Philadelphia Story: 'Let the Fire Burn' Tells Morality Tale through Archival Footage

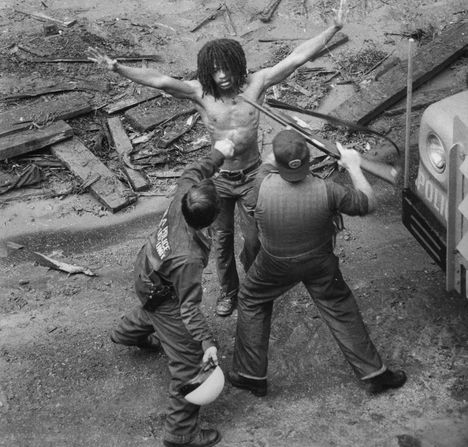

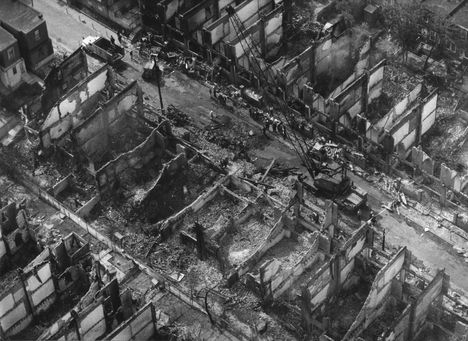

Last spring I covered the Tribeca Film Festival for Documentary magazine. I thought that the quality of documentary films was very strong. New HD cameras help to make the images sing, but the films that really jumped out at me relied heavily on archival footage. The most rigorous use of archival was seen in Jason Osder's Let the Fire Burn, which tells the story of MOVE, the radical group that sparred with the city of Philadelphia in the 1970s and '80s. The conflict culminated in May 1985, when local authorities bombed the MOVE-occupied rowhouse, resulting in the deaths of 11 people and the destruction of 61 homes.

Let the Fire Burn is comprised entirely of available footage. For me, it was the standout film of the festival—and it earned an award for Best Editing of a Documentary Feature and a Special Jury Mention for Best New Documentary Director.

I recently traded e-mails with Osder because I wanted to find out more about the film-but even more importantly, I wanted to do what I could to get others to see it.

Documentary: First, tell me a little about your filmmaking background. How did you came to work on this particular project?

Jason Osder: I developed an passion for documentary at the Documentary Institute Program at the University of Florida; this group has now become the Documentary Film Program at Wake Forest University. I can't say that I had more than a vague idea what it was all about before I went to school there, but I found a mode of communication that seemed to suit my way of thinking and fulfill a longing for expression that I can always remember having.

As for the MOVE story, it is something I remember from being a child growing up in Philadelphia. As a child, you lack the frames that most adult use to understand an event like this: race relations, or police brutality, or militarization or what have you. For me, I was just scared.

Later, when I went away to college, I remember that this event that had loomed large in my childhood was basically unknown to my peers from other parts of the country.

D: Do you think that the fact that you identified with the story, from a childhood perspective, influenced the storytelling? I ask this in relation to the nature of the deposition footage. It really exists in this strange realm where the child has an intense sense of maturity and gravitas.

JO: Absolutely, it influenced the storytelling.

I'm not sure that I would use the word maturity, but I think in a film where the audience is asked to question the truth, the testimony is sort of unimpeachable.

D: I am particularly interested in the way in which archival footage was used in the film. Can you talk me through the process of making the film from this perspective? At what point did you settle on the idea of taking a very rigorous and formal approach to the project in terms of using only archival footage?

JO: I have to give the editor, Nels Bangerter, major credit for this decision. It happened when he came on and reviewed the footage. I had shot a handful of interviews. I was not interested in interviewing a wide range of people, but getting to the heart of the story through a select group of emotionally revealing interviews with people whose lives had been changed by the events. I had shot most of the ones I wanted, including Michael Ward [who is seen as a boy in the film—and who recently died in an accidental drowning; he had been the only surviving child of the bombing.].

When Nels came on, he reviewed all of the material that I had been collecting for nearly a decade, and saw that there were special possibilities of working with the archival material, especially the hearings. He was the first to realize that we could build drama in those hearing scenes while also delivering the exposition and context that a viewer would need. There was a bit more to it than that, but the whole discussion—from suggestion to deciding to at least attempt to cut the film in this style— happened in less than 48 hours.

Once we made that one radical decision, we strongly agreed that everything else about our approach should be formal, rigorous and classical.

