IDA Career Achievement Award: Roger Ross Williams, Excavator of America's Hidden Truths

Roger Ross Williams' list of accolades is mind-blowing. In 2010, he became the first Black director to win an Academy Award, for Best Documentary Short Subject. The film, Music by Prudence—which followed a troupe of musicians with disabilities in Zimbabwe—was his first documentary as a director.

Williams followed that success with God Loves Uganda; the Academy Award-nominated, and Emmy and Sundance Film Festival award-winning Life, Animated; the Emmy Award-nominated Traveling While Black; and The Apollo, which won the 2020 Emmy for Outstanding Directing.

This past year he produced and directed the highly acclaimed Netflix series High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America. He is currently in pre-production on the TV series documentary version of Nikole Hannah-Jones’ The 1619 Project.

Williams is the 2021 IDA Career Achievement Award honoree. His work is defined by his passion for excavating the hidden stories behind key historical moments. Though this often brings him into confrontation with America’s racist origins, he is far from a masochist. Rather, he is driven to help audiences learn how to do better by embracing unvarnished truths.

Doing better, particularly for the next generation of BIPOC filmmakers, is a high priority for Williams. In 2016, he was elected to the Board of Governors of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, where he has advocated for diversifying its membership. In 2019, he co-founded One Story Up, a production house that provides opportunities to filmmakers from underrepresented communities who desire to create documentary work.

Documentary spoke with Williams about the inspirations for his career, learning from the past, embracing pain, and paying his blessings forward.

DOCUMENTARY: Have you experienced any mishaps while filming?

ROGER ROSS WILLIAMS: During God Loves Uganda, someone told the pastors I was filming that I was gay. They surrounded me with their German Shepherds and I thought they were going to kill me. But then they pulled out an article about my Oscar and told me, "We're not going to kill you because you're too high-profile. But we're gonna cure you." So they all laid hands on me and started praying for me.

D: This feels ridiculous to ask, but is that not the most intense thing you’ve ever experienced?

RRW: Yes. But on a certain level that was what I was looking for. I wanted to go to the scariest place in the world, where people were persecuted because of religion.

D: Why?

RRW: I grew up in the Black church singing in the choir. I was the illegitimate child of a minister at another church. So for me, going there was partly dealing with my own issues around religion and homosexuality.

D: Did you know you were gay when you were growing up?

RRW: Yes, I knew. But when you’re part of a homophobic church, you're in denial about it. And it's very tough to deal with that because you feel this incredible sense of rejection. And how do you deal with that as a kid?

That’s why I was drawn to Prudence. She was completely thrown away by her family and community. She didn't think she was human, but she overcame all of that through her gift for music. That really spoke to me. As soon as I watched the mini-DVD that she sent me of her singing, I started crying and was like, "This is it. I'm quitting my job at CNN and I'm going to Zimbabwe."

D: Had you been to Africa before that?

RRW: No. But when I landed in Zimbabwe, I told Prudence, "Our fates are forever intertwined. We are a team, and we're about to take this incredible journey together." And boy did we.

D: This was your first film. Were you afraid?

RRW: You know, I had just ended a seven-year-long relationship and I was not happy with working for the man or in mainstream media. So for me it was like, "In life, you have to throw everything to the wind and take these big risks in order to make a difference and get ahead." So I just dove in.

I’ll admit that it was crazy to get on a plane to a country that was ruled by a maniacal dictator in the midst of a brutal, violent election, where journalism was illegal.

D: How did you get your cameras in?

RRW: I had to sneak them in through Botswana. They were hidden under the seats and equipment of the disabled kids I was working with. We got past the border agents because they wouldn't touch a disabled child. They believed that disabled people were cursed and that if they touched one, they’d have a disabled child too.

That was what was so powerful about making Music by Prudence. Despite everything that life handed them, those kids woke up everyday with such joy. They were incredibly inspiring, and helped me get over my own unconscious prejudices toward people who are differently abled. That experience also set me up to make Life, Animated because I was able to see Owen [Suskind] as someone with a great gift, as opposed to someone with a great deficit.

D: Have you been around to see how your films affect the lives of the people you work with?

RRW: Oh, yeah. The reception that Music by Prudence got in Zimbabwe was mind-blowing. Prudence changed the way the nation thought about people with disabilities. When she got off the plane after coming home from the Oscars, they put her in an open-top Rolls Royce and paraded her through Harare, she made a speech to both political parties, and there were editorials in the newspapers saying that Zimbabwe needed to reexamine the way it treated people with disabilities.

