Editor’s Note: First given in 1985, the IDA Career Achievement Award is presented annually to an individual film or video maker who, through a body of work, has made a major and lasting contribution to the documentary form. The recipient is selected by the Board of Directors of IDA, which publishes Documentary. Previous honorees include Julia Reichert, William Greaves, Les Blank, Sheila Nevins, and Errol Morris. This interview was conducted with the 2025 recipient, Julie Goldman, who has fearlessly shepherded critically acclaimed documentary features for over a decade under the Motto Pictures banner.

Julie Goldman’s first job in film was selling documentaries to librarians at First Run/Icarus Films. After meeting in film school, she and Chris Clements dove into filmmaking by maxing out their credit cards and calling in favors with friends to make Free Floaters (dir. Clements, 1997). From there, she worked at Winstar/Wellspring and Cactus Three in the early 2000s, truly cutting her teeth in earnest in docs and co-productions. By 2010, she reached a pivotal moment. Simply put, she wanted to “capital P” produce. Alongside Clements, her partner in life and film, she launched Motto Pictures. The company’s ethos would be based in creative producing and executive producing, cultivating each project’s path individually and working in deep collaboration with filmmakers. The caliber of credits—and the number of returning directors, producers, and financiers—speaks to its success.

The resulting filmography is a crash course in modern American documentary filmmaking. Goldman produced films that were nominated for Oscars (Life, Animated, 2016; Abacus: Small Enough to Jail, 2017; and more), won Emmys (Best of Enemies: Buckley vs. Vidal, 2015; The Apollo, 2019) and Peabodys (A Thousand Cuts, 2020; In the Same Breath, 2021), and shifted conversations on a global scale (One Child Nation, 2016). She has accelerated the careers of filmmakers such as Roger Ross Williams (also a previous Career Achievement Award honoree), Nanfu Wang, Alison Klayman, and Kristi Jacobson. Motto Pictures is a steadfast beacon in the increasingly unstable waters that is documentary production in the United States. But with all the credits and awards, what’s most remarkable in speaking with Goldman is how often she mentions the people she’s worked with. She’s not name-dropping but rather naming her community.

In the 2010s, Goldman helped guide the company through the “Golden Age of Documentary”—a term she rejects—and its inevitable bust. While Motto explored new platforms like Facebook with the series Humans of New York and worked with streamers, the company remained rooted in building something sustainable. (Goldman and Clements never stopped working in an international co-production model, she points out.) So, while others floundered, Motto continued on, expanding into fiction (“Stories are stories,” she says). This fall, two of Motto’s projects came out within days of each other: Selena y Los Dinos and season two of A Man on the Inside, based on Maite Alberdi’s The Mole Agent (2020).

In our conversation, Goldman often laughs—at herself, the absurdity and immense challenges of this moment, and the often-delusional pursuit of bringing stories to the screen. It’s this quality that belies the key ingredient to what she calls the “alchemy” of producing. Though she’d never say it, it’s clear that it’s Goldman herself. This interview has been edited.

DOCUMENTARY: Congratulations on your IDA Career Achievement Award. How does it feel?

JULIE GOLDMAN: It feels great. I feel one, stunned, two, old, and three, delighted.

D: Your body of work spans critical moments in contemporary documentary. What do you see when you look back on it?

JG: I don’t tend to look back because we have so much going on all the time. When I do, I think about the people that we’ve worked with over all these years. You can’t divorce the years that you spent on each project and all of the people that you collaborate with—the good, the great, the bad—all of the journeys that have been. Each one is so profound.

D: Not to go all the way back, but did storytelling play a role in your childhood in any shape or form?

JG: Absolutely. My mother was an activist with a great sense of humour. You don’t usually find those two things together. She really passed on her love of film, and we would go all the time to see movies. She had her own interesting journey that involved working as an apprentice for [John and Faith] Hubley and almost being arrested because she was filming something out of a window, [which] turned out to be a munitions plant. That shifted her path, but she instilled that love of film in me.

Also, when I was a child, [film critic and professor] Phillip Lopate taught a college film course in my elementary school. Battleship Potemkin. Citizen Kane. The Bicycle Thief. He did this as a kind of experiment to watch our reactions, because we were in fourth grade. The school also brought in a group called Teachers and Writers Collaborative that we made films with. We wrote scripts and filmed on location around NYC. That combination completely changed me.

