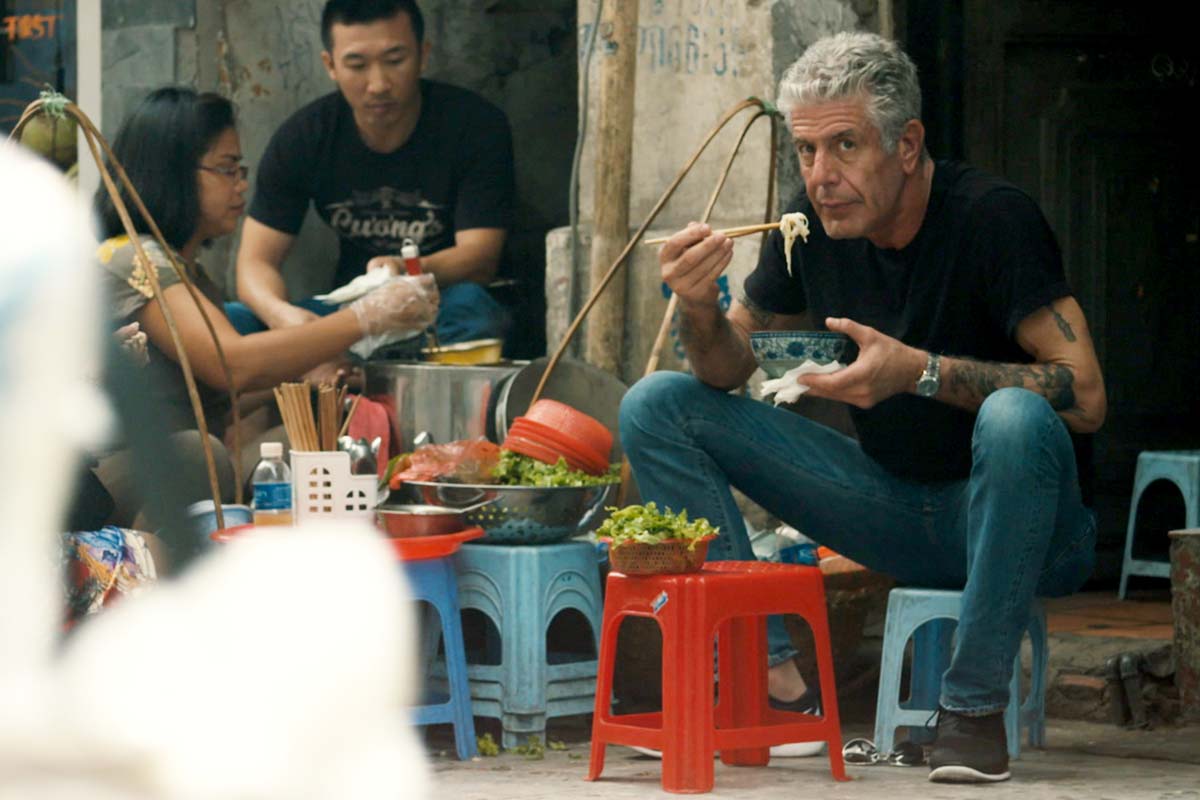

Roadrunner, Oscar-winner Morgan Neville’s documentary film about chef and cultural icon Anthony Bourdain, sparked a heated debate last summer when the filmmaker revealed to The New Yorker that three lines in the film—that sounded like they were being spoken by Bourdain, who died in 2018—were generated using AI technology. Neville explained to the magazine’s Helen Rosner that the three quotes, which were Bourdain’s written words, were spoken by an AI model of his voice created using roughly a dozen hours of recordings of Bourdain. Of his decision to employ this "modern storytelling technique," Neville reportedly said, "We can have a documentary-ethics panel about it later." But many in the documentary film and journalism communities immediately questioned whether the film’s use of an AI-generated voice of the deceased Bourdain, and the disclosure (or lack thereof) of it to the audience, was ethical—even though Neville, as he later told Variety, had the blessing of Bourdain’s estate and literary agent.

