On the night of November 14, 2018, I was at LAX when my phone rang. Programmer Dilcia Barrera was calling to say that The Infiltrators would premiere at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. It was a deep thrill. Cristina Ibarra and I had been working on our documentary for almost eight years and the call guaranteed, at a basic level, that The Infiltrators would be seen. Like all filmmakers, our goal was always to make a story visible. With this particular film, we believed that visibility might even make the difference between freedom and deportation, perhaps between life and death—but we never imagined that impact would occur, suddenly, just three months later.

I’m a filmmaker from a family that is, on one side, recently-arrived immigrants. Some are documented, some are undocumented. When I started to make experimental videos in the mid-1990s, I decided to focus on immigration. Over the years, as I produced documentaries, fiction and even music videos about immigration, I saw the border wall grow, the detention system expand, and deportations hit record numbers. By 2010, I was wondering: Will the always-expanding immigration enforcement system ever be challenged?

The question of social change and immigration enforcement is a complex one because the deepest stakeholders—undocumented immigrants —face the specter of being “disappeared” through deportation if they encounter the government. How can a community organize and build power, when being unseen is the key to safety?

The breakthrough occurred in 2010, when a wave of activism around the Dream Act was led by undocumented youth—the “Dreamers." Young immigrants, echoing language of the LGBTQ movement, “came out," declared their status in public, and launched a massive lobbying effort aimed at the Democrat-controlled Congress, where the Dream Act was being considered. Some of those early activists were detained, but still, the movement grew. Their slogan “Undocumented, Unafraid!” was chanted in public, collectively, fiercely, in actions across the country.

When the Dream Act failed in the Senate, the activists escalated. Groups of undocumented youth got arrested in public protests to force the Obama Administration, in front of cameras, to either deport the young students, or offer some protection. The cameras were crucial and multiple. The militant actions were covered on national news, and force-multiplied on social media. The objective was no longer to pass legislation, but rather to get the President to use his executive power—his "discretion."

At this point in the story—when the activists pivoted from seeking legislation to demanding executive action—I found myself down the rabbit hole of immigration law. I learned “discretion” is a legal term that refers to the decision-making power that all law enforcement officials exercise. For example, police typically use their discretion to not investigate the crime of a driver going five miles over the speed limit. Immigration enforcement sits under the Executive Branch, and the President has tremendous discretion to set priorities. With roughly 12 million undocumented people living in the United States, who should be deported? Who should be spared? Where should resources be spent, or not?

During Obama’s first three years in office, deportations hit all-time record highs. The President said, time and again, that he didn’t have a “magic wand” to protect immigrants—only Congress could do that. However, after the massive, multi-year pressure campaign led by radical undocumented youth, Obama found the magic wand and in 2012 announced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy. The DACA victory was an incredible event in American history, a moment in which stateless people became profoundly visible and made concrete political gains.

The strategy of confrontational, high-stakes visibility was what Cristina Ibarra and I wanted to document and amplify with The Infiltrators. Putting the story of immigrant power-building on the big screen seemed even more urgent—possibly a matter of life and death—because, by the time The Infiltrators was set to premiere at Sundance in 2019, we were living under the Trump Administration.

On the afternoon of February 27, 2019, a few weeks after our premiere, the phone rang. It was Claudio Rojas’ wife, and she was terrified.

