“There’s Affection But Also Skepticism”: Charlie Shackleton Takes Apart True Crime in ‘Zodiac Killer Project’

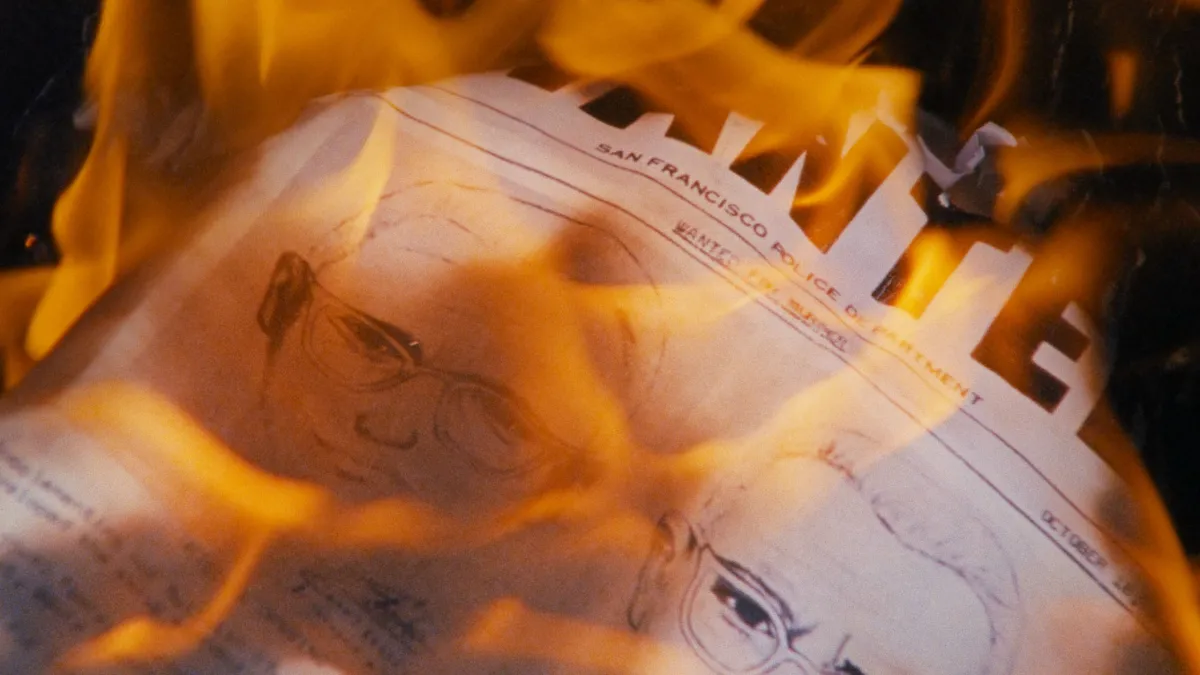

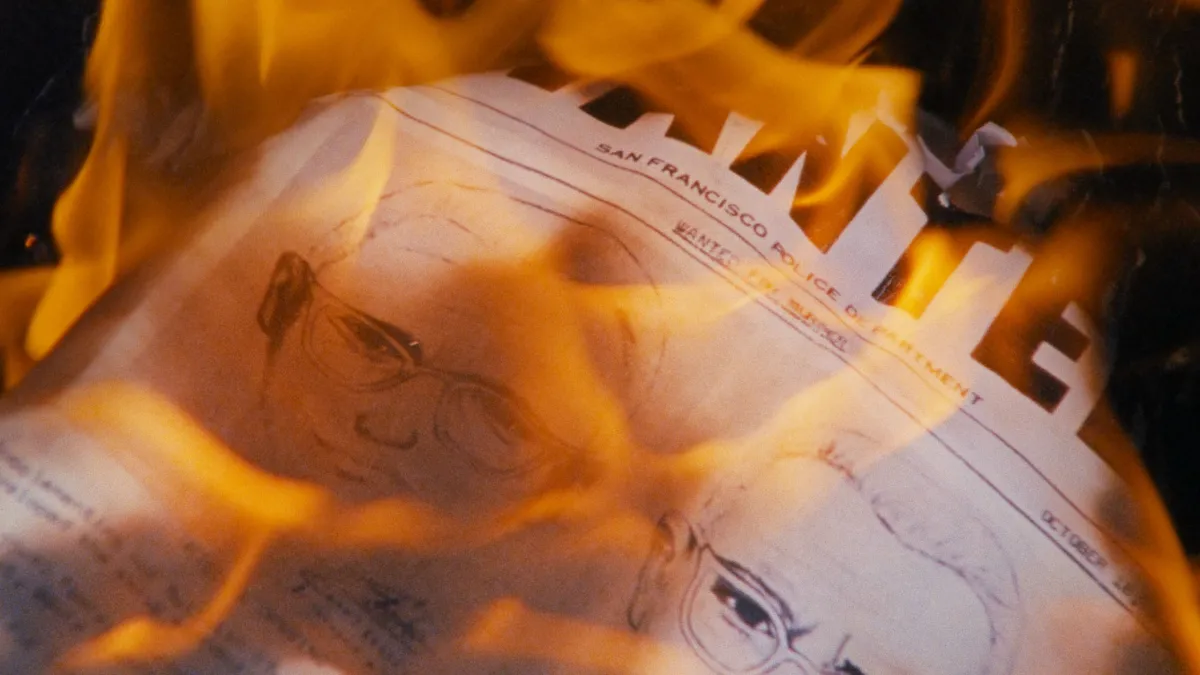

Courtesy of Sundance Institute

Prolific documentary essayist Charlie Shackleton’s latest film focuses on one of America’s most notorious criminals, the Zodiac Killer. Or rather, it’s a film about the documentary he would’ve made about the serial killer, had he been able to secure the rights to California Highway Patrol Officer Lyndon E. Lafferty’s 2012 true-crime book, The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up, which chronicles Lafferty ’s investigation into a man he indubitably suspected of being the Zodiac Killer. As he describes the project that didn’t materialize, Shackleton pokes fun at the tropes that have come to define modern true crime shows. This makes Zodiac Killer Project a film about the past, describing what could have been, while simultaneously dissecting what’s currently out there. It’s meta.

Shackleton’s previous documentaries include Beyond Clueless (2014), which analyzed the teen movie, and Fear Itself (2015), which parsed the horror genre from the POV of a fictional girl who’d developed a scary-movie obsession. Both display how Shackleton had deeply researched the material, but also maintained a level of distance from it. By contrast, Zodiac Killer Project feels deeply personal. “It’s slightly horrifying how much of my life, even in some small way, has been dedicated to this,” Shackleton told me over Zoom, explaining that he had toyed with the idea of making a Zodiac Killer documentary since 2019.

Most of the film is long shots of California landscapes contrasted with Shackleton’s voiceover description of what scenes he would have shot in those locations, and how he might have staged them.Vivid descriptions of a car gunning it to the highway are paired with a shot of flowers gently swaying in the breeze. At one point, Shackleton talks about the normality and banality of life in Vallejo only for a motorcyclist to appear in the shot, doing a wheelie down the street.

Zodiac Killer Project recently premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. For Documentary, Shackleton spoke about weighing art against artifice and the ethical considerations of true crime. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: Your previous documentaries, Beyond Clueless and Fear Itself, offer up appreciative analyses of the teen movie and the horror genre. By contrast, the narrative tone of Zodiac Killer Project is playfully derisive of true crime. At what point did you realize this was what the tone had to be and why?

