My earliest memory of the world is of watching. Perched atop giant hard-case suitcases at New Delhi railway station, my small legs swinging over the edge, waiting for the Kerala Express to pull in. The air thick with the smell of samosas and sweat, the ceaseless hum of movement—hawkers, coolies, and families in various stages of departure and arrival.

The train, in theory, was a single entity hurtling south. But in practice, it was a careful choreography of separation—first-class, second-class, sleeper, general. Each contained reality, stacked one after the other, moving in tandem but never quite together. The same journey, but not the same world.

I was raised within the strict architecture of a Malayali Christian household, where morality was delivered in parables and where certainty was a virtue. I was drawn to its contradictions, the silences that hovered at the edges of doctrine. Religion, as it was taught to me, had little space for women except as symbols—obedient, redemptive, peripheral. To question was to rebel, and rebellion, at its core, is an act of seeing differently. My impulse to interrogate and resist the structures that claim authority over meaning found its expression in storytelling. But at that time, I wasn’t sure how to tell stories that are acts of seeing, differently.

The first answer came in 2007 when I was at AJK Mass Communication Research Centre, as a film student at Jamia Millia Islamia University. I encountered Nishit Saran’s Summer in My Veins. The film is an intimate self-exploration of identity, sexuality, and family. Saran, camera in hand, documented the fragile architecture of his queerness, tracing it like a vein under his skin, leading up to that one powerful moment where he came out to his conservative Indian family. This was my first experience of watching a first-person documentary, and I was taken in by how, in Saran’s hands, the camera turned on itself. The camera became both a conduit and a shield.

A year later, I finished my own student documentary, Flying Inside My Body (2008, co-directed with three of my Jamia batchmates, including Sushmit Ghosh, who would become my lifelong collaborator and partner). At its heart, the film is about Sunil Gupta, a queer photographer who turned the lens onto his own HIV-positive body, reclaiming the gaze, resisting erasure. Making the film, became, in many ways, a filmmaker–participant collaboration—though at the time, I’m not sure we fully understood what that meant.

Sunil wasn’t simply the subject of our film; he was a storyteller with a distinct visual language and a practiced understanding of how stories are framed, especially when it comes to representing marginalized identities. Looking back, I see how much we were learning in real time, not just about filmmaking, but about what it means to share authorship, to build trust, and to tell someone else’s story with care. Why Sunil agreed to let four cis-het film-school kids tell his story, I still don’t know. But he did.

Flying Inside My Body went on to have an award-winning journey across several festivals. It was eventually included in the curricula of gender studies in universities, both in India and globally. But at the time, I was preoccupied with a different kind of audience. For the public screenings, I debated inviting my parents. Would they find it too provocative, too unsettling, too willing to ask the questions they had been taught not to? Or would they, despite themselves, see a part of me in it? At that moment, I decided not to. The quiet pact between my parents and me had been simple—film school was permissible so long as it led to an acceptable career “in the media,” followed by marriage at 25. But this film had already unsettled that arrangement.

Working with Sunil was the first time I began to see questions of identity and the politics of the gaze from a perspective I hadn’t considered before. It expanded and complicated my sense of what it means to see, to be seen. The camera, I was beginning to understand, is a fractured eye—capable of looking, but never entirely whole. That paradox has stayed with me, shaping how I approached the complexity of image making.

Rintu Thomas BTS in Kerala. Courtesy of the writer

Thomas BTS in Uttarakhand. Courtesy of the writer

Thomas (back toward camera) BTS in Ladakh. Courtesy of the writer

Eventually, against every instinct telling me not to, I invited my parents to a screening. They sat through it, wordless. That night, when I finally asked them what they thought, my father’s response was unexpectedly measured, deliberate. “In the Bible, homosexuality is sin,” he said. “But these are also people. They have a right to be happy.”

That was all. And that was enough.

Unlike Saran and Sunil, I never turned the camera onto myself. But that night, I learned that the stories we tell are never separate from us. When they’re told with intimacy and a willingness to dwell in complexity, they can shift something in the viewer—soften a certainty, disturb a silence, make room to see the world differently.

After graduating from Jamia, in 2009 Sushmit and I founded Black Ticket Films, a production company dedicated to nonfiction storytelling. I negotiated another deal with my parents: one year to see where the road led. At first, it led nowhere. No commissions, no steady work. We sent out cold emails, picked up odd gigs, and poured whatever we earned back into our independent projects. In that crucible of uncertainty and stubbornness, we built an imaginarium where our first films took shape.