Roadrunner is not the first high-profile example of the use of new technology to seemingly bring a deceased celebrity or cultural figure back to life. Hologram technology has been used to create lifelike "live" performances from dead celebrities, including Michael Jackson. And, in 2019, reports that a CGI-created, digitally resurrected James Dean—who died in a car crash in 1955—had been cast in a new Vietnam-era film, Finding Jack, were greeted by some in Hollywood (and beyond) with horror. While it was reported that the filmmakers obtained permission to use Dean’s image from the iconic actor’s family, many were highly critical of the choice.

Setting aside the thorny ethical issues it can present, digitally recreating the voice, image, or likeness of a dead celebrity or public figure can also have potential legal implications. New York recently became the first state to enact a law recognizing a post-mortem right of publicity applicable to "digital replicas" of dead performers. And, while the First Amendment’s broad protection for expressive works, including documentary films, limits the reach of the rights of publicity for both the living and the dead, understanding the scope of post-mortem rights of publicity can be beneficial for filmmakers considering resurrecting a deceased subject for a project.

In general, whether a deceased person’s estate has a post-mortem right of publicity—essentially a right to profit from and control commercial use of the deceased’s name, voice, signature, photograph or likeness—is primarily a question of state law. Twenty-four states—including California, New York, Florida, Hawaii, Nevada and Texas—recognize a post-mortem right of publicity under state common law or statute. Generally speaking, these laws grant a transferable property right in aspects of the deceased’s persona to the deceased’s heirs, requiring consent from the holder of those rights before they can be used in commercial ways.

These laws vary significantly, however. The duration of the right—i.e., how long it lasts after a person’s death—varies under different state laws. Under California’s statute, for example, post-mortem publicity rights survive for 70 years after the death of the deceased personality, while under New York law, the right survives for 40 years. And, some state laws, like California’s, reach backwards, applying retroactively to individuals who died before the laws were enacted. The laws of other states, like Illinois, on the other hand, apply only to individuals who died on or after the date of their enactment, or the effective date of the law.

Further, some state laws, like New York’s and Ohio’s, make expressly clear that the deceased individual must have been domiciled in the state at death or, at a minimum, have resided there at death, for the post-mortem publicity rights afforded under that state’s law to apply. And some states, including California, New York and Texas require that the deceased’s persona have commercial value, thereby sharply limiting the ability of individuals who are not public figures or professional performers to invoke it..

Further, some state laws, like New York’s and Ohio’s, make expressly clear that the deceased individual must have been domiciled in the state at death or, at a minimum, have resided there at death, for the post-mortem publicity rights afforded under that state’s law to apply. And some states, including California, New York and Texas require that the deceased’s persona have commercial value, thereby sharply limiting the ability of individuals who are not public figures or professional performers to invoke it..

New York recently became the first (and is currently the only) state to enact a law that expressly addresses the use of digital replicas of certain deceased individuals. The New York statute, which went into effect on May 29, 2021, recognizes a post-mortem right of publicity for two categories of deceased individuals—"deceased personalities" and "deceased performers"—who die on or after the effective date of the law, and who are domiciled in New York at death.

Uniquely, for a "deceased performer"—defined as a person who "for gain or livelihood was regularly engaged in acting, singing, dancing, or playing a musical instrument"—New York’s new law recognizes a post-mortem right of publicity that extends, in certain circumstances, to a "digital replica," which the law defines as a new "computer-generated, electronic performance by an individual in a separate and newly created, original expressive sound recording or audiovisual work in which the individual did not actually perform, that is so realistic that a reasonable observer would believe it is a performance by the individual . . . ." Specifically, the law creates a right of action for damages for use of a deceased performer’s digital replica without consent in either a "scripted audiovisual work as a fictional character" or in the "live performance of a musical work" when the use "is likely to deceive the public into thinking it was authorized." The law expressly provides that a use will not be considered "likely to deceive," however, if there is a "conspicuous disclaimer in the credits of the scripted audiovisual work" stating that it has not been authorized. As is clear from the statutory language, New York’s new law gives rise to a claim for damages from the unauthorized use of a deceased performer’s digital replica only in narrow circumstances.