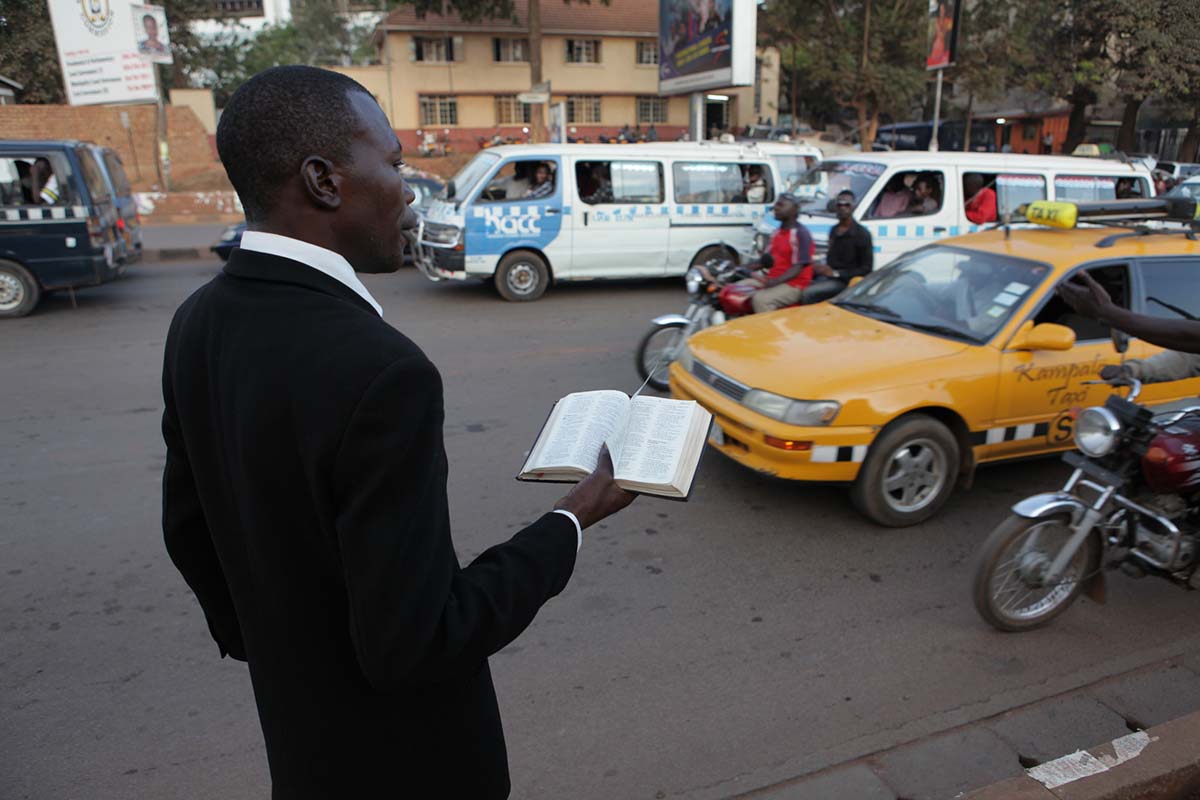

God Loves Uganda also had an amazing effect. It really opened people's eyes to the incredibly destructive hate that American evangelicals are spreading on the continent, and how it results in death for the LGBTQ community in Uganda and beyond. Ford Foundation sent me on a tour of Africa that started in Nigeria. A few screenings brought pastors and members of the LGBTQ community together to talk for the first time ever. Some of those conversations were very heated.

At a big theater in Malawi, a woman stood up and said, "I'm married. I have two children. And I've been living a lie and you forced me to live this lie. And I am here today with my girlfriend." The whole thing was being broadcast on national radio. After that, gay people started to come down the aisle while saying, "I am living a lie. I'm gay." It was Malawi’s first mass coming-out ceremony in history.

D: Watching High on the Hog was an incredibly emotional experience for me. How did you tap into that feeling of transcendence?

RRW: I told the crew and team of producers that we had to summon the ancestors and take a spiritual journey; to take our time and feel all the feelings, including the pain, that we have been holding inside. A lot of my work is about bringing those deeply felt feelings that you don't want to face to the surface and experiencing them.

With High on the Hog, you thought you were seeing a series about food, like any other series, but it was actually a deeply emotional journey about the pain we’ve suffered and what food and gathering together means. It was the same feeling with Traveling While Black: tapping into a truth and depth that reveals something extraordinary.

D: What I tapped into was, "Black people are more than descendants of enslaved Africans; we are the creators of this country’s culture."

RRW: Absolutely. That message is also part of the 1619 Project docuseries that I’m working on with Nikole Hannah-Jones and Oprah for Hulu. We’re examining who has upheld America’s values.

D: Black people?

RRW: Yes. Because Black people are the keepers of democracy. We’ve fought for democracy because we had to, from the minute that we were enslaved—because the hypocrisy of white America has refused to see all that it has done

That’s a major point in the work I’m creating for Netflix with Ibram X. Kendi. It’s going to be three projects based on his books: Stamped from the Beginning, Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You, and Antiracist Baby. One of the people we look at is Thomas Jefferson. Here’s a guy who's writing the Declaration of Independence, but the person who’s serving him is James Hemmings; the brother of Sally Hemmings—the woman he repeatedly raped and had all these children with. And to keep her brother enslaved, Jefferson took him down to Virgina across the Mason Dixon Line every six months, because if he hadn't, James would’ve been granted his freedom.

D: It doesn’t sound so romantic when you consider that this might have been another reason why Sally never ran away.

