'The Art of the Real' Takes the Long View on Nonfiction

Since the beginning of film, the documentary form has often fudged the line between real and imagined, resulting in an intriguing canon of doc/fiction hybrids. The Art of the Real series, which recently concluded its inaugural run at Lincoln Center in New York City, is devoted to this kind of film, showcasing both well-known historical examples and lesser-known work of many contemporary filmmakers, both domestic and international.

"We wanted to expand our sense of what a nonfiction film could be," says Dennis Lim, director of programming at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, via email. "In part, we were responding to the increasing dominance of a certain type of documentary (i.e. informational, journalistic, and much more interested in content than form)."

Grounding the series with Jaguar (1954/67), the pioneering film by Jean Rouch, and several classics of the genre including Derek Jarman's Blue (1993), Robert Gardner's Forest of Bliss (1986) and Paulo Rochas' Change of Life (1966), Lim and programmer Rachel Rakes also offered an impressive array of diverse contemporary films.

In The Second Game, from Romanian director Corneliu Porumboiu, an actual TV tape, stripped of commentary, of an entire 1988 soccer game played in heavy snow in Bucharest is turned into a meditation on history, space and change. The match, pitting teams backed by the Romanian secret police (Steaua) and the national army (Dinamo), was refereed by Porumboiu's father the year before the collapse of dictator Nikolai Ceausescu's regime. The droll soundtrack consists of the filmmaker and his father talking throughout the game about the past and the present. At one point the director remarks that the game is like one of his films: "It's long, and nothing happens." Using a historic artifact, Porumboiu recontextualizes it to reflect on both national and personal history.

Another self-referential foray into national and personal history is Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop's A Thousand Suns. Working with Magaye Niang, a non-professional actor who starred in Touki Bouki (1973), by Dopi's uncle, Djibril Diop Mambéty, Mati Diop creates a new story, using the older film narrative intertwined with Niang's life story. At the end of the 1973 film, as Niang's character and his lover are supposed to sail away from Senegal to Paris, he suddenly cannot leave, and she leaves without him. Forty years later Mati tracks down that actress in Alaska, and convinces Niang to call her. We see this phone call, and Niang is transported by the magic of cinema to a huge snowy field, still in his skimpy old clothes, where he struggles through deep snow. Coming upon a kind of hot springs, he has a vision of his young lover walking in the distance, disappearing into the mist. Diop's contemporary account subtly references the complex colonial past of Africa, refracting that history through a universal tale of love and loss. With its elegant cinematography, A Thousand Suns is both enticing and elegiac.

Also included in The Art of the Real are more familiar "observational" documentaries. Foreign Parts (2010), from Véréna Paravel and J.P. Sniadecki, profiles a car junkyard at Willetts Point in the Queens borough of New York City prior to a large redevelopment there. Through several seasons, with long takes, we come to know the characters living and working there. We share their birthdays, their Friday night get-togethers, and the much anticipated return of one young man from prison. Equal time is spent on the landscape of this urban graveyard: rows of cars being crushed, and racks and racks of spare parts. Foreign Parts screened as part of a tribute to the Sensory Ethnography Lab, an experimental laboratory at Harvard University that promotes innovative combinations of aesthetics and ethnography.

Another product of the Sensory Ethography Lab, Sweetgrass (Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor; 2009), is an almost dreamlike portrayal of sheep-herding in the mountain valleys of Montana. Through long, slow sequences creating a palpable sense of natural time, and with a focus on the spectacular landscape, the film follows cowboys and their herd through the seasons, culminating in the inevitable drive to market. Like Foreign Parts, the environment and its characters (sheep included) are given equal weight and equal time, imparting a kind of epic quality to otherwise everyday events.

Another kind of film investigating a history is Tai Pin Pin's quite fascinating To Singapore, with Love. The filmmaker tracked down political exiles from the 1960s and '70s who are now living in London, Thailand and India and interviews them at length about their experience. While they still cannot return without facing possible imprisonment, each exile keeps up with news and developments coming out of Singapore. Through archival segments we learn the activist history of each exile, and why they chose to leave. We cannot help but be moved as they describe their hopes and dreams from the past, and how they have coped as immigrants in their adopted countries. Most have done well—teaching and writing, starting businesses and gaining citizenship. Most striking is their continued desire for change in Singapore, and the attachment to their homeland after so many years of exile.

One of the most formally intriguing films is Jane Gillooly's Suitcase of Love and Shame (2013). Having bought a suitcase on eBay full of audio tapes from the 1960s, Gilooly discovers a secret love affair preserved by these. Using the tapes to reconstruct both a story and the two characters, we hear the intimate thoughts of this couple (Tom and Jeanne are presented only through their pillow-talk voices; he is married with kids and she is single.) over several years. The visual track features two vintage reel-to-reel tape recorders—one white and one dark, to represent each character—intercut with a collage of images evoking the period. Suburban Midwest houses in a town, changing seasons and daylight and night scenes flow by as the tale of secret passion and adultery unfolds. There is an obvious fascination for viewers in hearing such intimate details of a love affair, and we cannot help but try to imagine this couple. At the same time we are almost embarrassed to listen, since these are presumably "real" people.

Discovering that Gillooly actually created some of the conversations when Tom and Jeanne seem to be together in the same location is thus a bit of a shock. It raises the question of how much of what we have heard is invented and whether there is any "documentary" aspect to the film. As Gillooly shared at the post-screening discussion, "So much of the film is about who is listening, who is witnessing, and where the audience is located—are you inside the film? Outside the film?"

Another aspect of the hybrid documentary form appears in the striking work of Amie Siegel, who creates installations as part of her film work. In Black Moon (2010), a group of oddly beautiful women dressed as combat soldiers appear to be on patrol, roaming through a landscape of deserted houses. There is no dialogue, and for much of the episode the camera creates an impression of suspense, although little happens. The punch line, so to speak, arrives at the end, when one soldier picks up a discarded magazine from the ground and suddenly discovers fashion photos of her and her companions. We learn that Siegal had hired fashion models for the shoot, insuring an odd disconnect between the "action" and the participants. Similarly in Winter (2013), which Siegal shot in a striking New Zealand house by a famous architect, the characters are all actors attired in draped white clothing. A variety of silent encounters among the inhabitants ensues and eventually one woman goes off on her own. Finding another unusual house, she stays for a while, and one morning a raft with three dead bodies appears on the river out front. Rolling the bodies into the river, she gathers her things and departs with the raft into the mist. Suggesting various temporal and cultural conditions of instability, stripped of narrative explication and causal explanation, Winter plays like dreamy science fiction.

When Siegel shows these pieces in a gallery, they are accompanied by a soundtrack. With Winter the soundtrack was performed live, its content ranging from composed music, appropriated film scores, laptop-generated electronic sounds, voiceover texts and ADR dialogue on a timed schedule.

Siegel's work seems to take us to the edge of documentary definitions, and is certainly part of what curator Dennis Lim calls "the long view." He explains, "If you take the long view, documentary is in no way a monolithic form. As a photographic medium, cinema has always had a privileged and complicated relationship to reality, and some of the most radical films in the history of the medium are precisely those that tackle that relationship in some way—documentaries, in other words. "

Wanda Bershen is a consultant on fundraising, festivals and distribution. Documentary clients have included Sonia, Power Trip, Afghan Women, Trembling Before G*D and Blacks & Jews. She has organized programs with the Human Rights Film Festival, Brooklyn Museum and Film Society of Lincoln Center, and currently teaches arts management at CUNY Baruch. Visit www.reddiaper.com.

Homecoming Jubilee: 'We Always Lie to Strangers' Bows in Branson

After more than a year on the film festival circuit, the directors of We Always Lie to Strangers finally brought their feature-length documentary about Branson, Missouri to its de facto hometown.

The Branson premiere, April 27, was a homecoming of sorts for co-directors David Wilson and AJ Schnack. The two made their first filmmaking trip to the small Ozark town in November 2007. Five years later, they returned to screen their rough cut for the four families featured in the film, all performers in the live music shows that dominate the Branson strip, often called the Las Vegas of the Ozarks.

