“Sometimes There’s Boiling Energy”: Collaborative Improvisations in Antoine Bourges’ Docufiction

By Winnie Wang

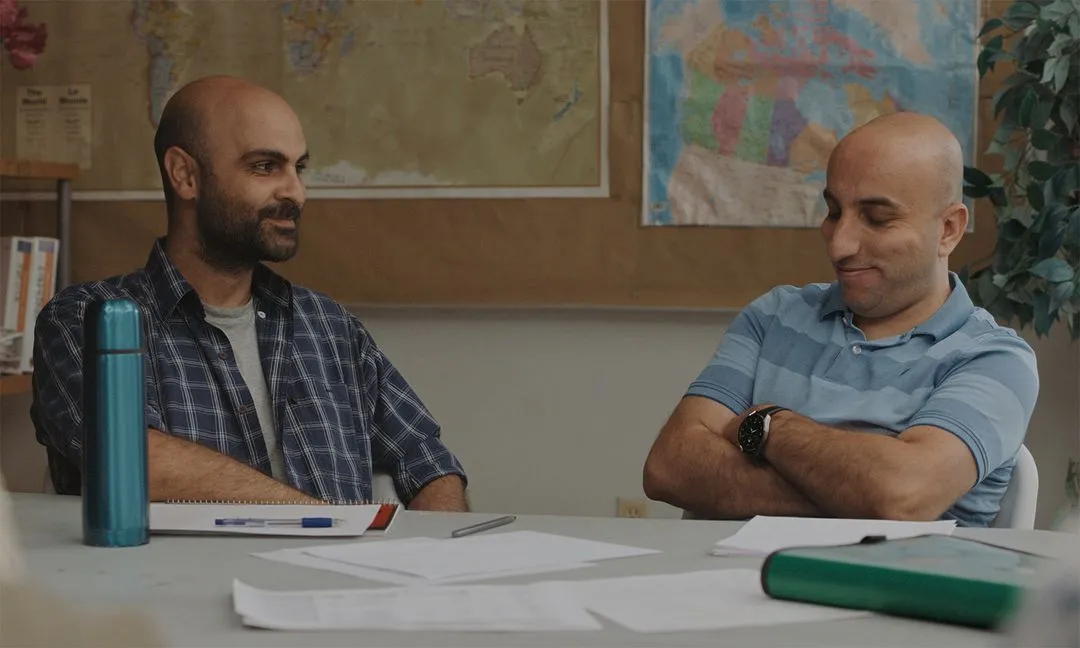

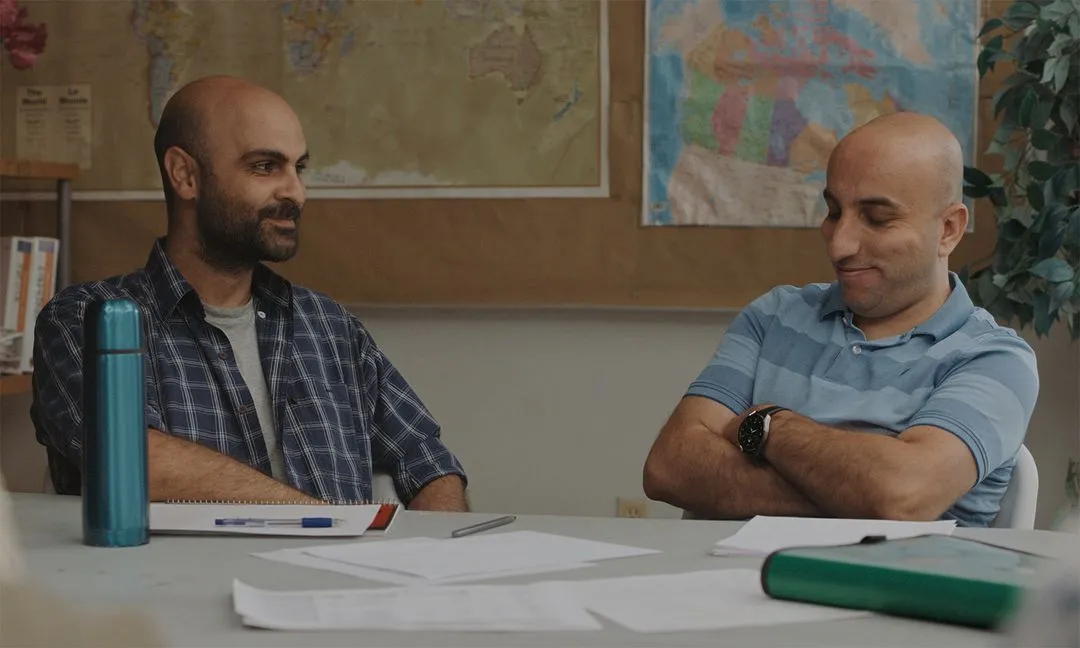

Film still from Concrete Valley. Courtesy of Metrograph

Softening the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction, the films of French-Canadian director Antoine Bourges are marked by their hybrid nature and his collaborative approach with participants. Whether in Vancouver’s Downtown East Side or Toronto’s Thorncliffe Park, Bourges captures everyday details of the surroundings he finds himself immersed in, introducing individuals and communities in the margins to the big screen with care and curiosity. Growing up in the neighborhood adjacent to the one depicted in Bourges’ latest, Concrete Valley (2022), I was amazed by his portrayal of a vibrant, immigrant community that had been overlooked by even Toronto locals—children playing in green spaces at the foot of high rises, awkward conversations during English class for newcomers, apartment residents delivering meals to one another. There’s a real sense that Bourges, who has also lived in Paris, Montreal, and Vancouver, is able to tune into a unique wavelength regardless of where he calls home, locating formal and informal networks of power.

