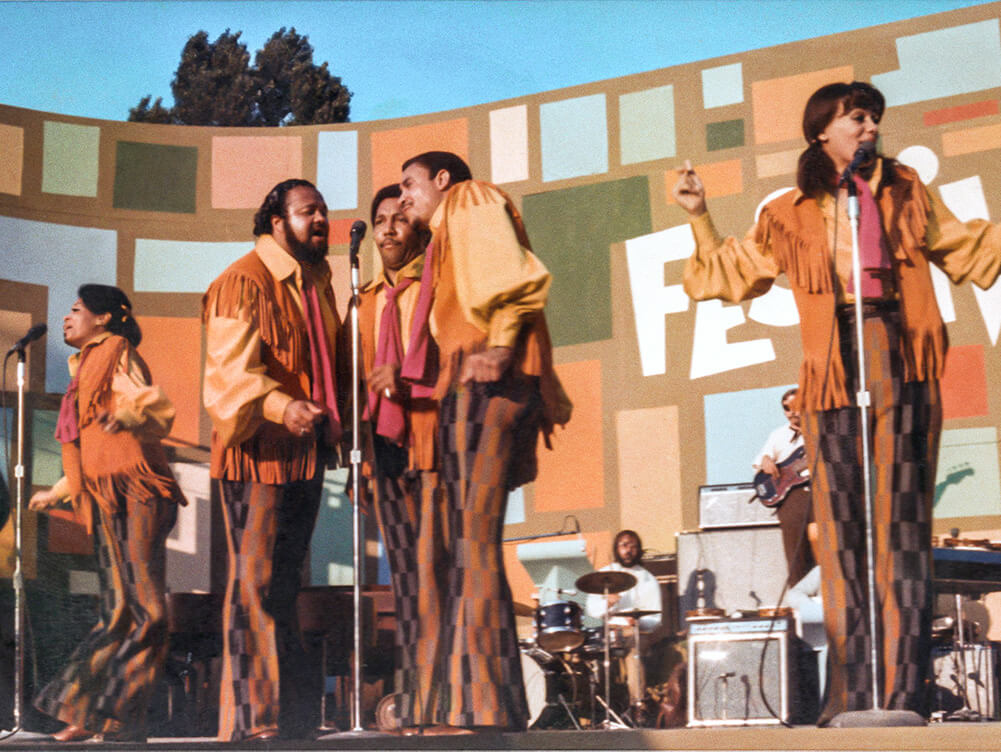

Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) is the directorial debut of Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson about the Harlem Cultural Festival of 1969, which came to be known as "Black Woodstock." Six weeks. Six free concerts. 300,000 people. A feast for the soul, the concert featured otherworldly performances by Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder, Gladys Knight & the Pips, the Staples Singers, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King, and Nina Simone, among other legendary artists. The footage from the Harlem Cultural Festival had lain dormant in a basement in New York; the late filmmaker Hal Tulchin, who, according to his obituary in The New York Times, had shot 40 hours of footage on four portable videotape cameras, had failed to generate interest among the television networks at that time.

After opening the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, Summer of Soul was awarded both the US Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award in the US Documentary category. The revelatory documentary makes its premiere in cinemas through Searchlight Pictures and on Hulu on July 2.

I caught up with Questlove as he was off to camera-block that evening’s taping of The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, featuring his Roots bandmate, Tariq "Black Thought" Trotter. With a shared passion for capturing and illuminating the legacy of our lesser known but historically significant cultural watershed moments with a treasure trove of archival, Questlove mused on the music and the inspiration for his filmmaking: centering pure Black joy.

MELISSA HAIZLIP: I’m so excited to talk to you about Summer of Soul. You and your team have made an extraordinary film.

AHMIR "QUESTLOVE" THOMPSON: Yeah, I had to enlist the best. You could say that my early initial trepidation was like having just gotten my permit and then the first car you drive is an 18-wheeler. Actually, what it wound up being was like a crash course on how to effectively tell stories. I’ll say that the one thing that aided me here, that normally when curating—be it my own albums, or someone else’s record, or even our podcast, or the books I write—is I’m under the impression that you leave nothing out. I feel like the visual media is the one area in which editing is so, so, so crucial.

