Few media arts centers last 50 years, let alone in Manhattan, where sky-high rents drive most out of business. But DCTV has survived for half a century. However, no celebration can be planned as long as Omicron is raging in the city. Co-founder Jon Alpert takes the long view, saying, “We want to survive, adapt, and be as relevant going forward as we have been for the last 50 years. That’s the best way to celebrate.”

The reasons behind DCTV’s success are many. But foremost among them are owning the property where they’re housed, the revenue stream from DCTV productions, and the dedication of its founders—the husband-and-wife team of Jon Alpert and Keiko Tsuno, who remain at the helm.

In the Beginning

The story begins in 1970. As community activists, the couple was trying to oust a corrupt school board in Chinatown. “The basic building block of American democracy is the school board; this is the level at which people begin to engage in politics,” Alpert says. His father had been a school board president. “So from an early age, this was the cathedral of American democracy as far as I was brought up.”

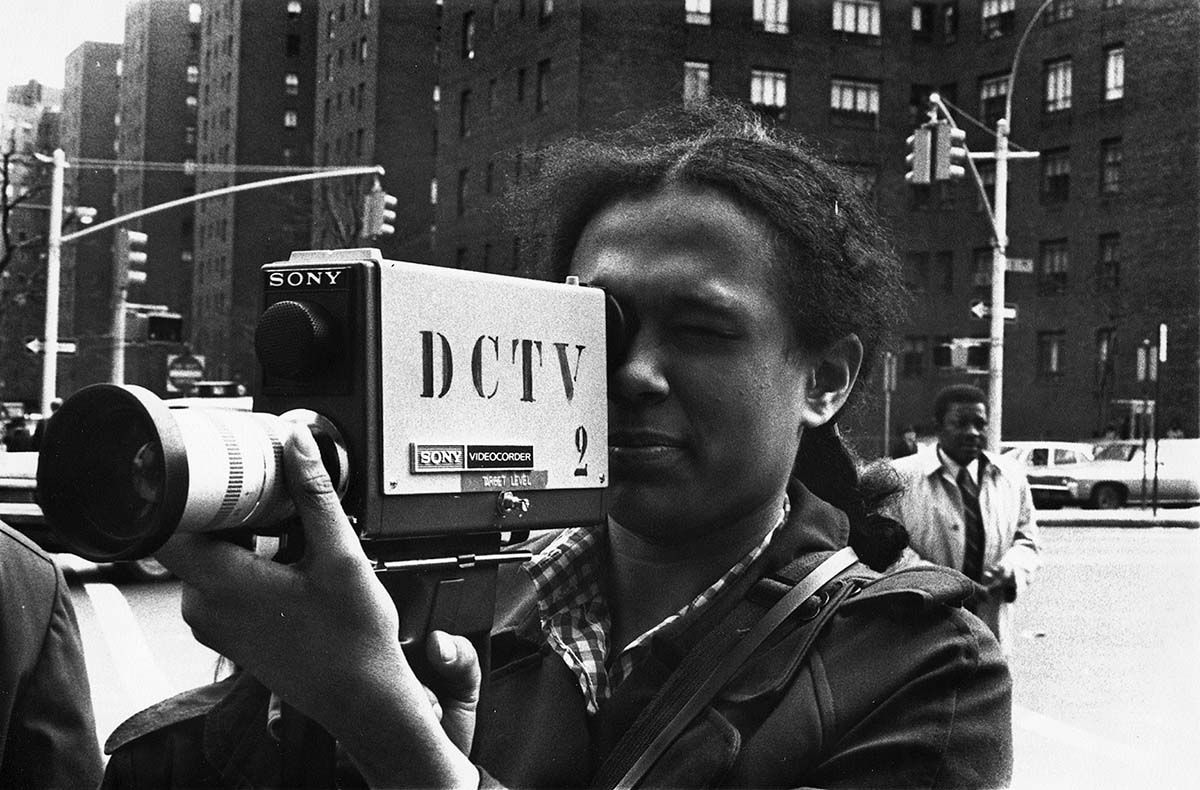

Alpert and Tsuno made no progress until they brought an early black-and-white Sony portapak to a board meeting. The meetings weren’t democratic, parents weren’t allowed to speak, votes were railroaded through, and police stood in the wings ready to haul anybody out who protested. But the resulting videotape brought the parents’ complaints to life and that video made all the difference; the school board was ultimately thrown out.