"The town of Branson plays a pretty large role in the movie, so showing it there felt like such a milestone for us," says Wilson, co-founder (with Paul Sturtz) of the Columbia, Missouri-based True/False Film Festival, which draws documentary filmmakers from around the world.

We Always Lie to Strangers premiered at the 2013 South by Southwest Film Festival, where the filmmakers won a special award for directing. It then went on to play at festivals in Nashville, Dallas, New York and St. Louis, where Schnack, who grew up in the area, received the Charles Guggenheim Cinema St. Louis Award.

While some of the performers traveled to the various film festivals over the past year, the Branson screening was the first time they all attended together. In honor of the occasion, Wilson and Schnack invited family and friends to join in the weekend activities so they could meet all of the subjects and see Branson.

Both a setting and a character in the film, Branson is home to roughly 10,500 people, but plays host to more than 7.5 million tourists each year, many of whom also come for the region's mountains, caves and Table Rock Lake.

When CBS' 60 Minutes aired a two-part segment on the town in 1991, journalist Morley Safer called Branson the live music capital of the world, a description that stuck-as did his description of its hillbilly culture in the "buckle of the Bible Belt." His segment featured Mel Tillis and the Presley family of Presleys' Country Jubilee, the first show launched on the main drag of Branson, known as Highway 76.

After the Presleys built their theater in 1991, Branson continued to boom. The late Andy Williams was the first non-country act, and he later opened his Moon River Theatre there; the Osmond Brothers, Wayne Newton, Bobby Vinton, Ray Stevens, Roy Clark and Tony Orlando followed and also built their own theaters.

Today there are 50 live music venues on the strip; recent years, though, have seen economic struggles, as evidenced by empty theaters and declining ticket sales.

Wilson and Schnack chose to tell Branson's story cinema vérité style through specific performers, like the Presley family. Raeanne Presley, who's married to drummer Steve Presley, one of the brothers who own the show today, is the first female mayor of Branson and has a prominent role in the film. Then there are the Lennon Brothers, siblings to the famous Lennon Sisters, who appeared on The Lawrence Welk Show for 13 years. Bill Lennon, his wife, Gail, and siblings Dan and Joe moved from Los Angeles to Branson to perform in a long-running show on the strip, and stayed. Other characters in the film include the Tinoco family, who struggle to keep their Magnificent Variety Show alive, and Chip Holderman, a gay performer trying to raise his two sons in Branson.

"Earning our subjects' trust took us a long time because they were leery of how Branson had been portrayed in the media and what we would do in the film," Wilson says.

The film's title, We Always Lie to Strangers, comes from a 1950s book of the same name by Vance Randolph, who shares his observations about the people living in the Ozarks. He witnessed the locals often telling "tall tales and exaggerated stories to 'city slickers'," and when he questioned them on why they did this, they'd respond, "We always lie to strangers."

"Even though the Presleys perform almost every night of the year and have their public face, they're actually really private and what you see in the show isn't always who they really are," Wilson explains.

So, to kick off the We Always Lie To Strangers homecoming weekend, on Saturday night, the cast and crew attended Presleys' Country Jubilee. Today the 47-year-old live variety show continues to be a big draw with its mix of classic country tunes from Patsy Cline and George Jones and patriotic and gospel tunes and sometimes-corny comedy bits. Although it's definitely a bit out of touch with more liberal values, there's a lot of talent up on that stage beneath those sparkly costumes, and the Presley family gives their audience what it wants.

After the show, the group headed to the Rowdy Beaver, a bar on the strip. Driving down the strip after the shows let out, it was bumper-to-bumper traffic rolling past all the other businesses and the Indian, Thai and Sushi restaurants that have sprung up alongside regular attractions like the Titanic Museum and the New Shanghai Circus Acrobats of China.

The hotel room in the Hilton Convention Center in downtown Branson offered a view of The Landing, an upscale outdoor mall development on the banks of Lake Taneycomo that opened in 2007. The fountain show there was designed by the same company that created the one at the Bellagio in Las Vegas.

Prior to the screening on Sunday afternoon, The Missouri Film Office, part of the Division of Tourism, hosted a small brunch at the Worman House at Big Cedar Lodge, which has been featured in Travel + Leisure. We had a great view of Table Rock Lake. "A.J., Nathan and I met here on many Sundays and spent many hours relaxing and talking about the film and what we were going to shoot," Wilson recalls.

Holderman was the first person the filmmakers interviewed during their initial visit, and in 2008 they rented a condo for six months and immersed themselves in Branson culture. Nathan Truesdell, a native of Clark, Missouri, who also graduated from the University of Missouri, joined the team in early 2009.

Matthew Mills, a graduate of University of Missouri and Stephens College and founder of SpaceStation Media, made an initial investment, which expanded during the filmmaking process. He serves as executive producer of the documentary along with Vicky and Willy Wilson, Chad Benestante, Peter Schneider and Sarah Riddick, who grew up in Jefferson City, the state capital, and whose son, John Wright, is a state legislator.

The filmmakers made regular trips to Branson throughout 2011, and The Hilton Convention Center offered them a deal on rooms.

By late 2011, Schnack began editing more than 400 hours of footage. Given other films on his docket, including Caucus, which follows eight Republican nominees leading up to the 2012 Iowa Caucus, that process took about a year. Wilson and Schnack then took a rough cut of the film to Branson Visitor TV and screened it for the subjects. While the filmmakers were nervous, after the credits rolled they uncorked champagne in celebration.

The grand premiere screening filled three theaters at the Branson IMAX Entertainment Complex. Seeing the documentary after spending time with the subjects was a bit strange, given the seven-year production period. Tamra Tinoco's daughter, for example, a toddler in the film, is now 10 and looking all grown up.

So much had changed, in fact, that the film almost needed a coda. Gail and Bill are now part of the Lennon Cathcart Trio, along with Peggy Lennon's son, Mike, and they sing music made famous by Peter, Paul & Mary and The Beach Boys. In the film, Bill has short hair, but now, in keeping with the era of the show, he's sporting a pony tail. Dan Lennon and his wife now live in Columbia, and he serves as the Deputy Director of Strategic Communications for the Missouri Division of Tourism in Jefferson City. Holderman no longer lives in Branson.

As Truesdale said at one of the Q&As, "Life goes on; we just stopped filming."

After the screening, Gail and Bill Lennon hosted a wrap party at their house, and the musicians held an impromptu jam session. Steve Presley drummed while Dan played guitar along with Peggy Lennon's son, Mike. Joe, Bill and Gail sang. Other members of the Presley show were there, too, including Cortlandt Ingram on the fiddle. Tamra Tonoco sang the Patsy Cline classic "Walking After Midnight." Even Schnack got into the action, performing the Billy Joel song "She's Got a Way."

"This was the first time we had all been in one place, and it was a beautiful moment and one that happened entirely because of the film," Wilson enthuses.

The next day, Schnack and Truesdale headed back to Iowa, where they are shooting a series on mid-term elections. After the Branson premiere, the film opened at Ragtag Cinema, the art house cinema in Columbia that Wilson co-founded.

"It's been a thrilling week for me," Wilson exclaims. "Showing the film in Branson, hometown of the film, and then showing it in Columbia, my hometown, at a theater that I helped start made for a very emotional weekend."

We Always Lie to Strangers is available on iTunes and comes out on DVD June 3.

As a child, Shelley Gabert, a native of Mid Missouri, loved spending Saturday nights watching Lawrence Welk with her great-grandmother, Grace Gabert, who loved the Lennon Sisters.

At the Tribeca Film Festival, good luck trying to get a bead on the kind of longform documentary you'll find. It could be a hard-hitting, alarming doc like James Spione's superb Silenced, which describes the Obama-era prosecution of whistleblowers as leakers and even potentially terrorists. Or maybe it's a poetic meditation, like Andrew Renzi's deliberately slow-film-style Fishtail, in which you trudge along with cattlemen birthing calves in what seems like real time as both poetry and music cast the experience as art. Possibly it's a sturdy, no-surprises HBO doc like All about Ann: Governor Richards of the Lone Star State, by Keith Patterson and Phillip Schopper, entertaining largely by virtue of archival footage of Richards' own awesome speeches. Or it could be a warm, nostalgic portrait of a legendary musician, Alan Hicks' Keep On Keepin' On, which won the Best New Documentary Director Award, as well as the Audience Award.