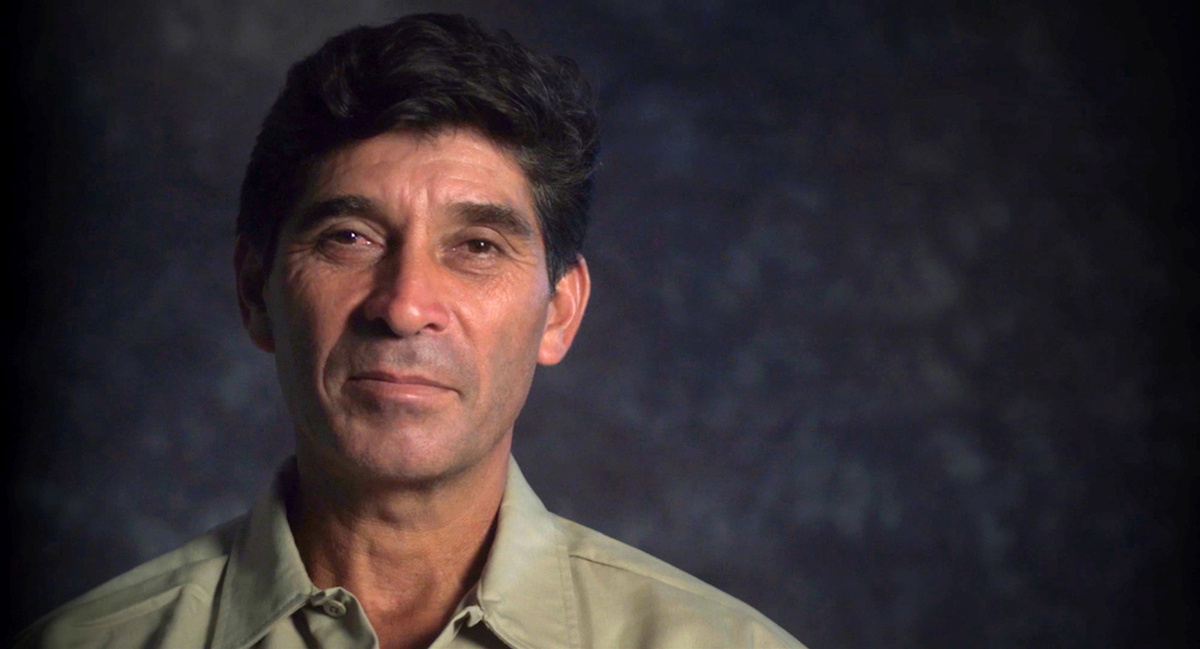

Claudio Rojas is a father of two from Argentina, and one of the undocumented immigrant leaders we featured in our film. When Claudio was detained by ICE agents back in 2012, he started a wave of organizing inside the Broward County Detention Center. The campaign would be joined by radical Dreamers who "infiltrated" the detention center to work with him. The extraordinary organizing effort, launched from inside the center, would ultimately free many detainees and become the subject of our film. Since 2012, Claudio had been free, living with his family in Florida, and speaking to journalists occasionally, including reporters from This American Life.

Claudio had also, over the years, been checking in with ICE and working to fix his immigration status. According to his lawyers, he was making progress. When his wife called, we expected to discuss arrangements for the Rojas family to attend The Infiltrators screening at the upcoming Miami Film Festival. Instead, she said, “Claudio went into his ICE check-in…He didn’t come out.” Apparently, ICE was suddenly rushing to deport him. Instead of attending the red-carpet screening, Claudio was on a cot in the overcrowded Krome Detention Center in south Florida. I felt terrified, nauseous, worried for him and his family. Everything we hoped to achieve was suddenly upside-down.

By all appearances, Claudio’s detention was retaliation by ICE for telling his story through our film. ICE was aware of Claudio’s connection to the film because, with all of our consent, Sundance had written a letter to ICE a few months earlier, asking them to waive certain travel restrictions so Claudio could attend the Park City premiere. ICE didn’t grant the permission. Claudio’s name also appeared in press coverage critical of ICE, immediately following the premiere. When Cristina visited Claudio in detention, he reported that agents told him he was being detained “on orders from someone high up.”

After 20 years in this country, Claudio was deported on April 5, 2019. He would never attend a screening of The Infiltrators in the United States, or participate in person in any post-screening discussions here.

As we worked through this crisis, we learned that a pattern was emerging: ICE was specifically targeting immigrant rights leaders, whistleblowers and activists across the country. It seemed that, far from offering safety, visibility in the Trump years put an immigrant in ICE’s crosshairs. The pattern of retribution is now well documented.

I’ve heard people say, “What do you think is going to happen, if an undocumented immigrant makes themselves visible?” That assertion overlooks a key detail: law enforcement cannot use their power of discretion in illegal ways. A police officer cannot allow everyone to drive five miles over the speed limit, except the woman organizing a protest. If a law enforcement agency uses their discretion to punish someone for speaking out, that enforcement action itself is illegal.

Federal courts are currently hearing arguments that ICE, by specifically targeting their critics, violated the First Amendment. A few undocumented activists, like Ravi Ragbir of the New Sanctuary Coalition in New York, have had their deportations stopped by courts on First Amendment grounds. This is a new and developing area of the law, but the principle is clear: No one—citizen or not—can be targeted by law enforcement as a consequence of speech. An immigrant cannot be “rushed to the front of the line” for deportation because they said something ICE does not like.

While the pain of Claudio's deportation is obviously being felt most profoundly by the Rojas family, it’s important for the documentary film community to know: This is an attack on all of us. Since this crisis began, Cristina and I have been contacted by multiple filmmakers who are producing films with undocumented folks, asking about whether or not they should proceed with their projects. The attack was clearly intended to create a chilling effect on immigrant speech, and on the work of journalists and documentarians who might want to make immigrant stories visible.

Through the process of making The Infiltrators, Claudio had become our friend. In true low-budget film form, while he was advising us on the re-creations we produced, we crashed in the same house, and Claudio attended our daughter’s fourth birthday party. Watching his family be torn apart, up close, hour-by-hour, felt like watching a taxpayer-funded kidnapping. Reckoning with the possibility that we made a film about fighting deportations that triggered a deportation felt like being trapped in a Charlie Kaufman version of Trump’s Immigration Enforcement Hellscape. I have felt guilty and stupid, and I have regrets. I try to fight all of that with the simple analysis I learned from the activists: There is no power without visibility. And in that spirit, there is no going back.

Activists and attorneys are pressuring the Biden Administration to end retribution by ICE. Documentarians and journalists are natural allies for this cause, which sits at the nexus of immigration enforcement and the First Amendment. We’re asking the documentary community to sign a petition to the Biden Administration, making two simple demands:

Prevent ICE from targeting immigrants who speak out.

Create a pathway to bring victims of this illegal retribution, including Claudio Rojas, back home to their families and communities in the United States.

The second point is crucial: To undo any "chilling effect" on immigrant speech, those who were deported for speaking out must be brought back home.

The central question every documentarian always faces is, What to make visible? In the past, journalists and filmmakers would often blur out faces of undocumented immigrants, or only show their hands as they spoke. With The Infiltrators, Cristina and I decided to go the exact opposite direction and, like the activists themselves, pursue radical visibility. That was a risk, and, for now, it did not work out the way we hoped. Our film is now one of the over 1,000 documented cases of ICE retribution. But the battle over visibility and safety is not over. We have a chance to make demands of a new Administration, to give the story of The Infiltrators a better ending, and to guarantee that immigrants and their stories have the right to be visible.

Alex Rivera is a multiple Sundance award-winning filmmaker, director of Sleep Dealer, The Infiltrators, and other films about and beyond the border.