CHARLIE SHACKLETON: I regret that I smoothed off the edges of my earlier films. I had a lot of complex, contradictory feelings about those subjects, but in trying to create a simpler package, I picked a lane and stuck with it. As a result, it was less my voice and more of a construction. Both of those films were narrated by actors, which solidified that it wasn’t really me. With this, I was trying to get closer to a truer expression of my own feelings about true crime. I did all the narration, which was improvised so I didn’t really massage it beyond deciding what to leave in. I wanted that feeling of contradictory emotion because that’s how I, and a lot of viewers, feel about the genre. There’s affection but also skepticism.

D: Was it also based on what you were watching? In Zodiac Killer Project, you talk about how all these true crime documentaries follow the same model. Was that something you consciously wanted to steer away from?

CS: My relationship with true crime was very love-hate. I was cognizant of the genre’s various ethical failings, but I still watched a lot of it for pleasure. It was during the making of Zodiac Killer Project, when I had to watch a lot of it not just for pleasure but for work, that the love slowly became outweighed by the hate. It’s hard to say whether I just became over-familiar with it and exhausted by it, or whether the genre became measurably worse. Streaming platforms reached a real saturation point, putting out a new series every week. What was already a formulaic genre became even more formulaic. It was quite mind-numbing but also useful — right down to the final stages of the edit, I’d just be watching something and then see another perfect example of a trope that I could drop into my film. The narration also became cathartic. I’d been at home watching all this stuff on my own for so long and then I got to let out my frustration with it.

D: The narration is also very conversational. It’s peppered with “you know”s. It doesn’t sound scripted. Did you have an outline?

CS: I tested out this idea of improvising my narration in a short film I did and found it really appealing because it was a technique that preserved the spontaneity that’s so easily lost while making a documentary. It’s really hard to capture those initial thoughts and feelings that led you to a subject. So I tried as much as possible to not script anything, even in my own head. If you get too firm an idea of what you’re going to say, you can find yourself reiterating what you’ve said before. So all I had were endless bullet points of potential subjects. Then, in the booth, I was just riffing on those as I was watching the footage. Obviously, a lot of the time, there was nothing happening, in which case it was my responsibility to find something interesting to say.