The eclectic nature of Tribeca is baked in; it was started as a fest intended to revitalize lower Manhattan, post-9/11, and has been evolving slowly toward a stylistic and thematic identity. This year, the festival boldly made a claim (for which it will have to fight other fests, including SXSW and Sheffield) to be the center of storytelling innovation, in heralding its second half as "Innovation Week." Nonetheless, the longform docs were a mix of tried-and-true and innovative.

Some films picked up on hot topics. Among the remarkable documentaries showcased at Tribeca this year were films about surveillance and dissent. On this all-too-relevant theme, the films picked up different facets of a problem so pervasive it threatens to sink citizens' optimism in the core features of democracy. "It's easy to despair," says Silenced's Spione. "They're listening to everything we say. But I didn't want to make that movie. I wanted to feature several people who were idealistic enough to actually believe in the democratic promise—real patriots—to do what hundreds of their colleagues would not: blow the whistle." His character portraits are also journeys into hell for his characters, charged with spying and threatened with loss of fundamental freedom. "I want us to ask, ‘What country are we living in? Do we recognize this as a democracy?'" Spione maintains.

Johanna Hamilton's 1971, with Laura Poitras on board as co-executive producer, showcases a protest group's burglary of a regional FBI office, where documents pointing to the infamous COINTELPRO program first surfaced. The film has bold echoes with today, as Hamilton notes: "Perhaps we're poised to contribute to the national conversation started by Snowden. Forty-three years ago, these people did the same thing. The government was functioning in secret. If they had been caught, they would have been called traitors. With the hindsight of 43 years, it's much easier to see them as patriots. If they are the safe space to embark on that conversation, then I'll be incredibly happy." In the curiously cool HBO doc The Newburgh Sting, David Heilbroner and Kate Davis tell a story that is getting disturbingly familiar: of FBI entrapment, targeting the poor and hapless among US Muslim religious communities.

Tribeca programmers found some impressive examples of cinema vérité worldwide. Despite its default status, cinema vérité stylistically remains difficult to do compellingly. How compellingly? Well, Belgian filmmakers Sabine Lubbe Bakker and Neils van Koevorden managed to get me to watch 85 minutes of two middle-aged, lonely Belgian drunks in an on-again/off-again relationship, and not even complain. Oh, and the filmmakers also won the Best Documentary Editing award. French director Frédéric Tcheng is on a roll with his third high-fashion documentary, Dior and I, charting the eight-week-long creation of the debut collection of the unlikely new Dior house head, Raf Simons. Even if you're a fashion Luddite, you will care about the people and the process. In fact, Dior and I might be one of the better workplace stories I've seen, in terms of celebrating the labor process from cutters to models.

Jesse Moss' The Overnighters, familiar from other fests, continued to trouble and provoke with its almost too intimate portrait of a wrenching conflict in a boomtown. Should a Lutheran congregation open its doors to the wretched of the earth looking for a second chance in the new oilfields? The pastor says yes, his wife says I guess so, the congregation mostly says no. The tensions erupt into revelations that destroy lives. The camera is there for everything, including scenes that made me wonder if even I should be present. Tomorrow We Disappear, by first-timers Jimmy Goldblum and Adam Weber, creates instant nostalgia for a community of exuberant and astonishingly talented street artists whose neighborhood is facing inevitable extinction in Delhi. Kevin Gordon's True Son, about a political contender in blighted Stockton, California, features a powerful character whose optimism and savvy give hope to local politics.

Orlando von Einsiedel's Virunga is a majestic and tragic portrayal of the cost of political crisis in Congo, by following quietly heroic national park rangers (the head of whom recently survived an assassination attempt). They defend the park and its precious residents, the endangered mountain gorillas that exhibit enormous affection, wit and dexterity, against poachers and the innocent-bystander effects of brutal civil war. They sometimes pay with their lives. The film features, among other things, extraordinarily painterly portrayals of the park in landscape.

And what to do with Tonislav Hristov's Love & Engineering, which is already a hit in Scandinavia—and in fact part two in a trilogy? It's a step-by-step story of how one engineer tries to train his colleagues in social skills for wooing and winning women, awkwardly marrying engineering concepts to dating techniques. It's both embarrassing and fresh, labored and endearing. Of course it is: It's engineer-made cinema vérité.

Several films in the festival explored the aesthetics of the form in different ways. Both 1971 and Silenced interwove re-enactment, interview and vérité. Spione says of his choice of a bold black-and-white, stylized look for Silenced's re-enactments, "I wanted you to know this was a re-enactment. I pushed the style in a black-and-white, noirish way, so you would know this is about memory, but more than that, to see that this is a very threatening place. They were going into the shadow world, the heart of darkness. As an artist, it was important to me to take people where they hadn't been, and also where they didn't want to look." Johanna Hamilton, who worked with a team of fiction film people headed by Maureen Ryan, wanted a different experience: "I want people to live in the story, for it to be seamless. We used color and lighting as the trigger to bring you back into memory. It's not overt but it has its own look."

Regarding Susan Sontag, an HBO film by Nancy Kates, stood out for the complexity of its portrayal of a difficult character. John Haptas' editing was striking for its nuance, its communication of overlapping meanings, and its return to the theme of Sontag's technique of hiding in plain sight. It won a Special Jury Mention. Marshall Curry's Point and Shoot, which won the Best Documentary Feature prize, thoughtfully and wittily re-uses footage shot by Matthew VanDyke, a middle-class young man from Baltimore who tries to come into manhood by joining the rebellion in Libya, to tell a reflexive story about representation and reality.

The journey doc had a respectable showing at Tribeca. The Search for General Tso, by Ian Cheney, follows the director on a quest to discover the origins of this favorite dish in Chinese-American restaurants. In the process, Cheney discovers (partly through research done by Jennifer 8. Lee in her book The Fortune Cookie Chronicles) not only that General Tso's Chicken is not popular outside the US, but also that racism against Chinese-Americans is remarkably persistent and endemic. The evolution of Chinese-American restaurant practice maps nicely onto waves of persecution. Sounds tough, but instead the film remains wryly winsome. How did Cheney achieve a comic tone on a hand-wringing topic? "I think it's my sensibility," he maintains. "The premise is inherently quirky. We tried to set that tone in our interviews too."

Another even sunnier journey was Brent Hodge's A Brony Tale, following voice-actor Ashleigh Ball, who plays two of the My Little Pony animated cartoon characters, on a journey into fandom. For reasons the film actually cannot adequately explain (although it tries), My Little Pony attracts thousands of mostly hetero, mostly adult men, who form a passionate fan base. A Brony Tale was picked up on the eve of screening by the new Morgan Spurlock Presents series, a joint venture of Spurlock's Warrior Poets, Abramarama and Virgil Films that will showcase niche docs in a targeted theatrical rollout before releasing them on cable VOD. The other fandom film was Daniel Junge and Kief Davidson's Beyond the Brick: A LEGO Brickumentary, a relentlessly upbeat, corporate-approved view of crowdsourced creativity in toy innovation.

Other films would have to reach to find a place under the innovation umbrella, although they found their friends easily. Mala Mala, by Dan Sickles and Antonio Santini, could lay a claim to innovation largely on the basis of the subject matter: transvestites in Puerto Rico organizing to defend their rights. Jessica Yu's Misconception, comprised of three mini-docs, defies the conventional wisdom that population growth is a problem. Sam Cullman and Jennifer Grausman's Art and Craft is a well-told crime tale about a forger with a true passion for copying.

As usual, there was furious media speculation throughout the festival about sales, as the informal marketplace heated up. One thing seemed certain: The highest sales figure would go to Beyond the Brick.

