“Sometimes the Past Is a Snake”: Tatiana Fuentes Sadowski on the Legacy of the Rubber Trade in ‘The Memory of Butterflies’

Courtesy of Berlinale

“I’ve received a charge. I’m speaking of a transmission, of receiving a message, perhaps formulated long ago, extended to whoever could receive it.”

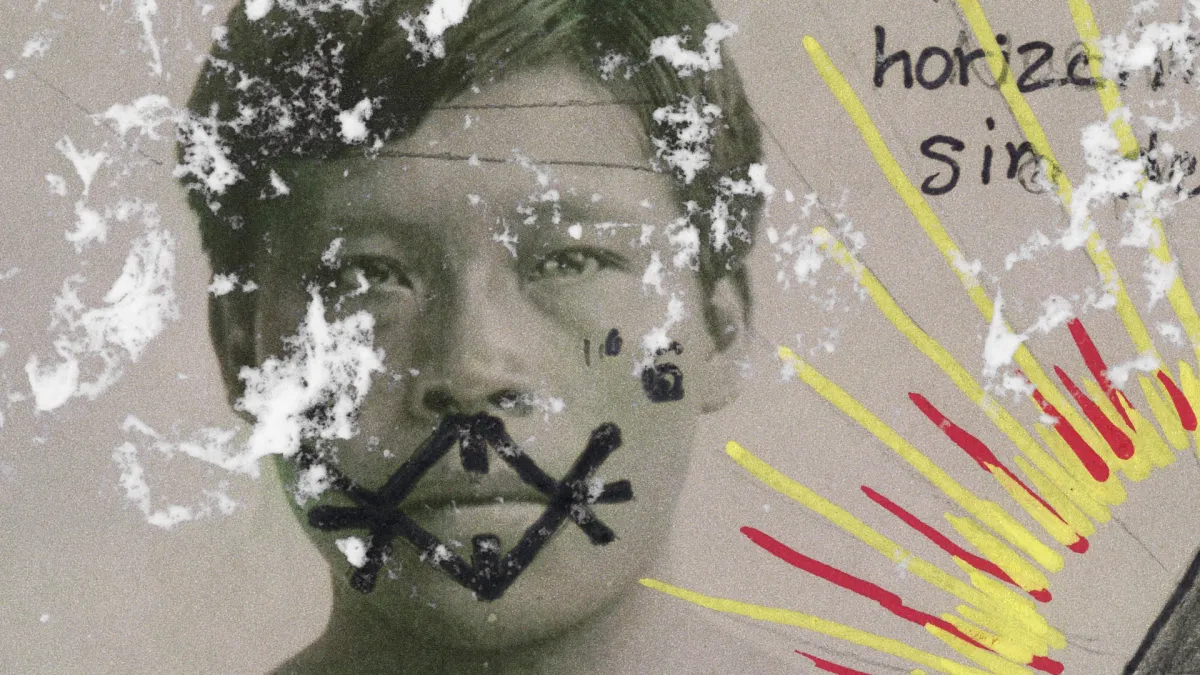

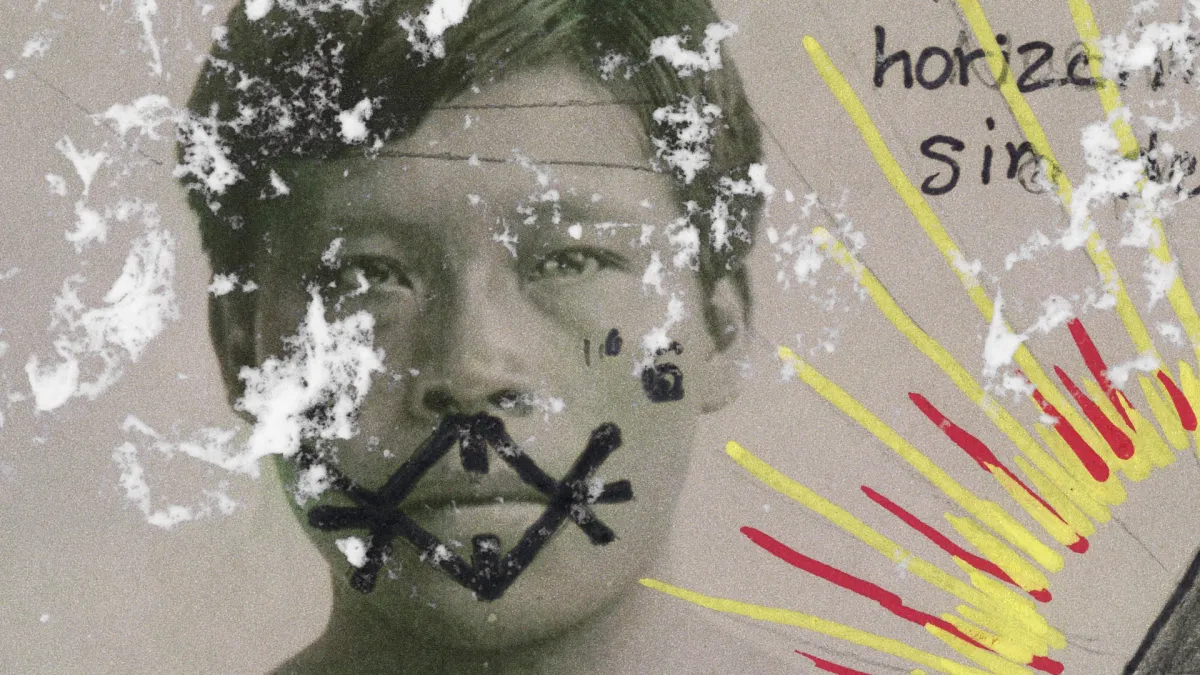

Close to the start of her hypnotic documentary The Memory of Butterflies, director Tatiana Fuentes Sadowski describes the moment that inspired the film. While looking through a selection of propaganda images taken by a company operating in the Amazon during the late 19th-century rubber boom, Sadowski came across a posed portrait of two young Indigenous men. In the image, the pair stands hand in hand dressed in Western clothes, stiff suits and ties, gazing at the camera with solemn, unreadable expressions. The photograph came with little information, just a date and location (London, 1911), and two names: Omarino and Aredomi.

This photograph became a point of obsession for the filmmaker. Having received the transmission, she couldn’t look away. “Each time I return to their photograph, I get the same feeling,” Sadowski says in the film. “Omarino and Aredomi are observing me. Their photo calls me, questions me.” To find more information about the two young men, Sadowski began searching in colonial archives, predominately in Europe. Through this research, Sadowski came across turn-of-the-century propaganda films, which portrayed the rubber trade as an industrial miracle, and celebrated the rubber tappers as “champion[s] of the Amazon… who turned Hevea latex into gold.” She also came across the notebooks of Roger Casement, the Irish diplomat and campaigner, whose reports from Peru in the 1910s exposed genocidal human rights abuses perpetrated by rubber companies against Indigenous people in the Putumayo. Casement had also arranged to bring Omarino and Aredomi to London in 1911, essentially so they could be presented as propaganda against the rubber industry. Piecing together these fragments, Sadowski began to construct a film that uses the partial, semi-obscured story of Omarino and Aredomi as a gateway into a larger examination of colonial history and culpability.