D: The lack of mediation really works. It takes the footage out of both its social structure and the current one. I was recently talking to Chad Fredrichs, director of The Pruitt-Igoe Myth. He is thinking he will only make historical films using entirely archival footage from now on. What's next for you?

JO: Actually, I am looking at another incident from 1985—the assassination of an Arab-American activist named Alex Odeh.

It is still early, but it looks like an opposite approach: exploring the relationship between past and present more overtly by focusing on the present-day efforts of activists trying to get the unsolved murder taken more seriously by the Justice Department and the FBI. It is likely that the historical mystery will be revealed through observational shooting of the present-day investigation .

D: Most people who see a film aren't going to have any idea about the amount of work that went into it.

JO: Well, that is always true, and in a sense, it is what we are going for. A film should feel effortless, like there was no other way it could have happened . . . but I get your point.

D: That is, it isn't simply a matter of getting some tapes, going through them and putting it all together to make "sense" of the story. Can you tell me about the thought process that went into choosing and working with this subject matter? What I'm looking for is something that talks about the ideas in relation to race, power and media—that in some ways can most effectively be dealt with the critical distance of both time and in a way separation—that feels like it could only have been done in this manner using only archival footage.

JO: Well, this is the only way to make this film, but there are other films to be made that would say something different about this subject matter. There are storylines and themes that fell away, partly because we decided to use an all-archival approach.

I think the strength here is that it becomes a morality play. I think it will be "timeless" in the sense that it will always seem to say something critical about the present day. It will not date in the way a film with interviews or narration always places itself in the time it was made. This is placed in the time that it happened—like a stage play. There are also valid criticisms for doing it this way.

I also think audiences are changing. They are hyper-sensitized to manipulation. This sort of pastiche approach is a way to defuse some of that suspicion.

Finally, it was always a puzzle with this story: how to represent a "truth" that is so fraught with conflicting versions? In the end, using the archive is a way that the viewer was always aware that they were seeing a perspective reframed turned out to be the best answer to that challenge of representation. Every piece of footage already had an agenda before it was part of our film; the viewer knows and needs to grapple with this.

Let the Fire Burn opens October 2 at New York's Film Forum through Zeitgeist Films, with openings across the country to follow through December. For more information, click here.

Michael Galinsky is partners with Suki Hawley and David Bellinson in the award-winning production studio Rumur. They are currently working on a film about the connection between stress and pain.

From Marta Cunningham's Valentine Road. Photo: Dawn Boldren.

In February 2008, a day before Valentine's Day, a 14-year-old boy in Oxnard, California, killed his 15 year-old classmate with two gunshots at point-blank range, in a middle school classroom. Brandon McInerney murdered Larry King after King had asked him to be his valentine.

When filmmaker Marta Cunningham heard about this story, she became obsessed with it. Cunningham amassed 400 hours of footage from four years of filming to create her first documentary, Valentine Road, which premiered at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and won the Outstanding Documentary Award at the Frameline San Francisco LGBT International Film Festival. Cunningham spoke with Documentary about her inspiration for the film and her hope for outreach and education.

How did you first hear about this story?

Marta Cunningham: I read a very short article in the Southern Poverty Law Center's magazine, and I was horrified and blown away that this had happened in California and I had heard nothing about it. It was something that I can honestly say rarely happens to me, but I read it, called the person who wrote the article immediately, and she told me I should get in touch with Casa Pacifica [a residential center for abused and neglected children], where Lawrence was living when he was killed, and from there, I went to Brandon's hearings and started filming his friends and whomever I could talk to who knew him.

I was just obsessed with this story. I wanted to know how someone so young as Brandon could develop this kind of hatred for someone who was so courageous and outspoken and free in himself. And it was mind-blowing to me that this had happened in California. I was born and raised in Northern California, and I'd always thought of California as a state that was much more forgiving and accepting of difference. I think I was idealistic to a certain degree; I had traveled the world and by this point I had two children, and I just was really angry about [this story]. It really angered me deeply that this wonderful child, who is biracial and who seemed to be exploring his gender identity, was so misunderstood and hated by his community—not everyone in the community, but most of the people who knew him at the time.

It was a snowball effect: The more I found out about Lawrence, the more I wanted to just dive in to really uncover who he was, and the more I found out about Brandon, the more I wanted to find out who he was and where he came from and what kind of mindset this child was living in, to kill a human being? What was his environment like, that put him in this mindset?

Do you think part of why this story resonated with you is because you are a parent?