Patricia Aufderheide is University Professor of Communication Studies in the School of Communication at American University, director of the Center for Media and Social Impact there, and author of Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press).

Immersion, Integration, Interactivity! Tribeca Insights

Interactivity ruled at Tribeca's Innovation Week, whether at Games for Change, the scruffy gamers-for-good conference that was folded into Tribeca activities this year; Storyscapes, the showcase for interactive projects; the mobile apps hackathon; or the all-day Tribeca Interactive Day conference. It even shone at the Disruptive Innovation Awards, where the business folks run things.

Links between the old world of linear storytelling and the interactive one are still evolving at Tribeca. At Games for Change, while Tribeca's Jane Rosenthal optimistically said, "We're all in this together," gamer speakers said things like, "Movies, the most important medium of the...20th century!" The Entertainment Software Association rep made a point about the rising importance of games by saying, "Once House of Cards' Frank Underwood is a gamer..." Storyscapes, the mobile hackathon and the TFI Day conference were standalone events, whose links with the film festival were hard to determine from the outside.

But there was plenty for mediamakers to learn.

One common theme was: Listen to the users, and take notes. At the interactive conference, keynoter Kenyatta Cheese nearly did headstands making this point. Your users are now your collaborators. And that's a good thing. "The most profound shift in entertainment is the visibility of the audience," he said. New Art Axis' Wendy Levy admitted to discomfort at ceding control—"Successful collaborations always come with a sense of loss," she allowed—but she argued that the rewards, such as the storytelling provoked by the photographic project The Oakland Fence, were unattainable any other way.

Speaker after speaker in panels and conferences argued the need for research. Whether it's a game or a film, don't try to help people without getting their own opinion about what the problem is. E-line Media's Alan Gershenfeld provided advice as useful to filmmakers as gamer designers: Understand the constraints your potential users have for adoption; your movie or game or interactive media may be great, but does it fit into the slipstream of their work, their lives, what they care about?

Another big and related takeaway: This isn't about tools, but relationships. As experiential designer Tom Igoe noted, "The things we make are less important than the relationships they support." Learning games designer Errol King argued that you're building communities with platforms, such as Beta.

But tools are useful, when you have an idea of what you want to do with them. Sympler lets techo-idiots edit video into finished works. Harv.is lets people provide instant, aggregate-able feedback without elaborate polling hardware. Beta takes a lot of the pain out of coding.

Measurement for social impact continued to drive everyone crazy. While funders are eager for better metrics, some filmmakers chafe at the idea that everything their art accomplishes can be measured. But the conversation is getting more sophisticated. In gaming, a team including researchers Ben Stokes and Tracy Fullerton created a set of categories that they hope to add to via crowdsourcing to better direct the conversation. In interactive documentary, as Mozilla's Ben Moskowitz pointed out, data provides creative opportunity—crucial feedback to foster real and better conversations with users.

Interactive documentary, the most spectacular examples of which were on display at Storyscapes, is still an expensive and experimental medium, but a fascinating one. This year the push was for immersion. Canada's National Film Board, the best funded outfit for the medium in the world, came in with an ambitious project, Stan Douglas' Circa 1948. An elaborately programmed iPad experience, it was also, at Tribeca, a room where you could spookily inhabit a virtual space and hear ghosts talking to you about a lost past in Vancouver. Perhaps the most impressive achievement of the virtual space was that users could visit without added hardware, such as Oculus Rift (which was also on display). Nonny de la Pena's Use of Force showcased the power of immersive media to dramatize and create empathy, in the story of the murder of an undocumented immigrant by border control agents. Nathan Pennington's Choose Your Own Documentary, in which a standup comic (Pennington), with help from documentarians, takes audiences on a choose-your-adventure narrative, had the virtues of live performance combined with video and polling technology.

Patricia Aufderheide is University Professor of Communication Studies in the School of Communication at American University, director of the Center for Media and Social Impact there, and author of Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press).

Full Frame Earns Renown as Filmmakers' Festival

By Angelica Das

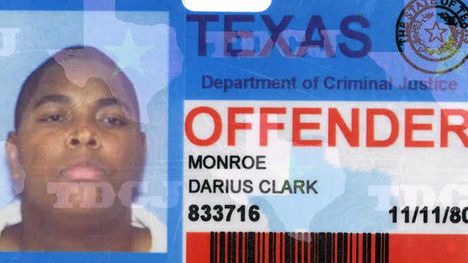

Full Frame Documentary Film Festival earned its reputation as the "filmmakers' festival" by becoming a showcase for powerfully intimate stories, most often about people. "Character-driven" can be a redundant quality when it comes to most modern documentaries, but Full Frame distinguishes both its films and its own character as "bold, personal and very brave." This was how programming director Sadie Tillery introduced Darius Clark Monroe's Evolution of a Criminal, which went on to win both the Reva and David Logan Grand Jury and the Center for Documentary Studies Filmmaker Awards.

Evolution didn't stand out in originality as much as it did in the filmmaker's willingness to face his demons. A recent NYU graduate, Monroe kept the story of his film from his own professors for fear of judgment. He turns the camera on himself and his family to challenge their collective remorse in his decision to rob a bank with two others at age 17. While engaging in his own moment of self-definition, Monroe succeeds in a much larger mission of challenging audience assumptions of what it means to be a convicted felon.

Challenging assumptions about character was a connective thread, whether it's the character of a criminal or, in the case of Doug Block's feature, the character of marriage. The opening night audience met 112 Weddings with such uproarious laughter that at times it drowned out the audio. After years of turning the camera on himself and on his family, Block turned to one of his sources of income: wedding videos. The result: "Happily ever after is complicated." Couples of varying ages revealed comical and sometimes deeply painful challenges to the reality of married life, particularly with the addition of children. For Block as a wedding videographer, the biggest moment for his subjects was when they turned and faced the world for the first time as a married couple. 112 Weddings takes us on that journey.

For one minority in America, the challenge is squarely in the journey to the wedding itself. In an appropriate bookend to opening night, Saturday evening's Center Frame was The Case Against 8, about the first federal marriage equality lawsuit to reach the Supreme Court. The film opens on a snowy day in March 2013 outside the US Supreme Court—a scene familiar to most news consumers. But the real story lay in 600 hours of footage shot over five years. That story is of two unlikely lawyers and two daring couples who were willing to make their lives public in order to overturn Proposition 8 in California. For Kris and Sandy, Proposition 8 meant receiving a letter declaring that their previously legal marriage no longer existed. For Paul and Jeff, not being able to get married meant they were second-class citizens. Both couples are now legally married.

The swell of victory for the marriage-equality lawsuit was bittersweet for the North Carolina audience, where same-sex marriage is banned. Directors Ben Cotner and Ryan White made it clear that the real vision for their film was to help turn the tide in the 33 states that don't yet have marriage equality.

This kind of communal emotional ride is part of what motivates audiences at documentary film festivals, and Full Frame has a solid local following. The Southern Documentary Fund (SDF) has been supporting filmmakers for 12 years, and four of their sponsored films were in this year's festival, including The Case Against 8. Celebrating the local is part of the substantial appeal to filmmakers, and a point of pride for the festival itself. DamNation director and Chapel Hill local Ben Knight said it had been his dream for 10 years to screen a film at Full Frame. The final day of the festival included a popular filmmaker destination: SDF works-in-progress screenings. Additional in-progress work screened alongside In Country, Mike Attie and Meghan O'Hara's finished piece on Vietnam War re-enactments in deep-woods Oregon, and a previous recipient of the Garrett Scott Documentary Development Grant.

Filmmakers also flocked to the A&E Indiefilms Speakeasy conversations. In the true spirit of Southern hospitality, these free lively discussions welcomed guests with bagels and juice in the morning, and popcorn and Moonshine in the afternoon. A regular fixture in the room was the creative mind behind the discussion topics, festival director Dierdre Haj. Haj's steadfast and guiding presence helped to solidify the collegial atmosphere of the Speakeasies.

Among the many takeaways:

• Hold off on signing away VOD rights if you are looking for other distribution.

• Your film doesn’t have to be a social-issue doc to be broadcast.

