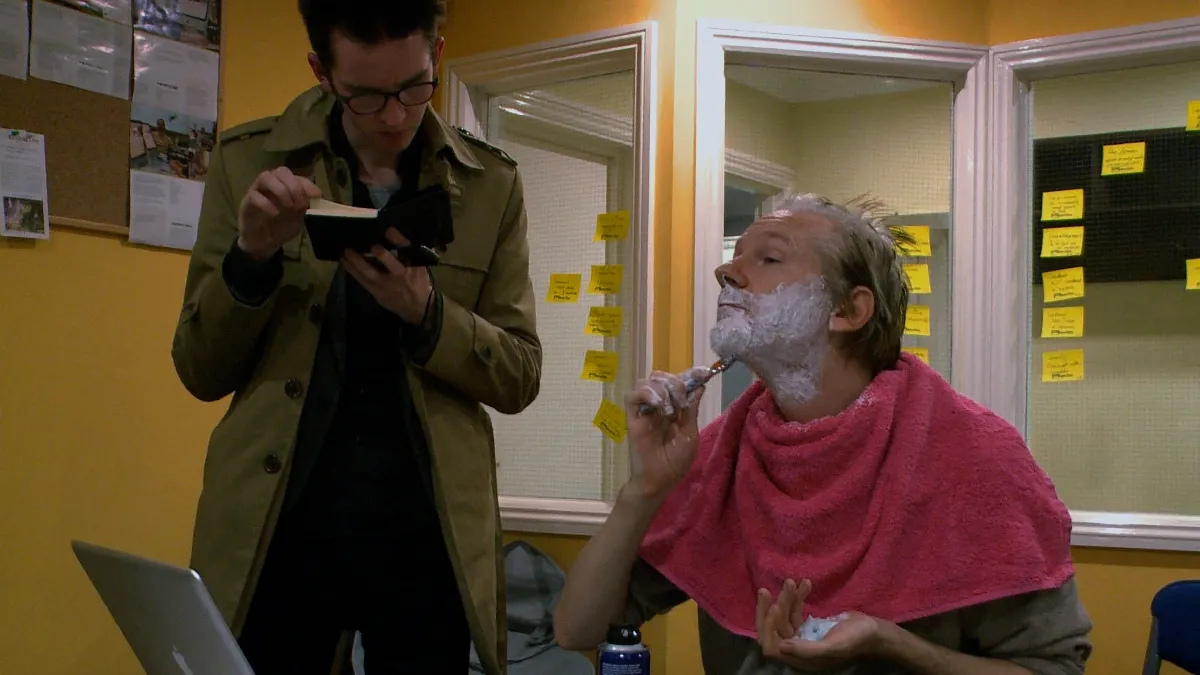

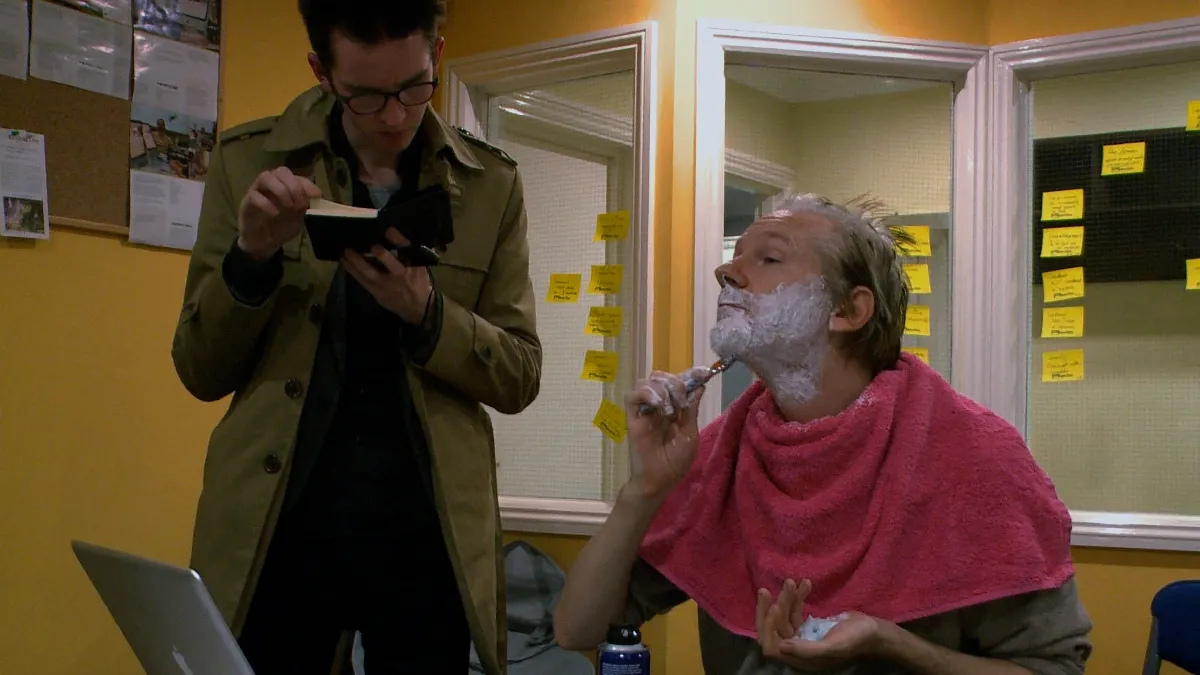

The Six Billion Dollar Man. Courtesy of Sunshine Press Productions Ehf

It is all too easy to overlook nonfiction film at Cannes, where documentary is, if you go by institutional classification, largely a vehicle for chronicling the history of cinema. Every year the Cannes Classics section features, alongside its spellbinding restorations, documentaries about filmmakers, such as this year’s Welcome to Lynchland and My Mom Jayne (i.e., Mansfield), and others on Bo Widerberg and Carlos Diegues. When documentaries somehow make their way into the competition, the selection tends to be director-driven: witness the last two such titles, Wang Bing’s Youth (Spring) and Kaouther Ben Hassania’s Four Daughters in 2023. The tendency continued this year out of competition, with new work by Raoul Peck, Orwell: 2+2=5, and Eugene Jarecki, The Six Billion Dollar Man (previously announced for Sundance 2025 and then withdrawn to incorporate new information).

This year, the most compelling documentaries were found in the parallel festival showcases. The winner of the Œil d’Or (Golden Eye for the best documentary at Cannes) Imago, from Deni Oumar Pitsaev, was in Critics’ Week. Likewise, ACID had the most formally challenging documentary this year at Cannes, Sepideh Farsi’s Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, and it was Directors’ Fortnight that premiered a Ukraine documentary with stunning and often inventive cinematography, Militantropos, by the Tabor Collective. Less than a week before the festival started, a trio of Ukraine documentaries were also added to the lineup for the opening day, including Mstyslav Chernov’s 2,000 Meters to Andriivka, but these first-come-first-served, unbookable screenings felt symbolic (and in fact, reportedly featured only French subtitles for two films, leading to many walkouts).

Festival accounting is boring but necessary when the story of documentary at Cannes is so often told secondhand or in fragments. More people heard about Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk than were able to see it in the opening days of ACID, and for the most horrific of reasons: the killing of the movie’s subject, Gaza photojournalist Fatma Hassona, by the Israeli army. The precision and timing, one day after the film’s selection was announced, suggested a targeted attack against Hassona and several members of her immediate family, according to news reports and the army’s own statement. But as Farsi shows, Hassona’s life in Al-Tuffah, in northeast Gaza, was already in constant danger thanks to the regular bombings. Farsi’s vertical video calls with Hassona are the primary visual connecting us to with her young protagonist, whose circumstances couldn’t be further from those of Farsi, who travels the world with her films and periodically pausing to let her cat in. The two women nurture a bond that is the film’s heartbeat, as Farsi plays the roles of a journalist quizzing her subject but also a friend or aunt showing care through attention from a distance.