I think being a parent had a huge part in the responsibility I feel toward my own children, but also just children in general. I think that if we don't speak up when we see these types of injustices, then how dare we have any kind of say in what we want in our world? Both of my parents were activists and teachers, so I was raised with a very strong sense of voice, and here I saw this child who had this incredible gift of having a voice in being different, and it was extinguished far too young. It just hit me to my core. At the time, I was thinking about going to film school and I felt, "I have to tell the story now." I first thought it might be a narrative film, but I realized, "This is a documentary and we have to start shooting right now."

Were there moments when you struggled emotionally to make this film?

Emotionally, it was a very difficult space to live in. I think the most difficult aspect of it was talking to people who had post-traumatic stress disorder and didn't know that they had it. I had to ask myself many times where my boundaries began and ended and where theirs began and ended, especially with the children. I was basically watching them unravel, and I didn't feel, on a moral or ethical basis, that it was okay for me to continue filming while they were in this state.

So I found therapists for some of the kids I interviewed, and they're still in therapy and they're doing really well. That was the toughest thing for me to do: to say, "How can I continue filming these children when they're unraveling before my eyes and I know the reasons why they are, and they don't really know?" I remember asking Mariah at one point, "Do you know what post-traumatic stress disorder is?" And she said, "No, I don't." So I said, "Will you do me a favor and ask the counselor at school?" They had group counseling at school, and so the next time I saw her, she said, "I asked her about it, but she said she didn't know a lot about it. She said that she heard something about it being through war," and I was like, "Okay. I need to get involved."

So it became part of outreach for me as well, which is why it's so important that Bunim/Murray Productions got together with the Ford Foundation. They're continuing to help us with outreach and social engagement programs and educational programs because unfortunately, school shootings and shootings in our community and our neighborhoods are happening every day. Our children are witnessing, if not being the victims of, these horrible crimes, and no one is getting proper help. It may have changed now; I think that unfortunately, with the horrible circumstances of Newtown, it sounded like that community was doing a lot of outreach with the children of the parents, but it's happening far too often, and I wanted to show that. And I didn't want to just write off communities that maybe have lower socio-economic backgrounds than other communities; I felt that there was a real class issue about this particular school shooting, and the little help that they received was absolutely stunning to me.

Is there a call to action you hope viewers take away from the film?

People have come up to me and said, "What do you want us to do? I'm so angry!" And I've said, "Well, go volunteer! Go be a part of your community and go be a part of your neighborhood and find out if you're doing what you need to be doing to be an ally to the LGBT community. Get involved." There are so many straight people who feel that LGBT people are completely equal across the board in every way, and what they don't understand sometimes is that these horrible circumstances are happening to people in the LGBT community and that they can be a presence in a positive way and they can affect change just by being a part of the movement. That was a real hope and dream that I had for this film, that it would have an afterlife. I'm very proud of the work everyone did for this film, but the real reason I made it was to affect change, for awareness and acceptance. I think we need to go way beyond tolerance. Tolerance is not enough. Acceptance is really the only word that should be attached to anyone of difference.

Valentine Road premieres October 7 on HBO.

Katie Bieze received her MA in Film & Video from American University, and her BA in Literature with Certificates in Documentary Studies and Film/Video/Digital from Duke University. She currently works for Share Our Strength, a nonprofit organization working to end childhood hunger in the United States.

WESTDOC Bridges Creative and Business Sides of Doc-Making

This year's WESTDOC conference—which took place in mid-September at The Landmark Theaters in West Los Angeles—saw the best of both worlds for documentary filmmakers. Hosting conversations with prolific filmmakers such as Ondi Timoner and Rory Kennedy on one hand, while presenting panels with funding and digital distribution experts on the other, WESTDOC struck a perfect balance between the creative and business sides of documentary filmmaking.

The conference covered all the steps between these two sides—starting with fundraising, an essential component of the filmmaking process. The first topic of the day was crowdfunding.

Adam Chapnick, principal at the mega-successful crowdfunding site Indiegogo, explained how Indiegogo first started out as a platform to support and fund only film projects, because independent filmmakers were getting conned by distributors. "Documentary filmmakers were one of the first to get into crowdfunding," Chapnick maintained. In fact, he founded Distribber (purchased by Indiegogo in 2010), which was a flat-fee distribution service that placed independent films on VOD platforms while empowering filmmakers to keep 100 percent of their revenue.

The idea of crowdfunding is not new. Danny Kasiner, chief officer at Crowdjammer, explained how crowdfunding has always been around, but now with the Internet and crowdfunding websites, it's become easier than ever to reach your target audience to gain funds. He explained the importance of finding your audience first before getting ready to launch: "Even if your documentary has a very niche audience, doing a little research and connecting with your audience on Facebook and Twitter could make all the difference in your crowdfunding campaign." Kaisner should know: Crowdjammer works with any crowdfunding platform, and helps artists and companies use social media to build fans who pledge campaign support during a pre-launch phase. This takes the guesswork out of crowdfunding, leading to a higher success rate.