• Production value matters.

• Focus on the story, not why a funder should care about your subject.

• Vimeo is also a filmmaking community.

• You have to watch films to make films.

• Make a good movie that just happens to be a documentary.

The first of the Speakeasies was "Short Cuts," on short films, an art form much less available to theater audiences, but one in which Full Frame excels. First-time filmmaker Luke Lorentzen, a student at Stanford University, impressed viewers with Santa Cruz del Islote. Splendid cinematography immerses the audience below and above crystal blue waters surrounding one of the most densely populated islands in the world. The fisherman narrator never speaks directly to the camera; you instead see the island through his eyes, simultaneously bright and desolate. Lorentzen came away with the Full Frame President's Award.

The beauty of films like Santa Cruz del Islote is in their brevity, sometimes doing away with the narrative arch that guides features so strictly and placing the emphasis on portrait and creativity. The Chaperone, from Fraser Munden and Neil Rathbone, uses quirky animation and puppetry to tell a decades-old story of teachers at a dance that gets interrupted by a biker gang. In Steve Bognar's Foundry Night Shift, the heat of molten ore blazes from the screen as we watch in under five minutes the production of steel frames for Steinway pianos. And in another nod to North Carolina, we meet a native, Ronald, or Joe Maggard, the actor who played Ronald McDonald for 12 years, in John Dower's Ronald.

Another quirky portrait piece came from Lucy Walker, the curator of this year's Thematic Program, "Approaches to Character." Walker took guilty pleasure in programming her own short, David Hockney IN THE NOW (in six minutes). In a sweet introduction, Walker said she wouldn't be doing a Q&A because the film really says it all. She was right. With a rueful smile, Hockney tells us himself that in the end we're all just alone, as he stands with the colorful backdrop of his own landscape painting-in-progress.

The Thematic Program allows for the invited filmmaker to choose from films that span styles and decades. Hockney played with Shirley Clarke's 1967 Portrait of Jason, an exciting choice for Walker in part because it was made by a woman, and in part for the rare occasion to see a black-and-white film on the big screen. For many in that audience, sitting through two hours of Jason was too much to bear. But there was a reward for sticking out the spectacle of a man under a microscope who nevertheless lives to entertain. Portrait of Jason is a sometimes claustrophobic, but unabashed portrait of character, almost a caricature of the kind of portrait celebrated in Full Frame's new docs.

Still other portraits were inspired by the theme of family. Katy Chevigny and Ross Kauffman's E-Team is about the Human Rights Watch emergency crisis response team, but the parallel story of marriage and parenting in the midst of documenting war crimes is what glues us to our seats. In Joanna Lipper's The Supreme Price, we meet Hafsat Abiola, who modestly takes a leading role in the Nigerian pro-democracy movement, while raising a daughter, and in the aftermath of the political assassinations of both her parents. Tough Love, from Stephanie Wang-Breal, shines a spotlight on parents whose children have been removed from their homes, and their parents' battle to meet the standards to bring them back.

Character was dually embodied in the world premiere of The Hip-Hop Fellow, in which local filmmaker Kenneth Price follows Peter Touthit, better known as 9th Wonder, from teaching courses at Duke and North Carolina Central to becoming the first Harvard Hip-Hop Fellow. 9th Wonder's goal in this fellowship was to challenge assumptions about the character of hip-hop and sampling, and relate the music to the rest of our cultural history.

Full Frame creates a space in which all of these stories become a part of our cultural history, perhaps embodied by the everlasting life of Hoop Dreams. This year's tribute was to director Steve James. The "Hoop Dreams at 20" discussion included previously unseen outtakes and revealed surprising behind-the-scenes stories that were new to everyone all these years later. Stories like Hoop Dreams don't end with the credits, and Full Frame's tribute was a testament to the staying power of documentary.

Angelica Das is the associate director of the Center for Media & Social Impact at American University, and is co-producer of the feature documentary Roaming Wild.

When I finished Bill Siegel's film The Trials of Muhammad Ali, my first thought was, "That must have been some kind of trial for Bill, on so many different levels." Siegel has a history of working on films that confront America's complicated past in ways that many people would want to avoid. In large part, Muhammad Ali is remembered for his poetic speech and powerful left hook, but his political punch was just as strong, and The Trials of Muhammed Ali addresses that cultural impact. Even with its lack of direct stridency, the film confronts mainstream ways of thinking about the past, the present and the future.

Documentary: You worked with Sam Green on The Weather Underground, and clearly there's a connection to the historical context of The Trials of Muhammad Ali. How did you get involve with this story? How did the process unfold?

Bill Siegel: The Trials of Muhammad Ali set sail again and again, in fits and starts, and like any other independent documentary film, it managed to survive its own seafaring adventure. Trials' adventure began 23 years ago in New York, where my first job in documentary was as a researcher on a six-hour series called Muhammad Ali: The Whole Story. It was an obscenely well-funded project—[the budget was] $6 million. My job was to immerse myself in this amazing archive of footage and literature and put together background information packets for segment directors. There was a constant parade of people connected to Ali's life who came through this beautiful SoHo loft, from [writer] Robert Lipsyte, whom I later interviewed for Trials; to Sonji Roi, Ali's first wife; to Jeremiah Shabazz and several others from the Nation of Islam; to some of Ali's former opponents in the ring.

It was a dream job that indeed proved too good to be true: The project heads somehow managed to spend all $6 million in about a year—without finishing the film. Looking back, I call it "The Titanic." I heard Avid got $1 million and basically piloted the first wave of their edit system there. You had to laugh to keep from crying, watching all these old-school filmmakers transfer from Steenbecks to online, working for days on scenes, only to have their work obliterated when their systems crashed; they were also learning to back their work up. So Avid got theirs, and I got to know both Sam Green and Leon Gast, who were shipmates of mine. When the ship sank, Leon pulled his segment out of the wreckage and made When We Were Kings. Sam and I went on to make Weather Underground, and I hear one of the Whole Story heads is now a well-known yogi in New York. So all was not lost.

That was my introduction to documentary filmmaking, as well as to Muhammad Ali beyond the ring. I kept finding myself drawn to this footage of Ali on college campuses, gloves off, pummeling entire bodies of college students with rad speeches against the Vietnam War and against racism, representing himself as a minister of the Nation of Islam. I thought, You can't tell Muhammad Ali "the whole story," but there's a fight film right there.

Ali prays at Hussein Mosque in Cairo, June 1964, after announcing he is part of the Nation of Islam Photo: Express/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Fast-forward about 15 years. I was living in Chicago and I cold-called Claire Aguilar at ITVS. She got the idea about a documentary on Ali in exile immediately, and came in with some development money. I used it to do the first interview for Trials, with Gordon Davidson [a lawyer who helped launch Ali's career], at Churchill Downs in Louisville. While I was there, I connected with the Muhammad Ali Center and learned about this mock trial competition, where students from 30 high schools across Kentucky were utilizing trial materials taken directly from Cassius Clay v. United States (1971). Each school was required to have one student portray Ali on the witness stand. So I used the rest of the initial ITVS money trying to develop this mash-up of the mock trial and the actual Ali archival material. We followed three teams (including one from Ali's alma mater, Central High School, in Louisville) preparing for and engaging in the competition. We also shot interviews with several coaches, parents and students, giving us this whole range of multigenerational perspectives on Ali and the myriad issues that his trial raises. I cut a 10-minute demo. I still think it was a great idea, but no one with additional funding did, and the project was broke (although we do have a short called The Mock Trials of Muhammad Ali on the DVD, and we are further developing that footage as part of the educational and outreach campaign for the film).

I went back to my original idea of a film about Ali in exile, and I brought it to Gordon Quinn, founder of Kartemquin Films in Chicago. Gordon, along with Justine Nagan, Kartemquin's executive director, agreed to take it on, and they joined Leon Gast as executive producers. Via Kartemquin, I connected to Rachel Pikelny, who became producer; Aaron Wickenden, who edited; and Joshua Abrams, who composed the film score. All through the mock trial period, I'd been relying on pro bono help from Brit Hayford, a former student of mine at Columbia College; she became coordinating producer.