D: Did this intersection of activism and art draw you to documentary?

JG: I grew up going to protests. There were a very big worldview and views about justice and injustice in our house that absolutely influenced how I saw films. I remember seeing Harlan County USA (dir. Barbara Kopple, 1976) when I was really young with my mother. It didn’t seem that different to watch a documentary versus a fiction film.

Julie Goldman (L) in conversation with Roger Ross Williams (R) at Getting Real ’16. Image credit: Susan Yin

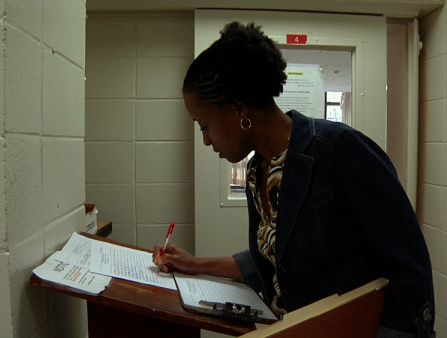

Gideon’s Army (dir. Dawn Porter). Courtesy of Trilogy Films

Abacus: Small Enough to Jail (dir. Steve James). Courtesy of PBS

D: What aspect of producing originally drew you to it?

JG: I’m a Virgo. I love to be organized and have everything set and ready to go. I like the creative aspects of producing. Whether it’s working on development, research, all of the editorial stages. Budgeting, scheduling, and problem solving are also really creative. They can truly be a source of pleasure. Of course, when you don’t have enough money, it’s less of a pleasure. [Laughs.] I will say, I don’t love being on location. But Chris is totally absorbed in and on top of the creative, so I can go across everything. I like that bird’s-eye view and knowing what’s going on. That’s where I find my satisfaction.

D: How do you approach conflict, which inevitably happens?

JG: I’m very direct, to a fault. I don’t tend to shy away if there’s a problem. We’re born and bred New York City people, so we can’t help but be loud and direct, I suppose. There’s more conflict with making sure that our directors are being treated well by third parties than between us and the directors. You just have to try to focus on the creative and on the practical, and work through it together. If there are people that you can do that with—because it is inevitable that there’s going to be times like that—then you know you want to work together again, as we do with Roger Ross Williams, Maite Alberdi, Kathlyn Horan, and more. If you can’t do it well and it’s not as seamless, you may not work together again, but maybe you’ll still be pals.

D: Can you talk about the so-called Golden Age of the 2010s? You made incredible films in this period and were Oscar-nominated twice.

JG: It wasn’t a Golden Age. It was a bubble. If you’ve done something for long enough, you know when it’s a bubble. You feel it. You say, “Okay, let’s ride this out. Let’s see where we can get to. Let’s see what opportunities we can unlock.” But not at the expense of looking forward and understanding this is likely to shift.

[At that time] there were a few people who had money thrown at them in a massive, out-of-balance way. Even in that bubble, something like Abacus [dir. Steve James, 2017] was still piecemeal raising money. And we still were doing international co-productions. We didn’t start working with global streamers for every single project.

What made it even more of a bubble was that everybody was getting in on it. Every actor had a company with a documentary division, and giant companies that didn’t really care about documentaries were also creating documentary divisions. We had a lot of conversations with companies that were interested in buying us, and I’m so glad we didn’t go through with it. We had a pretty clear view. We didn’t go crazy and expand, hire 20 new people, or rent other offices. That’s how we are able to ride out that moment.

We definitely had a lot of good fortune, and many projects were brought to us fully funded. That was the excitement: you could focus on making the films without worrying about raising money all the time. That’s a dream. And that dream is over. Now it’s back to scrappy.

The metric of success is being able to make a living doing what you love. Being able to make films that show all different parts of the human adventure—misadventure—and make a difference in people’s lives.

Julie Goldman

D: How do you approach building a slate and weighing capacity, capitalism, creativity, and care?