In The Memory of Butterflies, Sadowski mixes this colonial-era archive with present-day Super 8 footage charting her own journey into the Amazon and meetings with Indigenous communities with ancestral ties to Omarino and Aredomi. The film is captivatingly gorgeous, with flickering images and eerie sound design (by Félix Blume), but it’s also deeply contemplative. In a gently poetic voiceover, Sadowski tentatively speculates on the thoughts and feelings of these two young men, and gestures towards the harrowing cruelties carried against Indigenous people during the rubber trade. As her gaze turns further towards the present, Sadowski also acknowledges a close connection to this material—her son is directly descended from rubber barons through his father—and this personal tie adds a further complexity to the filmmaker’s sense of responsibility to this story. In its dazzling experimental editing (the film was co-edited by Sadowski with Fernanda Bonilla and Elizabeth Landesberg), The Memory of Butterflies deconstructs the conventions of historical documentary, questioning the ethical complications of using colonial footage, produced under coercive and exploitative conditions. With its flickering images, bold use of color, and repetitious cutting, the film offers a vision of history as unstable and circular, forever repeating itself, morphing and warping in the light of new interpretations.

Documentary spoke to Sadowski shortly after the film’s premiere at the Berlinale, where the documentary jury awarded the film a special mention, about the ethics of colonial archive, cinematic speculation, and sound as a threshold. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: How did you come across this image of Omarino and Aredomi, and how exactly did that then spark the film?

TATIANA FUENTES SADOWSKI: I came across this photograph in Iquitos in 2015. At this time, an album of propaganda photographs taken by Casa Arana [a rubber company run by the Peruvian magnate Julio Cesar Arana] had recently surfaced. Inside this album, there was this image of Omarino and Aredomi, and I was immediately touched by the strength of their gaze. In the film, there is this motif of the past coming back again and again, and I also experienced this sensation happening in real life with the photograph. I began to look into Silvino Santos, a very well-known Portuguese-Brazilian filmmaker who made early films in the Amazon. After that, I went into the colonial archives from this time. These kinds of images I call brother or sibling images, because even though these colonial images were not directly related to Casa Arana or Omarino and Aredomi, they were created for the same purpose as that photograph. There are not many images of this time in Peru. There are more images in Ireland, because of the work of Roger Casement, and also in England and France, because these were the countries that were commissioning films about these faraway places at that time.

