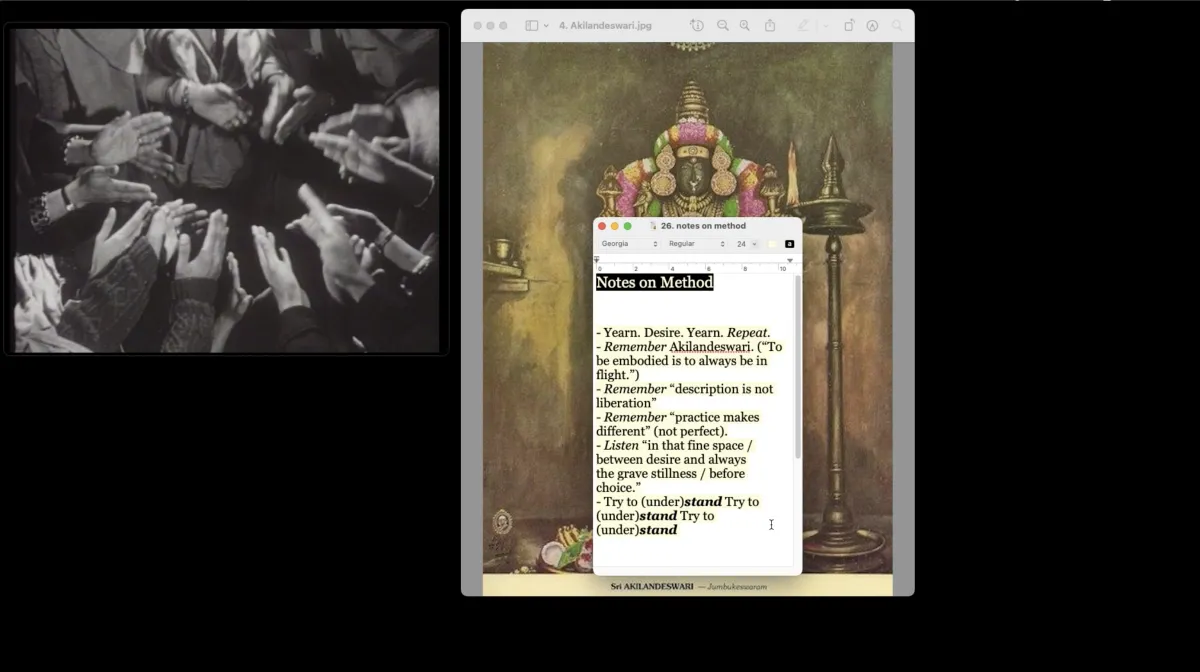

Screenshot from “Yearning as method in programming,” a performance lecture commissioned by the Independent Cinema Office in 2023. Courtesy of Jemma Desai.

Over the years, Jemma Desai’s writing, programming, research, and practice have intersected with institutional critique. Through investigating film institutions’ languages of colonialism, she’s brought renewed attention to hierarchies, systems, words, and ways of relating that are often taken for granted. Born out of a combination of rigorous research, firsthand experience working in institutions such as the British Council and the BFI, as well as testimonies by other arts workers, This Work Isn’t for Us (first self-published in 2020) was a crucially timely study of the fundamental problems plaguing institutional initiatives surrounding diversity and inclusion that often end up reproducing existing power structures. Desai is a current Ph.D. candidate at the Central School of Speech and Drama, a collaborator with BlackStar Film Festival, and a somatic facilitator. She will be a keynote speaker at Getting Real ’24 as well as the curator of the 2025 Flaherty Seminar.

Meeting Jemma in a London cafe on a breezy Thursday afternoon, I took the opportunity to delve into questions surrounding the function, structure, and politics of film festivals that have been on the minds of many, including myself, in the past months.

DOCUMENTARY: From my limited experience, what I valued most about festivals was the feeling of community with other up-and-coming critics from around the world. Some of these critic/friends attended Berlinale this year, and some decided to boycott the festival. I know that some who did go have been as indignant as those who didn’t, if not more so, with added feelings of guilt. These are younger people trying to start a career in an increasingly precarious field. The supply-and-demand logic applies not only to films and filmmakers, it also puts enormous pressure on critics and programmers.