With crowdfunding being such a major source of funding for filmmakers now, the next step after funding and making an independent documentary would be distributing it. So what steps can one take to seek distribution, and how has theatrical distribution changed in the past few years?

It seems that everything is going digital. As opposed to the days when documentary filmmakers simply had to have a distributor to be able to release their film in theaters, theatrical distribution can now be achieved through online sources. Dan Parnes, content partnerships and communications director at Tugg, a site that gets films into markets based on audience demand, explains how this works: "If enough people in an area request a screening of a film on Tugg.com, a screening can be set up. We deal with exhibitors and take care of all the logistics. People then buy tickets to the screening online." With enough demand on Tugg, screenings can be set up in multiple cities over a period of time, thus getting independent films into theaters without a formal distributor.

And then we have KinoNation, a cloud-based site for content owners to distribute and exploit feature films across hundreds of on-demand platforms, in multiple territories and languages. Co-founder Roger Jackson comes from a documentary filmmaking background, having produced Darfur: Quest for the Human Spirit (2009), No Child is Born a Terrorist (2008) and Arsenic: The Largest Mass Poisoning in History (2005). Transitioning to the business side, Jackson stressed the importance of exclusivity. "When signing on with an online distributor, giving away exclusive streaming rights to your project is not recommended," he advised. KinoNation distributes films under its banner to Hulu, Netflix and other paid streaming platforms. With new distribution opportunities opening up, companies like Tugg and KinoNation make sure that independent documentarians with good content don't get left behind.

Straddling the artistic side and the business side, a keynote speech by two-time Sundance Film Festival Grand Jury Prize winner Ondi Timoner revealed not only the creative strategies behind her work, but also her expertise on digital distribution and crowdfunding. Timoner's recent Kickstarter campaign achieved 150 percent of her fundraising goal, making A TOTAL DISRUPTION the top documentary series event funded on that platform.

Other perspectives on both the filmmaking process and the business side of documentaries were offered by Academy Award-nominated filmmaker Lucy Walker; Lesley Chilcott, producer of the 2006 Academy Award-winning documentary An Inconvenient Truth; Melanie Miller, vice president of acquisitions and marketing at Gravitas Ventures; and Peter Goldwyn, senior vice president at Samuel Goldwyn Films.

This panel covered all the bases for documentary filmmakers, from distribution to the creative process. Goldwyn gave some good advice on clearances and paperwork. "You need a good lawyer," he said. "Don't use expensive music; get your clearances. If you have a good lawyer who knows about documentaries, they can do the legal and sell your documentary, and there are some really good sales agents out there as well."

Walker talked about new and interesting things that went into the filmmaking process for her new film The Crash Reel. "We have this shocking situation where kids are dying in action sports and nobody knows about it," she said. "We had to get grants to cover a lot of factors. It's not a money-making thing, but as far as the rewarding factor and the impact of the film, it's absolutely amazing."

Transitioning to the creative side of documentaries, a conversation with Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Rory Kennedy gave attendees the opportunity to learn the art of documentary filmmaking from one of the best in the business. But even successful documentarians had to start somewhere. "It was a learning curve, and I had no idea what I was doing," Kennedy admitted.

Kennedy has directed and produced more than 25 documentaries, but the beginning of her career wasn't easy. Kennedy talked about how she turned her passion on a subject into a proposal for a film, and then researched production companies who would want to partner with her. Gathering funds for her project was not easy either. "The fundraising process was difficult and took a long time," she said. But through her compelling storytelling skills and a strong will to emotionally connect with her subjects and their journeys, Kennedy was able to rise to the challenge.

WESTDOC concluded with PitchFest, a competition where one lucky project wins $7,500 for finishing funds. This year's winners, Kaitlyn Regehr and Nimisha Mukerji, won for their film Tempest Storm: Burlesque Queen. "We feel so grateful to have won this," said producer Regehr. "Especially because all the other projects were so amazing. We made incredible friends throughout this process and we felt privileged to be in such good company."

Mukerji, director of the winning project, added, "We had a great time at the conference and it was an amazing event to be a part of. We can't wait to go back next year!".

Minoti Vaishnav is Programs and Events Coordinator at IDA.