We made Faces (2009), Notes from a Beautiful City (2010), and In Search of My Home (2010)—not because there were opportunities, but because we refused to stop making them. These films stretched the documentary form. Some were visual essays and others drifted like poems, luminous and untamed. And then, some films came from rage. Dilli (2011), about a city skinned and polished to host an international sporting event, while the hands that built it are made to disappear like an inconvenient truth, was one of them. Others were born from longing and a need to imagine a different way of being, as in Timbaktu (2012), which explored food sovereignty and traditional wisdom through a farmer’s bond with her land.

While my parents signed me up on matrimonial sites, our films were making their way through the world. They won National Awards at home, traveled to festivals across continents, received recognition globally and made their way into university syllabi. The recognition helped; it gave us fuel and allowed us to keep experimenting with the documentary form.

We were drawn to the personal, not only for its intimacy, but also for the way it offered political texture, grounding larger ideas in lived specificity. The recognition also made us think more deliberately about purpose. We began to ask not just how to tell a story, but how to make it matter. How a film might serve the people within it, not only as representation, but as something they could use and take forward. At the core was a belief that the work could gently, but persistently, push the world toward what if and why not.

***

We’re in an era where every image is preframed and optimized for algorithms, blurring the line between performance and authenticity. What does it mean, then, to be a documentary filmmaker in this hypermediated world? To frame people already aware of how they are being framed?

I’ve known myself as someone whose realizations about the world often arrived carrying the heat of rage. But it is the women in my life—those I have met, befriended, argued with, held close—who have taught me that rage alone is not enough. That to truly see the world, one must learn to hold its absurdities, its tenderness, its relentless contradictions. From them, I’ve learned that resistance can be wry, that humour can be an ally, that silence can be an armour. And perhaps, without quite knowing it, they shaped the way I frame a story, the way I choose to look.

Maybe that’s also why, when it was my turn, I pointed it toward the spaces I longed to see—female friendships in all their tangled beauty, women in leadership, in quiet defiance, in the choices they made and the rules they bent. Not as metaphors, not as exceptions, but as people—whole, unfinished. Each encounter is a vivid postcard in my mind. A sanitation entrepreneur in Andhra Pradesh, Ventakalakshmi, negotiates patriarchy at home and caste at work. At dawn, she jumps into her truck for the morning rounds, mentally mapping out the week’s fuel efficiency, naturally dexterous with complex math. Her business is an act of reclamation. In a sun-scalded village in Bihar, Pushpa, a village council head, adjusts the lapel mic and warns, “You can ask me anything, but I might not say what you want to hear.”

On a hot afternoon, in the first year of filming Writing With Fire, journalist Suneeta lays down the rules: “You can film me in the field, doing my stories, but not at home.” A year later, the heat has eased, the air is different, and so is she. A quiet offer, a shifting threshold: “Do you folks want to come home, shoot with my family?”

Nonfiction is a beautiful mess.

And messy is also how I’d describe the cinema I grew up watching—an unruly blend of whatever ’80s Hindi films the cable TV programmer happened to throw into the mix colliding with the delightful cinematic worlds of Sathyan Anthikad, Fazil, Sibi Malayil, Priyadarshan, I.V. Sasi, on DD Malayalam. It was an unfiltered diet of stories, devoured without pattern or restraint, and I loved every bit of it. Yet, across the disparate landscapes of mainstream cinema, one thing remained strikingly consistent: women were everywhere and nowhere at once. If modern, they were proud; if rebellious, swiftly tamed; if central to the plot, drained of all interiority.

Somewhere between looking for those spaces and creating them, I found my own.

I also realized that over time, I’ve become less interested in just telling stories and more in interrogating the power that shapes who gets to tell them—and how. We’re in an era where every image is preframed and optimized for algorithms, blurring the line between performance and authenticity. What does it mean, then, to be a documentary filmmaker in this hypermediated world? To frame people already aware of how they are being framed? For women, as in the physical world, the digital sphere is not neutral. It is negotiated, policed, contested. Who gets to be visible? On whose terms? At what cost? My preoccupations about representation, about how we shape technology and how it shapes us, came together in my first feature documentary, which I co-directed with Sushmit.

Writing With Fire is a story about power. It is a film about truth, justice, and the quiet audacity of an all-women’s newsroom in Uttar Pradesh, seen through the eyes of three of its journalists. After 14 years of print journalism, they chose to go digital, stepping into the unpredictable, untamed landscape of the internet. Sushmit and I were drawn in by the collision of ancient and new forces. On one hand, women from caste-marginalized communities, pushing against a centuries-old system that was built to erase them, and on the other, the internet’s wild, borderless space, a new kind of power.

