“How War Becomes Part of the Human”: Alina Gorlova, Yelizaveta Smith, and Simon Mozgovyi on their Cannes-Premiering ‘Militantropos’

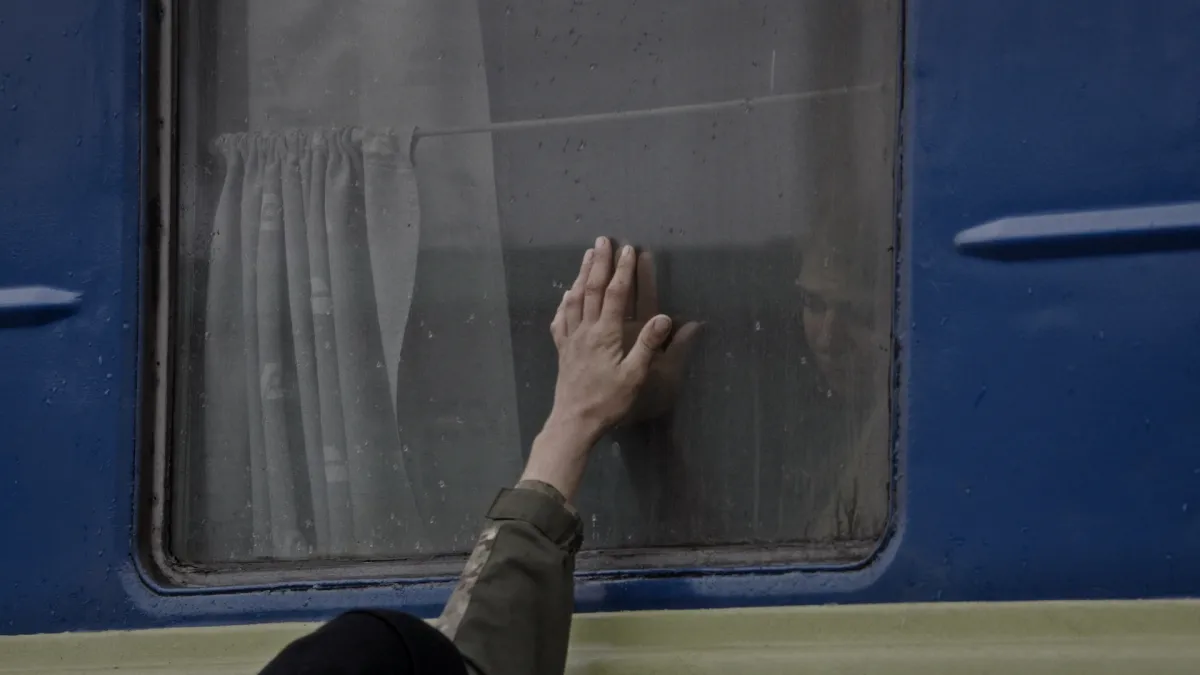

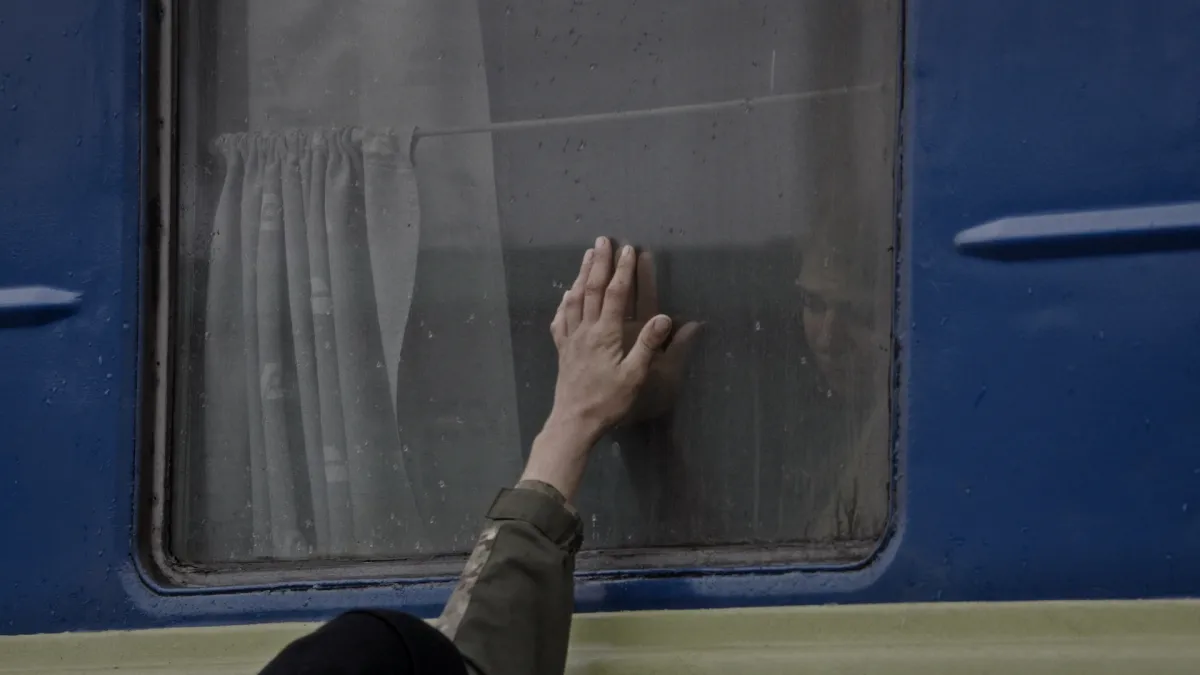

Courtesy of the filmmakers

Alina Gorlova, Yelizaveta Smith, and Simon Mozgovyi’s riveting Militantropos, its title a mashup of “milit" (soldier in Latin) and “antropos” (human in Greek), is a striking verité look at how people don’t just fight wars but become “absorbed into war.” Indeed, through a series of meticulously framed images, along with a visceral sound design, we’re taken on a swift-moving trip through the surreality of today’s Ukraine—from the training of everyday citizens in lethal weaponry, to wandering cows on a decimated farm. But also children picnicking in a field, and farmers meticulously tending to their crops, bombs in the distance be damned. If there’s one thing the “militantropos” can count on, it’s that amidst ever-present death, the cycle of life carries on.

A week prior to the film’s Directors’ Fortnight premiere, Documentary caught up with the co-directing trio, all members of the prolific indie production company Tabor (its CEO, producer Eugene Rachkovsky, also chimed in briefly). Tabor was founded by a group of Ukrainian filmmakers and artists in 2013, the year before Russia annexed Crimea and set the path to the ongoing war. This interview has been edited.

DOCUMENTARY: How did the idea for Militantropos originate? And since this is the first film in a triptych, I’m also curious to hear how you envision the second and third parts. Will they likewise focus on “the powerful impact of war on personal behavior,” or do you plan to address other themes?

ALINA GORLOVA: Our co-scriptwriter Maksym Nakonechnyi invented the neologism “Militantropos.” After six months of shooting, which began at the very start of the full-scale invasion, we started to rewatch all the footage we had. It was during this process that we realized our material had strong potential, so we decided to conceptualize it.