Reinvention at Independent Film Week: 'Hollow,' Media Center, Doc Pitching Among the Highlights

IFP's Independent Film Week, which ran September 15 through 19 in New York City, offered arguably its most diverse schedule in recent years. Blame it on the shifting landscape of independent film, or the increase in funding and distribution opportunities for documentaries—either way, the conference gave attendees the chance to fully understand how to stand out in an overcrowded marketplace. Held at the New York Public Library's Bruno Walter Auditorium at Lincoln Center, the annual conference was divided into five, day-long categories: "Future Forward"; "The Truth About Non-Fiction"; "Crafting a Career"; "#ArtistServices Workshop NYC Presented by Sundance Institute"; and "Re:Invent."

Leviathan co-director Lucien Castaing-Taylor delivered a keynote speech to close out Monday's slate of panels, which focused on hottest issues in the documentary genre. The panel "A Conversation with Documentary Subjects" included Cutie & The Boxer director Zachary Heinzerling and subject Ushio Shinohara, as well as American Promise directors/subjects Joe Brewster and Michèle Stephenson. A case study on Penny Lane's Our Nixon, released on television and in theaters last month by CNN Films and Cinedigm, was also part of the day's program.

Thursday's Re:Invent panels also focused on a wide range of documentary topics, including discussions about incorporating new technologies and alternative storytelling platforms into the genre.

The day kicked off with a conversation about the interactive documentary Hollow, which launched on June 20 and was featured on The New York Times Op-Docs site. The project was awarded a new media grant from Tribeca Film Institute.

Director/producer Elaine McMillion, co-producer/art director Jeff Soyk and technical director/senior developer Robert Hall discussed the community participatory project with Sarah Kramer, chief content officer at Imprint, who moderated the discussion.

Boston-based McMillion explained that she had originally planned to make a one-off about the future of McDowell County, a West Virginia-based rural community that is suffering from economic turmoil and population decay.

"I grew up close to McDowell County, but I'd never actually been there," McMillion said. "Everyone likes to paint McDowell as the poster child for all things bad, so when the [news media] talks about teen pregnancy and drug overdoses, they go to McDowell and put the locals' faces on [the screen]. Then everyone feels good about themselves because we aren't them. I really wanted to turn [that image] on its head. I was coming from a linear storytelling background, so I went there with the idea to make a film. But within several hours of being there and meeting all the different people, I knew it was not going to be a [single] film. It needed to include a lot of stories, data and participation from the community."

Since the 1950s, McDowell County has lost 80 percent of its population. According to the project's official website, "Demographers studying population in West Virginia estimate that the 10 communities that make up McDowell Count are just years away from extinction."

Using personal documentary video portraits, user-generated content, interactive data, photography, soundscapes and grassroots mapping on an HTML5 website, McMillion and her team designed Hollow to thoroughly document the struggles of community locals to save their county. In addition, numerous members of the community collaborated with the Hollow team on 20 of the 50 short documentaries featured on the project's site, in hopes of empowering the community to work together for a better future.

Soyk admitted that creating the comprehensive site was initially a struggle, due to geographical distance between members of the team. "We found some technology tools that helped us virtually be together, but I wouldn't recommend that," Soyk explained. "If you are going to create an interactive project with [multiple people], find space to get together."

Luckily for Soyk and fellow independent filmmakers, IFP's executive director, Joana Vicente, introduced a space for filmmakers to do just that—get together and collaborate. The Mayor's Office of Media and Entertainment and IFP recently partnered to create Made in New York Media Center, a 20,000- square-foot facility based in the DUMBO section of Brooklyn. The Center opens next month.

The panel that explained the Made in New York Media Center included Vicente, as well as Brent Hoff, the Center's director of programming; Nicholas Fortugno, chief creative officer at Playmatics; Brad Hargreaves, General Assembly co-founder; and Eugene Hernandez, director of digital strategy at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, who served as moderator.

Hoff, who had relocated to New York City from San Francisco for the job, explained that the new facility will be dedicated to assisting storytellers get their work done by offering co-working opportunities and continuing education, and by connecting artists to technologists, entrepreneurs and industry resources.

"It's a space for collaboration," Vicente added. "It's all about storytelling. Whether you are telling your story through an app, film, video, a game—you should become a member of the Center. What I think is really unique is not just the focus on storytelling and how we are bringing all of these [interesting people together], but we are also supplementing it with an educational program."

Facilities open to the public include an education center, featuring multiple classrooms designed to host an array of programs such as hands-on workshops, live demonstrations and expert seminars. Hoff said he hopes to bring a "writing room" class/seminar featuring various film and television writers at work.