Between February 23–25, New York’s Metrograph will present “Minding the Gaps: Films by Antoine Bourges,” a retrospective of Concrete Valley, Fail to Appear (2017), and the Downtown East Side trilogy of shorts, consisting of William in White Shirt (2015), East Hastings Pharmacy (2012) and Woman Waiting (2010). In advance of the series, Documentary spoke with Bourges about crossing boundaries of fiction and documentary, crafting characters with participants, and how individuals negotiate with institutions. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: Your works are sometimes described as “docufiction” and often screen at documentary film festivals such as RIDM, DOXA, Cinéma du Réel and Camden. How would you describe the relationship between your filmmaking practice and nonfiction? Is hybridity something you’re consciously trying to negotiate?

ANTOINE BOURGES: I try to get what I like from both. I enjoy simple things about fiction like continuity, like seeing someone walk in a door and seeing them appear on the other side, knowing that something like that could’ve been made over three days and we believe it’s happening in two seconds. But I also like elements that concern documentary—people appearing on screen who are not fully scripted or are scripted but are not trained to be actors, going into situations where I’m discovering as I’m making, allowing the participants to teach me and direct me as we’re working on the film together.

D: Have you noticed any differences between audiences at festivals that are dedicated to documentaries compared to those that aren’t? I’m curious to know whether an association with documentary affects how you present your films, and how they’re received.

AB: The type of questions and the way that people engage with the work are different. If you watch any of my films, you can engage with whatever narrative they’re telling, but you’re also free to engage with the mode of making. People who watch them at documentary festivals are more inclined to experience the films on both layers. They’re following the story, even in my films with the least narrative, but they have an interest in trying to understand how it’s made and seeing the making of as they’re watching.

D: The ending of East Hastings Pharmacy states that the film was made through “collaborative improvisations and reenactments with residents” of Vancouver’s Downtown East Side, and Frank Studdhorse, who appears in the film, is the central character in William in White Shirt (2015). You’ve also mentioned that some of the performers from Concrete Valley are from Thorncliffe Park. Can you talk about these collaborations and how you approach working with actors and nonactors?

AB: It starts with curiosity in something that I don’t know. With East Hastings Pharmacy, I lived in that neighborhood and would walk past these methadone pharmacies all the time. I didn’t see them consciously for years before I paid attention and spent time in them. I wasn’t necessarily actively looking for participants at that point, but when you start meeting people, they’re there every day, and if you go there often enough, you start to become more acquainted. It was similar to Concrete Valley. I would go to Thorncliffe Park, ended up spending a fair amount of time in the English language classes for new immigrants, and would meet people in those classes. The goal was just to start shaping what this film was going to be about, but when it came to trying to find performers, I already had all these people that I had spoken to. It’s kind of a seamless process that’s been the same for almost everything I’ve made, where the research ends up being kind of the casting.

D: I’m struck by the name of the retrospective, “Minding the Gap.” In other words, to draw attention to something that would otherwise be overlooked. It’s an apt way of describing the communities you’ve depicted. What draws you to these places and people when you arrive in a city?

AB: It’s not so much that I’m actively seeking them. For some reason, I’m interested in places that are in the margins, people who are in the margins, but it’s never a conscious thing—I think I’m interested in how things happen in the everyday. The representation in the media of the Downtown East Side is one thing, but when you spend three hours sitting in a pharmacy, your experience and appreciation and your bodily experience of what it is to be there is different from how it is perceived. The pharmacy is an incredible vantage point for the whole city of Vancouver. You get a glimpse of their lives between the moment they walk in and they walk out. You hear what they’ve been doing, how things are going in relationships, things they’re doing with their friends. It’s a place that’s extremely rich.

D: On the topic of your participants, is representation something that you’re thinking about when you’re creating characters? Some are fictional versions of people in real life whereas others are composites of various people and conversations.

AB: When you cast nonactors, you cast them for whatever presence you sense in real life. That’s what you want to bring to the film, but I want them to know what it will mean to have their presence in front of people on a large screen. Some people are like, “Yes, that’s precisely what I want. I want this experience to be seen,” and others are like, “Oh, I’m not so comfortable,” and then we just don’t work together. I always want to give them agency, and so we work on creating the distance between them and the character as much as they feel the need to. I ask them if they would like to choose a character name. Whenever I think of something that I’ve seen them do during research, I run it by them: “Hey, I know you happen to bake cakes for people in your building. It’s an interesting element that I would like to incorporate in the film. Are you okay with your character doing that?” But it’s also exciting when they incorporate traits that are not close to them.

D: Your latest work Concrete Valley has been compared to Robert Bresson, Angela Schanelec, and Kelly Reichardt. Another filmmaker that comes to mind is Frederick Wiseman, who has dedicated much of his career to examining institutions. Who are some of your influences as a filmmaker?

AB: I think [Wiseman] was a huge influence, probably way more than Bresson actually. You discover something about people when they are within an institutional setting. They have to have a certain behavior and can’t completely lash out. There’s a kind of theatricality. Sometimes there’s boiling energy, sometimes it’s a little bit more tame. You discover people who are fighting for things that are life and death, but they’re controlled. There’s this mystery and energy pushing against a barrier in his films. East Hastings Pharmacy is just a series of people coming to a counter and asking for something, and the person behind the counter has to perform in a certain way to negotiate certain tricky situations. This layer of institution adds something to the dynamic between people that’s fascinating.

D: What are you working on next?

AB: My mother tongue is French and I’m from France originally. I’ve always been curious, especially after working on Concrete Valley where people speak Arabic, which I don’t speak, about the slight disconnection that I’ve always felt with all of my films that are in English.

Winnie Wang is a writer, film programmer, and arts administrator based in Toronto.