'The Velvet Underground' Music Documentary Celebrates 60s Avant-garde Rock 'n' Roll Legends

By Ron Deutsch

Oscar-nominated filmmaker Todd Haynes has been fascinated with the mythology and idolatry of celebrity, and the space between artist and fan, throughout his career. The short film with which he first made his name, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987), told the tragic story of the pop singer by using Barbie dolls. Haynes returned to this theme with Velvet Goldmine (1998), a fantasy based on the careers of David Bowie and Iggy Pop. And then came I'm Not There (2007), where he explored the mythic Bob Dylan, using six different actors, including Cate Blanchett, to portray the many reinventions of the legendary singer/songwriter. And now, in his first documentary, The Velvet Underground, Haynes takes on the mythology of the eponymous group he himself idolizes.

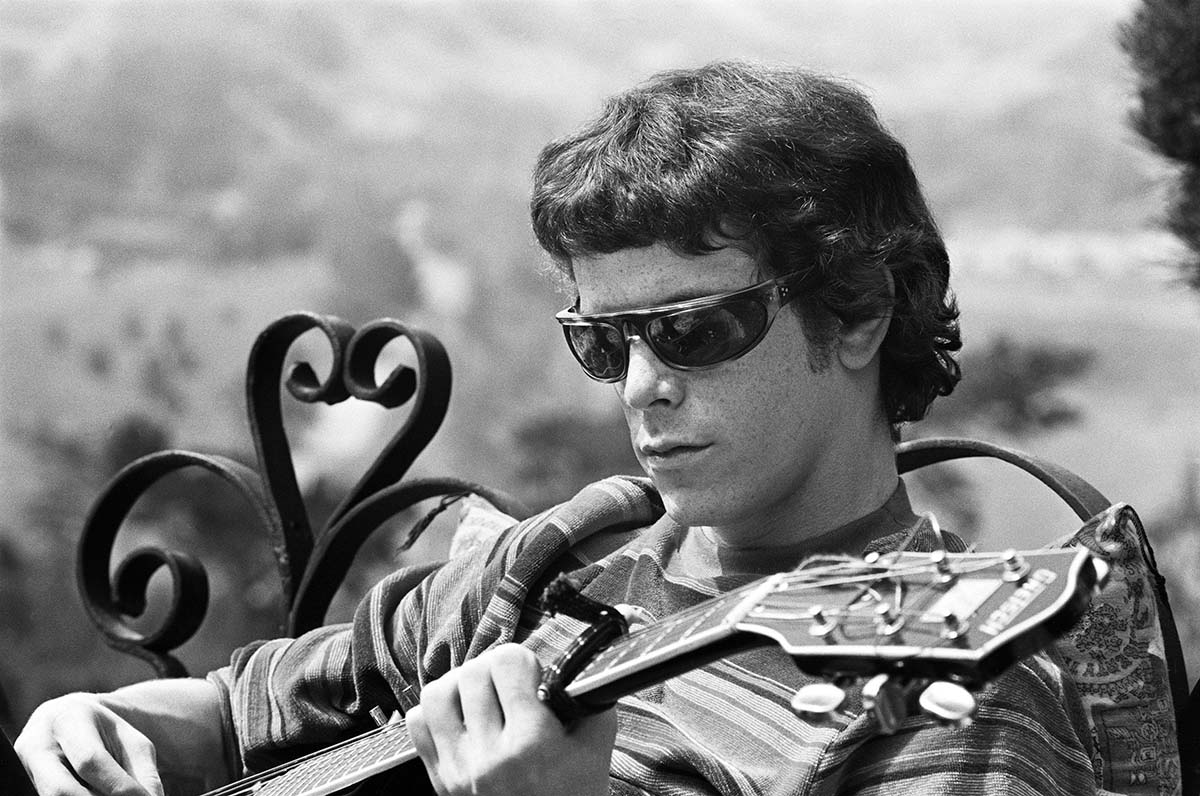

“[T]his one band was at the source of everything I was listening to—Bowie, Roxy [Music], punk, new wave,” he wrote in the press materials of his 1980s college years. “As a young gay guy, I didn’t have to read Lou Reed’s lyrics or see Warhol’s films to recognize the world being conjured in this music: its erotic charge and its drive came from its assertion of marginality... And somewhere within its cavernous sound, an understanding that creativity itself comes, at least in part, out of subjugation.”