Media Center members at various levels of participation can take advantage of an incubator space, designed to foster creation and collaboration between New York City's emerging storytellers, innovators and businesses; and community and co-working spaces, reserved for both individual day use on a first-come, first-served basis. The facilities also include conference rooms, editing rooms and a video lounge.

The Thursday lineup also included the "Art of the Documentary Pitch" panel. Industry executives fielding pitches included Cynthia Kane, senior producer of documentaries at Al Jazeera America; Kathryn Lo, director of program development for independent film at PBS and PBS Plus; and Nancy Abraham, HBO's senior vice president for documentary programming. After listening to each two-minute pitch, the panelists offered feedback while also providing some insight into the decision-making processes at their respective channels.

Kane advised each filmmaker after their 120-second pitch to "slow down, take a breath" and maintain eye contact with the panelists. "People are just inundated with information these days," Lo added. "I think if you get into the story without getting into the themes, you are going to be able to hook me."

Addie Morfoot writes about the entertainment industry for Daily Variety, The Wall Street Journal and Adweek. She has also written for The New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and Marie Claire. She holds an MFA in creative writing from The New School.

US District Court Rejects City of New York's Appeal on 'Central Park Five' Case

The United States District Court, Southern District of New York ruled on Wednesday, September 25, to quash the City of New York's appeal on their subpoena for footage from the filmmakers of the 2012 documentary The Central Park Five.

The appeal was the City's attempt to overturn the previous ruling in February denying the subpoena of outtakes from The Central Park Five. Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon produced the documentary, which examines the controversial and racially charged 1989 Central Park jogger rape case.

The court found that documentarians generally qualify as journalists with the benefits of Journalistic Privilege. In this case, the status of journalist was established in the face of arguments by City attorneys that Sarah Burns had learned of the case while working as a summer intern at a law firm. The City also argued that the filmmakers had lost the protection of Journalistic Privilege when they advocated on behalf of the subjects of their film.

When the Central Park Five team was first subpoened by the City of New York last October, they contacted IDA, given the organization's past efforts on behalf of filmmaker Joe Berlinger and his battles with Chevron over his footage from his 2009 film Crude. IDA, in turn, enlisted Los Angeles-based entertainment attorney—and longtime advocate for documentary filmmakers—Michael C. Donaldson. He, along with New York attorney Andrew Ciell, prepared and filed an amicus brief on behalf of the independent film community. The brief was in support of a motion filed by the filmmakers to quash the subpoena for their notes and outtakes. The documentary community, led by IDA,along with NAMAC, Film Independent and many independent filmmakers, lent their names to the amicus brief to support the cause.

"Documentary filmmakers gather and disseminate information about significant social and political issues," said Donaldson in a statement. "Through their films, they uncover new information, advocate action and initiate public debate where none had previously existed. Preservation of Journalistic Privilege for documentary filmmakers, in spite of how they initially find out about a story and in spite of how passionately they advocate for their subjects, is essential to documentarians being able to work effectively." The ruling in this case supports this right.

This case was the dominant subject of a lively Doc U this past January that featured Donaldson and Sarah Burns, as well as filmmaker David France, as they discussed the intersections of documentary making and journalism. For more on Doc U: The Doc Reporter, click here.

Defusing the Debate: 'After Tiller' Profiles Third-Trimester Abortion Providers

When we think of hazardous professions, that of an OB/GYN does not necessarily come to mind. But when such doctors perform late abortions, they perilously become the targets of an aggressive faction of the anti-abortion movement. In May 2009, Dr. George Tiller was gunned down while attending Sunday services at his church in Wichita, Kansas. Shockingly, he was the eighth such fatality since the passing of Roe v. Wade in 1973. With his death, there are now only four doctors in the country who openly provide third-trimester abortions.

These doctors are vilified, hunted, harassed and persecuted constantly by an increasingly sectarian pro-life movement. But to their patients, they are caring, compassionate listeners who assist them at a very vulnerable stage in their life. After Tiller, a documentary by Martha Shane and Lana Wilson, delves into the lives of these four seemingly "controversial" doctors, who were close friends of Tiller, as they face numerous obstacles—from increasingly restrictive legislation affecting their medical practice, to personal and moral dilemmas.

Documentary spoke to Wilson and Shane, on the phone from New York. Wilson explained the origin of the film: "The idea came from watching the news and thinking about how Dr. Tiller was killed in a church. Since many of the anti-abortion people are Christians, isn't it surprising that their number one villain is a Christian himself, who had been going to the same church with his family for over 25 years? And [I also thought], Who would do this kind of work? What are their lives like? What is it like to have all this pressure on you every day, going to your job, driving in an armored car? Dr. Tiller was shot in the 1990s, and went back to work the next day. What kind of personality would it take to do that?"

