In 1994, workers demolishing an old toy shop in Blackburn, Lancashire found three milk churns stuffed with hundreds of spools of film. The negatives—bound for the junkyard but deposited at a local video library that happened, fortuitously, to be on the way—turned out to have been the work of Sagar Mitchell and James Kenyon. Pioneers of early commercial cinema, the Mitchell and Kenyon Film Company roamed the British Isles at the turn of the 20th century and documented everyday life in the Edwardian age.

In 1994, workers demolishing an old toy shop in Blackburn, Lancashire found three milk churns stuffed with hundreds of spools of film. The negatives—bound for the junkyard but deposited at a local video library that happened, fortuitously, to be on the way—turned out to have been the work of Sagar Mitchell and James Kenyon. Pioneers of early commercial cinema, the Mitchell and Kenyon Film Company roamed the British Isles at the turn of the 20th century and documented everyday life in the Edwardian age.

Subsequently restored and preserved by the British Film Institute, the rediscovered trove includes some of the oldest surviving film of professional football. Grainy footage of Manchester United beating Burnley 2-0 at Turf Moor; players walking out onto a snowy pitch for a Rotherham Town home game against Thornhill; an enormous goalkeeper called William “Fatty” Foulkes making acrobatic saves for Sheffield United versus Bury FC. These films, recording the 1902-03 English association football league season, are the earliest proto documentaries of what the world, following the Brazilians, has come to call o jogo bonito, the beautiful game.

The camera likes recording football. Watch the English team give the Nazi salute when they play Germany in 1938 Berlin. See Alfredo Di Stéfano glide past Barcelona in a 1960 clásico. Observe a lesson in samba as Garrincha, Pelé and Vavá dance around Sweden to win the 1958 World Cup.

Little surprise, then, that in our new era of the entranced eyeball, the football documentaries gush as thick as the petrodollars flooding the game. From slick prestige offerings (Amazon’s All or Nothing, each season covering one professional team) to glitzy authorized hagiographies (Amazon’s unfortunately named, 1.1 IMDB-rated The Pogmentary, about the French footballer Paul Pogba; or Netflix’s bland Neymar: The Perfect Chaos); from the football doc as pseudo-analysis of celebrity culture (Manfred Oldenburg’s Kroos, about the elegant German playmaker Toni Kroos, with talking-head philosophers like Robbie Williams and gnomic insights such as “Toni Kroos is trying to control the chaos,” or “Real Madrid make me feel like I have a small penis”) to the football doc as pretentious high art (Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, in which 17 synchronized cameras film the great Zinedine Zidane in extreme close-up, set to the strains of Mogwai and the roars of the crowd, over the course of one match at the Santiago Bernabéu. “It’s incredibly dull,” fulminated film critic Mark Kermode. “I hate football; I hate conceptual art. But there’s something I hate more: conceptual art about football.”); from the fly-on-the-wall story of a hard-luck club in a working-class town fighting for promotion (Netflix’s Sunderland Til’ I Die) to the fly-on-the-wall story of a hard-luck club in a working-class town fighting for promotion, but with new Hollywood owners (FX’s Welcome to Wrexham)—the football documentary has entered its high cornucopian age.

After all, more countries and nation-like entities are members of FIFA than of the UN. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, for instance, had already been playing in FIFA tournaments for 30 years before they were admitted to the United Nations. At the 1966 World Cup in England, the unfancied North Koreans clinched a last-minute equalizer against Chile and knocked out Italy, the favorites. They were only denied a semi-final spot, despite an early three-goal lead in the quarter-final, by the otherworldly genius of Eusebio, arguably Portugal’s greatest footballer, who led one of the greatest comebacks in the history of sport.

This dream run can be relived in Daniel Gordon’s The Game of Their Lives (2002), a documentary about the surviving players on that Korean team and how they won the hearts of the people of Middlesborough, the industrial town they were billeted in. Produced under the watchful eye of a repressive dictatorship, the film reasserts the fundamental truth of a cliché: Sport can sometimes transcend barriers of culture and ideology. For a few weeks at the height of the Cold War, mysterious aliens from North Korea become darlings of factory workers and homemakers in North Yorkshire.

“You see,” says Mr. Nutt the candle dribbler in Terry Pratchett’s Unseen Academicals (2009), “the thing about football is that it is not about football.” Football docs are frequently, as the tags on streaming sites indicate, about scandal, inspiration and excitement. On Netflix, the most popular ones are rousing, feel-good, captivating, nostalgic, heartfelt and emotional. We watch the football documentary in order to cry.