JG: We really spend a lot of time thinking about balancing subjects, ideas, personalities, and also projects that we have to raise money for and ones that are fully funded. We’re really cautious about taking on too many projects where we’re raising money, because we tend to go to a lot of the same sources, and I don’t believe in cannibalizing our films. We’re also very cautious about who we’re going to be working with. We don’t do ten projects with the same place. We don’t do overall deals. We don’t do anything that locks us in.

That gives us a fresh start for each project. We can ask, What are the hopes and dreams for this project from day one, and how do we evolve that as we go? What’s the best way to make each one? What’s the best way to get each one into the world? It’s a weird alchemy of trying to figure out all these factors and how they can fit together best.

At Motto, we really have a great group of people. When projects come in the door, we tend to assess them as a group. It’s not the situation where Chris or I say, “We’re doing this next.” We make decisions with input from everyone. It’s also about weighing who at Motto will be excited and vibe with a project. Many people who have worked here as interns or assistants have come up as APs, co-producers, and full producers. Carolyn Hepburn, who produced with me and Chris for years before going to ESPN. And now, Daniel Torres, Samantha Bloom, and Kendall Marianacci. It’s wonderful to have that kind of mentorship.

D: I’m so glad you brought up mentorship, because I don’t think we honestly have a lot of it in the producing world.

JG: No, we don’t. I really didn’t have a lot of it. Working with HBO early on was really helpful. I learned a lot working with Nancy Abraham and Sheila Nevins. I’m really, really happy to be a mentor where I can, because I could have learned a lot more quickly if I had that. People will say, “I really feel like you mentored me,” and I find it hard to believe. [Laughs.] At Motto, we tend to be really open and try to be generous with advice and feedback. Personally, I have people like Caroline Kaplan, who I will always go to. And Chris and I discuss everything.

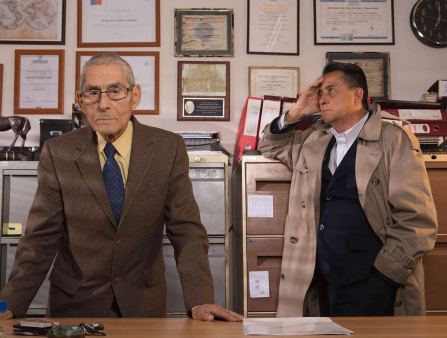

The Mole Agent (dir. Maite Alberdi). Courtesy of Gravitas Ventures

Southwest of Salem (dir. Deborah S. Esquenazi). Courtesy of Southwest of Salem

One Child Nation filmmakers (L to R) Jialing Zhang, Nanfu Wang, Chris Clements, Julie Goldman, and Carolyn Hepburn at the 2019 IDA Awards. Image credit: Jesse Grant

D: With your slate being so diverse and films having so many different paths, what’s your metric of success?

JG: The metric of success is being able to make a living doing what you love. Being able to make films that show all different parts of the human adventure—misadventure—and make a difference in people’s lives. I’m so grateful for it. I think of Southwest of Salem by Deborah S. Esquenazi, where four women were railroaded and imprisoned for years and years. That film ended up becoming part of their exoneration. Or A Thousand Cuts [an IDA Enterprise grantee] from Ramona Diaz, about Maria Ressa. Frontline allowed it to be on YouTube in the Philippines before it premiered on PBS, and, at that moment, it really made a difference in public opinion during Ressa’s trial. These moments, you just don’t imagine you’re going to have a life like this. Why stop? First of all, we don’t make enough money to be able to stop. [Laughs.] And secondly, it’s a complicated combination of stress and struggle and joy and absolute delight in what we do.

D: It feels very precarious right now between the COVID slump at theaters and festivals, the defunding of ITVS, and this media market contraction. Do you have a forecast of optimism for documentary filmmakers and producers?

JG: There are so many things that are at play right now. The biggest one is that it’s been nine months since Trump came in, and the rights that have been rolled back are astonishing. A lot of the companies that we’ve been getting our financing from are in flux because of their response to this administration. And PBS, which we have always been very involved with—it’s just disastrous. It’s never been everything at once like this.

We just have to find other creative ways to get our films made. Some people will leave and have other careers, and some people will keep going. We’ll have to use our ingenuity and our community, be present for each other, and help each other make the films. And we will figure it out. It’s as simple and as equally complicated as that.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Winter 2026 issue.