From the outset, the filmmakers were clear that they did not have a political agenda, but rather, a humanist goal: to give the four doctors a voice. "We wanted to shed light rather than heat over the issue," Wilson explains. "There were just so many questions that remained from hearing the story of Dr. Tiller's death that weren't really addressed in the news coverage. It was treating it in the same ideological terms that they always treat the abortion issue—a black-and-white debate, and [the] two camps on either side are very polarized. They weren't looking at the doctors or the patients involved as complex human beings."

What transpires is an intimate portrait of four exemplary physicians who soldier on in their profession despite increasing hostility, legal and logistical issues (such as having to open a new clinic out of state once late abortions are outlawed in their jurisdiction), and difficult personal choices—the wish to retire and not continue to expose their family to danger.

Late, or third-trimester, abortions (after 25 weeks), make up less than 1% of the total abortions in the US. A widespread misconception is that the women who request such abortions do so brazenly and carelessly, because they were too negligent to end their pregnancy earlier. But in fact, the truth could not be more different; the overwhelming majority of late abortions are sought for the most devastating medical reason: a fetal abnormality detected late in the pregnancy.

Many intimate vérité scenes of the film reveal the intense suffering of incredibly distraught patients, for whom this was a planned pregnancy. These unquestionably loving, caring and often deeply religious parents—who until recently were joyously expecting a healthy baby—are now in a desperate situation and racked with guilt by their decision.

As Martha Shane points out, "Audiences don't have any idea the percentage of these abortions that are wanted pregnancies. It's really a child to them already; they have been preparing for it. The patients give you a really good sense of how much they love this child already, even though it hasn't been born."

It is difficult to view such scenes and maintain a dry eye. Since a late abortion effectively entails the delivery of a stillborn, the mothers are saying hello and goodbye to their child at the same time, and the doctors and staff do their best-despite the tragic circumstances—to make this a precious experience for the parents, complying with requests to spend time with the fetus, for hand and footprints, and creating a memory box.

Obtaining patient participation in the film was quite an obstacle. "Initially we wanted to do portraits of the doctors," Shane explains, "but pretty quickly we realized that what motivates them to do the work are these patients and how they really are the most desperate. And we realized we needed to have patients in the film—at least their voices—in order to really have a full portrait of these doctors' lives. The most difficult part of making this film was not knowing necessarily if we would be able to find patients who were willing to be in the film."

Wilson adds, "Understandably, these people are going through some of the most challenging situations of their lives and the vast majority of the people did not want to participate in the film. So there was a lot of waiting around, hoping a patient would agree. We had the counselors bring it up in the initial session...Most people don't understand why you might seek a third-trimester abortion because the circumstances are unimaginable...The few patients that participated in the film got the value that this would bring to increasing compassion and understanding among a wider audience."

Throughout the filming at the clinics over the course of two years, the youthful filmmakers were often asked if this was a part of a school project. Indeed, Wilson and Shane feel that in addition to hiring female cinematographers (Hillary Spera and Emily Topper), their youth made them more approachable, particularly when the patients were facing the situation alone: "Martha and I, being 27-year-old women, helped too, because not only we were an unintimidating presence, but also we were the same age as a lot of the women who were there; we were women of a child-bearing age. Some women were there alone, and one said, 'It was so nice I had a couple of other friends around as I went through this.'"

The controversial subject matter made funding even more difficult than a typical documentary. Major documentary grant foundations were extremely wary and fearful of being involved with such a sensitive issue, and were concerned of the political repercussions of the film. "We would say that we are just going to take a very honest nuanced look at this," Wilson recalls. "And I think people understood that when they saw the final film."

Luckily, supporters like the Sundance Documentary Fund and Chicken & Egg Pictures understood their vision early on. "Chicken & Egg were great," Shane says. "They were one of our earliest supporters. They are a documentary fund; they fund films specifically by female directors, and social issue films. And they provide not just financial support but also a lot of mentoring. They helped us a lot on how to pitch the film to funders." The film also received support from IDA's Pare Lorentz Documentary Fund.

Given Dr. Tiller's murder and past attempts against the doctors, the filmmakers were justifiably concerned about the safety of their subjects and did not wish to expose them to even greater danger. Shane states, "From the very beginning we had conversations with them about security and they all came to the conclusion, on their own, that without telling their story there's sort of a vacuum and there's silence; it's so easy to vilify them in that situation. I feel that what our film does is humanize them and make them more relatable to people regardless of how you feel about the issue of abortion. We were careful not to show where they live and what car they drive, but for the most part we found that the anti-abortion people already know most of this information."