JEMMA DESAI: Let’s focus on the fictions inside the work we do: that somehow getting to go to a festival is a great privilege, when the reality is that it is for many a great burden, a tax to participate in an unfair ecosystem. Many are spending their own money, at great financial risk. Nobody wants to talk about this ever-present truth—there is shame in admitting a lack of resources in a system that thrives on elite access. I’ve been there, too, putting myself financially at risk just to be part of the conversation, to watch something months before it comes out before it is somehow sullied by mass marketing.

The industry is built on the pretense that this is sustainable. What if the top festival directors were more honest about how little freedom they have to allow for freedom of expression? What might be revealed that we could work toward changing? And at the bottom, what might be more evident if we displayed less gratitude for the crumbs we are offered as precarious artists, programmers, and invited guests? Right now, there feels like a lot of division and judgment. The problem is not the request for new terms of engagement but the facade itself. Now is a moment when we might reveal what is underneath that facade. It feels important that happens for change to take place.

D: Berlinale’s attitude to discussions around the genocide being carried out in Palestine has brought forth a question that’s more complex than it appears at first: Who are film festivals really for?

JD: The answer to this question always seems to be “for audiences,” for “others.” Whenever people put together a festival, they implicitly endorse a form of relation that centralizes the film and the filmmaker, putting them on a higher plane than the mortal audience. But at prestige festivals like Berlinale, audiences are not really “mortal”—they are the industry. So, festivals become about critics, buyers, and people who have status or means to be there. There may still be a general audience, but a quite rarefied one that can get there first. Recent events at festivals show very clearly that there are many fictions inside the supposedly neutral spaces [in which] we circulate and celebrate film, and the fictions about audience are central to them.

Large, state-funded festivals replicate state interests in culture. Necessarily, they become geopolitical demonstrations of power. Necessarily, this must be hidden or disavowed through “civilizational or universalist politics.” We’ve seen that in the history of European festivals, from the fascist roots of the Venice Film Festival to the progressive establishment of the Cannes Film Festival in response (set up with the support of the Americans and the British). Yet now, in both festivals, who gets a pavilion? How much money and how many films come from different regions of the world? At the smaller end, and even in the margins of big festivals, events can really be a form of connection, but the shadow of these forms of relating remains.

D: Elsewhere, you’ve talked about the film industry as not being the most conducive environment to creating a community. As filmmakers and critics, most of us have to constantly compete with each other for funding, grants, opportunities, etc.

JD: There’s scarcity, so even if you don’t want to compete, you’re put in a position to have to. Plus, it’s also a hierarchical industry that is good at hiding or fetishizing the accrual of privilege. It’s hard to build a community on this erratic, asymmetric base that’s not values-driven. Community is built from shared value systems and shared needs. You can accrue power from taking certain positions within the industry, but you’ll lose power if you actually stand for the integrity of those positions. So, making something about political resistance and actually supporting political resistance are two very different things. You’ll get very different rewards for holding those two different positions.

D: Many people aim for networking rather than building community. The environment feels more suited to opportunism and competition than anything else.

JD: In a hostile, transactional space, it makes sense to protect yourself through transactional relating rather than mutuality. Festivals are formulaic spaces with a certain kind of repetition, a certain practiced mode of relating that you need to get good at if you want to succeed. This then results in a certain kind of reality. I’ve often found community with people who make themselves quite vulnerable by telling the truth about what they’re facing, and often isolated myself by sharing what I am facing.

We’re so practiced in this transactional way of relating that it imbues much of our work without us even realizing. If we want this to change, we not only need to create new spaces but also need to practice new things in them over and over again. That’s why I say abolish the festival. They take up so much space. They colonize our imaginations and relationships. There are other ways that we could give and receive our work, ways we can’t even imagine right now.