RRW: Exactly. I want America to face its past and what that has turned us into. Because we cannot heal until we face the truth. A lot of people do not want to face the truth, hence the backlash against critical race theory and Nikole Hannah-Jones’s 1619 Project.

D: Educating people feels imperative to you.

RRW: So much! Everything I do is about stating the facts that I didn't learn in school. That’s where High on the Hog stemmed from: wanting to right the wrongs of buried history and to educate people. I hope that it opens people’s eyes and makes a difference. I think it will, because truth is power and once it’s out there, you can’t hide from it.

D: I appreciate that you don’t water things down so that white people come away feeling okay about racism.

RRW: I can't sugarcoat things. While I was interviewing a group of Black women historians—who work on the legacy of slavery in this country—for Stamped from the Beginning, they told me, "We have to do this because this is the reality we live in. If we don’t do this work, who else will?" It’s the same for me. This is about self-preservation.

D: Is it painful?

RRW: It hurts in the same way as it did when I stood in church as a boy and absorbed all of the hatred that was against me. But I tell myself that I can translate that pain for the world. When we were filming in Charleston, Mississippi, we found out that if Black people were walking around during the daytime instead of picking cotton, they’d get killed. That was painful for the entire crew, but it was so important that we take in the harsh realities that Black slaves and sharecroppers experienced, so that we could translate it to the screen.

D: You started your career as a journalist, which is the same thing as being a storyteller. Was that something you planned for?

RRW: No. It just kind of happened for me. I was bullied a lot in school as a kid. Our house got redeveloped and we moved to a white suburb. So I got attacked and called the N-word by the white kids for being Black, and got picked on by the Black kids for living in a white community and being gay. I was attacked from all sides. So I retreated into my room—into my own fantasy world where I created situations. I’d make little dolls and they would interact and have dialogue.

I actually thought I’d be an architect because I loved designing things. I would draw architectural renderings of houses and imagine the people who’d live in them and create narratives around that. I didn't really have a lot of friends because I was too afraid to go outside. Some summers I wouldn’t leave my room except to use the bathroom or go to the store with my mom.

It seemed like that was never going to end. I used to think, "Am I ever going to be free?" But it really gave me an incredible imagination and developed my storytelling chops. I was also severely dyslexic, so I learned to memorize everything visually. I was incredibly observant because of that, which helped when I became a journalist.

D: How do you withstand the trauma?

RRW: I think this is where my training as a journalist helps because I learned to sit in a chair, ask questions, and not react. For example, I was interviewing a pastor in Mississippi who was like, "Gay people are worse than animals. They're not human. They need to be eliminated." But I was able to sit there and be like, "Yeah?"

I can only do that because I have a mission to enlighten people around the world so that they know about the injustices that are going on. And I love to do that. So I’m able to just absorb what’s happening.

D: Is there a pay-off?

RRW: That comes out later when you're in the editing room using all the cinematic tools. When I cut a great scene with music and everything is working—I sit back, watch it, and cry. That’s a magic moment!

D: Do you look at your position on the Board of Governors of the Academy as a step forward?

RRW: As the first African American to win an Oscar for directing, I can't rest on those laurels. I have to pay it forward and use everything at my disposal to allow opportunities for people like me. That's my mission in life because I didn't have those opportunities and I want to change the game. I’ve got to bring as many people as I can to the table, introduce them to the buyers and to the streamers, and vouch for them.

When I walked into the boardroom for the first time, I was intimidated but I knew I couldn’t take my seat for granted. I told myself, "Now that I am part of the establishment, I have to kick the door open for others to have a seat at the table." That's actually why I ran for my seat and that’s what I've been doing: diversifying the documentary branch of the Academy, which is now its most diverse branch. We're the first to go from non-gender parity to gender parity. I’ve also recruited members from Africa and South America, and helped build a huge international membership.

D: What’s the end goal?

RRW: All of this work is about owning and telling and profiting off of our own stories. For so long, everyone else told them and made money off of us without investing into our communities. If I leave behind any type of legacy, I want it to be that I gave opportunities to BIPOC storytellers and kicked down the doors.

D: How important is it for filmmakers to learn how to produce their own work?

RRW: It's essential. I know that a lot of people of color have been stuck making reality television because those are jobs available to them. But all of them have passion projects and rich stories that they want to tell. I’ve had many people tell me stories of their communities and I’ll go to buyers and say, "I want to give this filmmaker a break. I will guide them. Sit in the edit room, go on shoots, or even co-direct with them. Whatever it takes to get this made. Because their stories are important and we're richer as a culture for hearing them."

I do all of this because it really is an honor to serve my community. When I was a kid, I didn't have a community. I was alone in my room. But now I have multiple communities that love and support me and I want to love and support them back.

D: I'm grateful that you came out of your room to play with us.

Juan Michael Porter II is an award-winning staff writer of TheBody.com, and has contributed to PBS’ American Masters, San Francisco Chronicle, Christian Science Monitor, NY Observer, American Theatre, TDF Stages and Time Out NY. He is a National Critics Institute and Poynter Power of Diverse Voices Fellow.