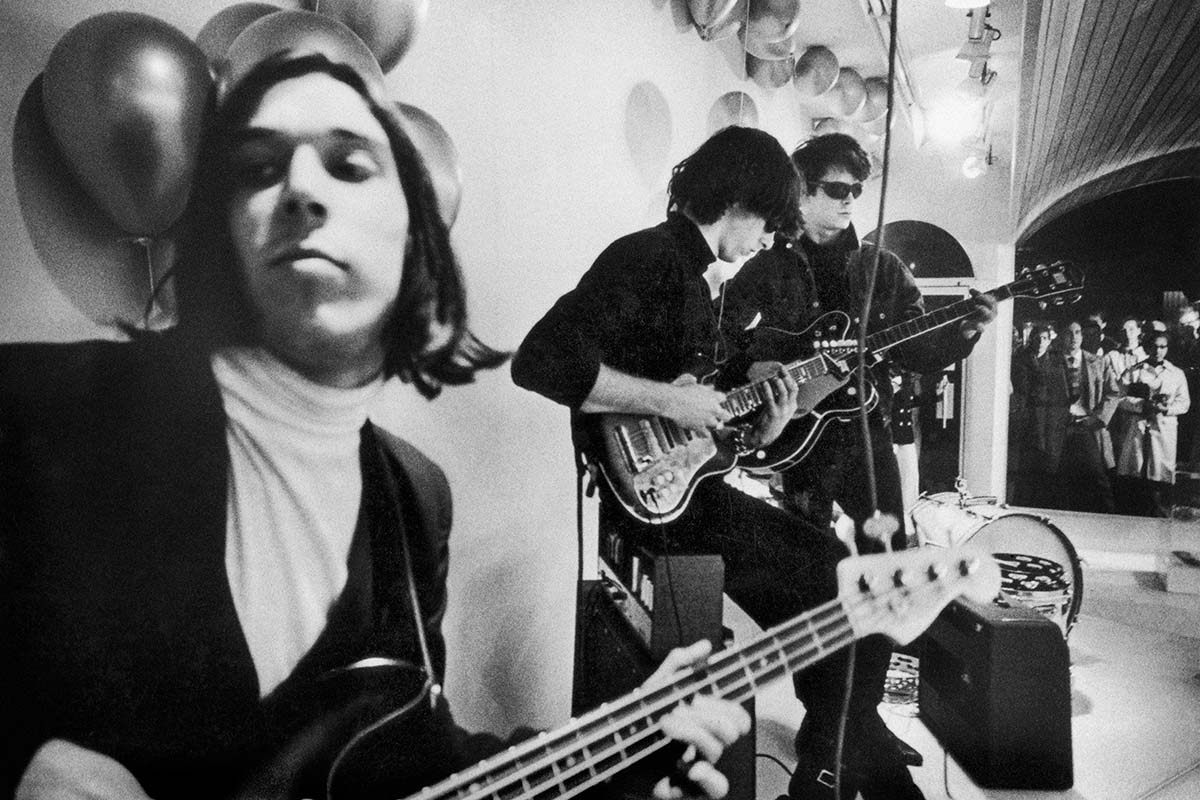

The story of the Velvet Underground began, like many rock band stories, with two very smart, talented, passionate and troubled artists, both searching to find themselves while battling inner demons of intense ego and insecurities. In this case, it was Lou Reed, the Jewish kid from Long Island in love with doo wop and early rock 'n' roll, and John Cale, the small-town Welsh boy obsessed with avant-garde classical music. The two found themselves living in an apartment in New York's Lower East Side in 1964 when they began collaborating, at first, to create music greater than either could have alone—guitarist Sterling Morrison and drummer Maureen “Mo” Tucker would later join them—then ultimately having the band implode in 1970 under the weight of their conflicting personalities. During their time together the band never really made an impact—although they had a cadre of loyal fans, including many in New York's avant-garde art scene. And yet, they seemed destined to be merely a footnote in rock history.

But then, over the course of the next decade, the band was discovered by the next generation. The Velvets, or parts of the band, did reform now and again, though the film pretty much ends with the dissolution of the group in 1970. There was a reunion concert in Paris in 1972. And most notably, Reed and Cale joined forces for the 1990 album Songs for Drella, a cycle of songs in tribute to their early Svengali, Andy Warhol, who died in 1987. The Velvets also did a brief tour of Europe in 1993, but the old wounds still hadn't healed and they canceled the American stage of the tour. The last reunion took place in 1996, minus Morrison, who died in 1995, when they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Reed then passed away in 2013. In his film, Haynes relies on fresh interviews with surviving members Cale and Tucker and archived interviews with the other members, and then restricted himself to interviewing only people who were involved with the band during their tenure, including singer/songwriter Jonathan Richman, who came under the band's spell and befriended them.