“That was the Kool-Aid for us,” says Alpert. “We saw the power of media to accomplish things we’d been unsuccessful in doing in all our community organizing. From there, we went on to use video to try to improve health conditions, housing conditions, working conditions.”

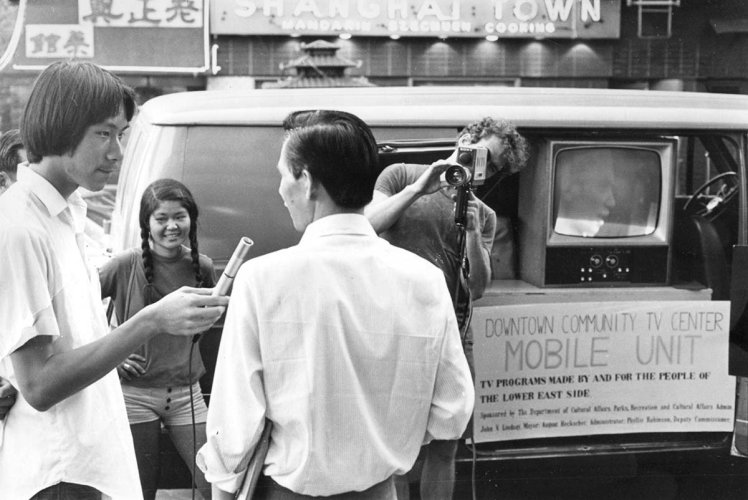

The couple bought an old mail truck and set up in Chinatown parks and street corners, showing videos in various languages to help the community learn English, ride the subway, go to the dentist, and so on.

As Tsuno notes, “Neither of us had studied film. Of course, there were no video courses back then. We had no idea how to make documentaries. All we knew was that documentaries should be one hour or less. We learned from the street.” Alpert adds, “The sidewalk was our teacher, especially the empty sidewalk.” Tsuno continues, “We’d come back home and start cutting shorter and shorter and shorter. Then we watched the people’s reactions. When they laughed, it worked; when they walked away, [we thought], Oh boy, this part is too long,”

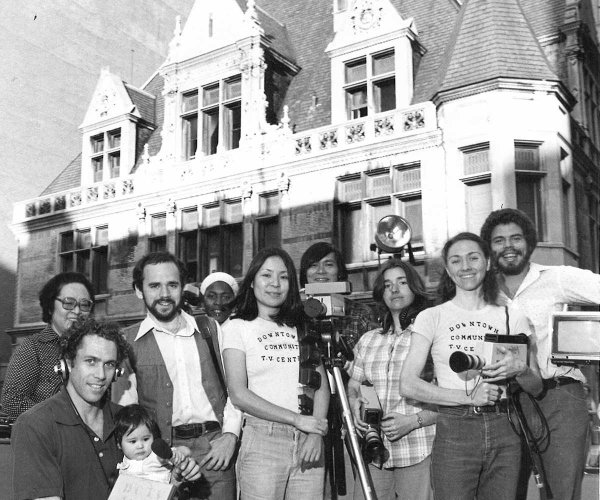

Alpert and Tsuno started offering free courses out of Tsuno’s loft on Canal Street. Eventually, the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs got wind of what they were doing and paid a visit in 1972. “They saw community video for the first time,” Tsuno recalls. “The person was very impressed. He said, ‘We’d like to give you a grant, but we cannot give money to individuals. You have to establish a nonprofit organization.’ ” So that night, she and Alpert did the paperwork to create DCTV.