A Khabar Lahariya meeting in Writing With Fire. Courtesy of Music Box Films

Suneeta Prajapati in Writing With Fire. Courtesy of Music Box Films

In the summer of 2016, we were invited to film the early conversations of this independent news agency, Khabar Lahariya, as it was directing its transition. What I remember most fondly from that first day of filming a team meeting in Chitrakoot is the soundscape of the room full of women—the wit, the intellectual rigour, the fierce arguments, the jangle of bangles as hands impatiently sparred with words, and the sharp and playful rhythm of the Bundeli repartees.

The women at Khabar Lahariya were no strangers to being filmed. Several short documentaries and print features had already been made about them. So when we first sat down with them, they gave us what they thought we wanted—distilled versions of their lives, a coherent narrative arc, a protagonist, a resolution. But we listened to the silences and were more interested in those parts of their stories that peeked through the ellipses. And so began a journey that would take us all five years to complete, folding many journeys in one.

Our interest in this story was, in part, an inquiry into the act of looking itself. The women we were filming were chroniclers themselves, women who had spent years training their own gaze on the world. And now, framed through our camera, another layer emerged: a gaze upon a gaze. What does it mean to record someone recording? To construct a narrative around those constructing their own? The boundaries of authorship blurred—who controlled the image, who dictated meaning?

One sultry afternoon, an exchange unfolded that cut to the core of these questions. After shooting a Facebook Live panel discussion at the Banda Press House, on the challenges of being rural women journalists, Chief Reporter Meera Devi and her colleague Shyamkali Devi decided to take a break in a nearby park. As we settled into the shade, Shyamkali turned to Meera and said, “You said my story’s angle was wrong. I don’t understand how to decide an angle.”

Meera explained—methodically, rigorously—how a story is not simply observed but actively constructed, shaped by the gaze that frames it. Shyamkali listened, absorbing the weight of the insight, and then, after a long pause, responded: “So that’s what an angle is.”

This scene contains within it the most essential inquiry of Writing With Fire: who gets to tell the story? Writing, filming, and documenting are not neutral acts. Documentary filmmakers—no matter how self-aware—are not exempt from the weight of authorship. To acknowledge this is not a flaw but a responsibility. Every act of framing is an act of power, and every documentary, no matter how well-intentioned, participates in that act. In this recursive loop of gaze upon gaze, authorship was neither singular nor fixed but a site of perpetual dialogue, one that forced us, as filmmakers, to question our own place within it.

Once the formalities were inked, access granted, and consent obtained, we had long, searching conversations with the newsroom. One thing was clear: they were exhausted from trying to explain their work. Tired of funders demanding the currency of impact—numbers, data, metrics—when their work could not and should not be measured in such ways. There was a deep desire to be seen and understood in Uttar Pradesh, in India, in the world.

But to be filmed is to be interpreted—framed, structured, edited. The grandness of the news organization’s success or failure was not the spine of our story. Instead, we placed it in the inner worlds of three women and their daily negotiations with power. A working woman heading home from the labor that’s paid to the labor that isn’t. The slow choreography of rickshaws, buses, long walks to report on a school without teachers, a ration shop without ration, a toilet without water.

Meera Devi (L) and Shyamkali Devi (R) in Writing With Fire. Courtesy of Music Box Films

(L to R) Karan Thapliyal, Rintu Thomas, and Suneeta Prajapati BTS. Courtesy of the writer

What choices shape that journey? The sari draped across her shoulder, the way she sits in a bus, the way she enters a chai shop under the gaze of men, the way she positions herself while interviewing a religious hardliner, how she jostles for space in crowded political rallies—each movement a quiet assertion of presence. We sought the story not in spectacle, but in persistence—in the way women move through the world, refusing to disappear.

On our cameras were Sushmit and Karan Thapliyal, men I have known, worked, and argued with in the over 100 short documentaries we’ve made together. Men whose gaze I have come to trust—not because they are free of bias, but because they are willing to wrestle with it. Tall, bearded, city-bred men who needed to find their own meaning of friendship and trust with the women they were filming. In quiet, instinctive choreography, Karan and Sushmit negotiated distance and proximity through a deliberate interplay of close-ups and long shots. No additional lights, no tripods; only hand-held DSLRs to film spaces touched with resilience, tenderness, tension. They arrived with their own stories, vulnerabilities, and humor to exchange with the women, their husbands, male colleagues, fathers, and children in an accessible and equitable way. And they were responded to in equal measure.

