things. It was very time-consuming, but I don’t know what we would’ve done had that change not been brought to our attention.

D: The film premiered at Heartland in October 2022—what was the experience of finally watching it with an audience?

JLD: It was amazing. It’s not the kind of film where you’re going to hear oohs and aahs, but afterward, during the Q&As, people were crying. They were universally connecting to the film and the story in a very personal way. I think that speaks to the humanity of Sharon and the film.

D: What do you want for the film?

JLD: We’ve screened it with young people and with college students. The conversations that follow are always strong, opinionated discussions. I’ve never felt happier than when watching Sharon talk to young girls after the screening. To see her having these meaningful conversations with these kids was so poignant. The more of that than we can get, the better.

CS: The film was made to make sure her story didn’t stay in the American theater world. Her story can be inspirational, and that’s what I hope the film does.

Gabriella Ortega Ricketts is an archival producer and actress living in Los Angeles with her two cats, Hank and Archie. At IDA, she is the manager of artist programs and a proud member of the union Documentary Workers United. In her spare time, she paints and bakes pies.