Through our ongoing research, filming, and previous experience working on films about war, we recognized that we were dealing with something fundamental: the nature of war itself. This led us to structure the project as a triptych, divided into three thematic branches: how war transforms the human being; how war changes the perception of death; how war influences space and time. The first film, Militantropos, focuses on the transformation of the human during war—how war becomes part of the human, and how the human becomes part of war.

D: How exactly did you split up filmmaking duties? Were you filming together or separately?

SIMON MOZGOVYI: At the start of the Russian invasion, shooting was our inner way of life, a reaction to all the hostilities we encountered.

Our desire was to investigate the heart of conflict. We believed that an individual experience would not be as strong and profound, so we decided to create a collaborative project. We had numerous directors and DPs working in separate groups, and we were constantly exchanging roles and teams, yet all of our footage flowed in the same direction. In total, we shot for about two and a half years.

There was no need for all the directors to be permanently in the editing room. One could go filming while the other continued editing. We had horizontal connections on our film, no hierarchy; only a deep understanding of each other, which developed over the years of friendship and working together.

D: How did you develop the film’s aesthetic? The overwhelming scale of the war is captured in such precise vérité images, while the sound design acts almost as an invisible force.

YELIZAVETA SMITH: Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, we’ve been having ongoing discussions in the collective about the experience we are going through—feelings and the form in which we’ve decided to shoot.

The choice to film observationally with a static camera just came naturally. It allowed us to frame the reality around us while keeping our distance. I’d also like to highlight the incredible sensitivity and talent of our co-authors, DPs Viacheslav Tsvietkov, Khrystyna Lizohub, and Denys Melnyk. Their subtle sense of space and framing matched the directors’ intentions.

