Winner of the top prize at IDFA 2025, A Fox Under a Pink Moon follows Soraya Akhalaghi, a teenage Afghan artist who is a dazzlingly talented sculptor and painter. But as we quickly see—through filming done by Soraya herself, in remote collaboration with the Iranian director Mehrdad Oskouei—she is also repeatedly attempting to emigrate with the help of smugglers, and accompanied by her brutally abusive husband. Any one of these elements could have been the basis of a single documentary, but Oskouei and Soraya (credited as a co-director) create a vibrant record of her experience that’s true to its mingling of banal, awful, and wondrous.

Joining a many-branched lineage of migrant documentaries, this particular journey feels catalyzed by Soraya’s art and sly verve. In the film, we watch her working as a cleaner in a Tehran apartment building, stealing moments to paint swirling colorful canvases with clown and fox motifs, or carve grey goblin-like grotesques. Framing herself in often remarkably clean compositions, she’s not presented as a vessel for our sympathy. Nor is the film a facile picture of art-as-uplift. She’s an agent of her own survival and freedom, though her path is not a straightforward one over the film’s neatly compressed several years.

At IDFA (where Oskouei has been a fixture for over 20 years), I spoke with Oskouei and Soraya, with contributions from producer Siavash Jamali, before A Fox Under a Pink Moon won Best Film in the International Competition. The tight-knit bond between them—including their translator, who turned out to be Oskouei’s daughter Alma—was apparent, with Soraya and Alma alternately lending each other a comforting hand during answers. This interview has been edited.

DOCUMENTARY: How did you decide to start this?

MEHRDAD OSKOUEI: I wanted to make a film about an outsider artist, a sculptor in Iran. He had a workshop in a basement. In his workshop, there were two girls, like interns, who would sculpt stuff for him. One day, when I was bringing some clients to him, I saw a really introverted child who was doing stuff at the back of the workshop. And she came to me and said, “What do you think about what I do?” I couldn’t believe her because the work was incredible. So I said, “Oh, yeah, great, it’s really nice.” And she said, “Oh, you don't believe that I am sculpting this stuff.” So she sat down and started sculpting something, then showed it to me. I realized that I was talking with a little genius. I looked into her eyes, and there was this pride, this strength, this independence. At that moment, I said to myself, okay, she’s the one that I’ll be making a film about.

We kept on talking. She told me that she was married to an Afghan boy at the age of 14. I figured out that when she was 7, her mother left Iran after the death of her father, leaving her with her uncle. The wife of this uncle was really brutal with her. We were continuing this process [of talking] until my film, Starless Dreams [2016] was released in Japan. Then I received a message from her: “Where are you, Uncle Mehrdad? I’ve been calling you.” She told me that the husband had told her the day before to bring everything you want with you, we’re going to have a game [slang for emigration attempt] and go out of Iran. And that was the beginning of filming the journey to Turkey.

SIAVASH JAMALI: When the film starts in 2019, Soraya says, “It’s the 19th of November, I am in Turkey.” Exactly on the 20th of November, we had the opening film here [at IDFA], Sunless Shadows.

D: How did the planning work for making the film? Did you send each other videos at regular points?

MO: From the day I decide to make a film, I prepare my crew. I immediately contacted my executive producer, Siavash, and then my editor and my composer, so I have my crew around. And I told the people in charge of the postproduction that I am working with a mobile phone. How do we do this technically, how do we manage the content? Everything that Soraya would send me, I would send to this person in charge of the archives with the name, date, and an explanation with what’s going on in the scene. And with Soraya herself, we had more than 400 sessions of work. It was a huge amount of work.