The Secret to Success

Alpert and Tsuno affirm that owning the firehouse where DCTV is based is a big reason the organization has survived. Even though the couple’s loft was nearby, neither had paid much attention to the abandoned 1895 firehouse on Lafayette Street, despite its unique Loire-chateau appearance, until they were dog-sitting for a friend. During a walk, Alpert noticed a small sign in the window. He called the number, and soon after they were renting the second floor for $500 a month, moving operations there in 1978. “That really allowed us to expand. The classes increased ten-fold,” Alpert says. Eventually they were able to buy the entire landmarked building, which is vast enough to allow the expansion of services to this day, including a new state-of-the-art cinema. The other key to survival is this: “DCTV is different [from other media arts centers] in that a majority of its finances are self-generated through our productions,” Alpert states. Revenue has come from PBS, NBC, HBO, and other outlets for Alpert and his teams’ documentaries produced under the banner of DCTV.

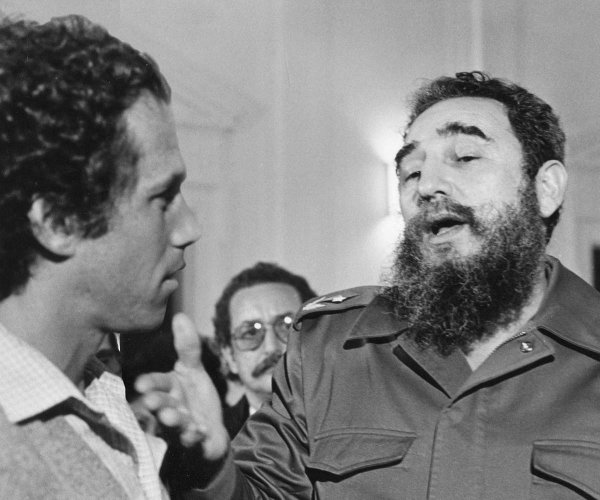

The first breakthrough was Cuba: The People in 1974, the first independently produced color documentary, according to Alpert. “That was our toe in the door to public broadcasting,” he says, noting that PBS and other broadcasters kept independents off the air by requiring color video, which no indies shot at the time, unless it was film. Alpert and Tsuno knew nothing about film and couldn’t afford to learn.

But Tsuno’s connections in Japan gave them access to the latest video gear. “Keiko’s brother would literally go to the factory, and as the first color portapak was coming off JVC’s assembly line, we’d get serial number one of everything,” Alpert says. “We were the guinea pigs, the beta testers, the war-zone testers.

Cuba: The People led to a run of five documentaries on PBS. But relations soured after Your Money or Your Life, a film on the disparities of health care between rich and poor in two New York City hospitals. Alpert found himself blacklisted—a “negative milestone,” he says.

Then a window opened at NBC. Being familiar with Vietnam from their 1977 documentary Vietnam: Picking Up the Pieces, Alpert and Tsuno suspected that war would break out between Vietnam and China over their border. They applied for a visa, which took six months at the time. “The day the war started was the day our visas came in,” Alpert recalls. After PBS said no, the filmmakers caught a break from George Page, vice president of WNET and a former NBC correspondent. He made a phone call to NBC, mentioning the visa, which no one else had. “Half-hour later,” Alpert recalls, “we had a handshake from NBC, who thought, ‘What have we got to lose?’”

Despite being neophyte war correspondents and facing resistance from their Vietnamese handlers, the couple managed to get to the front line, then into Cambodia, where they were the first to document the killing fields on video. “NBC couldn’t ignore us. We basically hit six home runs at two times at bat,” Alpert notes. They learned how to cover wars. “We went from war zone to war zone to war zone.” For their war reportage, Alpert and his co-producers earned multiple Emmys, a Peabody, a duPont-Columbia Award, and more.

The long, fruitful relationship with HBO began with 1989’s One Year in a Life of Crime, a portrait of three drug-addicted criminals in Newark. Alpert returned in 1998, then again in 2020, creating the epic Life of Crime 1984–2020, one of DCTV’s many collaborations with HBO.

