“I Will Become My Own Institution”: Alaa Minawi Discusses His Immersive Installation ‘The Liminal’

Courtesy of IDFA

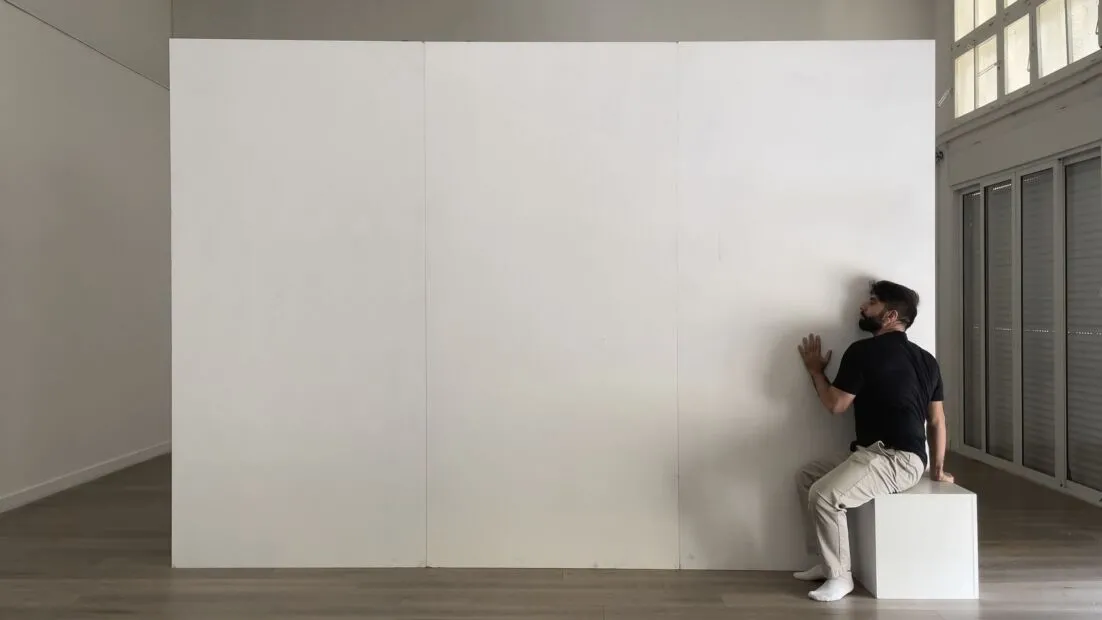

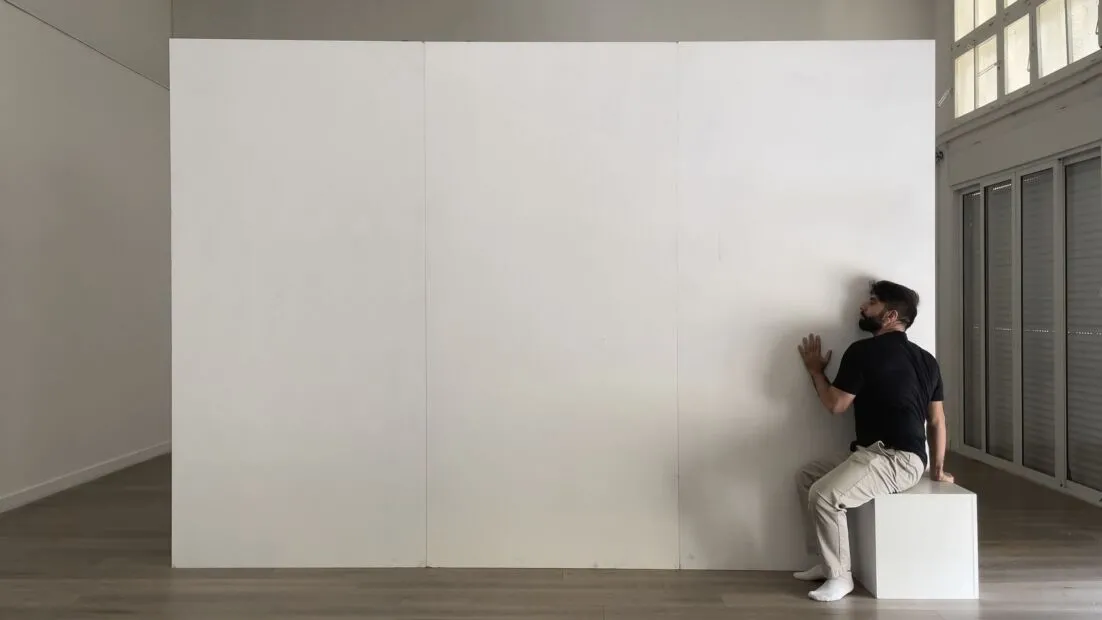

Alaa Minawi’s The Liminal gives an alternative definition of “immersive” from the typical technological, digital one. In his practice, the Palestinian-Lebanese-Dutch interdisciplinary artist explores the possibilities of merging installation and performance art. The Liminal—the first part of his speculative series about Arabfuturism—is a 3.5-meter wall with 24 speakers placed inside, programmed to take the audience on a listening journey.

What seems like a simple white wall is actually a repository of stories of people excluded from traditional power structures, who in turn claim their own spaces and communities “inside the wall.” The piece calls guests to actively listen and bear witness as they move along the wall following the voices, drawing their own physical performance.

The piece premiered as a work-in-progress at IDFA’s DocLab last year, where it won a Special Jury Award for Immersive Non-Fiction. In an expanded version, which premiered at Spring Performing Arts Festival Utrecht in May 2025, Manawi shifted the documentary stories to fictionalized expressions of reality. Those four stories are written by him and Lebanese writer Raafat Majzoub, three of which are inspired by the original interviews. The last expands on a text previously written by Ibrahim Ibrahim Nehm. Of this exhibit, Minawi said, “I wanted to talk about what has happened, directly, about the genocide and our Arab reality. It was very difficult to find the language, until eventually, I felt that poetic, philosophical language is the best way to deal with what is happening.”

Documentary spoke to Minawi after the The Liminal’s IDFA premiere, as he was working on this next iteration. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: How did the idea of the wall come about? Did you start with the idea to create that installation or did the physical manifestation emerge as an idea from your research?

ALAA MINAWI: This installation is part of a bigger research project that I started a few years ago around the topic of Arabfuturism, or reimagining the future from an Arab perspective. But reimagining the future doesn’t mean it would be utopia. Sometimes, reimagining the future will be dystopian.