But to expect that Haynes would follow the “established” general rules of the rock documentary by including their entire “definitive” history, recount all the salacious and drug-fueled episodes, and fill the screen with a parade of panting praise by the band's disciples, is to not understand the kind of project that would attract a director like Haynes. It becomes obvious from the first moments of The Velvet Underground that his agenda is to tell the story of the band within the context of the New York art scene of the time, and specifically the underground film scene. With over two-and-a-half hours of archival material edited into a 110-minute film (and keep in mind there is very little live footage of the band, mostly shot by Warhol), we are treated to a multimedia retrospective of 1960s underground films—the documentary is rarely not splintered into multiple screens—featuring, of course, works by Warhol, as well as Jonas Mekas (to whom the film is dedicated and who filmed the band's first performance), Jack Smith (with whom Cale had collaborated), Maya Deren, Shirley Clarke, Bruce Connor, Kenneth Anger and Stan Brakhage, among others. In a way, the Velvets' music and story almost serve as a backdrop to the kaleidoscope of film clips. Haynes is immersing us in this world to get us to understand the context of the time, as well as to celebrate that era and place the band within this context. He further seeks to demonstrate how the Velvets are perhaps better understood as more “musical art” than just another rock band.

Haynes became involved in the project after Lou Reed's widow, musician and multimedia artist Laurie Anderson (Heart of a Dog), made his archives available to the New York Public Library. As Anderson, Reed's surviving family, and executives at Universal Music Group considered that perhaps it was time for a Velvet Underground documentary, Haynes' name came up. He was approached and he accepted the challenge.

Documentary spoke with Haynes via Zoom to discuss the project, the band and its influence in the world.

DOCUMENTARY: After watching the film, the first thing that struck me was how the tone and feel of the music translated into the film; it really felt like you achieved a cinematic representation of the band here.

TODD HAYNES: Yes, great. One of the first and most interesting challenges about approaching music that was finally getting its due was, How do you hear it fresh? What was it exactly that was different about them? So everything was about getting back to the time and place that produced the band and its music.

But because of, or in addition to, all that, what was even more of an invitation to do so was that the time and place was everything. It was such an incredibly rich and “promiscuous” creative period when all of the mediums of art were curious about the other and starting to try to break down the boundaries between visual art and film and music and happenings and poetry and jazz and all this stuff. And you had everybody in this tight proximity in New York City, where you could physically be exploring all these things in person with everybody, and everybody seemed to be doing that every night. With all that, what we have is all this amazing avant-garde cinema as well as all this avant-garde music being explored, particularly on the John Cale side of things, that also bears a curious resemblance to a lot of the experiments that were going on with the filmmaking by Andy Warhol and others. So yeah, I wanted to try to really exploit all of this stuff, which was basically being handed to me on a platter, and let it tell the story of this band and let you hear the music in a fresh and vital way.

D: It does seem that time has passed for this kind of real-time mingling between the arts, what with the internet, in many ways.

TH: It's hard not to look back at those times in our own lives, or to be researching and hearing about times that preceded our own generations and not feel envy for the past. That great sense of place that brings people together is incalculable. You can't really find an equivalence when people are all remote from each other, or at least we don't know what that's exactly like yet. At the very least, we can say things are different. Maybe they're not worse, but they're not like that. I do recognize that it was a factor in concentrating a lot of creative energy in a certain time and place.

D: You've been fascinated with rock mythology and rock idolatry—and the space between artist and fan—throughout your career. What is it that fascinates you about it?

TH: I definitely feel like when you say “rock idolatry,” the title that really comes to mind of my work is Velvet Goldmine. Questions about identity are always interesting to me—how pop culture offers ways of playing around, undermining, or dressing up notions of identity, making us question the veracity or the stability of identity. With Velvet Goldmine it was really about how the fan gets invited into that process through mirroring the musicians, dressing up like them, trying out different kinds of selves and sexualities and looks and hairdos, and turning it into a sort of cosmetic and theatrical endeavor that's very liberating. That certainly makes a lot of sense to teenagers who are still figuring themselves out. Whereas the Bob Dylan movie [I'm Not There] was also about identity, but really more about how this artist navigates a very complicated world with a lot of investment in his work by throwing off or shape-shifting or rejecting the identity that he assumed yesterday, so that he has a kind of creative freshness to go somewhere else, and how this mirrors aspects of American culture or traditions.

[The Velvet Underground] is a little less about idolatry. One could make an entire film, or more, about the Velvet Underground, and in ways, that's the Jonathan Richman part of it. It was kind of a surprise to me as he sort of speaks for all fans of the band, but he also just happened to be the one who was invited in and got to maintain a permanent position there, against all odds, as a regular witness

to the band. I also think “mythology,” but definitely a real practice of questioning conventions was informing artistic language at the time. And not just conventions of form and style, but conventions that extend to identity or notions of heteronormativity. And that counter-counter culture, which the '60s sort of was for me, was something I always wanted to hear more about from the people we interviewed.