My first cut was three hours and 20 minutes. Some people will make documentaries on subjects that have hardly any footage to go on; it’s almost like you need a lot of broth, very little vegetables and content inside the stew. In this case you have way too much food and no room for the broth. So, dropping magic on the cutting floor was one of the hardest things that I had to learn to do. But now that we have the finished product, I almost feel like you got to leave space for someone’s imagination to creep in; it’s been a great learning curve.

MH: Speaking of your directorial debut, tell us about what the intent was for the film, and exactly what do you think, now that you’ve had some time away from it, makes it a Questlove jawn?

AQT: Well, the intent of the film is kind of a loaded mission. As a musician, these are precious artifacts that are historical, but then on top of that it’s really making sure that it gets its right place in history.

At the time I happened to be finishing up Prince’s autobiography, and he’s telling this warm, fuzzy memory that he had of his dad taking him to his first movie when Prince was 11, which was Woodstock. He explains how that changed his life; the legend of Woodstock and the light we hold Woodstock in—all that happened because of the movie. Granted, the lineup was enough to make people from all parts of the country take a pilgrimage. But all the acts, all the memories, all the images, anything that we associate with what we think the ’60s were, chances are you’re either thinking of the March on Washington or you’re thinking of Woodstock.

For me, I still got immersed and baptized in musical education without having a Woodstock of my own to claim. But I always wondered, if this [original concert] film were given the greenlight to be just as brilliant as it could have been, what a difference that would have made in the lives of young musicians such as myself, who really didn’t have musical documents growing up.

Thank God I had parents that were super hip and super cool, that would wake me up at 11:45 p.m. so I could watch the second song on Saturday Night Live before Soul Train came on. Philadelphia was weird. It was one of the markets in which Soul Train would come on at 1:00 in the morning instead of 12:00 in the afternoon like the rest of America.

So, I often wonder, had this film come out, how different music could have been. Because Woodstock defined a generation. This could have defined us, and it’s sort of weird what Soul Train wound up doing. But, no more "would’ve, could’ve, should’ve," I think that this film is still potent and it’s timeless and the fact that it’s 50 years later and we’re still talking about the same issues will show how valuable it still is.

MH: And as we’re moving through this tumultuous time, this 21st century, the millennium, what you’ve done—pulled together these archives, created a score, curated this history—this is a Black cultural experience, but it’s also a universal experience. Your first cut was three hours and 20 minutes; talk about your process in making the film—around letting certain sequences breathe, and then cutting down others?

AQT: Well, in this case, time was really on our side. In his mission to sell the film, Hal Tulchin probably gave it one last go-around with the 25th anniversary; I think in 1994 he tried to make something happen. What winds up happening is, once we got the original reels, that process alone to transfer took a good five months. They had to bake the film, take a very sensitive bristle device and gently restore the film without scratching or destroying it.

I took the transfers that he made to VHS, which we transferred to DVD; even though it was four cameras, it’s 20 hours of unique footage. I basically made that my visual aquarium for those five months. Instead of sitting here with my pad and pen and just watching everything, I wanted it to naturally hit me. So, all the TVs in my house, in my office at NBC, my laptop—it was like a screensaver. The concert just constantly played for 24 hours. I kept notepads next to each monitor in my house.

I’ll say that for me the most important thing was, I wanted my first five minutes to be like a gobsmack, just totally surprise you by what you were watching. And I felt that nothing spoke more of that surprise than Stevie Wonder playing drums, which shocked even me! Everyone knows I’m a drummer, so of course I’d be attracted to this, so that’s the beginning.

This is also how I plan shows. I feel as though most people remember the first ten minutes and the last ten minutes of any show, but it’s almost like, what’s in between doesn’t matter. Yes, in this case it does matter, but for me, it was like, when people first see this, what do they see and what do you leave them with?