Meera and Sushmit would have some of the most profound conversations about each of their married lives, the weight of domesticity, and the slow forfeiting of pieces of oneself. And they developed a friendship deeper than anything Meera and I had shared. Karan, on the other hand, with his easy, unguarded warmth became such good friends with Suneeta that she asked him to stand in as her brother in her wedding ceremony. A small, quiet moment that carried within it a world of meaning.

Can gender, caste, and class dissolve? Only in defiance, and never without cost. These are the tectonic plates of our lives, and it is their fault lines over which we move. But despite them, in defiance of them, can we still reach for something else—something uncalculated, unscripted? A resounding yes.

In 2021, Meera reflected on this alchemy of trust in an interview she was commissioned to conduct with Sushmit and me by this publication, in an interesting role reversal of the interviewer and interviewee. We all understood, perhaps instinctively, that this kind of reversal—a “subject” stepping into the role of interviewer in a commissioned piece—might suggest a more liberated space, but it doesn’t truly shift either the previous dynamics or the power balance. Meera, for her part, reshaped the exchange beyond questions and answers and into a space of shared reckonings and unguarded reflection. She said,

Many people have wondered how we—as Dalit women journalists living in Bundelkhand—collaborated with the Writing With Fire team from Delhi. I don't blame people for being wary. We have been given these preconceived ideas about ourselves, and our castes, that we keep bearing as a burden ... people in Bundelkhand, as in the rest of the world, have very strong religious prejudices. So to see Rintu and Sushmit, each belonging to a different religion, work together and create art together was an inspiration to me. You don’t see that where I live. I was attracted to that way of working and wanted to learn how they did it. It gave me a living example of what happens when people believe in change.

As we filmed Meera and her colleagues, the world outside their newsroom was being rearranged. The BJP came to power in Uttar Pradesh, and led by Yogi Adityanath, it would now demonstrate power not through policy but through spectacle; through digital mobs with factory-fitted rage and a nationalism engineered by technology. And in this shifting landscape, radical youth leader Satyam Tiwari—whom Meera interviews as a reporter—emerged as a cipher and as a clue.

I remember the day we finally got access to film with Satyam—one year of waiting distilled into an afternoon of ritualistic hospitality. Chai, cola, biscuits. An introduction to his sister and mother. And then, moving seamlessly from domestic pleasantries to ideological conviction, he began: “India is a Hindu rashtra, and it is my duty to protect it.”

The rhetoric was familiar, rehearsed. Patriarchy, caste supremacy, religious fundamentalism are articulated with ease, punctuated by theatrics. A sword drawn in a premeditated performance. A self-mythologized spectacle of power. We understood the projection. But we were not looking for a caricature, and so we also traced his journey—unemployed, systemically disadvantaged, swept up as a foot soldier in a larger process.

Meera, drawn to the same intention—trying to understand someone whose worldview opposes your own—became our conduit. While the camera remained on Satyam, our gaze was on her. The way she adjusted her phone camera, steadying it on a jittery monopod, disarmed him with praise, cut in with incisive questions, and finished off with a shared cup of tea. That is the art of negotiation and of dialogue. Writing With Fire exists in this movement—in the deliberate ebb and flow of a story built with nuance.

Nuance, however, is not drama. At least in the world of film financing, nuance is rarely an easy sell. From the start, it was clear that a film about journalists should have a protagonist taking on the system or a newsroom collectively chasing a single high-stakes story. Our pitch about intersectionality did not conform. This tension—between what financiers expected and the story we were interested in telling—would follow us throughout the film’s journey.

A view of the room during the Writing With Fire pitch at the 2017 IDFA Forum. Courtesy of the writer

(L to R) Margje de Koning (then-head of documentaries for EOdocs), Sushmit Ghosh, Rintu Thomas, and Tabitha Jackson (then-director of the documentary program at Sundance Institute) during the IDFA Forum pitch. Courtesy of the writer

In 2017, we pitched the film at DocedgeKolkata, a carefully curated local film pitching forum that offers not only access but also a space to wrestle with one’s work, sharpen its edges, and test its weight against the world. It is a rare space where ambition is tempered by reality, where encouragement exists alongside critique.

After Docedge, we applied for support from outside of India. Over the next few months, support came from IDFA Bertha, Sundance, Chicken & Egg Pictures, and the now-shuttered Tribeca Film Fund—all funds that prioritize nurturing artistic voices. At the same time, there were rejections. Some silent, others curt. Between writing grants and waiting for decisions, we confronted the paradox of our own position simultaneously within and outside the story, insiders by proximity but outsiders in essence. How do we speak in a way that preserves nuance for both Indian and international audiences?

