Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina Celebrates 40 Years of Amplifying the Voices of Hawai'i

“Hawai‘i is the extinction capital and endangered species capitol of the world,” declares Kealoha Pisciotta, a Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) traditional knowledge-keeper and cultural practitioner, in the 2005 documentary Mauna Kea—Temple Under Siege, “We cannot support de-creation…It is against the law of the universe and creator to eliminate a species.”

In 2020, this award-winning documentary by Joan Lander and the late, beloved Puhipau, was added to the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress. They enjoyed a lifelong professional and loving partnership, forming Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina (“The Eyes of the Land”), an independent video production company that focuses on educating people in Hawai‘i and across the globe on the issues impacting the land and people of Hawai‘i and the Pacific. They had produced around 100 programs by the time of Puhipau’s passing in 2016. To date, Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina is one of Hawai‘i’s most groundbreaking and widely recognized documentary production teams. In addition to their prolific coverage on the desecration of the sacred mountain Mauna Kea, the company has covered a myriad of other matters over the course of four decades. Native Hawaiian organization Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea, which commemorates Sovereignty Restoration Day, demonstrated the great impact of Puhipau and Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina, when they honored him in 2019.

Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina’s documentaries have focused on the devastating impacts of US militarization in Hawai‘i and Oceania; the environmental effects of geothermal expansion; the violations of excavating burial grounds; resistance to evictions across the islands; and the perpetuation of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the face of prolonged illegal US occupation. They have also produced videos on cultural knowledge and ingenuity, and their work has earned the acclaim of such prominent entities as the Hawai‘i House of Representatives, the Hawai‘i Film Office, Pacific Islanders in Communications, Hawai‘i People’s Fund and Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation. In 2017, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs distinguished Puhipau among “Nā Mamo Makamae o ka Po‘e Hawai‘i” (Living Treasures of the Hawaiian People). Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina was most recently recognized at the 2022 Hawai‘i Triennial, a multi-site exhibition of contemporary art from Hawai‘i, Asia-Pacific, and beyond.

Abraham “Puhipau” Ahmad was born in 1937 and raised on the island of Hawai‘i to Kānaka Maoli and Palestinian parents. After graduating from Kamehameha Schools, which is an institution dedicated to educating Kānaka Maoli students, Puhipau spent years traveling the world. He returned to Hawai‘i in 1970 and lived in the urban fishing community of Sand Island, on O‘ahu. He adopted the name Puhipau in the early 1980’s after seeing it on his family tree. He explained that “puhi pau means blown away, completely burned. Puhi pau ʻia nā mea huna: ‘all the secrets were revealed.’”

Joan Lander was born in Maryland and raised in Ohio and Indiana. After attending college in St. Louis, she joined Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) and was stationed in Colorado. She visited Hawai‘i for a week and fell in love with the islands. She applied for a job in radio and was hired by a station on Hawai‘i Island in 1970. Her passion for justice, involvement in the anti-Vietnam War movement, and experience doing community organizing in Colorado led her to join the environmental organization Life of the Land. She soon discovered that Hawai‘i was not the perfect paradise; it harbored severe issues that deserved immediate attention.

In the 1970s, when small-format video was introduced and cable television companies were setting up their businesses, Lander began producing with a group called Videololo, where she produced educational films for the Department of Education until 1980 when a large group of predominantly Kānaka Maoli was forcefully evicted from Sand Island for allegedly squatting on public lands. Puhipau and others were arrested for not leaving. Their lawyer provided the defendants with the book Hawaii’s Story by Hawaii’s Queen, by Queen Liliʻuokalani, the last reigning monarch of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i. This propelled Puhipau to delve deeper into the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Meanwhile, Jerry Rochford and Victoria Keith began producing a documentary on the eviction. Lander helped edit the footage, and The Sand Island Story aired on PBS as a part of a national series called Matters of Life and Death. Through this project, Lander was introduced to Puhipau, who narrated the documentary and played an important role as the liaison between the producers and the people of Sand Island. From that experience, he realized that video could be the perfect means to share with his people the history and knowledge he had learned. Lander was always interested in producing films on Hawaiian issues, but was also hyper-aware of her identity as a non-Kānaka Maoli woman from the continental United States, and felt that she was “too much of a malihini [newcomer or stranger].” Puhipau suggested they make films together—opening the door to a lifelong mission of utilizing storytelling to inspire a just and transformative future for Hawai‘i, and forming Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina.