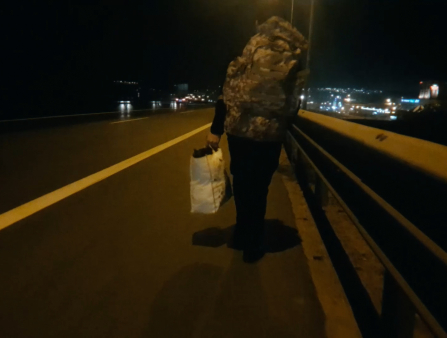

During the day, Soraya had her daily life and her obligations in other houses, and her husband. When she called me, it was mainly in the night when she was on the roof between 11 and 12 at night, after the husband would go to bed. We would laugh, we would cry—she’s introverted but she’s also really funny. We would go through the history of art in these sessions—photographers, painters, sculptors, just watching their work. She would, for example, say, “Oh Uncle Mehrdad, I want to shoot this scene as Sebastião Salgado shoots his photographs.” Or: “Look at these paintings, I’m inspired by Frida Kahlo and Marc Chagall.” She would also go through traditional references: she would use patterns that Afghan women use in the cloth they put on their beds, and she would have photos of them and put them in her paintings. And I asked her to do more paintings, and I bought her a great set of colored pencils. [Soraya beams at this.]

D: Soraya, did this process at the end of the night feel a bit like keeping a journal or a notebook?

SORAYA AKHALAGHI: For me, it was not mainly about the film. At that time, I had really nobody. Nobody would believe in me, and everyone around me was really brutal and trying to tell me that I couldn’t do anything in life. Then there is Uncle Merhdad, who appears and tells me, “Oh, your drawings are nice,” and I send him my drawings. “This is great, I want to see more!” And it was the same thing with the shots. When I would send some shots, he was like, “Wow, this is great, now do more,” show me this, show me that. For me, I wanted to feel that encouragement in my life that he would give me.

D: It also feels like the camera can be helpful when you’re doing something hard, to give you a distance from what’s happening, like when you are filming on the smugglers’ boat.

SA: It was really a hard experience because I was among these smugglers. That time, we went through this path that was extremely dangerous—the most dangerous of games. I could pass the borders, or I could die. There’s no going back. As I would just think about death, I was just thinking, okay, I could die, so I would just use the camera and shoot everything, because at the end, there was just death.

D: The film also includes scenes of domestic violence and the aftermath. How did you talk about showing that in the film?

MO: The violence that Soraya went through was multiple times harder and harsher than what you saw in the film. I had a daughter who was roughly the same age, and I couldn’t bear it. [Translator adds: “I’m his daughter.”]

Sometimes the husband of Soraya would call say, “Okay, Uncle Mehrdad, I hit her really bad, we’re heading to the hospital, but we have no money so can you just come and pay for the doctors?” Once the husband called me and said, “Is Soraya with you?” I said, “No, why?” He said, “She went to see her family, and she’s really late.” And he really, really beat her hard. This is the scene with the huge bruise on her arms. And I went there and I saw Soraya in the corner of the room, like a small bird in the rain, just weeping. I was shattered because I couldn't go give her a hug because of the circumstances and religious beliefs of the husband. I couldn’t do anything, so I was really broken inside.

That day, I called my crew, everyone came, it was at night, and I said, “This can’t go on, we will get a lawyer and get a divorce.” Then a day later, the husband said, “Oh, no, you’re really clever because you want to help her go across the border, and my hope, my single hope in life, is to go and cross the border with her. Because without her, I can never do it. So I won’t get a divorce because I want to cross the country too.”

D: Soraya, how did it feel for you to have those experiences in the film?

SA: The memories came back. When I was seeing it for the first time, it was really painful, but when I saw the end and what I went through and what I succeeded in this journey, it helped me recover. The ending was a happy ending.

MO: When she was beaten, she couldn’t just shoot the scenes, but she had recorded all the sounds of what was going on. For me and Siavash, the goal was not to make the film. We wanted for Soraya to survive.

SA: At the very beginning, I would shoot these scenes when I was beaten. My ex-husband [the end of the film reveals that Soraya and her former husband are now divorced] was not paying attention to the camera that was elsewhere in the room.