But also, I gave permission for [producer] Joseph [Patel] and everyone to really speak their voice and let me know if I was trailing off into amateur-hour territory. For the ending—initially I thought well, obviously, Mahalia [Jackson] and Mavis Staples have to close this; that’s the most magical moment of the thing. And then Joseph challenged me.

I felt it was more dangerous and edgy, and it spoke more of today to let Nina Simone have the last word, especially with "Are You Ready, Black People?", with her challenging people to immerse themselves. We live in a time where a lot of performative activism is trying to masquerade itself as actual activism, especially with social media. Once we shifted Mavis and Mahalia to the middle, it elevated the film even more, then of course, Nina’s fiery performance was the hardest to break up because that entire 45 minutes was the most magical. I’ve never seen a person just so sure of themselves in new territory. She’s not singing jazzy love ballads like "My Baby Just Cares for Me." She’s going into a new territory of activism. So, once you have those three, the story writes itself. And this is a story of change.

In 1969, younger activists were at a newer place than the older activists were. We started calling ourselves Black, our fashion and ideas got bolder, there was the voices of the Black Panthers versus the earlier ’60s civil rights..Attitudes had changed. So, it’s just filling in the blanks, really.

MH: And it was just so exciting to see what kind of story you would tell. I know that you believe that the film is so much more than a concert film. It’s not just about these extraordinary performances, but the decisions you have to make about constructing the narrative out of the material you had, and the themes that you wanted to embrace.

AQT: I’ll admit that this sort of fell in my lap, at maybe the tail end of 2016, or early 2017. I had a friend that had a copy. If you remember, Aretha Franklin was key in keeping the Amazing Grace film from coming out when she was living, but I had gotten to watch maybe 35 minutes of it, because a friend of mine had a cut of it from years before, and I always thought it was such a bold choice to show the performances with no context whatsoever. But I’m a guy that lives for Easter eggs and director’s commentaries and all those things, so immediately I started stalking anybody involved in that film. Once I heard the backstories, a part of me was like, Wow, is there a way for me to include those things as well, in this film?

So, in the beginning I kind of decided, OK, let me curate a really good, tight, two-hour performance and just make you a fly on the wall. But the more these stories kept revealing themselves, the big question was, Do we have people that attended the concert give commentary? We found about ten to 15 people, and even that was hard because you were either under the age of 10, so your memory might be spotty, or you were over the age of 75 and your memory might be spotty. For me, Musa Jackson was probably the gamechanger. He was our first interview, and the thing that I never considered was the fact that this concert was his very first memory.

MH: He was five when he attended the festival, right?

AQL: Right, so when this concert winds up being his very first memory in life, you’re watching him have such a genuine, honest response to it. Like, tears immediately came to his eyes. A lot of Musa’s childhood memories were just sort of locked away. It’s almost like, was it real? Was it not real? To watch him have that response really opened the door of, Okay, we really have to make this of the people.

The fourth camera was probably the most interesting because it only focused on the audience. So once that happened, the floodgates opened. Then once we started talking to the artists, they opened up so many doors of things that we didn’t even know. Facts about the festival itself, and even their lives.

MH: You mentioned in a Sundance Q&A that it was "the Mount Rushmore of music." Just having Sly and the Family Stone there—1969 is Sly’s breakthrough year, right? Wasn’t it two weeks before he played at Woodstock?

AQT: Exactly.

MH: So, was Sly and the Family Stone the footage that you watched first? And why did you choose to watch that first, when you first sat down to tackle the footage?

AQT: Actually, the Sly footage found its way into my life without me knowing what the context was. I went to Japan in 1997 and a giant collector of rare footage showed me the footage. At the time I think it was mistitled, like Dallas Music Festival or something. I had no idea where they were. It's not like he mentioned Harlem or anything.