My projects are affected by sociopolitical realities. I thought, if I’m interested in futurism, what am I interested in? My main interest was in changing power structures. How do we change or reinvent power structures at different levels—the personal, the systematic, the cultural…but also relating to performance: How do I change the power structure between myself and the audience?

I did interviews with people who are considered—within the system, not described by me—as underprivileged. I interviewed people from different communities, including the LGBT community, Palestinians, and other communities that do not have access to dominant power structures in their current form. The main question was: “If you had the power to change something, or if you had the executive power to make laws, what is the first executive decision you would make?”

Then, one interview shifted the whole project—I interviewed a person from the trans community, and she said, “I’m not interested in leading or executive orders, because this power dynamic is the problem itself.” She also told me that what she is interested in is the safe space that she creates for herself and the people around her. That made me think of how people create their own communities, and maybe try to create them underground.

It made me want to research the now, before working on the future. Especially as a Palestinian, or someone from the Arab world, the now is not working, and the now is very violent. So the best thing now is to be in a safe space with communities. Then, the idea of the wall—and living inside the wall—came. We need to find a space where we can gather safely and recreate ourselves, reassemble our way of thinking. So what you see in this installation is basically a group of people that decided to “go inside the wall.” You hear how they live, and what made them live inside the wall.

D: The stories in the wall are from those interviews?

AM: As I was developing it, I wondered, what kind of language do I use? Do I present my interviews as they are, in a documentary form? Or do I create a fiction, a whole story based on interviews, or on my research in general? For IDFA, we had two sides of the wall where people come and hear what is happening. One side was the documentary section, which held the actual interviews that were part of the research. The other side was a fiction story of someone who is inside the wall telling people why they went inside, and what they needed to drop when they did.