Meanwhile, youth and student productions at DCTV have been racking up awards as well. In addition to four local Emmys, these productions have won prizes at Sundance, Tribeca Film Festival and Tokyo Video Festival. Their shorts have been packaged as series, like 2014’s Our Cameras, Our Stories on WNET and 2020’s COVID Diaries on HBO. “I’d say that’s the first time any youth program in the country got nationwide distribution on a major network,” Alpert says about the latter.

But Alpert is proudest of their on-going success story—the fact that the vast majority of high school students who enrolled in their Youth Media programs have continued on to college. Since a good percentage of them are lower income from Title 1 public schools, that’s “a demographic you would not normally have a statistic like this in,” Alpert observes. In addition to free Youth Media classes, DCTV offers college counseling and portfolio reviews in preparation for the college admissions process. They also provide students with opportunities for professional development, including internships and job placement with DCTV productions for shows on HBO and elsewhere, and as part of PA training programs throughout the city.

DCTV also offers MFA-level classes for adult filmmakers that are designed to make professional filmmaking education affordable and accessible. Some recent works that have gone through their free Docu Work-in-Progress Lab include Nathan Fitch’s Drawing Life (online premiere on The New Yorker), Anthony Banua-Simon’s Cane Fire (MoMA’s Doc Fortnight), Lisa D’Apolito’s Love, Gilda (Emmy nominated), and G. Anthony Svatek’s .TV (New York Film Festival).

What Lies Ahead

If it hadn’t been for COVID, much of their 50th anniversary celebration would have been planned around events in their brand new theater, the DCTV Firehouse Cinema. Except for some private test screenings, the 74-seat theater hasn’t opened yet. When it does, it will be a much-needed downtown arthouse for documentary film, showing both DCTV productions and outside programming (including DocuClub’s work-in-progress screenings in conjunction with IDA). Interactive technology is built in, so events could go national. Publicists and filmmakers can host four-wall screenings; the theater could also be used for filmmaker services like color correction and audio finishing. The idea is that the theater will pay for itself. There’s room for a second screen too, if they sacrifice a garage, which could potentially result in a profit.

But that’s a dream for the future. This one took 20 years to bear fruit. Initial funding for the theater came from a 9/11 stimulus package, but the city’s red tape bogged things down for years.

The upcoming National Youth Media Center is another project that’s long in the works. When the Bloomberg Administration sold The Clock Tower Building two blocks south of the firehouse, part of the deal was that the developer had to create a community resource. The Department of Cultural Affairs asked DCTV to run a media center. “It’s astonishing this is going over three administrations,” Alpert says. “But eventually we’ll fix that place up and make a really nice media center.” They have 16,000 square feet to do so, and plan to move all of their youth programs there.

But DCTV faces a new threat: a 300-foot-tall “jailscraper,” approved in 2019 as part of a plan to close the notorious jail on Rikers Island and replace it with four high-rise correctional facilities in the boroughs. The plan entails tearing down the Chinatown jail, last expanded in 1982, and replacing it with this tower. “This is an existential threat to DCTV,” Alpert insists. “The last time the firehouse sank, it was exactly because of this local construction, because they draw the water table down in order to be able to construct. We have wood pilings. They’re fine when they’re underwater, but as soon as the water table goes down, they rot out. When they do this project, the building will fall down, guaranteed.”

So they’re making a film about it. “It’s one full circle in 50 years,” Alpert says. “We were powerless in those days to accomplish the things we needed to do to make our neighborhood better—until we began making films.”

Looking back, Alpert emphasizes, “This was not 50 years of smooth sailing for DCTV. If it was easy, there’d be a DCTV on every corner. But we really believe in what we’ve done and can do. If the building collapses, they’ll find my body and Keiko’s in here, because we’ve basically given our lives to the organization.”

Patricia Thomson is a longtime film journalist and a contributing writer for American Cinematographer.