I didn’t realize the context of it until I got the footage back. I just left everything on random. So, I will say that Motown Day was the day I started with first. And then probably the biggest shock of Motown Day was when Stevie Wonder mentions the Apollo [11 space mission] and man on the moon, that day in July, and you hear boos from the audience. I was like, Aait, whoa, was that a boo? I grew up in a time period in which, especially with the schools I went to, they didn’t put things in proper historical context. So, for millions of people, if you’re taught history, that’s not your history. I just grew up thinking, Hey man, this is a great achievement for man; we’re on the moon, this is awesome. So, I was rather shocked: Why are they booing the space program?

And the more we investigated, we realized that CBS News had a report and I almost feel as though there is an underhanded kind of, "Okay, where can we go to get people’s opinions? And oh, there’s that festival in Harlem, let’s get their opinion on it." It’s like, come on, you know what we’re going to say! So that was the one thing that we definitely felt was important to show. I really didn’t know about the absolute waste that most Black people thought landing on the moon was, when we can’t even finish what’s here on earth.

MH: And it’s such a great line, in that wonderful archival footage outside of the concert: "Never mind the moon, let’s get some of that cash in Harlem." A brilliant way to contextualize what was important to our people and feeling neglected by our own country. But feeling the love in that context, in that concert, and why that was so important for us.

AQT: Exactly. Probably the one thing that also dealt with it that we didn’t have enough time to just quickly dabble in was the comedy element. So, you have Pigmeat Markham, Moms Mabley, Willie Tyler & Lester, George Kirby. Next to food, comedy is the one element of art where time is the enemy. It was interesting to see what the level of humor was in 1969. You’ve also got to understand that the entire narrative and direction of the film changed once we went into the pandemic.

MH: Of course! I was going to ask you about that.

AQT: Just the amount of stories that Stevie Wonder had and the Staples Singers had, and Gladys Knight—they talked about their run-ins with the police. Maybe for a second, we even considered, Should we show modern protest footage? But then it was Captain Obvious that we are living in the same time warp; there’s no need to beat people over the head.

MH: Exactly. And what a herculean effort you have to make, because you’re dealing with this other timeline as well, and what’s happening in the zeitgeist in order to contextualize this story you’re telling. But not only that, you’re also bringing this footage alive, and you’re also putting it in this context, and ultimately what it means in 2021, or how to recontextualize it through a 21st-century lens.

AQT: I think we left enough space for people. For me, at least, if you spell it out too explicitly, that sort of takes the fun out of the game. People love the art of discovery.

MH: In addition to deejaying, among other things, you’re an exquisite musician and drummer. So of course, I couldn’t help but notice how you highlighted the incredible drummers from the concert in the film: Stevie Wonder, Sheila E, Greg Errico, Max Roach. Tell us about that, because the footage with Stevie is extraordinary.

AQT: Yeah, there were a lot more. One of our interviewees, Darryl Lewis, said [of Sly and the Family Stone drummer Greg] Errico, "Do you know what a statement that is when you’re in a Black band and you’re the white guy playing the drums? Do you know how good you have to be?"

Once I realized that there were seven really unique drum solos from all those drummers, I initially entertained the thought of doing a supercut. To me the drums and their history, and our story as Black people went hand in hand. And the drums weren’t just a metronome source; it was way past a communication device.

But, yeah, just as a drummer, it’s a way to put my personality in without having to be in it.

MH: Exactly. It’s also a wonderful method of storytelling. And it feels like you’re using music the way we feel it as a people. It’s a character in the film, just like it’s the soundtrack of our lives. It’s really much more than just an audio moment. And this constant conversation with the rhythm also impacted the percussion, and the rhythm of the film. And I thought it was just genius the way you used your drumming sensibilities to not just be percussive, but to really be a music aesthetic throughout the whole film.

AQT: With Josh Pearson, our editor, I knew that he’d understand my musical sensibility. So a lot of our edits and our cuts had a rhythm to it. I feel like there’s a rhythm feng shui thing going on. In the beginning I didn’t think it was possible because I thought, Ahh, man, I got to micromanage, stand over his shoulder and say like, Okay, this rhythm I want, like notate a rhythm to him and that sort of thing.