Like the epic or the folk ballad, the football documentary has its own liturgy. We plunge without warning into the heart of a crisis, in medias res, like Hamlet or The Iliad. We circle gradually back to beginnings and prime causes, like The Odyssey, or Star Wars. As in “Greensleeves” or “Matty Groves,” or Richard Thompson’s “1952 Vincent Black Lightning,” insinuations of despair come baked in, ready-made. The narrative demands waves of lunar hysteria that wax and wane, moments of crisis aided by a soaring soundtrack and tasteful slow-motion sequences. Currents of hope and optimism rise, followed by a tragic fall. There is prayer and redemption. The underdog triumphs.

A remarkable version of this arrangement beats at the heart of Mike Brett and Steve Jamison’s understated Next Goal Wins (2014), about the “world’s worst football team,” American Samoa, and their desire to improve after a 31-0 loss to Australia, the worst result in the history of international football. In the wake of global shame, a gruff Dutchman called Thomas Rongen is recruited to coach the team as they prepare for the 2014 World Cup qualifiers. Rongen, an atheist who is recovering from a terrible personal tragedy, is drawn closer to his players and to the island’s spiritual resonances. When the team wins its first international match, he breaks down.

What unfolds is an acute portrait of the economic and cultural mores of a tiny, unincorporated territory of the United States. Prospects are so bleak that most young people can only look forward to joining the American army. Many of the players are on leave between deployments. Jaiyah Saelua, a hard-tackling defender who is faʻafafine (literally “in the manner of woman,” a third gender in Polynesian society dating back to matriarchal rule centuries before European contact), emerges as the soul and star of the team. In the process, she becomes the first trans woman to play in a FIFA World Cup qualifier. Nicky Salapu, the goalkeeper on the receiving end of 31 goals, has recurring nightmares; he returns, to exorcise his demons. I bawled my eyes out.

Many of these films belong to that sub-genre of the sports documentary as cultural criticism. The best examples—Fire in Babylon, ostensibly about the great West Indian cricket team of the ’70s, but, in the vein of C.L.R. James’ Beyond A Boundary, as much about racism and colonization in the Caribbean; or Hoop Dreams, the story of two high-school basketball players that functions as a reflection on race, class and education in modern America—use a player, team or game to talk about wider socio-political subtexts. Asif Kapadia’s Diego Maradona (2019) uses rare archival footage and an immersive sound design to highlight the injustices of geography in Italian culture, the influence of crime and politics on its sport, how the greatest footballer in the world makes a whole city dream again, and why he undoes himself along the way.

Sucked into the maelstrom of Naples in the 1980s, where the slime of corruption and Camorra oozed frequently into football, Maradona’s turbulence ebbed and flowed with the tumults of an ancient city and the ecstatic arches of its sporting despair. No wonder Napoli still reveres him. To make room for the Argentine, it has evicted St. Paul himself—the old San Paolo stadium is now the Stadio Diego Armando Maradona.

Maradona belongs to everyone. Emir Kusturica’s Maradona by Kusturica (2008) takes the footballer out of Naples and contextualises him as world-historical phenomenon, a totem for the Global South. Maradona joins famous musicians to sing songs about himself, addresses rallies for leftist politicians, and gleefully describes his infamous Hand of God goal in the 1986 World Cup as the thrill of pickpocketing Englishmen’s wallets in the aftermath of the Falklands War.

Soccer, wrote Eduardo Galeano, is the “ritual sublimation of war.” Nowhere is this more evident than in Vice’s 2012 documentary about “football’s most dangerous rivalry,” the fear and loathing between fans of the Old Firm, the collective name for Glasgow’s two big football clubs—Celtics, the club of Irish Catholic immigrants, and Rangers, who refused to sign Catholic players till 1989. With hardly any clips of actual football, Rivals: Rangers and Celtics is a sociology of nationalism, tribal hatred, and Glasgow’s sectarian divide. There are brutal skirmishes, incredibly offensive songs (Rangers fans have ditties about Irish famines, Celtic fans about IRA killings), and interviews with the only Muslim member of the far-right English Defence League, a Rangers fan who has been banned from football matches for singing “Dundee, Hamilton, fuck the Pope and the Vatican.”

From homophobia and hooliganism to the geopolitical ramifications of sport, the football documentary trades in shadow and fog. ESPN’s exceptional The Two Escobars (directed by Jeff and Michael Zimbalist; 2010) focuses on the fatal nexus of crime, sport and politics and the rise of narcosoccer in Colombia. It narrates the dramatic rise and fall of Colombian football and how its fortunes are tied to Colombia’s notorious drug cartels by linking the stories of national team captain Andrés and drug lord Pablo, who share similar tragic fates and the same last name.