Taylour Chang, a Kānaka Maoli filmmaker and Director of Public Programs and Community Engagement at the Bishop Museum, affirms the deep influence of Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina on her as a filmmaker. “I think they set for us a very beautiful example of what partnerships can look like—how that can generate so much creativity and be sort of external expressions. It was so beneficial to the community.”

Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina began by producing Hawaiian cultural documentaries for the Department of Education, as well as covering evictions, land and water rights, and other pertinent issues facing the Kānaka Maoli community. A pinnacle moment arrived in 1993, at the fore of the 100-year anniversary of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, when they secured support from the federally funded Independent Television Service to produce a feature documentary on the history of the overthrow. Lander explains that their grant caused a commotion in Congress as lawmakers complained of taxpayer dollars going to produce Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina’s film, Act of War - The Overthrow of the Hawaiian Nation.

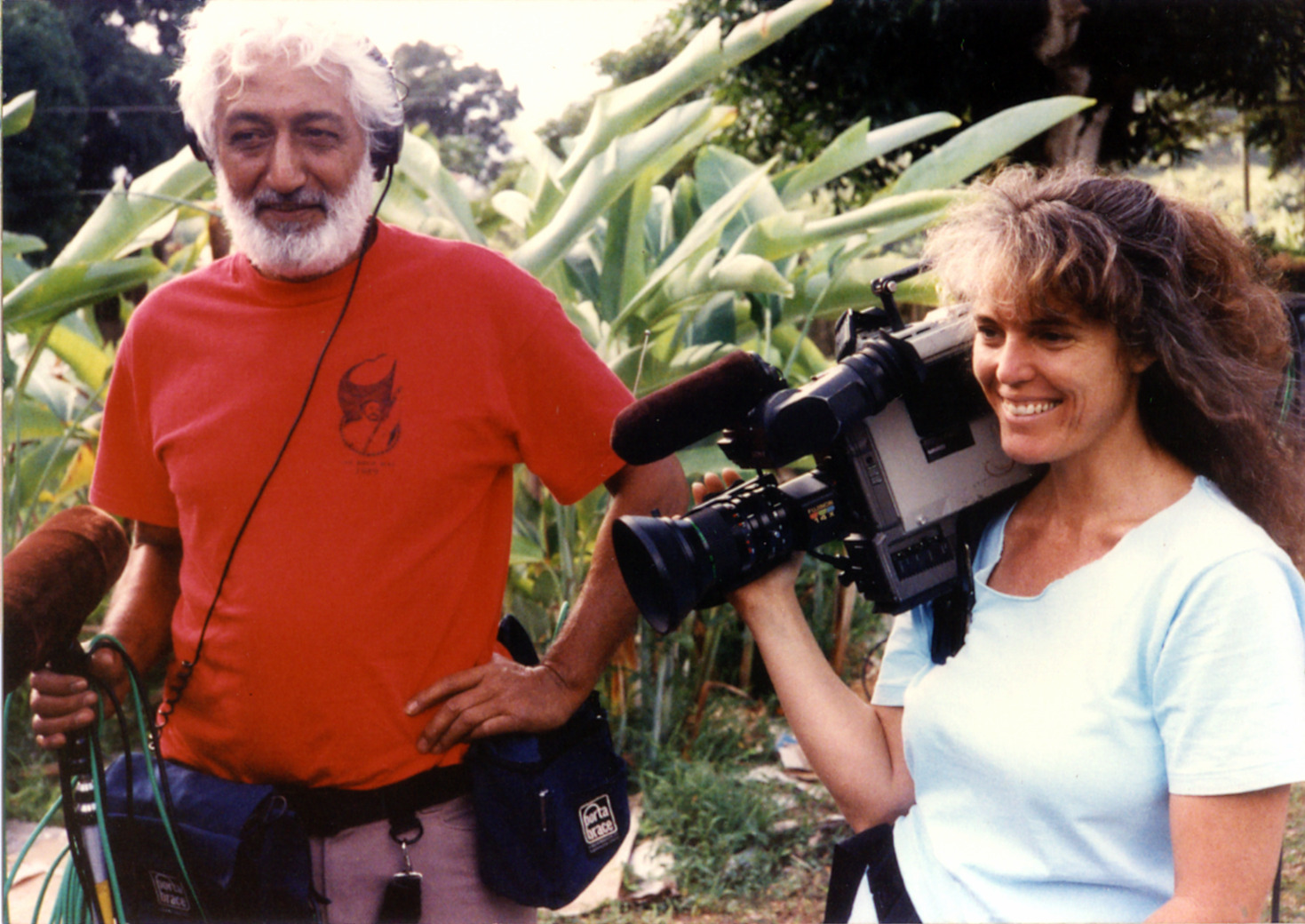

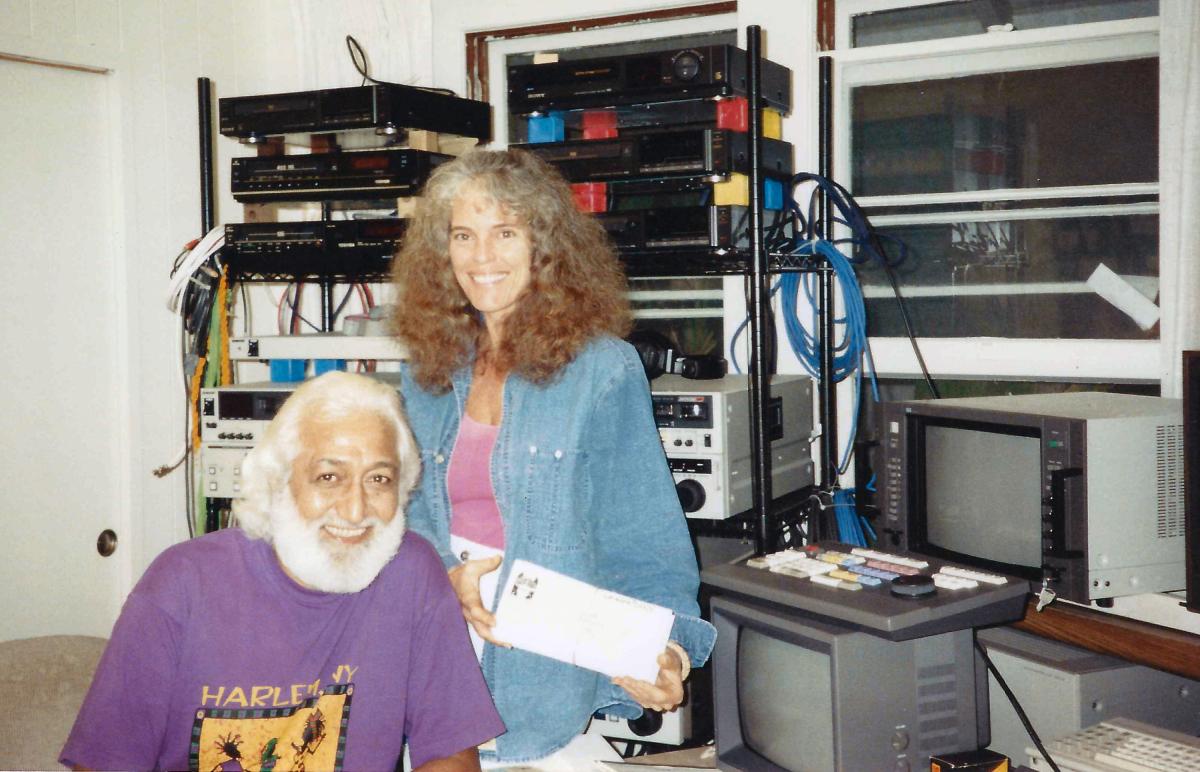

Lander and Puhipau co-produced all of their productions, with Lander behind the camera and Puhipau handling sound most of the time. They edited all of their films together.

Lander recognized that Puhipau needed to be the face of Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina. “He would be the one out front, which was fine with me because it's his land. It's his culture. It's his people. Who wants to see another haole [foreigner, often implying Caucasian] talking for the Hawaiian people?”