But Josh was way ahead of me as far as knowing exactly what I wanted, as far as the edits were concerned. He was able to see the vision on the moon landing, how we were able to find space in between the lyrics of the Staples Singers song, talking about man on the moon, and having those contrasting opinions. To me, that’s engaging and rhythmic and it keeps the audience interested.

MH: Now of course we’ve got to talk about how you achieved the incredible sound for the film. I would imagine it was a challenge, as a purist, looking back at the archive and wanting to honor it faithfully. But also thinking about a modern-day audience, and what we expect to hear because we’re used to 5-1 stereo. How did you find that balance between keeping the archival and the artifacts of the nitty-gritty, dirty, live vibe and making that audible for a contemporary audience?

AQT: Visually and sonically I wanted it to be as true to 1969 as we could get it. The one thing that I would love to really take credit for was the sonic miracle that was the mix. Hal Tulchin’s widow let us go through his basement archives, where a lot of our questions were answered because he kept all the paperwork, he kept the backline, he kept what was rented, he kept the blueprint of building the stage to the soundboard. I was amazed that it was only 12 microphones; when you watch the movie the way that I did, you have to watch with a different set of ears and eyes.

We gave the mixes and the reels to Jimmy Douglass, one of my favorite music engineers. He started with Barry White when he was 17 years old and he’s gone through a whole ring. I got familiar with him once Timbaland made him his engineer. Jimmy incidentally also did the Amazing Grace movie. He really gave us a great mix. We did a 5.1 and we did a Dolby version. The way that B.B. King’s performance comes off in the movie theater; it’s literally like you’re sitting on stage listening to how clear and crisp it is with very minimum amplification. It’s so weird that that’s the one thing that I’m taking away from this movie that I might apply to my real life.

I called my manager and said, Look, once we "get back to normal," I want to do a week inside of a theater to see if I can rise to the challenge of just 12 microphones the way that it was mic’ed on the festival to see if it will sound the same. Can you imagine that? The Roots use 76 outputs. Meanwhile, that concert just puts us to shame!

MH: What were some of your other goosebump moments, or Easter eggs, that you found in the footage, that either you were able to keep or you had to leave on the cutting room floor?

AQT: You know, I’m the guy that always sits in the movie theater and watches every last credit. So I instantly knew that I wanted to do an Easter egg with the comedy bit with Stevie Wonder and his music director doing that whole "get yo’ hand out my pocket" thing.

The things that I fought most to keep in were not only important to put things in historical context, but just as a musichead, there’s a lot of things that I was interested in that maybe the audience wasn’t interested in.

MH: And so, when you were interviewing people, even during the pandemic, were you able to go down those rabbit holes, or were you able to find these revelatory moments as a director?

AQT: Probably more. As I said at the top, Time was really on our side. So once the pandemic started, I will say that the only one slight, "Dang, we could have had it," was really just getting Mavis [Staples] on film. I wish we could document how we actually conducted her interview. It was sort of like watching that Rover machine on Mars. We would go to her apartment complex and remote-control this wheeled device in front of her door and inside of her apartment so that it could interview her. Only because we wanted the sound to be perfect.

Once the pandemic hit, we lost a few things. I felt like Harry Belafonte was so instrumental in the story of Hugh Masekela coming to America. But we had to lose that interview because we didn’t want to risk his health.

During the pandemic, sitting still and not having to work on my album and work at The Tonight Show – those first five months in which we had nothing to do but concentrate on the movie, that really sent us into high gear, into our creativity, which I think shows in the film.

MH: Exactly. I’m reading Daphne Brooks’ book Liner Notes of the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound. And I was reminded of an article she had in The New York Times, about the 50th anniversary of the Harlem Cultural Festival in 2019. And she really articulated this idea that we have these large-scale African American pop concerts and events, and they really become this sort of community revival. And it’s a recurring phenomenon. But one thing that’s beautiful about it is it also gives us this window into Black joy. And for me, and for many, the film was revelatory in capturing that pure Black joy. We’ve just experienced so much trauma, that’s it’s really wonderful to be able to see just a beautiful, joyful film. Can you talk about the significance of centering Blackness in your film, and specifically, trauma-free Blackness?