“The mafia runs an illegal business,” explains Jaime Gaviria, cousin and confidant to Pablo Escobar. “The only way to legalize their earnings is through money laundering. And soccer moves millions of dollars.” From Cali to Medellin, all the cartels are in the business of soccer.

In December 1993, Pablo Escobar was gunned down on the rooftops of Medellin. Some months later, after Andrés returned from the World Cup having scored an own goal against the USA, he was shot dead in a Medellin parking lot. Their lives and deaths circumscribe Colombian football.

“When Pablo died,” his dreaded lieutenant Popeye deadpans to the camera, “drug dealers learned a lesson: It’s too dangerous to get involved in soccer.” Soon, narcosoccer transitions into a more transnational and abstract financial instrument embedded within the circuits of global capital.

“The history of soccer,” Galeano writes in Soccer in Sun and Shadow, “is a sad voyage from beauty to duty.” In our new age of soccer as Special Economic Zone—petrosoccer, fossil-fuel football—a sport owned by magnates, gamblers, and oligarchs demands the undistracted flow of coin. “The days are long gone when the most important clubs…belonged to the fans and the players. Today clubs are corporations that move fortunes to hire players and sell spectacles…tricking the state, fooling the public, and violating labor rights and every other right.”

According to a report in The Guardian, nearly 7,000 migrant workers from the Indian sub-continent have already died from poor working conditions and increasing temperatures since the 2022 World Cup was, in a haze of corruption and bribery, awarded to Qatar. This is the latest, as Jean-Louis Perez’s Planet FIFA (2016) suggests, in FIFA’s long history of systemic corruption and neocolonialism.

Why is FIFA headquartered in Switzerland? The film points to Switzerland’s love of political neutrality and opaque banking. This suits soccer’s governing body, which wishes to be at the center of both Europe—in Qatar, as in all other World Cups, over a third of the slots are for European teams, despite Europe representing less than a tenth of the world’s population—and the global financial system. On camera, the head of a nonprofit seeking to advance commercial transparency compares FIFA to the mafia.

FIFA imposes its own set of rules before awarding tournaments to host countries. “No organization besides FIFA,” its former communications director remarks, “has the means to suspend the judicial and legal statutes of entire nations.” When their country hosted the World Cup in 2014, Brazilian taxpayers ended up paying $11 billion. FIFA insisted they build “at least” eight new stadiums. The Arena da Amazônia in far-flung Manaus cost $230 million and hosted four matches. It is now used for birthdays and weddings.

“There is no multinational corporation,” lamented Galeano, “that enjoys greater impunity than FIFA, the association of professional clubs.” Although Planet FIFA ends with many of FIFA’s presiding spirits in jail and banned from the game, the prognosis is bleak. Today, FIFA simply spreads out the kickbacks with greater diversity (“One of the great strengths of the world is indeed its very diversity,” the current head of FIFA wrote recently, in defense of Qatar’s homophobic laws, “and if inclusion means anything, it means having respect for that diversity”).

The Qatar World Cup, in winter rather than midsummer, is the first climate-change cup. Tainted by issues of corruption and human rights abuses, and accessible only to those who can afford exorbitant all-inclusive packages, this is a World Cup for the wealthy. It is also the most militarised, involving RAF jets, international military specialists, the DroneHunter attack system, and NATO handling chemical, biological and nuclear threats. Qatar 2022, wrote The Guardian’s Barney Ronay, is “a vast geopolitical security operation.”