But as the film went on, he became aware of it and that it might be something serious, so he would delete everything that I’d shot, because I had these scenes where I was talking to the camera about what happened and how I was feeling at that moment. I really liked these scenes, and I wanted to send them to the crew, but he would just go through everything and delete it. When I saw this situation, I used to just hide my phone recording behind a pillow. So [that’s why] we would also have just the voice.

MO: This is the first time that she told me that this was the process—today!

D: What was the significance of the fox and clown images for you?

SA: For me, I was like the clown. Because I always had to have the smile on and show everyone that I was happy, satisfied. I couldn’t tell them that nothing was okay and I couldn’t express my feelings. In Iran and Afghanistan, there are not enough rights for girls and women. In order for me to be able to divorce someone over domestic violence, I had to go to a hospital for domestic violence three times. I went there once, and the second time, my ex-husband knew that I was going there, so he would just lock me in. He would bring creams and stuff to put on in order for it to get better. When he saw that it was better, he said, “Okay, you can go to work.” In this period of time, I was just locked in, I couldn't go anywhere, I couldn’t do anything. I just had to go out and pretend that nothing was going on and everything was fine. That’s why I’m like the clown.

I really love the fox. The fox doesn’t like humans. It just goes away from humans. It's clever and kind and can really care for itself. [In English:] And beautiful.

D: Have you ever seen a fox in the wild?

SA: Yes, in Berlin. I saw it four times.

D: Where did the idea for the part-animated shot of Soraya sitting with a fox under the moon come from?

SIAVASH JAMALI: Mehrdad added it last year, when he was working on animation. We were talking about merging animation with real scenes. Before that, we had just [separate] animations. At first, we just added the fox, and Mehrdad said we needed something else, so we added that pink moon. It came from the title of the film, which came first.

SORAYA AKHALAGHI: This was shot on the roof, which was my safe space. On this roof, there was a smaller roof with a small ladder for checking the A/Cs. And I would go up on the top of this smaller roof on the roof because I had this panoramic view, and also could see the ex-husband coming. When I saw him coming, I would just delete [all the videos] into the recycle bin, so he wouldn’t go through the gallery. He didn’t know about the recycle bin thing, that you can just restore it afterward. So I would show him the phone, and then I would just restore everything on the phone and send it.

MO: I didn’t know that. You surprised me, my friend!

D: I have a question about time. It’s so beautiful, in a film that tells the story of so many years, that you feel the time passing, but you also don’t, in a way. Could you talk about how you create that sense of the time?

MO: After my tetralogy about [imprisoned] youths, I had this idea of filming in time-lapse. The notion of time in documentary was really occupying a huge space in my mind—the real time and the philosophical concept of time. I am 56 years old. And when we started filming, I was about 48 or 49. It was like I had passed by this whole idea of making films, and being seen in the industry was behind me. The real thing is that Siavash and I would make films to soothe ourselves. We keep finding creativity through decreasing [the materials in a film]. We erase everything that we can, erase the sound when it’s possible, erase the number of images that people can see, in order to lighten up the whole thing for viewers to be able to communicate with what’s going on the screen. We can consider our films as an incomplete series of shots that are completed with what each and every viewer is adding emotionally to them, mind and heart.

D: Soraya, who are your favorite artists or movies?

SA: I have this habit of not liking or following people that are super-famous. Because I tell myself that, yeah, this person is famous, super followed by everyone, but that person’s work is also great, so why not this person but that person? This person also can be superfamous. I don’t watch so many movies. My favorite artist in visual arts is Marc Chagall.

Here’s my favorite music that I love and listen to all the time. [Plays for me on phone.] “Deadman on Vacation” by April Rain. Uncle Mehrdad used to send me this kind of music. He would ask me to listen to it with my eyes closed, and when it was finished, to open my eyes and shoot the film with how I was under the inspiration of the sounds that I was hearing. And from that moment on, this became my favorite music.