D: The film has this contrasting tonality. There are these sedate naturalistic landscapes and then these dramatic true crime trope-y shots, like that of a ticking clock. What discussions did you have with your cinematographer, Xenia Patricia?

CS: It was like we were making two diametrically opposite films. When we were in California for a week shooting those landscapes, we spoke about the meditative act of filming. We were surveying for atmospheres that the audience would absorb. Every shot was half a roll of 16mm film, so each was exactly five minutes.

By contrast, we filmed four or five seconds of each insert in the studio, which in hindsight was completely wasteful because none of them were onscreen for even one second. For one shot, we were filming one of our actors from over the shoulder as he was driving. It must’ve taken us two hours to set up. We had this beautiful vintage car brought to the studio, all this elaborate lighting and at one point, Xenia was like, “We’re getting a tiny bit of reflection in the corner of the windshield.” And I was like, “It’s not a big issue because this shot is going to be onscreen for just 10 frames.” And she looked at me with death in her eyes. All this effort for just an infinitesimally small moment.

I think the tones complement each other. The long landscapes feel even longer when you see the split-second inserts. And even the mundane inserts feel exciting when you’ve been watching an empty parking lot for five minutes.

D: Beyond Clueless and Fear Itself talk about what fictional tales can tell us about ourselves. Zodiac Killer Project is the opposite. You’re taking a genre based on real-life stories and exposing the artifice. You talk about all the ways you would’ve staged scenes to evoke specific reactions. You also talk about the cheats, like hiring an actor who would’ve sounded like Lyndon so people assume it’s the real Lyndon.

CS: That’s very interesting. It’s not something I’d thought about before but it’s true. A decade ago, I was a film critic. My engagement with cinema was primarily focused on fiction. I thought about how people consume movies and how our lives are interpreted and filtered through what we see onscreen. Since then, I’ve become primarily a documentary filmmaker so my thoughts are more in the realm of what happens when a process works the other way — when real life is filtered into art. It’s driven me to put all of these questions of artifice front and center in the film because within documentary filmmaking, that’s all we talk about. We’re all very frank about these necessary distortions and obfuscations. The best examples of documentary cinema are also frank with the audience. They encourage them to be skeptical of what they’re seeing. But just as often, the point is to lull the audience into a state where they’re not thinking about this at all.

This film doesn’t even get into the practical reality of these questions in the age of AI, when the artifice could be completely invisible to the average viewer. It could be an AI-generated voice or image. There have been a few high-profile examples, like that Anthony Bourdain documentary (Roadrunner). For every one instance people notice, there are 20 that fly under the radar. So it felt satisfying to put that into the text.

D: How do you weigh authenticity versus effect? Or the emotion that you’re trying to elicit? Like at one point, you admit you would’ve chosen a creepier house to stand in for Tucker’s real house just for impact.

CS: I’ve done those things in my own films in the past without drawing attention to them as I do here. You’re always weighing the value of the distortion against the ethical cost of the deception and deciding how far you can push something. There are plenty of justifiable minor deceptions, especially when the stakes aren’t as high as they often are in true crime. You couldn’t possibly make a nonfiction film that’s totally honest about everything because it would become an endless act of pedantry. The corrections would pile up quicker than the statements could be made. At best, I’ve seen people release footnotes for a film in an attempt to create a true record against an artistic statement.

D: You’re very aware of the kind of documentary audiences expect. One of the criticisms of the true crime genre is that it turns tragedy into entertainment—it’s predatory and exploitative. You say that if documentary filmmakers are convinced they’re working for the greater good, there’s no line they won’t cross. How did you navigate these ethical concerns?

CS: When I was in the recording studio performing all the narration, I tried to be as unconstrained as possible and, at that point, not worry about ethical considerations. The ethical choices came into play in the edit, when thinking about what to leave in. I don’t think you’ll get a clear answer as to how much it’s ethical to reproduce something in order to critique it, to gesture towards an ethical violation in order to say, “This is bad!” Even the most mainstream examples of true crime are constantly doing that. All these films and shows have sequences in which they go, “Is what we’re doing really ethical? And why do you, the viewer, want to see this?” It’s a genre that’s cannibalized its own critique. So I tried to set firm boundaries in the edit about how far we would go. Like there are no dead bodies in the film, there’s no discussion of any of the killer’s victims. This was a hard line.

Gayle Sequeira is a film critic and reporter whose work has appeared in The Guardian, BFI, Sight and Sound, Vulture, GQ, and more.