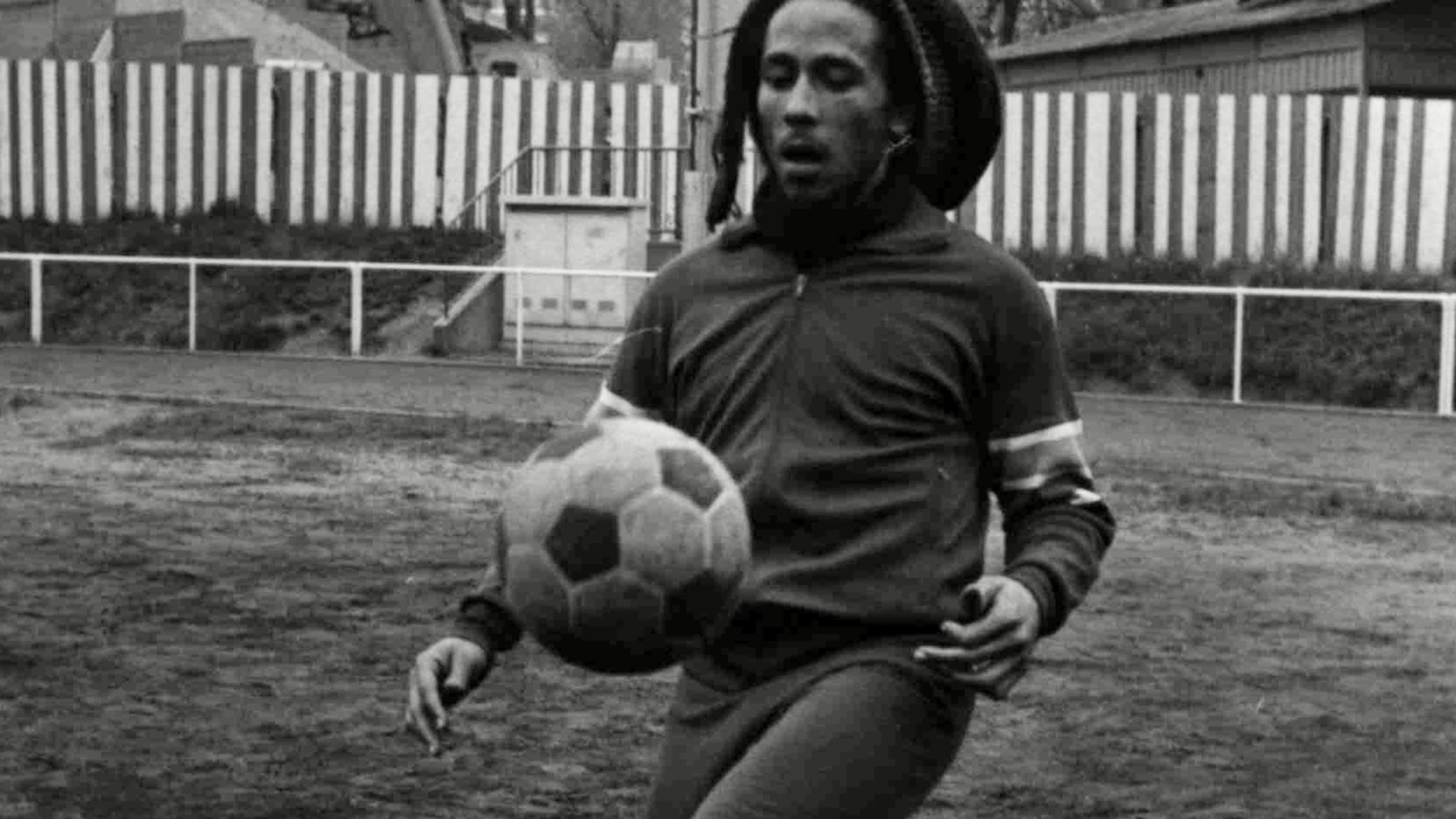

Football may have bourgeois origins and elite petrostate sports-washing aspirations, but, ultimately, its soul belongs to the working classes. As Bob Marley says in Legacy: Rhythm of the Game (Marcus McDougald; 2020), a documentary tone poem examining his life-long relationship with the game, “Football is freedom.”

It is the game they play in Misha Kumar’s Maithaanam (2022), about the football-crazy Indian state of Kerala, where a tiny village called Pozhiyoor produces state-level players at breakneck speed; 90-year-old coaches for over 50 years for free; and a terminally ill woman’s dying wish is to go see the Kerala Blasters play.

It is the reason Sunderland is deserted, “but for a solitary policeman trudging a lonely beat,” on May 5, 1973, in Meanwhile Back in Sunderland, an ITV vox-pop recording a day in the life of the port city, when their team, rank outsiders, won the FA Cup.

It is what comforts Japan when they win the Women’s World Cup soon after a devastating earthquake and tsunami; it helps rebuild Rwanda torn apart by genocide (Amazon’s This Is Football, 2019).

“Colombia’s problem,” Vice-President Humberto de la Calle despaired after the assassination of Andrés Escobar, “is that football is no longer a sport, it seems, but a matter of life and death.” Bill Shankly, the legendary manager of Liverpool FC, would have disagreed: “Some people believe football is a matter of life and death,” he once said. “I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.”

Sudipto Sanyal is a writer in Kolkata, which, as everyone knows, is the footballing capital of both Brazil and Argentina. He would love to see a) Cameroon as world champions, and b) India qualify for the World Cup, preferably before he dies.