Public and private funding structures for independent feature documentaries in India are quite frugal. The work is long and often solitary. In applying for grants, fellowships, and awards, we were looking not only for financial support but also for community, a shared vocabulary, and the comfort of knowing others were navigating the same uncertainties. And yet, these very spaces of support are built on scarcity. Every application is a competition. The contradiction is hard to ignore: We enter these spaces looking for solidarity but must first prove we are worthier than the others seeking it too.

International financing—grants, co-productions, equity—is a beast. It can offer real possibilities but is enmeshed in quiet inequities and polite extractions. The spectre of colonialism is never far. To navigate these spaces is to learn not only how to negotiate but also how to refuse. To refuse money that comes with editorial control; refuse co-productions that want “Indian stories” but do not want to invest in Indian talent; refuse producers who mistake themselves for shadow directors. To hold our ground was also an act of authorship.

And in this dense crowd, you also find people who see and hear you in the way you’d wish to be seen and heard. Fellow filmmakers, seasoned and fresh, showed up to exchange notes, to help navigate contracts, share learnings. In the end, filmmakers are the best gifts to each other.

Apart from shooting, grant writing, pitching, we were also editing—making sense of a thing still in motion. By 2019, we reached a first assembly of five hours and thirty minutes. We wondered, briefly, if this could be a five-part documentary series. For months, as Sushmit and I edited, we wrestled with the material, shaping it, searching for connections that weren’t immediately visible. And in the strange stillness of the pandemic, we sat with the footage, afraid of oversimplification and of context slipping through the cracks.

Does Suneeta’s easy banter with her father move the story forward, or merely soften its edges? When Meera and Kavita sit together on Republic Day, speaking of women’s freedom over an unusually leisurely lunch, is it a turning point or just another moment swallowed by time? When a small town erupts in the fervour of Ram Navami, colour and swords in tow, is that a climax? Should there even be a climax? When we trace our characters’ courage, does it empower them or leave them more exposed?

How do we frame caste as something lived, visceral, written into breath and bone in ways we will never fully comprehend? Caste is an inheritance, stitched into every Indian life, whether we choose to name it or not.

We held these questions in our hands like river stones—turning them over, feeling their weight, their smoothness, their jagged edges.

The world will now get to know about Khabar Lahariya and its work. There will be a lot of positive impact because of the film… another way of looking at this is that this could also put us at risk, especially from those we are seen questioning in the film.

Meera Devi, Sundance 2021 post-screening Q&A

In 2021, when the film was ready, the world was still holding its quarantined breath. Nevertheless, we drove to Banda to show the film to our protagonists. Our protagonists—who were also leadership bearers in Khabar Lahariya as co-founders, managing editors, and senior reporters—watched the film with us, hid tears, erupted first in unguarded laughter and then applause. As our behind-the-scenes camera rolled, the first to step up was Kavita Bundelkhandi, Khabar Lahariya’s co-founder. She said,

When people watch this film, they will understand how unique and significant our work is. I am proud of that. I am proud of my team. What makes me really happy is that our story has been recorded. Tomorrow, even if I am not around, even if our team is not around, this film will exist to inspire generations to come.

Throughout filming, Kavita often said no to us about what she was willing to share and when the camera had to stop. She had that space, and she exercised the power of refusal. Everyone performs for the camera, but Kavita’s presence was never something she didn’t intend. Which is why her response that day stayed with me. It came from someone who seemed to always actively decide how she would be seen.

This beautiful little video was played during post-screening Q&As around the world, almost as an epilogue to the film.

In January 2021, during the film’s virtual world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, Meera joined us for the post-screening Q&A. In response to a question about the film’s global reach and impact, with characteristic insight, she said,

The world will now get to know about Khabar Lahariya and its work. There will be a lot of positive impact because of the film … another way of looking at this is that this could also put us at risk, especially from those we are seen questioning in the film. They could ask, how are these women allowed to do this. So there are two sides to this.

In retrospect, her words would be prophetic.

***

Understanding that documentary filmmakers are also extractors, Sushmit and I wanted something different for this film’s journey. As filmmakers ourselves, we like to think of ourselves as different—more reflective, more self-aware—but the truth is, we are not exempt from the same uneasy transactions of arriving, taking, and leaving.

From the beginning, we sat with Khabar Lahariya and spent the six years of making and distributing the film in also raising money for them to invest, build, and expand the newsroom in both technology and people. For the work that mattered. So we also discussed the film’s global travels with Khabar Lahariya, not just as participants in the film but as co-architects. How would they walk with the film as it made its way into the world? What did they want from this visibility—from the global gaze it would bring? We sketched out a plan.