Even through the pinhole of a phone’s glitchy portrait, Hassona comes across as a force of nature: a photographer—in between video calls, montages show her portraits of Palestinians amid the ruins—a food-distribution volunteer, a quite shattering poet, an illusion-free and often humorous political observer, a singer, and of course a family member, pulling in a “shy” brother on one call as well as recounting awful losses of life. The film’s title quotes Hassona: every time you walk in the street, you must take your life into your own hands because of the ongoing military attacks. Farsi remarks upon the dazzling smile Hassona flashes, often incongruously at bleak moments in conversation, so much so that it comes to carry not only emotional but almost metaphorical weight though her resilience (the fact that Palestinians have “nothing to lose,” Hassouna says proudly, is their strength). The directorial gamble here is the potential visual and experiential monotony of a phone-centered documentary. But Farsi effectively fashions a chronicle largely from the dispiriting attrition of Hassona’s life in Gaza: fatigue, grief, depression, grave hunger. “I feel like you’re less present,” Farsi tells Hassona at a low point, even as her faraway friend remains front and center.

This candid portrayal is in fact a recognition of Hassona’s humanity, that she cannot be expected to serve always as our heroic correspondent. There’s a subtle and shattering movement at work: the technical limitation of the glitchy phone connection gives way to our concerns about Hassona’s wavering health. Hassona also reflects as an artist on how to process all of this; in a brighter moment, she recommends The Shawshank Redemption to Farsi, for showing how dangerous hope can be. (She also echoes the title of another film when she says that she has no other land except Gaza.) Throughout, Hassona’s bluff manner keeps cutting to the chase: “You have many options to die in Gaza,” she says at one point, and when Farsi asks what the Israeli army uses Apache helicopters for, Hassona replies with an almost bright self-evidence, “To kill us!” What makes Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk an even tougher watch is that it’s now a memorial, and the fact that Hassona feels so indomitable, so alive, says all you need to know about the cynical and cowardly killing before more of the world met her.

Militantropos was another kind of war dispatch from another homefront under attack; the portmanteau title seeks to express how surviving war becomes a part of one’s identity. Directed by Yelizaveta Smith, Alina Gorlova, and Simon Mozgovyi, the 111-minute documentary joins a number of mosaic-style accounts of life in Ukraine and Russia’s attacks, including last year’s Venice selection Songs of Slow Burning Earth from Olha Zhurba and Sergei Loznitsa’s 2024 Cannes entry The Invasion. The cinematographers of Militantropos—Viacheslav Tsvietkov, Khrystyna Lizogub, and Denis Melnyk—push the hi-def images into mysterious and dramatically evocative realms (smoky skies, eerie night photography) while also recording civilian routines (children playing, farming).

The photography just about makes up for the risks of the mosaic approach, which, even with weighty subject matter, can lack a structure to match the power of the images. (There’s one reflexive moment of commentary about war-journalism imagery, when a gaggle of journalists crowd around a camera-ready old woman on a walk.) Criticism that finds visually striking war documentaries somehow problematic misses the point: Militantropos is part of the ongoing, essential self-chronicling by Ukrainian filmmakers, which is unlike so much past war documentary that’s made on behalf of an invaded country.

War forms Imago’s backstory: the director, Pitsaev, hails from a separated Chechen family that had to escape the Russian invasion of Grozny in the 1990s. The rifts and scars from that war persisted as Pitsaev grew up with his mother and did not see his father again until his twenties. The film proper is an ambivalent work of exile and homecoming, showing Pitsaev’s visit to a Chechen enclave in Georgia, where his mother and a cousin have secured land for him to settle down. But the trip really becomes an effort at reunion, because while Pitsaev hangs out a lot with his mother and his bustling cousin (the kind of helpful but potentially overwhelming relative who seems to constantly pop on by), his father’s arrival provides a kind of late-breaking climax.

The usually genial Pitsaev confronts him about his absentee behavior during an extended walk somewhere in the woods, which visually contrasts with the film’s usual pastoral backdrop of rolling hills and verdant countryside. While Pitsaev’s plans to build a house—with a design on stilts that hilariously leaves his family speechless—don’t come to fruition, he moves toward a probably more important emotional goal of some recognition in the eyes of his parents. Many Cannes viewers apparently thought Imago was a work of fiction, maybe because of its quite chill narrative flow, and Pitsaev wouldn’t be unhappy to hear it: during our interview, he took pains to mention that the film had been funded under French financing not for documentary but as “a film for cinema.”