"That counter-counter culture, which the '60s sort of was for me, was something I always wanted to hear more about from the people we interviewed."

- Todd Haynes

D: Speaking of Velvet Goldmine, I re-watched it after The Velvet Underground, and there was a line in the film that just stood out, and maybe is a key theme in all or most of your films. It plays into this mythology thing, as well as speaks to film, celebrity and to a larger extent, society, culture and specifically gay identity: “A man's life is his image.” And I thought, There's Todd Haynes talking.

TH: Yeah, though that line may have come from Oscar Wilde—a lot of lines in that film are Wilde or “Wildean.” People talk about Lou Reed, Warhol and the whole Factory scene as a sort of contemporary Baudelairian dandy era, which to me just might be a way of saying that even if they weren't literally dressing up and putting on make-up—though Lou Reed would soon be doing that after the Velvet Underground—it was a way of masculinity being undermined, basically asserting a kind of “faggotry” as the operative mode of the kind of scene. On the one hand, it serves as a kind of silliness and trivializing [putting on an overly deeply serious voice] “very serious abstract expressionist ideas of what art is.” But then also just saying, “Fuck it! Art can just be a picture of Marilyn Monroe. Art could just be the latest headline in the news. Art could be this or that.” Warhol knew he was really asking major conceptual questions when he was doing all that, but he was doing that without acting seriously. And that was also part of the pose. All of those things are components of this way of challenging a kind of self-seriousness that preceded this era, and yet was also still prevalent. I think when the Warhol scene and Velvets collide with West Coast hippie culture, they're also colliding with a different form of a kind of pretentious seriousness about how we're going to [putting on a hippie voice] “change the world and we're going to become better, whole people.” All of this was looked at with a little silliness by the East Coasters, and in it they saw conventional thinking while they were practicing something very differently in their world.

D: That leads me to a kind of sidebar. There's a scene in The Velvet Underground where the band is talking about Frank Zappa and how they hated the whole West Coast/Hippie/Zappa thing, and then in Alex Winter's recent documentary Zappa, Zappa says almost the same thing about how he found the whole New York/Warhol/Factory scene to be full of crap. Also, Alex's parents were part of that avant-garde underground cinema scene, and he, as you've done here, used his film to make a kind of homage to that scene. So you have these two bands and two films and it's like they both stated how they hated each other so much, but then perhaps also were very much alike. And then to bring that all together, I was looking up the video of the Velvets’ induction to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the next video on the queue was Lou Reed's induction of Frank Zappa, who'd passed away. And in his speech he says, “[O]f the many regrets I have in life, not knowing [Frank] a lot better is one of them... I admired Frank greatly and I know he admired me.” It's all showbiz, right? It's all about that posturing you were talking about.

TH: [Laughing] I forgot about that!

So, yeah, it's like having to stake your territory and create a sense of opposition to anything around you. For example, the Velvets were hyper-aware of everything Bob Dylan was doing at the time in New York. No one was disinterested in what he was doing, no matter how much they say so. It's that adversarial thing that they needed, that artists do need to have a vital creative point of view. In the 1960s, there was so much amazing stuff going on all around you. So it must have taken more defiance to just say “no” to so much, whether it was Beatles or the Stones, but especially anything that was at least close to what you were doing. Then you staked out your territory and had that little bit of space that's yours to make your art in. I do recognize there's something adolescent about it. Maybe that's what Lou Reed was coming around to as a grown-up and acknowledging Zappa and all that. But I also recognize that the rejection was necessary. You need to say, “Fuck you.” And that's what the punks took from the Velvet Underground, and so many other genres of music would take from them as well.

It's hard not to see the Velvet Underground as the kind of root to so much of music that basically started to tell you the “bad news,” not the “good news.” It was basically their report on: “I fucked up. I don't know why. I don't like myself. I sometimes want to off myself, or at least evacuate. I want to shoot heroin and disappear.” There was something unhealthy about the message, and it wasn't necessarily directed at a political system or oppression, like some of punk rock has been. It may not have always been overtly about sexual identity, like glam rock was starting to be more aggressively traded in. But all of that was there. And it hadn't been there before. Most of the messages of popular music and R&B and rock 'n' roll were affirmative before the Velvet Underground. So I think it opened the possibility in sound, tenor, and messaging of a whole different kind of experience of the world that hadn't been very well established and documented in music.