Over the first year of its release, Writing With Fire set out on a journey that none of us had imagined—not like this, not at this scale. Between the awards and nominations, the glowing reviews and the momentum that the film was building, one of my favourite memories remains video-calling my parents, holding up a physical copy of the New York Times, telling them that Writing With Fire was a NYT Critics’ Pick. My father, unsure of how big a deal it is, his voice over-encouraging and also curious: “Great. But when is it going to be in Malayala Manorama?”

Meera, Suneeta, and Shyamkali travelled with the film—answering questions at festivals, leading panels, doing masterclasses at Columbia Journalism School. Every press opportunity from the New York Times, the Guardian, BBC, and others, became a platform for KL reporters to share the breadth of their work. New partnerships emerged, in India and beyond.

(L to R) Rintu Thomas, Meera Devi, and Sushmit Ghosh in front of the Writing With Fire poster at IDFA 2021.

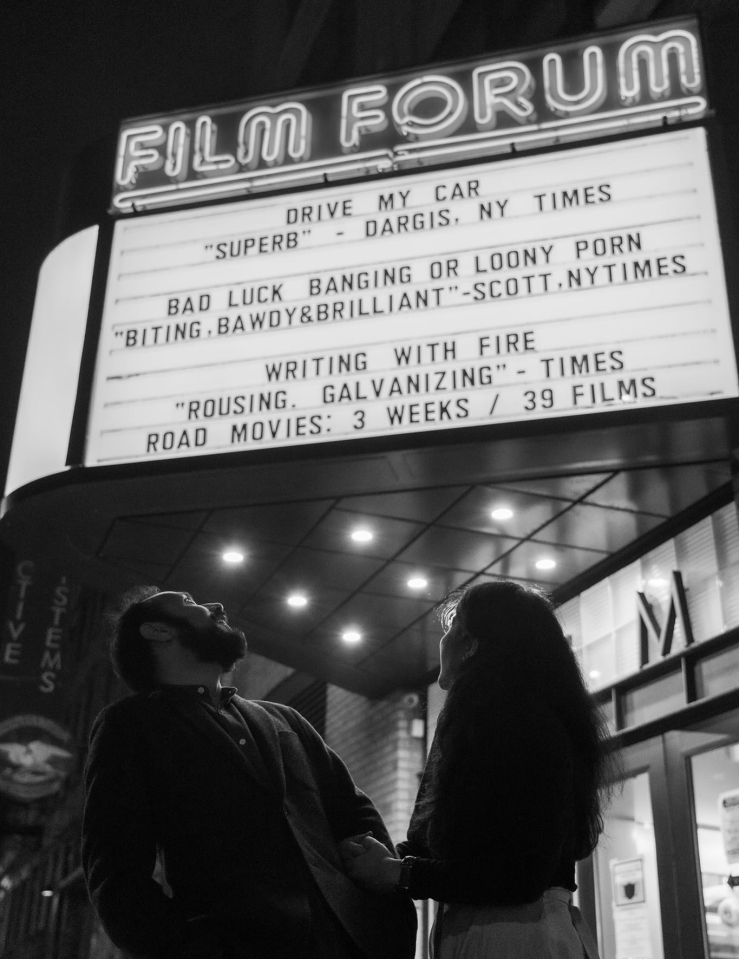

Ghosh (L) and Thomas (R) under the Film Forum marquee during the Writing With Fire theatrical run in NYC. Courtesy of the writer

When the pandemic eased, Meera joined us in Amsterdam at IDFA, experiencing the film with an audience for the first time. She witnessed the rapturous response to both the film and herself. It was beautiful to watch her own the stage, as if it had always been waiting for her. At the Human Rights Film Festival in Berlin, we proposed something that felt truer to the spirit of collaboration—Khabar Lahariya would not just be panelists; they would be co-creators of a three-day conference on “Storytelling for the Common Good,” hosted between Berlin and Banda.

A board member of Khabar Lahariya wrote a thought piece in Youth Ki Awaaz:

I think the greatest thing Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh’s Writing With Fire does is that it makes visible this silent work behind the much-chastised word “empowerment.” May this documentary, which follows three KL journalists through a critical phase of Khabar Lahariya’s evolution, be watched far and wide, and may it continue to do what great documentaries are made to do: bear witness to truths that help us see, for the first time.

Even when the Q&As and panels led to familiar nods and applause for the “brave Indian women,” there was also something more grounded: the tangible support the film’s production had helped provide for the newsroom.

And yet.