D: You’ve often emphasized that these values, behaviors, and patterns are ingrained in the systems and structures that underlie spaces like festivals. It’s important to emphasize this fact and not fall into a moralistic conversation or judgment of individuals.

JD: When I think about structures, I think about structures of relating and feeling, and of course, historical structures like capitalism and colonialism. But I think about the structure of film festivals through language because my experience of the film festival was unlocked through looking at the colonial origins and nature of words like “submission.” I realized my relationship with filmmakers is formed by the fact that I’m here for them to “submit” to.

D: I’d say there is a dialectic between capitalism and imperialism as systems of economic and political domination and the language that they shape and produce. In return, that language ideologically reinforces them every day. As you said, enough repetition makes the existing state of things seem natural. Berlinale’s resistance to even offer verbal concessions about what’s happening in Palestine is revealing something about the “official” institutions of culture under capitalism. It’s having a radicalizing effect by shattering a lot of illusions about them.

JD: I see this moment as a clarifying moment of attention. One where we might let go of the fictions I mentioned earlier. As Angela Davis says, radical simply means “grasping things at the root.” The root is power: who has it, wields it, and gets to set the terms of the narrative around it. This is important on a geopolitical stage as well as in the structures of film festivals. I want to acknowledge that one is infinitely more important than the other, yet I feel so strongly that we need to leave behind—in all aspects of our living—ways of relating that are complicit in the genocide we are watching unfold.

Whatever structure we build around art will reflect the world in which we live, with all its inequalities and power dynamics. When we still want a structure that clearly cannot recognize the sovereignty of Palestinians because of the logic in which it exists, then it’s better that it says nothing [about what’s happening]. To me, this has been a form of peeling away. We have to remember this moment because it will be quickly covered up. It’s just a fact that this is not for everyone, and it’s never been for everyone. We just chose to ignore that because there was enough of something there for us individually

D: It’s a point of crisis that’s forcefully uncovering things that were normally too inconvenient to acknowledge. On a more positive note, how have you approached alternative avenues of building community?

JD: I am interested in learning skills that make group work more possible. This is something that many of us who’ve worked in institutions for a long time, myself included, are not very practiced in. I want to live what I learn, to practice it, not just say or think it. I am interested in processes and people. I want to make new realities with others. I want to create an alternative way of making and being together because I just don’t believe in the idea of individually programming or individually trying to change things anymore. So, I have been investing more in performance and somatics and attendant organizing and writing work, which helps me think about story and image in ways I find hard in normative programming.

I often think about Ruth Wilson Gilmore talking about abolition as presence, not absence, of investing in practices that would make harmful structures irrelevant. I want to invest in this idea of group formations and group work and understand what is possible in that container. Maybe nothing is possible, but I want to know why.

And having said all of this, after the last few months, my hope is waning. I will always want to make and do things with other people. But the idea that this is where I will earn my living from, that this work will love me back, that the way that I want to work can be actualized… it feels clear to me that so much else has to change. I’m very interested in what you said about people who are suddenly more attuned to what is wrong and in supporting spaces where we can bring this energy to something material. There have to be so many of us invested in letting go of old systems, but even at this moment, I’m not sure that most are ready to do this; I hope this changes.

D: What is the significance of “Yearning,” the theme of Flaherty 2025?

JD: Again, this has shifted so fundamentally for me in the past few months. Perhaps the season of yearning is over. I hope this is a moment of action, of transition. In birth, the moment of transition is when every person says, “I can’t do it,” and then the baby comes anyway. I think about holding people through the inevitable transition rather than yearning for them to get to that point because, at this moment, I am struggling with the possibility that making, giving, and receiving images leads us to a collective space. I don’t know what to do with yearning during a live-streamed genocide. Black feminist Lola Olufemi recently made a differentiation between hope and determination in this moment. Holding, gathering, offering, and trust feel like the skills that are necessary for this season of determination when hope is weary.

Arta Barzanji is a London-based Iranian filmmaker, critic, and lecturer. He has written for publications including MUBI Notebook, Sabzian, and photogėnie. His current film project is the documentary Unfinished: Kamran Shirdel.