In entirely different circumstances in My Mom Jayne, the director, Mariska Hargitay, also embarks on a filmic journey that leads her to a deeper understanding of a parent. Her mother was the postwar pop culture icon Jayne Mansfield, the star of The Girl Can’t Help It (1956) and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957), who was glibly dismissed as a less serious also-ran to Marilyn Monroe. The mode here is partly the behind-the-scenes Hollywood history doc, but, per the title, via Hargitay’s personal, sympathetic voice. Between her on-and-off-screen narration, interviews with family, and access to private photos and other materials, Hargitay underlines the gap between the public image and the polyglot, violin-playing reality of Mansfield. The film outlines the highlights of Mansfield’s life, from her happy marriage to and family with a Hungarian bodybuilder, professional pressures, subsequent divorce and remarriage, and climaxing, like an awful soap-opera twist, in her death in a crash, which her children mercifully survived. Hargitay delves into her own late-in-life revelation (not specific to this documentary) that she was the product of Mansfield’s affair with Nelson Sardelli, an Italian Vegas singer here brought before the camera for a tearful reunion.

My Mom Jayne might trace a well-trod, at times sentimental path through the ravages of stardom—a familiarity which offers its own condemnation of an industry—but Hargitay crafts a loving primer, and it’s meaningful for her to be doing so about a star who was such a plaything of pop fantasy, as shown in piggishly chauvinist talk show clips. Also tremendously poignant, and not quite elaborated as such, is the study in contrast that Hargitay’s own award-winning career provides: a marvel of steady determination as a TV star playing the longest-running prime-time drama character, on Law & Order: SVU, solving crimes against women for 20-plus years.

A very different biographical investigation unfolds in Orwell: 2+2=5, in which Peck reflects upon the essential 20th-century thinker who has been distilled into an epithet meant to call out a totalitarian scenario and somehow magically inspire everyone to come to their senses and stop it. The challenge for Peck is to reintroduce us to Orwell’s thought with something of the same éclat as he indelibly interpreted James Baldwin for new audiences. With characteristic curiosity he digs into Orwell’s journals and letters to paint a picture of the boy born under British imperialism who became a lucid anatomist of the dystopias waiting in the wings post–World War II.

Peck’s two-hour film tacks between Orwell (born Eric Blair) gloomily writing 1984 in Scotland as he grows more and more ill from tuberculosis (with letters and journals read out in Damian Lewis’s voiceover); clips from film adaptations of Orwell and other works such as Loach’s Land of Freedom; and a bubbling stew of parallels to our Trump-Putin era that’s brought to a somewhat chaotically raging boil. The trouble is the film’s tendency (in which it is not alone these days) to pile on the evidence of encroaching doom and doublespeak that already drown us all from day to day. A new Peck always finds me eager to think through history alongside him, but one wonders if a pared-down clarity might have been more effective here, perhaps much as Orwell achieves in his parable-slim Animal Farm.

Finally, Eugene Jarecki’s The Six Billion Dollar Man gives a walk-through of the rise, accomplishments, and near-vanishing of Julian Assange, who exposed U.S. military malfeasances through the anonymous submission platform Wikileaks, initially as a rogue outfit and then in partnership with legacy news organizations. Winner of the second-place L’Œil d’Or jury prize, this dense timeline documentary (apparently made by Jarecki while he himself lived in refuge in Germany) is a bit exhausting as it recapitulates recent history. Until, that is, it reaches Assange’s bizarre extended asylum in the Ecuadorean embassy in London, where he sought to avoid extradition on criminal charges.

Here, the documentary rack-focuses on the queasy reality of a man many nations probably saw as a grave inconvenience to statecraft. Even inside the Ecuadorean embassy, Assange was subject to total surveillance and perhaps even poisoning, with the film drawing links from the embassy’s security detail to a Trump ally; the title refers to an IMF loan to Ecuador that the Trump administration allegedly used to induce Assange’s expulsion. Though replete with interviews with key figures—including a creepy Icelandic hacker who aided Assange, and a beardy pontificating Edward Snowden—the documentary has trouble balancing its investigative angles with its treatment of Assange as an avatar of freedom. The Six Billion Dollar Man is at once ever-topical and also moored to past debates. The film ends up demonstrating the ongoing challenges of communicating (not to mention coping with) successive eras and instances of historical injustice, as an ever-more-violently shifting present beats down the door.

Nicolas Rapold is the host of the podcast The Last Thing I Saw, a frequent contributor to numerous publications, and former editor-in-chief of Film Comment. He is editing a book of interviews with Frederick Wiseman.