I chose two interviews. In one, a Palestinian describes the refugee camp he’s lived in for all his life. There’s so much love, he describes the beauty and the busyness of the camp. He expresses what it means to be a Palestinian at this stage of what’s happening. The second interview is the trans person that I mentioned, and she describes the change she noticed when she transitioned: how she lost privileges in the female body, how she started noticing she is less heard, that when she walks on the street she had to be more careful, how she needs to be smarter and stronger, but sometimes needs to diminish her strength in a room.

D: The process of listening to them is an act of resistance. The piece engages people in a way that cannot be passive—there’s a physicality of the wall and there’s a physicality in the people having to come up and put their ears to it and follow the sound. It’s active, and you’re making people do that at a time when so many people are not listening to these voices. How did you come to the decision of placing the voices inside the wall and put people in that active listening phase?

AM: For all my projects the past five years, you don’t see the physical performer, but rather the absence of the performer, and they are trying to connect with you as an audience member. For this project, first there was no wall, just a mirror, where you looked at yourself and listened to the voices coming in. But then I thought of the wall, because where should we hide but inside the wall? There are so many layers, connotations, and symbols related to walls.

I’m always thinking about how a performance or installation can connect with the audience on a different, deeper level. How do I involve them more than just watching from the outside? First, there’s the idea of proximity, that you as an audience member are not just sitting. Then, there’s the idea of putting your face to the wall itself—there’s almost something childish about it. With the physicality and the coldness of the wall, that experience can initiate emotions and feelings. There is something tactile about it, something about your posture—sometimes comfortable and sometimes not—that is a physical thing happening within the body as it’s going through something. I think that helps a lot in connecting.

Then, there is the listening itself: the idea that there’s one person in a very low voice whispering to you. And then there is the game: actually moving and trying to follow the voice. Each person hears one character, walks with that character from one place to the other for the duration, and then leaves.

You don’t know the other stories unless you come back again. You can almost overhear what they’re saying from time to time, but you wouldn’t understand them because it’s muffled and far away from you, so you’re really focused on your character. I find it beautiful that this person in that wall is talking only to you and telling you that story, and then you’re leaving with that story.

D: The other interesting thing, as we’re talking about immersive, is that it’s also a performance art piece, because even if you’re not listening to the stories themselves, you can watch people as they physically map out the wall.

AM: It’s definitely visually nice for people to see it from outside. That is why I didn’t do any markings on the wall. I could have done drawings or projections, but I wanted it simply to be a plain white wall that is filled with the bodies of the performance. I had the image of Egyptian hieroglyphic drawings in my head, being drawn while people are moving from one place to the other. I was thinking about the composition. It’s aesthetically present in the distribution of the positions where the speaker starts, one up, one down, and then they move.

D: How does this piece fit into your larger series on Arabfuturism?

AM: The Liminal is the first part, and the second, No Man’s Land, is a performance that will happen next year about Arabfuturism. But in order to talk about the future, I really need to talk about the reality, the now. The now is the war and The Liminal; the future would be in the next project, which I start writing soon.

It’s very difficult to talk about the reality that we’re living in a theatrical way. It’s too early for me. It doesn’t mean it’s wrong, I’m just saying I cannot make a performance out of it. The reality is absurd, and so beyond real, that I don’t think I could do anything on top of that. That is why I have difficulty searching for the language, and a way to talk about this that does not diminish it, that actually deals with it, does not hide it away, but also can be accessible at the same time.

D: You talked about this on the intro panel at IDFA’s DocLab symposium—what it is to make art in these times and what people expect of you, especially as an Arab artist?

AM: Going back to recreating power structures, if I want to be accessible to this power dynamic, but need to compromise stuff, I don’t want to be part of it. I create my own theater. If the institution does not allow me to be because of who I am or what I represent, I will become my own institution.

Karen Cirillo is a cultural worker, documentary programmer and producer, and writer. She is currently based in Istanbul, where she creates multimedia work and events, writes, and manages visual projects for UNDP and other organizations.