AQT: It’s so natural that you almost take it for granted. The true reward in doing all the research was the fact that you have the ability to watch the fourth camera, which I call the audience camera, in which you get to watch the audience’s reactions. That’s when my brain just exploded, like, Wow, let me find out why I like watching the audience watching this concert, more than I like actually watching the concert.

For me, because of the way white guilt often works, there might be this notion that we don’t want to drop the ball in telling a particular story because pain is such a common DNA in our existence. From us coming here, to us trying to navigate our lives here, for us trying to keep from drowning, and not only surviving, but trying to thrive in this system that’s rigged for us to not make it. Post-12 Years a Slave, I believe that’s when we finally reached our breaking point. Like, OK, no more trauma porn for a while. There’s a PTSD factor. When I watched Birth of a Nation, I couldn’t move out of my chair for like 25 minutes.

I think oftentimes there’s this perception that there was never, ever Black joy in existence for our history here. That we came here with this history of pain and sadness. When in actuality, there was music that was created, technology was invented, and all things creative and majestic. We’ve somehow managed to thrive and exist despite what’s there to hold us back. I knew that this would have the same effect. This is why Soul Train worked: It was one of the first times in television history that you got to witness a person’s history, Afro-futurism, on a weekly basis; that’s how Black joy was mass-marketed. Again, [Summer of Soul] had the chance to be that starting point, but Soul Train reaped the benefits of being the first true documentation of Black joy. So I just feel like this will help redrive that narrative. As a new storyteller, I think there’s a way to tell the truth and still present a more rounded view than what’s been handled—which is overkill.

MH: And you see a throughline in this Black joy quest in public spaces when we think of the Harlem Cultural Festival of 1969. Actually, if you go back to the SOUL! Series first, and then the Harlem Cultural Festival in ’69, and then 1972’s Wattstax in Los Angeles, and Save the Children, then Diana Ross’ incredible rain-soaked Central Park Concert, all the way up to Dave Chappelle’s neo-soul fights neo-liberal gentrification block party: There’s a theme here.

AQT: Yeah, there is, there is definitely a theme here. What’s beautiful about the restoration of this film is that it’s so potent that even when it’s 50 years late, it’s still right on time.

MH: Yes. And I remember after the Sundance premiere, you said, "For as long as it took, the timing of this documentary is, unfortunately, perfect."

AQT: Yeah, literally! You can’t plan a March on Washington, you can’t plan Thriller, you cannot plan YO! MTV Raps. When phenomenons occur, someone has to hit the bullseye on, not only what is needed, but it’s even better when you don’t know that you need it. And that’s what really makes this thing thrive: Nobody knew it was coming; people especially didn’t know that it was coming from me. Creatives often dream of being alley-ooped the ball with five seconds left in the game, like, they dream of this moment. If there’s one thing I’m going to do in this life that might be a paradigm shift, the presentation of righteous Black joy is, indeed, that honor.

MH: And it dispels the myth, and the constant battle we’ve had to fight, of the erasure of the culture. You know, this idea that if Black history is forgotten, it’s the equivalent of being erased.

AQT: Often, people are defensive about it, whenever we bring that up, the instant reaction I hear is, "What, you guys actually think someone’s literally coming with an eraser trying to just burn your history up?"

But I think what’s even more painful in terms of our understanding of racism is that oftentimes people are not even indifferent, but just somewhat blasé about it. Like they’ll say, "I don’t see what the big deal is." It’s a certain denial thing, a slight passive-aggressive thing, that to me is even more painful than the blatant, "My forefathers weren’t castrating people." And I’m like, No, the fact that you deny something’s happening is just as painful as it’d be if you were stringing someone up.

But I just feel like as far as our history is concerned, the reason it’s important to show Black joy is that it lets you know that we existed, that we matter, that we’re not invisible.