With that merry band of pirates, along with several others from Kartemquin and elsewhere, I became captain of my own ship, determined to avoid another Titanic. One thing was certain: We were not going to be weighed down by $6 million. We tried everywhere for funding, got to the final round of ITVS Open Call and applied twice to the NEH, but at every funding turn we battled what I came to call "Ali fatigue"-as in, "Why does the world need another film about Muhammad Ali?" Eventually, Kat White from KatLei Productions came on as an additional executive producer, and we finally broke through ITVS' Open Call, where Claire had never wavered in her support. She was joined by Lois Vossen at Independent Lens, and later Orlando Bagwell, then at the Ford Foundation, as true champions of the film. I'll be forever grateful to, as well as astounded and humbled by, the list of funders that appears at the end of Trials. For most independent documentary films, that part of the credits is as long or longer than any other part. For Trials, the list has five names.

D: The first big question in the film comes from Minister Louis Farrakhan, in reference to a repeated refrain from Ali: " 'Still a nigger.' What did my brother mean?" How did you land on this as a way to begin the film, and what did you mean by it? Was this the central question of the film for you?

BS: The beginning of the film has three elements: The David Susskind clip from 1968, where Susskind is on a couch in London, excoriating Ali, who is trapped inside a black and white television because he's in exile in the States, having been stripped of his passport. Then there's the 2005 clip of President George W. Bush giving Ali the Medal of Freedom. And there's Minister Farrakhan giving his commentary on the Bush clip. Taken together, the opening scene is meant to frame the film's journey for the audience, as well as pose a central question: What does this journey say about us? So to me, it's more than Farrakhan's question, because I see Farrakhan's question as rhetorical.

D: To follow up on that question, names, as a framing device, seem to be as important a theme to the film as the idea of a trial. Eight minutes after Farrakhan's question, there is a clip of Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, asking,"Why are we called Negroes?" Then, at 17 minutes into the film, a 10-year-old Kallilah Camacho rips ups his autograph and says to him, "When you learn who you are and you don't have the white man's name, the slave name, then you come back and talk to me when you know who you are." Clay is of course stopped in his tracks by this-and he later marries her. I would even go so far as to say that she is one of the heroes of the film. Can you talk about the significance of names in the film?

BS: Names are an introduction to our identity. They don't completely define us, but they do introduce us. The world was introduced to Muhammad Ali as Cassius Clay, and he took a new name as part of finding himself in the world. And because Cassius Clay had already established himself as a force to be reckoned with, it was on the rest of the world to reckon with his new name. The film aims to show how some corners refused to even acknowledge it, while others were simultaneously inspired by it, or became part of the movement that gave it to him.

As a storyteller, I'm driven by the question, "How do you get to be to who you are?" Everyone comes into their own differently, and in doing so comes to establish their identity. (That said, I think we're all forever works-in-progress.) I think it works collectively too. "We the people," call ourselves "The United States of America." One of my favorite lines in the film indeed comes from Khalilah, who I do think is an heroic force of nature, when she says, "Growing up in the Nation of Islam was extraordinary. We were living in a nation within a nation, which is this nation." It's complicated, right? I certainly believe the USA is still coming into its own. We're still trying to figure out who and how we want to be in the world and I think that's true for the Nation of Islam as well-or as Farrakhan says about Ali, "Constantly evolving, constantly changing..."

D: Names come up once again when Kallilah explains to him over the phone, "Once you sign your name to that paper, you are their slave forever. So just don't sign it. Say 'Hell no, I won't go.'" How did Kallilah come to play such a strong role in your telling of the story? How did you gain the trust and respect of people like Kalilah and Salim Muwakkil?

BS: From the beginning, I drew up a short list of people I had hoped to interview. In addition to focusing on Ali beyond the ring, another way I aimed to distinguish this film (and combat "Ali fatigue") was by only interviewing first-hand sources, people who were there and have had a principal role in Ali's life: his brother, his wife during exile, people central to his relationship to his faith, to his development as a person. No historians, no academics-no disrespect to those folks, but it isn't hard to find people with something to say about Muhammad Ali. In the end, I got everyone on my list except [basketball Hall of Famer] Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, but his refusal led me to [former track star] John Carlos, who I love in the film and more so in life.

I first met Salim in the late 1980s, when he was a staff writer at In These Times and I was interning there right out of college. We'd crossed paths over the years since then, just enough for him to remember me, to let me buy him a cup of coffee. His agreeing to do an interview was instrumental. I'd done the one with Gordon Davidson and had amassed a decent amount of archival screeners before going into the mock trial period. Salim lives in Chicago and Kartemquin covered the shoot cost. From there we were able to break the project through to ITVS Open Call funding the second time we went for it, in summer 2011.

Once we had that funding, things moved pretty quickly. [Producer] Rachel Pikelny researched and brought in a whole new wave of archival footage, and I went to work on the rest of my interviewee list. Robert Lipsyte, as I said, I'd met during the Whole Story project. By the next century, he'd published his memoir. I was in New York when he was doing a reading at a Barnes and Noble. I crashed the green room and reintroduced myself, and he laughed and said, "I feel like we've been through combat together." I had learned about Tom Krattenmaker's Supreme Court role during the Whole Story time too, and I had tracked him down then. In fact, we interviewed him for that film, but that footage went down with the Titanic. Tracking him down a second time was much easier, thanks to the Internet.

Finding Khalilah took a long time and it's a long story, but once I finally got her phone number and called her, we clicked immediately, mainly because Khalilah clicks with most of humanity. I believe in pre-interviewing, ideally in-person, not only to see how a potential interviewee might work—hearing what kinds of stories they have to tell and how they are at telling them—but also to let them lay eyes on me. I mean, Who am I to tell this story? Why do I want to tell it? Am I driven by an ideology, or curiosity? If I'm going to ask someone to do an interview on camera, they deserve a chance to suss me out, ask me anything they want, and we go from there. So I went to Miami and just hung out with her for a couple days. We really hit it off, and she opened doors for me that I didn't even know existed. Khalilah was instrumental not only for reasons that I hope are obvious from the film, but also because she connected me to Rachman, Captain Sam and Minister Bey and literally got me in Farrakhan's door. It's not always possible to pre-interview in person, but I spent some time with Gordon Davidson and Rachman, though not as much as I did with Khalilah. Still, in every case, I think it paid off in the interviews they gave for the film when I came back with a film crew.

D: Near the end of the film, Lipsyte says, "There are so many ways to look at him that have to do with us, but nothing to do with him." This seemed like a really important line in terms of reflecting back on the goals of the story. Can you talk about this idea?

BS: It is a key line; thanks for picking up on it. It goes back to what I said about the beginning of the film and that central question—and gets right to your next question(s). The audience always completes the picture, and every audience member completes it differently. If you are thoughtful in how you evaluate Ali, he is a cipher for enough of the last 50 years of history, for your evaluation to say at least as much about you, your morals, your worldview and your own identity, as whatever you have to say about him. Every life is valuable and everyone's story is mighty, but not everyone packs a punch like Ali. Why is that? In part, I think, because he became so fearless in his ability to throw a punch and so courageous in his willingness to take one regardless of the outcome, that he now seems to me to be completely at peace with who he is in the world—righteous, lovely, moral and true. As for the rest of us...?

The Trials of Muhammad Ali, which won the 2013 IDA ABCNews VideoSource Award for best use of news footage, airs April 14 on PBS' Independent Lens.

Michael Galinsky is partners with Suki Hawley and David Bellinson in the award-winning production studio Rumur. Their film Who Took Johnny premiered at Slamdance. They are currently working on a film about the connection between stress and pain.

It's been CAAMFest for two years now, but it's still a pleasant surprise not to have to utter its former mouthful of a name: the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival. Like its parent organization, the Center for Asian American Media, its name has been cropped, but its documentary subject matter has remained as inclusive as ever. That CAAMFest draws the youngest audiences I've ever seen at a film festival just confirms its inclusiveness—and probable staying power.