She is also highly aware of the disparaging behaviors of many filmmakers from the outside. "I come from a long tradition of terrible atrocities committed by outside producers, filmmakers, and others who have come to Hawai‘i and just ripped off the culture, taken it back to wherever they came from without any compensation to the people here or respect for proper pronunciation of words and names. When we produced for the Department of Education, they expected the people we filmed to do stuff for free. These are Kupuna [elders], and we're going, ‘Why can't we put something in the budget to pay these people for their time?"

Their insistence on paying their participants speaks to a difference in Indigenous journalist practice versus standardized Western practices. While more journalists and media makers are working to decolonize this practice through recognizing the systemic inequity that has impacted Indigenous communities, as well as diverging values around reciprocity and respect, that directly challenges these standards, one may argue that Lander and Puhipau’s Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina was one of the earliest. In a similar vein, Hawai‘i is fostering a generation of Kānaka Maoli filmmakers who are incorporating cultural protocol into their filmmaking process. Although these practices are being overtly named now, Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina operated with an unspoken understanding of what culturally needed to be done in their storytelling process.

Chang reflects on the effectiveness of the organization’s relationship-building work, and their frequent embeddedness in the communities of focus in their films. “From a filmmaker's perspective, they didn’t capture that footage in a way that felt extractive. They were really in and of the community they were documenting and they bridged those relationships in a real grounded way. Those relationships have to be established way before you come in with a camera, and should be maintained even after you put down the camera.”

Puhipau and Lander also understood the importance of identifying similar struggles in other parts of the world, and joining forces to protect their sacred grounds. Mauna Kea—Temple Under Siege features Apache elders in Arizona, who resisted continued observatory development on their sacred mountain, Dzil Nchaa Si An, also known as Mt. Graham.

In examining the relationship between filmmaking and activism, Lander points out the ongoing movement to protect Mauna Kea. This movement seeks to protect the mountain from the construction of a 30-meter telescope, as well as from continued violations by the US military that use the base of Mauna Kea, Pōhakuloa, as the US military's largest live-fire training grounds in the Pacific. Mauna Kea—Temple Under Siege first captured audiences around the globe by illustrating the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual pain this has caused, as well as the inherent reverence emanating from the depths of the hearts and spirits of those connected to the sacred mountain. As seen in other movements, the rise in social media and technology has advanced the relationship between media and activism even further.

Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina’s legacy noticeably stems from educating Hawai‘i’s young people, as many teachers have made concerted efforts to feature their documentaries in their classrooms. This has inspired a new generation of Kānaka Maoli youth who have a greater awareness of their true history and cultural richness.

Lander is currently focused on digitizing and cataloging their work, including thousands of videotapes of raw, unedited footage. This footage will eventually end up at ‘Ulu’ulu—The Moving Image Archive of Hawai‘i, so that future generations can have access to it. She particularly feels an obligation to those whose family members are recorded on the tapes. The cinema ecosystem of Hawai‘i is proud to have birthed an abundance of creative forces. Kānaka Maoli filmmakers like Taylour Chang, Vince Keala Lucero, Justyn Ah Chong, ʻĀina Paikai, Ciara Lacy, Nāʻālehu Anthony, Alika Tengan, and Ty Sanga are examples of a rising generation that is revolutionizing storytelling and Indigenizing the filmmaking process itself.

“I don’t think any of the Kānaka filmmakers who are active now would be able to do the work that we do if it weren’t for Joan and Puhipau and Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina,” Chang says, “Forging the way for Hawaiian storytelling. And really representing the voices of Hawai‘i in a local, national, and international way. Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina is the foundation on which we stand. From a media genealogy perspective, they are the kupuna [elders and ancestors] of the work that we do.”

Raised in Honolulu, Hawai‘i, Imani Altemus-Williams is a freelance writer and emerging documentary producer, who is passionate about collecting stories that illustrate the collective experiences of colonized peoples.

Imani Altemus-Williams is a 2022 Documentary Magazine Editorial Fellow. The Fellowship program is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association. To find out more about how National Endowment for the Arts grants impact individuals and communities, visit www.arts.gov.