The ones behind the camera always walk away with more. Can the benefits ever be truly equal? The glow of recognition is always tilted toward the filmmaker—our careers advance, doors open, prestige grows. But for the participants? Their reality might not have altered in the same tangible, tactile way. The chasm between our worlds gets fully exposed. We believed we had done things differently. But also, was it enough?

In February 2022, Writing With Fire was nominated for an Academy Award.

I call Writing With Fire my sunshine and my crucible. Almost as if scripted by a cinephile with a dark sense of irony, a few weeks after the film’s Oscar nomination, Adityanath won a resounding second term in the UP elections.

And soon after that, with a week to go to the Academy Awards, Khabar Lahariya issued a statement out of the blue, distancing itself from the film with a panoply of arguments. In a separate recorded interview, Kavita Bundelkhandi, the co-founder of Khabar Lahariya, who had recorded the post-screening Q&A video showing her enthusiasm, now described the film’s portrayal of its Dalit protagonists as “bechaaris” (powerless women).

We received this as a gut punch and an interrobang. And then, silence. I read the words again, searching for a reflection of anything that might feel familiar. Hadn’t we built this together? Hadn’t we traveled, spoken, stood side by side with this film for so long, together?

What had changed? Certainly not the film. But the world around it had.

There’s a line from Khabar Lahariya’s statement—“Part stories have a way of distorting the whole sometimes”—which held within it a truth I could not ignore. We had made a film about power, but perhaps we had also stepped into the complex, shifting terrain of power itself. Within Khabar Lahariya, the caste and class contours of leadership had shifted. With the Oscar nomination, new voices with whom we had never interacted stepped in. Who approves and for whom?

Is it the participants who themselves are independent journalists in leadership roles as co-founders, managing editors, senior reporters; the news organization being portrayed that stood behind the film throughout its global journey but is now reshaping itself; or every individual who’s ever been a part of the institution’s management and now demands a voice in its moment of greatest visibility? What are the tenuous threads of power between “protagonists” and “management” that filmmakers must continually navigate? These tangled layers of power, authorship, and identity are reconfigured restlessly as the political landscape shifts beneath them.

Yet I couldn’t reconcile with the most critical question: Why would a newsroom—run by women with undeniable agency—stand behind and participate in the film’s very public, very global journey for well over a year, if this was never truly their story? And why, after all this time, did they choose this moment to step away?

Meera Devi (center) in Writing With Fire. Courtesy of Music Box Films

Suneeta Prajapati (L) reporting in Writing With Fire. Courtesy of Music Box Films

What compelled the women I had come to love, admire, and stand beside in sisterhood to speak of the film in a language that felt suddenly unfamiliar, almost estranged? Can I truly understand the contours of those decisions? I can speculate. But human nature is complex, and some choices defy full understanding.

One particular set of articles shows how this controversy became a freefall into absolutes and pigeon-holing. Journalist and author Yashica Dutt wrote a February 2022 opinion piece in The Atlantic titled, “Writing With Fire Offers a Masterclass in Journalism.” Here, Dutt noted regarding stories about marginalized communities in the global South, that

when such stories are aimed at U.S. audiences, they sometimes take a hackneyed and patronizing approach, turning their characters into heroes who deserve to be celebrated simply for overcoming the odds. Writing With Fire is different. Each scene attests to the journalists’ grit and resilience, as well as their unmistakable excellence and sophisticated skill—without condescension. …And it’s a credit to the dexterous storytelling of the filmmakers Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh, a couple from New Delhi who are not Dalit, that viewers are able to witness that.

Two months later, writing in the Indian publication The Caravan after Khabar Lahariya’s statement, Dutt writes, “The film boxes its subjects into a preconceived idea that might not fully reflect their reality.” Sharing this piece on her social media handles, she notes, “especially when it comes to Dalit subjects, non-Dalit filmmakers must either comply with the narratives we define for ourselves or stay out of it.”

“Part stories” do indeed have a way of distorting the whole sometimes.

After crescendos of emphatic highs, whirlwind success, a storm and crushing lows, Sushmit and I decided to pause. A deliberate moment of silence. To ask ourselves, why do we do this work, both alone and together. Because the thing about telling a story—especially a story that does not belong to you alone—is that you must always return to the reason you chose to tell it in the first place.

I have often thought about whether I would have made different choices if I had known how this would unfold. Would I have tried to change the outcome by framing things differently? Would I have insisted on longer conversations, deeper introspections? Or, if the act of filmmaking itself—no matter how thoughtful, no matter how collaborative—is always, at some level, an act of trespass, would I still choose nonfiction as the language through which I interpret the world?