Arab-Americans are another community included in CAAMFest's documentary scope. Usama Alshaibi opens his personal film American Arab at the Chicago gravesite of his brother Samer. Samer ended up, according to his grieving mother, a shaheed, meaning witness or martyr, of "the bad poison in America—the wrong freedom, destroying yourself with drugs." From this dark beginning Alshaibi dips into other issues troubling a family whose matriarch was determined to leave Iraq and pursue the American dream, only to face divorce—and war between the two countries.

Alshaibi emphasizes this constant tension between personal and ethnic upheaval as he brings up anti-Arab prejudice, school bullying, hate crimes and media stereotyping in the aftermath of September 11. A series of images defining types of women's head-coverings implies that they pass without controversy in most cultures but stand out as the most visible and vulnerable sign of Muslim belief in an Islamophobic society, as proven in an unprovoked assault in a Chicago supermarket. Alshaibi himself plays up stereotypical Arab images with a punk sensibility, hoping to "give people a space to be complicated."

But the real test of these contested images is in Alshaibi's own life, when he and his white wife move into a "nice" Iowa town and give birth to a daughter. One night he's called a "sand nigger" and beaten and kicked in the face when he tries to enter a house where he thought a party was in progress. If that wasn't traumatic enough, the barrage of negative comments and suspicion about his motives for publicizing the assault starts taking a toll on his mental health.

Masahiro Sugano's Cambodian Son, winner of the Documentary Award, tells the saga of Kosal Khiev, one of thousands of KEAs, or Khmer Exiled Americans. Born in refugee camps after fleeing the war in Cambodia and arriving in the US as children, KEAs compromised their refugee status by committing felonies, and were wrenched from their American families by deportation "back" to Cambodia—a country they'd never lived in before. While doing life in Folsom Prison before his exile, Kosal started writing poetry and performing spoken word. An unexpected invitation to represent Cambodia in a London gathering of performance artists and poets becomes the exiled Kosal's opportunity to break out of his mental imprisonment.

Cambodian Son asks if a man who was born a refugee, never knew his father and spent 14 years in prison for gang-related crimes is up to the challenge of traveling to an unfamiliar country and performing in four cities while doing workshops and radio broadcasts. Even if he scores acclaim at the London festival, he still has no long-term career plans, and can easily fall into the rut of drugs and criminality among his fellow exiles in Phnom Penh. It's a Facebook connection with a man from his remote past that poses Kosal's ultimate test and redemption. As with other recent documentaries about Cambodian-Americans in Kosal's fix—with deportations hitting higher numbers every year—the viewer is challenged to feel compassion for a subject whose many past mistakes need to be forgiven as he struggles to forgive himself.

Veteran filmmaker Rea Tajiri's latest, Lordville, is a meditation on community memory in a historically rich but shrinking hamlet on the Delaware River. Tajiri's ownership of land there and its uncertain boundaries are the departure point for an exploration into Lordville's whispered past involving 19th century land grants, intermarriage between white men and Delaware Indian women, the erasure of the Native population, and finally the recurrent flooding that threatens to wipe out all signs of human history. Rumored ghost sightings and some labored reverse-motion footage of what looks like hipsters performing a healing ritual are less interesting than the voiceover narration by local genealogists and historians and the haunting camerawork that evokes the unwritten history of that contested land, more meaningful than just a quaint weekend getaway for weary Manhattanites.

Tibetan filmmaker Tenzin Tsetan Choklay's debut, Bringing Tibet Home, contends with a different river: the one marking the boundary between China-ruled Tibet and the exile countries of Nepal and India. New York-based artist Tenzing Rigdol hopes to pay tribute to his late stateless father by transporting over 20 tons of Tibetan soil over the borders of Nepal and India, as well as dozens of checkpoints along the way, to retrace where his parent lived as an exile. At his father's final home in Dharamsala, India, site of the Tibetan government in exile, Rigdol stages his installation, titled Our Land, Our People, by spreading the soil for Tibetans to touch, hold, walk on and weep over—eventually carrying away their own handfuls to keep.

Much of the action suffers from Rigdol's inability to do more than sit around fretting in hotel rooms and talking with fixers on his phone, but once he resorts to a risky tactic the film lurches into movement. And what at first felt like a foolhardy contrivance on Rigdol's part—endangering his oldest friend—ends in an emotional finale that makes all the bureaucratic uncertainty and peril feel worthwhile. Bringing Tibet Home likens the act of stepping on one's native soil to the ephemerality of sand painting, in which a painstaking artistic effort is "destroyed" by chanting devotees dancing on it.

Stories from Tôhoku, by American filmmakers Dianne Fukami and Eli Olson, details the passionate response of Japanese-Americans to survivors of the 2011 Tôhoku earthquake, tsunami and nuclear incident, and the relationships that have developed between them. We see what the locals have done with the $40 million that Japanese-Americans donated to them. Japanese-Americans in turn are struck by the survivors' spirit of gaman (endurance) and shikata ga nai (it can't be helped) that they recognize in their own ancestry. Especially in the older victims' resignation to living out the rest of their lives in temporary housing, the Japanese-Americans are reminded of their own grandparents, imprisoned in tarpaper shacks during the World War II internment—hardly a natural disaster, but having similar effects of displacement and feelings of worthlessness. More than anything, this film pleads with audiences to visit with survivors, and never forget.

A sadly forgotten chapter in the history of American labor activism is revived in Marissa Aroy's Delano Manongs: Forgotten Heroes of the United Farm Workers. Since the 1920s, Filipino men have picked fruits and vegetables on California farms and have organized against grower abuse. Laws that prohibited marrying white women kept them in a permanent bachelor society of gambling, prostitutes and anti-Filipino violence. In Delano, 1,500 older laborers were organized by pugnacious, cigar-chomping cannery veteran Larry Itliong, whose alliance with Cesar Chavez led to the Delano Grape Strike of 1965 and the creation of the United Farm Workers. This documentary makes a strong case for the charismatic Itliong's own cinematization alongside the recent Chavez biopic. At CAAMFest's new venue, the New Parkway Theater in Oakland's burgeoning Uptown district, this film inspired an impassioned Q&A.

CAAMFest's Special Presentations included a spotlight on documentarian Grace Lee, whose earlier films still warrant repeated viewings with their subtle and multi-layered pokes at the ethnic-identity film. Her 2007 mockumentary American Zombie (screening here) parodied the way we talk about marginalized groups with combined New Age admiration and condescension. It was also a brilliant satire of popular genres from reality TV to the zombie thriller (before they became mainstream), as Lee kept both humming to a climax that's horrifying, yet blackly funny.

An on-stage talk with Lee came a few hours before a packed Castro Theatre screening of her latest film, American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs, which also won the festival's Best Documentary Audience Award. The film kept the audience riveted to the life and times of a 98-year-old Chinese-American former Black Power firebrand who now counsels the young to reflect before they applaud. It does this with a minimum of lecturing and a great deal of respect and humor for a complicated role model. Proudly Detroit-based, Grace Lee Boggs has led a life that redefines revolution as evolution.

Although Boggs looked frailer than she does in the film and was wheeled to the stage for the Q&A, her voice and words were strong and authoritative. She demonstrated the confidence that frustrates Grace Lee the filmmaker, who tells Boggs on-screen that she can't believe Boggs doesn't doubt herself, doesn't struggle internally. There are scenes in which Boggs forcibly urges someone to rethink what they are saying, whether it's a friend's flippant remark or Danny Glover on a political point. Glover assures her, "You have me thinking!" and she piles books on him for homework. Boggs' revolutionary actions now take the form of transforming others. During the Q&A she kept referring to the changing of epochs, portraying herself as an ancient sage who can see far back into the past as well as deep into the future of the human race. She personifies the inclusive documentary impulse at CAAMFest.

Frako Loden is adjunct lecturer in film, women's studies and ethnic studies at California State University East Bay and Diablo Valley College. She also reports on film festivals for Fandor.

A film production client of mine once insisted on hiring its own local security for a shoot on location in Mexico. It was a feature film, the crew and talent were in place, and shooting was set to begin the next day. You know what happened: The following morning, the producer and crew awoke to find all their equipment missing, never to be recovered.