We were all editing and shooting at the same time. While working on the film’s dramaturgy, we realized that we wanted to get closer to a human, one who had already transformed into Militantropos. That’s why we consciously changed our approach throughout the film, as if the camera were also transforming and getting closer to the human faces, breaths, and emotions.

We were also working on the sound from the very beginning of the editing. Sound is a crucial element in times of war, as it is listening that informs the brain of the danger of an approaching attack. During the filming, the team recorded absolutely unique sounds—the forest and artillery battles at the frontline, as well as nature, insects, and birds that continue to live and resound in the space.

We collaborated with the very talented sound supervisor Mykhailo Zakutskyi and composer and sound designer Peter Kutin, creating the sound body of the film together in Vienna. (Peter’s music was actually written partly from the sounds the team recorded throughout the war.) We all wanted the soundtrack to be a part of the dramaturgy, but not to stand out from the visuals; on the contrary, we wished to deepen the viewer’s experience.

D: Could you talk a bit about your production company Tabor? Was it started in response to the tumultuous events at the time? How has its mission evolved?

EUGENE RACHKOVSKY: Tabor is more than just a production company, it’s a collective of like-minded filmmakers and authors who came of age alongside Ukraine’s independence.

Our mission has always been rooted in reflecting the modern history of our country through personal and collective stories. Founded in 2013, Tabor emerged shortly before a year that was deeply transformative for all of us, both personally and collectively. The Revolution of Dignity was a defining moment—the collective was not only in Independence Square protesting together, but also documenting what was happening. This naturally evolved into our first steps as filmmakers. Then when the Russian-Ukrainian war began in 2014, many of us went to Eastern Ukraine to volunteer and to film. These experiences shaped the foundation of Tabor.

Over time, the company has become a place for experimental visual storytelling centered on socially important topics. Films like This Rain Will Never Stop [dir. Alina Gorlova, 2020], School Number 3 [dirs. Georg Genoux and Yelizaveta Smith, 2016], No Obvious Signs [dir. Alina Gorlova, 2018], and Butterfly Vision [dir. Maksym Nakonechnyi, 2022] are all part of that journey—attempts to explore and share the complexity of life during war. Militantropos is a continuation of this process, and of our desire to document, reflect, and create from within the lived experience of Ukraine.

D: Admittedly, Ukrainian nonfiction filmmaking hadn’t really been on my radar until 2018, when I attended Docudays UA and was blown away by Alina’s award-winning No Obvious Signs and also by her decision to put her prize money towards establishing a veterans’ rehab organization specifically for women. This reminded me that so many Ukrainian documentarians have long been dedicated to the war effort, going all the way back to 2014. Do you ever dare to imagine a time when you’ll be able to tell other stories? What would that look like for you, having been personally and artistically shaped by the Russian invasion?

AG: Our collective was indeed shaped by the events we lived through. We’re all in our thirties—more or less the same age as independent Ukraine. We were born when the Soviet Union collapsed, and we grew up in Ukraine, with its borders feeling natural to us.

Then came the Revolution of Dignity and the war that followed. These events played a defining role in who we are today. That was the moment when our collective began working in documentary filmmaking and started to develop our cinematic language. So yes, we were very much shaped by these experiences.

I believe the Revolution of Dignity gave a strong impulse to Ukrainian documentary cinema just, unfortunately, as the full-scale invasion later did. But I don’t think it’s only about the topic of war. It’s about the transformation you go through as a person. This is a coming-of-age story—our story, the story of our generation, and the story of our collective. We grew up and were formed through these historical moments. In a way, we were lucky. I do believe that. I respect my experience, and I wouldn’t want to live a different life.

We need to understand the context and history behind all of this. The Soviet Union rewrote history, erased identities, and replaced them with its own narratives. We grew up at the same time Ukrainian society was beginning to dismantle these Soviet fakes—uncovering the real history, reclaiming the truth—the anti-colonial story. It’s a long and complex process, not something that can be completed in just a few years.

Rediscovering Ukrainian artistic traditions was also part of this larger process. It’s crucial to know who you truly are, not who an empire wants you to believe you are. That’s exactly why Russia opposes this process. They want to reverse it, to drag everything back into the past.

As for whether we want, and are able, to make films that aren’t about war, yes, absolutely. Many of us write and have written scripts for fiction films in which war is not the central theme, or not present at all.

Lauren Wissot is a film critic and journalist, filmmaker and programmer, and a contributing editor at both Filmmaker magazine and Documentary magazine. She also writes regularly for Modern Times Review (The European Documentary Magazine) and has served as the director of programming at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival and the Santa Fe Independent Film Festival.