MH: Exactly! And that reminds me, like one of the many things that, for example the SOUL! series, and the Harlem Cultural Festival have in common, is that they were considered to be this sort of mythical Black unicorn. And they’re not. And when you see the Summer of Soul, or the SOUL! episodes, but especially Summer of Soul now, you automatically just have to think, Can you imagine how different our lives would have been if we had known? If we had known about the Black Woodstock?

AQT: You just reminded me of something: How strange is it that my three forays into film in the last five years are all soul movies? There's Mr. SOUL!, Pixar’s Soul and now Summer of Soul.

I take it back to the beginning. You know, when I read that Prince book where he talks about how Woodstock defined him as a musician and how it just moved his life, I thought about all the other kids my age that could have had their lives changed by watching this film and how that could have affected their creativity, how that affected how they saw themselves, how that affected how they saw those artists.

Some of those artists managed to become household names despite the erasure. The Staples, B.B. King, Stevie and Sly, those guys managed to overcome and thrive despite not being given the same platform or spotlight to be that great, like their pop rock counterparts. But maybe the powers that be—which I guess hopefully I have a hand in being that power—can redirect the narrative and bring another generation to this genre of music that they otherwise might have not known.

MH: Summer of Soul is so beautiful, Ahmir. I see it as a cultural corrective. Do you want to give a shout-out to your favorite documentary, and would you like to talk about your next one?

AQT: One of the most beautiful things that has occurred is my discovery of my magic and my discovery of the power of manifesting. Even when I was mid-editing this film, I would go on every streaming platform—be it Criterion, Amazon, any of these outlets—looking for music documentaries or things that I’m interested in. And everything that I’ve ever done in my life usually starts with, "Oh man, you know what I wish somebody would do?"—and never fully realizing that I have to be the manifester of my dreams. And so, when I got through this, several projects were green-lit, but the one that I can talk about is what I’m working on now, which is a documentary about the life of Sly Stone.

What I truly want to do is take the same approach, and I know it’s going to be hella easy to lean heavy on tragedy porn. His performance at this festival and Woodstock changed his life immensely in a matter of weeks. What winds up happening is, he becomes a household word and they become America’s band. They’re intersectional, interracial, cousins and brothers and sisters and best friends—like, this is Martin Luther King’s manifestation. They become extremely influential and all they have to do is sink the ball in. And what happens? He throws the ball in the other direction.

And, he’s so genius that even his falling on the sword will change the trajectory of music and the direction of it—but at what price? When we look at the geniuses in our music industry, there’s a common narrative that’s usually tragic. I’ve always been very curious, for those who are declared geniuses, what’s the process? And especially for our Black geniuses. There’s literally no Black genius in music that hasn’t been painted as a tragic figure. From Bird to Ray Charles to Michael Jackson. And Sly represents that. So yes, there’s one story to be told how somebody was so pioneering using their music to break boundaries, but something happened in 1969 and 1970 after Woodstock, and Summer of Soul that changed him, and I want to find out what it was. That’s a common action that’s been happening for 50 years. So, hopefully in providing the outlet to study mental health and that sort of thing that normally Black people don’t speak of, there will be something deeper under that, and I want to investigate—and tell the story of the guy who wrote great music and saved hip-hop, and all those other things. I got my work cut out for me.

MH: Well, I hope there’ll be a little sidebar for the woman you called "the original hype man in the band," Cynthia Robinson.

AQT: Absolutely. They all have unique stories, so he’s not just by himself; it’s everyone.

MH: Her role in music history isn’t celebrated enough. She needs her own documentary.

AQT: Well, I’ll be here to correct that. I’m the one that’s going to revisionize revisionist history.

Melissa Haizlip is a producer, director and writer based in New York. Her film Mr. SOUL! was shortlisted for the 93rd Academy Awards for Best Original Song. The film won the 2021 NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Writing in a Documentary (Television or Motion Picture), the 2020 Critics Choice Documentary Award for Best First Documentary Feature, and the 2018 IDA Doc Award for Best Music Documentary.