D: I would suggest that because there was actually so much turmoil in the '60s; while the music was a lot of striving for peace and love, there were riots and assassinations and the Vietnam War all going on. I think why it took until the '70s for the Velvets to find their audience was that the '60s had to be over for them to be appreciated.

D: I would suggest that because there was actually so much turmoil in the '60s; while the music was a lot of striving for peace and love, there were riots and assassinations and the Vietnam War all going on. I think why it took until the '70s for the Velvets to find their audience was that the '60s had to be over for them to be appreciated.

TH: Yeah, there needed to be almost a safe space for it to happen. It's not to say you can't find examples of dissent and pain and angst in the music of the '60s, nor is that some way of defining value of one kind of work against another—you know, that unless it's dark and transgressive it doesn't have the same integrity or heft. I don't believe any of that. Also we have the entire history of the blues in America. The blues was a way of surviving pain and transforming your existence by the very fact that you could make this music that could become a euphoric expression of human endurance as a result of adversity.

D: And to add this into the mix, the Velvets were so influential in places like Czech Republic and Spain, for example, where because of their repressive governments at the time, this music was incredibly transgressive and illegal to even consider then. So many artists in those countries were getting these “reports” and it gave them hope for something transformative. I mean, there was an actual Velvet Revolution.

TH: I think what's so interesting is how the Velvets’ music is interpreted within different regimes, different repressive, fascist governments. It never had an overt political message, and there were other songs and music that did. This is more in keeping how I think it becomes a relevant source for punk; it's interpreted as protest at a kind of psychic level, kind of an internal objection to the conditions of the world, without necessarily having some sort of Marxist or progressive politics solution. I would think if you asked the band themselves about anything they thought they were trying to recommend as solutions, they would say, “No, we don't offer solutions. What we offer is an acknowledgment of struggle and conflict.” And a lot of that turned inward, not necessarily outward into political practice or reform.

I love that of all the bands you might pick, it wasn't Bob Dylan that fueled the Velvet Revolution; it was the Velvet Underground. It had a lot to do with the individuals and their generation and where this music stood, or needed to be unearthed, and that gives the listener, the lover of the music, a role to play. It basically demands action, in a way. When you think of the famous Brian Eno line that nobody bought their records, but the 5,000 people who did, all started bands—to me, that's infinitely interesting and not just a colloquialism of the band. It really describes something even bigger than what we're talking about. It enlists you to do something with the music. It makes you creatively responsive, or politically responsive, to the music. It makes you think it's possible for you to do something. And that's true for all great art.

"It's hard not to see the Velvet Underground as the kind of root to so much of music that basically started to tell you the “bad news,” not the “good news.”"

- Todd Haynes

D: Just to switch gears, you and your producer Christine Vachon brought in the seasoned documentary-producing trio of Julie Goldman, Carolyn Hepburn and Christopher Clements to help produce the film. How did that relationship come about? How did they contribute to the project?

TH: It was Christine who basically said that we need documentary producing partners on this movie, as we'd never done one before. It took all of what felt like five minutes to convince them and identify them as the best possible partners. We just met up and talked and felt such kinship with those guys. It proved to be so true in ways I can't even quantify. All three of them were just amazing people, but the way they divide their energies as a company and as creative partners was remarkable. To me it's still a mystery how a documentary gets financed and distributes resources over such a strange and very different kind of schedule than a feature film.

That also kept our first editor, Adam Kurnitz, busy for nearly a year before [editor] Affonso Gonçalves and I were free from my last feature to totally join in. I had already filmed all the interviews in 2018, but then I had to work on a feature and Affonso was cutting. Adam and Affonso had first worked together on the Iggy Pop and the Stooges documentary, Gimme Danger, directed by Jim Jarmusch, and they had a great experience and relationship. So I met Adam on his recommendation and just loved him. But it took our own little village of people. My partner, Bryan O'Keefe, is a researcher and has a library arts background, and has done research on almost all of my movies. He's an archival producer on this film and he began the process of going in deep and creating the list of titles of films we wanted to put into our database for editing. And it was Julie, Carolyn and Chris who would facilitate all that. They were also there with me in the research stage of prepping the interviews. They were so completely thorough and limitless. Then Carolyn moved into the process of licensing all the clips and archives, which was a massive undertaking, especially during COVID.

D: So do you think after this experience you'd make another documentary?

TH: I would do another documentary, but I don't know what it would be. But yes, absolutely.

The Velvet Underground will be showing October 14 as part of the IDA Documentary Screening Series before opening in theaters and online October 15 via Apple TV.

Ron Deutsch is a contributing editor with Documentary. He has written for many publications including National Geographic, Wired, San Francisco Weekly and The Austin American-Statesman.