Foreign documentary productions can be perilous. Losing your equipment to theft is one of many risks you face when producing a documentary in a foreign country. Travel in unfamiliar, often remote locations. Unfamiliar language, customs, governments. Weather, disease, conflict. All these factors increase the risks you incur producing a documentary film on foreign soil.

As a documentary producer, you will likely use handhelds and travel more lightly than my unfortunate feature film client. But even if you don't have millions of dollars in equipment on location, you still are investing substantial money, time and talent in a foreign film production.

Fortunately, there are ways to help protect your investment: By reducing risk wherever you can, and by securing film insurance coverage in case you incur any losses. We usually recommend that foreign film producers purchase insurance to cover their equipment and content (producer's portfolio), workers compensation (covers not only your crew but also locally hired foreign workers), general liability (covers you in case of third-party claims of injury or property damage) and non-owned automobile policies (for vehicles you hire while on location).

The following tips will help you anticipate and reduce risks to your production—and make it easier for you to obtain the insurance coverage you need while traveling to a foreign country and shooting on location. In a nutshell, you need local knowledge and a detailed plan—and, as emphasized above, you must protect your equipment.

Find Local Knowledge and Resources

Rule number one for reducing risk while producing a documentary in a foreign country: Always know the territory—or work with someone who does.

"The number one thing is obviously to have local knowledge," explains JonPaul Evans, an agent/broker at The Truman Van Dyke Company in Los Angeles, who is experienced in providing insurance coverage for foreign documentary productions. "You want a field producer with local knowledge of the territory. You don't want to be in situation where you don't know what street you've turned down; you have a camera guy, grip, gaffer and other assets with you; and they're all dependent on you knowing where you are and where you're going."

Knowing the territory—and having permission to be there—is especially crucial if you're traveling into areas in conflict. Standard insurance policies typically exclude war, confiscation and rebellion, so producers who are traveling into areas at risk of conflict need to discuss their specific travel plans with their insurance agent to determine what coverage can be obtained and how. Filming in hostile countries without government permission is considered very risky and is generally not advised; in these situations, for instance, we often hear about confiscation of equipment because government authorities and other locals can be suspicious about what you're doing. However, in some cases, producers are able to mitigate their risks using military escorts and drivers, hiring bodyguards and security to protect equipment at risk.

When we are evaluating and deciding whether to underwrite an overseas production, we often turn to government resources—for example, the US and British governments' travel warning websites—that can provide in-depth and current knowledge of local countries' conditions, health, crime, entry requirements, visa issues and currency issues, and other potential hazards.

Evans typically asks his clients, "Is there a film commission in the area that can assist?" The best sources of local knowledge can be film commissions and other organizations specifically oriented to providing local support and resources for foreign filmmakers. "Film commissions offer a world of resources, everything from locations to shoot to hotel discounts in the area to insights from someone who's already shot in the area."

Producers also can contact local universities, tour groups and nonprofit charitable organizations that know the territory. These organizations can recommend drivers, interpreters and accommodations. You should also consider hiring experts to help you deal with harsh conditions. "Coming from the United States, your documentary crew won't be used to the local weather, food, water, elevations, wild animals and other local conditions that need to be taken into consideration," Evans notes.

In addition to the knowledge, there can be other advantages to hiring on location. "Often times you may get credits for hiring locals," Evans says. "A lot of people like to film in London because they get huge tax credits for filming and for hiring local people."

Have a Plan—and Stick to It

Another essential means of reducing risk—and a key piece of information for obtaining insurance—is a detailed itinerary for your foreign shoot.

"You want to have an itinerary, a plan," Evans explains. "If you have, say, six or seven people on your team, everyone needs to be together, everyone needs to be aware of the itinerary, so you can keep control of your crew and know everyone is safe. Designate someone to go over the itinerary and know where everyone is, to be the point of contact, just to know that everyone is following that order of operations in this region. Sometimes, everyone in the crew sends an email or text message in the morning and at night to say, ‘We're safe.' Otherwise you may be spending your time looking for an asset rather than filming."

The ideal itinerary is very specific and detailed. For example, one producer we worked with recently provided an itinerary that included plans for two or three producers to scout the area and look for their field producer. There was a detailed breakdown of the shoot—the itinerary included breakfast, lunch and dinner details for each day, local contacts, emergency contacts, the local driver and other information for the crew.

Protect Your Equipment

Obviously, insurance coverage is recommended for all of your equipment—but given the challenges of replacing it while in the midst of producing your foreign documentary, you also want to do everything you can to prevent damage that might delay or end production or result in unusable footage.

When in transit, for instance, "Be sure to be in contact with the airline and red-sticker your fragile equipment," Evans says. "Make sure you have all the necessary tools to use the equipment and maintain it in harsh conditions. For example, do you have proper brushes for cleaning out lenses after a sandstorm? Are you prepared for extreme heat and cold, to prevent fogging or bad footage?"

Know Who to Call When Something Goes Wrong

In addition to insurance coverage, an insurance company that specializes in covering foreign film productions will also generally provide you with emergency medical and travel assistance services. The producers and crew will be issued a card with a toll-free telephone number allowing you to obtain round-the-clock services such as medical evacuation coverage, personal security and evacuation in case of danger, and multilingual coordinators who can talk to local contacts to facilitate your care and safe return home.

ProSight Specialty Insurance specializes in providing insurance policies that cover features, documentaries, TV series, short films, webisodes and other productions.

Typical Insurance Policies for Foreign Documentary Productions

Producer's Portfolio: Documentaries don't need cast insurance, but this covers the producer, lost footage due to faulty equipment or stock, equipment including rental cameras, and extra expenses due to production delays.

Foreign General Liability: Covers property damage and injury to others.

Foreign Non-Owned Auto: Covers property damage and injuries involving the use of rented vehicles.

Foreign Workers Compensation: Provides medical care and rehab for employees injured on the job or who contract a work-related illness, and can cover both your crew from the US and third-country nationals.

In this multimedia age, discovery of new art is rare. Discovering a new artist, posthumously, is even rarer. Yet that is what happened to historian John Maloof in 2007, when writing a book about his Chicago neighborhood, Portage Park. Needing some vintage photos as illustrations, he acquired a box of negatives for $400 at a storage locker auction, but set them aside when they did not fit the subject matter. Revisiting them two years later, he realized he was looking at the work of an extremely talented street photographer.

He only had a name to go by: Vivian Maier. Upon first acquiring the negatives, an Internet search came up blank. A subsequent search two years later revealed her obituary, but with little information on who she was, or her work as a photographer. Intrigued, Maloof pursued further, following up a lead on an envelope of negatives. On the phone from Chicago, Maloof recalls, "I got an address and basically I wanted to find out who these people were in the photos, as I kept seeing families. So I called up and said, 'I have negatives of a lady called Vivian Maier,' and I was told, 'That was my nanny.' And that completely took me by surprise; I would have never guessed that this huge load of negatives, with unbelievable work, taken in dangerous areas, would be done by a nanny.

"When I met with those two brothers [who were once Maier's charges], I gave them a box of all their childhood photos and negatives," Maloof continues. "I asked them if they had any of her other stuff and they said, 'John, she was a pack rat. We have two storage lockers we are paying the monthly fees on and we want to throw it out; it's mostly junk.' And that's when I got a truck, and I loaded everything in the truck so that they would not throw it out.

"They had so many interesting things to say about her," Maloof recalls. "I thought, 'This is really bizarre and fascinating to me,' and I decided to document my journey to unravel who she was from that point."

That was the start of Finding Vivian Maier, a documentary co-directed by Maloof and veteran TV and documentary producer Charlie Siskel (Religulous; Bowling for Columbine). The film is a captivating journey of discovery of a talented, yet highly eccentric photographer, who hid her artistry from the public. The filmmakers paint an unflinching portrait of someone who is by no means Mary Poppins: unconventional, cagy, bizarre and irrational, yet gifted with an uncanny eye for framing and capturing life.