D: The testimony of Roger Casement, who recorded conditions in the Putumayo, features heavily in the film. But you also say in your narration that Casement’s writing is “an opaque doorway, into what he decided to let us know, and what he decided to forget.” How did you begin to address the gaps in his writing?

TFS: Casement had so many notes about Omarino and Aredomi, but all of them are quite factual. He never offers impressions of what they are thinking or feeling, which is what I’m referring to with that quote. In the film, we reflect a lot about what we show and what we don’t show, because we were very clear that we didn’t want to take the voices of Omarino and Aredomi. We needed to mark a distance between them, their voices, and our speculations in the film. Especially because speculations could potentially go in the direction of re-victimizing them. We didn’t want to position them as passive actors in their own history.

When we went into these Indigenous communities, we had to negotiate again about what was going to be told, and what was not. We understood that in these communities, people claim opacity as a way to protect themselves. Just as was the case with Omarino and Aredomi, there was a clear distance between ourselves and these Indigenous communities and we had to respect that. There were things that they decided not to tell us when we were there. We thought that these gaps of knowledge were good to have because they forced us to reconstruct the story, in opposition to the images in the archive.

D: The film raises ethical questions about using images from the colonial archive. The voiceover constantly interrogates whether it’s justifiable to use these images, which may be the only ones available of Indigenous people from this period, but which were produced under oppressive conditions.

TFS: We spent a lot of time during the editing process attempting to find a fair relationality to this colonial archive, a way we could use the archive against its original purpose. For instance, we decided not to use images which were promoting narratives of progress or development. We didn’t use images which were showcasing the industry, the ships, all this hardware, because we felt there was no way to “break” these images. This reduced what we could use, but actually from there, we found the film’s narrative style and its form. Then we started experimenting with repetition, running and re-running frames, to accentuate certain brief moments, to show you what we wanted you to see.

The archive images were silent, so we needed to think about how we could use sound to reveal what the images were not showing. We found that sound could help bring this uncontrollable world about, the idea of all these forces which exist in the Amazon—the force of nature, the magic of the territory, the animism that exists there. This also related to the opacity of the Indigenous cultures who live within the Amazon. Using sound helped us to create a connection. It was like opening a gate or crossing a threshold.

D: This idea of allowing a different reality into the material also seems to be reflected in the visual effects you use: flickering lights, repetition, images stained with blue or red tints. Can you talk a little about the creative process of editing this material, and mixing old and new footage?

TFS: From the beginning, I had this idea of transmission. I think photography allows transmission, something to do with the aura and with the light. There was also something in the uncertainty that we had, not knowing if we could tell this story. The use of visual effects was also about breaking the linearity of history. In my experience, the past and the present are never a straight line; sometimes it’s a spiral, sometimes it’s a snake. The past can also be a threshold, across which you may enter, but from which you also leave. This is why I began to use Super 8. I can hold this little camera close to my body, and that allows me to have direct contact with the experience of shooting which I can’t if I have to negotiate with a Director of Photography, to whom I have to explain how to do things. Instead, I had control, and I was not far from the actual experience.

In terms of structure, in the first part of the film we are mainly using images from the past, with occasional flickers from the present entering into the archive. In the second part, the opposite happens—flickers from the archive are interrupting the present. The editing process took two and a half years, working with three people, and it was mainly a long-distance process which was technically challenging. The editing process was in parallel to the shooting process. This worked well, because we would come with certain questions to the edit, and then when we could not answer them anymore we would have to go back out shooting. Then we would go back to the edit, where we would find more questions, which would send us back to the shoot. That’s how we worked.

D: As you describe there, halfway through the film there is a turning point where we start being more in the present day. For me, the bridge between past and present was this moment where you talk about your son’s ancestral relationship to the rubber trade, opening up a line of inquiry about ancestral responsibility. Why did you decide to include this more personal material?

TFS: The film is starting from this intuitive point, this suggestion that facts which appear not to be connected are actually related. In aiming to recover the stories of Omarino and Aredomi, I could not help but include the history of my son, because his ancestors were one of the richest families in this context. Not the richest, but certainly one of the families who most benefited from the rubber extraction. When I started researching in Iquitos, I found lots of archive about my son’s family on the paternal side, who were very well-connected politically and socially. In my speculation, I thought that it was completely possible that the family had known Roger Casement and that they were aware of the accusations that had been made against Casa Arana. I felt strongly that this point of contact was a reason why I had to tell this story.

I didn’t want to repair this history, because I don’t think it’s possible to repair anything, but I do think it is possible to transform. I thought the important thing was to acknowledge this tension, this position of responsibility towards the story of Omarino and Aredomi. How we answered those questions, in our intimate and personal space, was not relevant to the film so we kept that for ourselves.

Rachel Pronger is a writer, curator, and editor based in Berlin. She is also co-founder of the archive activist feminist collective Invisible Women. You can find her work at www.rachelpronger.com.