It is important to emphasize that the First Amendment provides robust protection for expressive works, including documentary films, that limits the application of right of publicity laws—both in the case of living and dead individuals. Indeed, many states with post-mortem right of publicity statutes provide express exceptions for creative and expressive works. California’s statute, for example, makes clear that it applies to the unauthorized use of a deceased personality’s name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness "on or in products, merchandise, or goods, or for purposes of advertising or selling, or soliciting purchases of, products, merchandise, goods, or services," and that "a play, book, magazine, newspaper, musical composition, audiovisual work, radio or television program, single and original work of art, work of political or newsworthy value . . . shall not be considered a product, article of merchandise, good, or service if it is fictional or nonfictional entertainment, or a dramatic, literary, or musical work. " New York’s new law is even more detailed. For example, it expressly exempts from its scope the use of digital replicas of deceased performers in among other things, works of "parody, satire, commentary, or criticism; works of political or newsworthy value, or similar works, such as documentaries, docudramas, or historical or biographical works, regardless of the degree of fictionalization; [and] a representation of a deceased performer as himself or herself, regardless of the degree of fictionalization . . . "

To determine whether the First Amendment forecloses right of publicity liability for a given, unauthorized use of a living or deceased personality’s name, voice, signature, photograph or likeness, the California Supreme Court has devised the "transformative" test, which looks to "whether a product containing a celebrity’s likeness is so transformed that it has become primarily the defendant’s own expression, rather than the celebrity’s likeness."

To determine whether the First Amendment forecloses right of publicity liability for a given, unauthorized use of a living or deceased personality’s name, voice, signature, photograph or likeness, the California Supreme Court has devised the "transformative" test, which looks to "whether a product containing a celebrity’s likeness is so transformed that it has become primarily the defendant’s own expression, rather than the celebrity’s likeness."

A recent 2018 California Court of Appeal decision in a case involving a then-living celebrity—actress Olivia de Havilland, who died in 2020, at the age of 104—helps illustrate how the transformative test is applied. The legendary actress, known for her roles in Gone with the Wind and The Adventures of Robin Hood, sued over Catherine Zeta-Jones’ portrayal of her in the FX docudrama series Feud: Bette and Joan, about the relationship between Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. It was undisputed that de Havilland did not consent to her portrayal in the series; among the causes of action de Havilland alleged in the lawsuit were violations of California’s statutory right of publicity law and common law misappropriation of her name and likeness.

Though the trial court denied a motion to strike de Havilland’s lawsuit under California’s anti-SLAPP law—finding the actress had met her burden on her right of publicity claims "because no compensation was given despite using her name and likeness" and there was "nothing transformative" about the series, which had strived to make its portrayal of de Havilland realistic—the California Court of Appeal reversed. "Assuming for argument’s sake" that Feud was a "product, merchandise or good," and that Zeta-Jones’ portrayal of de Havilland was a "use" of de Havilland’s name or likeness, the appellate court held that the series was an expressive work fully protected by the First Amendment, "which safeguards the storytellers and artists who take the raw materials of life—including the stories of real individuals, ordinary or extraordinary—and transform them into art, be it articles, books, movies, or plays." The appellate court held that the series’ portrayal of de Havilland was not actionable as a violation of her rights of publicity, and the fact that "Feud’s creators did not purchase or otherwise procure de Havilland’s ‘rights’ to her name or likeness does not change this analysis." Following the decision in FX’s favor, de Havilland sought further review in both the California Supreme Court and the United States Supreme Court; both declined to hear the case.

In sum, the First Amendment provides important protection for the use of a deceased celebrity’s name, voice or likeness in an expressive work, without the consent of the deceased’s heirs or estate. And, indeed, the use of a digital replica that appears to resurrect a dead performer or other individual for a documentary film may, in any event, simply fall outside the scope of existing, narrowly crafted state laws recognizing post-mortem rights of publicity in certain circumstances. Yet, even if permission is not legally required, there may be good reasons to obtain it anyway. including access to material filmmakers might not otherwise have. In addition, as one California court has noted, and the de Havilland litigation underscores, "Many filmmakers may deem it wise to pay a small sum up front for a written consent to avoid later having to spend a small fortune to defend unmeritorious lawsuits. . . "

While this article is intended to help you better understand the legal landscape governing post-mortem rights of publicity, it is not intended to take the place of specific legal advice from a licensed attorney in your jurisdiction. If you are an independent filmmaker who needs assistance finding an attorney, you can contact the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press Legal Defense Hotline at www.rcfp.org/hotline.

Katie Townsend is Legal Director at Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press.