***

To be seen in a film is to be frozen in time. And perhaps that is the real tussle—not just to be watched, but watched in one way, forever.

Everything you’ve read this far, from the train, the pull of women’s stories, the act of collaboration, is one current of my story. But identity has other currents and undercurrents, ones you don’t always name until much later. “We’re all in process,” says Maya Angelou about the act of becoming.

Growing up in a hyper-Punjabi pocket of West Delhi, I longed to dissolve into its dominant identity. My darker skin made me Madrasi, a word that made me an outsider before I even understood what it meant to belong. So I rebelled against putting coconut oil on my hair and consumed Bollywood songs to perfect my pronunciation of Hindi words. Being told “You don’t look like a South Indian” was the ultimate affirmation. In my 20s, working on commissioned projects with Delhi’s development sector, where power is tightly held by the upper-class, upper-caste elite, I became acutely aware of my class, too.

It was only in my 30s that I began to see beauty in what I had erased. Documentary filmmaking and engaging with the world through a critical lens became a quiet act of reclamation—a way to return to myself, whole in my contradictions.

In the patchwork of my current identity, I am one version with my mother, another among strangers, another alone. Even within each of these exist a procession of multiple selves. The moment the camera intervenes, a choice is made: which version is fixed into permanence? This is the conundrum of documentary filmmaking—to exist within someone else’s arrangement of reality. This is the ethical anxiety of documentary: no matter how expansive its intent, it is always an act of narrowing. To be seen in a film is to be frozen in time. And perhaps that is the real tussle—not just to be watched, but watched in one way, forever.

And yet, I return to something Meera once said in the Documentary magazine interview:

We have been given these preconceived ideas about ourselves and our castes that we keep bearing as a burden. We have to change that, and we can change that when we interact and collaborate with other people. ...Watching Rintu and Sushmit, each belonging to a different religion, work together and create art together, was an inspiration to me.

Stories are messy. Relationships are messy. Filmmaking, especially the kind that seeks to frame truth and courage, is the messiest of all.

As a global industry, we are finally speaking—haltingly, urgently—about participant care. A conversation long overdue, a reckoning with the extractive nature of documentary filmmaking, the ways in which filmmakers have, for decades, turned people into narratives, flattened complexities into consumable arcs, and walked away with accolades while those whose lives formed the raw material of these stories were left to contend with the aftermath. Accountability must be asked of us. But any reckoning that ignores the instability of the world we document is, at best, incomplete. People change. Institutions shift. Perceptions distort. Politics reshape lives. Reality resists coherence, and to ignore this is to miss the point entirely.

***

We emerged from our long pause by bringing Writing With Fire home. In October 2022, the film premiered to packed audiences at the beloved Dharamshala International Film Festival. The premiere was electric and built great momentum as the film moved through the country. All of it curated by its audience—India’s civil society, women’s rights groups, Ambedkarite and anticaste activists who continue to screen it in film festivals, classrooms, journalism schools, villages, newsrooms, museums, biennales, film clubs, and bookshops.

(And yet, before the film could screen in India, it spent nearly a year navigating the opaque machinery of global distribution, where logic still holds that an Indian story must first be validated abroad before it can truly return home. Learnings for next time.)

For decades, in a country where truth-telling has never been easy and where support systems remain scarce, Indian documentary filmmakers have persisted. Our generation inherits that defiance, but we’ve also been able to access flawed, yet vital international financing structures. We’re part of a moment where nonfiction is being reimagined by filmmakers, both seasoned and emerging, in urgent and inventive ways.

In our own work, we have been playfully interrogating the documentary form. How much performance can nonfiction hold before it fractures? When do the porous edges of framing reveal more than they conceal? These questions, stretching the seams of the form and reassembling its conventions, are animating our process. To work in this space—to push, pull, and play with possibilities—is more than a creative pursuit. It is an exciting provocation.

And then there’s always the fundamental question: What does it mean to see? To frame a world, to rub up against its surface, hoping to grasp what lies beyond? Many years ago, on a train journey through the Western Ghats, I watched a little girl press her face against the window, her breath fogging up the glass. She wasn’t just looking, she was tracing the outline of trees with her fingers, following the arc of a bird in flight, the blur of a passing village. Again and again, she wiped the glass clean, as if sharpening the image, as if trying to be sure of what she was seeing.

I think about her often—about the impulse to look, to frame, to understand. The camera, like that train window, offers a vantage point but never the full picture. That is the true labor of filmmaking—to embrace the beautiful mess that is seeing the world.

Editor’s Note, September 6, 2025: The spelling of Nishit Saran’s name was corrected.