Security concerns were even extended to the festivals: At Sundance, where the film premiered, there were armed guards, metal detectors and bag checks at each screening. But in fact, reactions to the film were overwhelmingly positive. "We went to Sundance and we were concerned that there might be hostility; we were prepared for protests," Shane maintains. "And we were very grateful to the festival that they wanted to take all the precautions necessary. There is a history of violence in this country against abortion providers and clinics, and we wanted to make sure that the doctors and the audience members would feel comfortable. I hope that people were comforted by the fact that we were paying attention to security. The best part for us was seeing the doctors get all this positive attention and having people say how much they admire them and how grateful they are for the work they are doing. It was wonderful for us to see that. What they are more used to seeing are threats and harassment and more negative attention; with the film, they were getting more of the positive attention that they deserve."

Whatever one's personal views about abortion, After Tiller is a thought-provoking, challenging and sincere film that shatters preconceptions and provides novel perspective on a timeworn debate. It reveals four doctors who are acutely aware of the ethical and moral complexities they have to navigate on a daily basis.

"There are also people who come in and don't change their mind, and feel just as strongly as before," Wilson observes. "But they always tell us that they felt it was fair, and that they were glad they saw it because they learned some things they did not know before. If people are thinking and talking about this issue in a calmer, less attack-oriented way, and it raises questions they had not thought about before, then that's a success for us."

After Tiller opens September 20 in New York, and October 4 in Los Angeles. The film is distributed by Oscilloscope Laboratories.

Darianna Cardilli is a Los Angeles-based documentary filmmaker and editor. She can be reached at www.darianna.com.

Meet Ken Jacobson, IDA's New Education Director

By Tom White

Ken Jacobson recently came on board as IDA's director of educational programs and strategic partnerships—a new position created to accommodate a critical pillar of IDA's core mission: education. Ken comes to us from the Palm Springs International Film Festival and ShortFest, where he served as education/outreach coordinator and programmer. Over the years he has taught both film and video production and cinematic history, at every level from high school thought continuing education, and has made documentaries as well. He is a graduate of Stanford University's prestigious Documentary Film and Video Program.

Ken Jacobson recently came on board as IDA's director of educational programs and strategic partnerships—a new position created to accommodate a critical pillar of IDA's core mission: education. Ken comes to us from the Palm Springs International Film Festival and ShortFest, where he served as education/outreach coordinator and programmer. Over the years he has taught both film and video production and cinematic history, at every level from high school thought continuing education, and has made documentaries as well. He is a graduate of Stanford University's prestigious Documentary Film and Video Program.

Two weeks into his new job at IDA, we interviewed Ken by e-mail, and he shared his thoughts on teaching, program development, Los Angeles and the docs that have inspired him the most.

Documentary: You graduated from Stanford's master's program in Documentary Film and Video, and your work experience since then has been primarily in education and programming. Talk about how you chose and followed this career path.

Ken Jacobson: The long and somewhat winding road to where I sit today began with my desire to be a documentary filmmaker. But even when I was at Stanford, I was designing and teaching a class to undergrads on documentary production and creating a workshop for youth in East Palo Alto. So, the desire to teach was always there. And it also runs in the family: Both my dad and my sister have been full-time teachers. So, when my frustration over the inability to crack the code of being a self-sustaining documentary filmmaker reached a certain threshold and the opportunity presented itself to start over and begin a teaching career, that's the path I took. I always had in the back of my mind that I would return to the documentary world down the road, so the job at IDA in a way represents a convergence of these two paths—the documentary path and the educational one.

D: You've taught at a variety of educational levels: high school; university, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels; and adult/continuing education. What have been the most rewarding aspects of your teaching career thus far?

KJ: It may be a cliché, but it's true that teaching and producing programs for young people has provided me with the most satisfying moments of my career. As a high school video teacher, the highlights were giving students the tools and providing the support for them to create projects that, starting out, they weren't sure they were capable of. Just recently, I happened to cross paths again with one of the high school students I taught, who happened to have a film in the Palm Springs ShortFest. It was inspiring to see how that student had transformed into the accomplished filmmaker that he is today. Similarly, as part of my educational outreach work at the Palm Springs International Film Festival, nothing beat the thrill of seeing the response to our annual Student Screening Day, when the filmmakers and subjects of films such as Louder Than a Bomb and Shakespeare High came on stage and the students in the audience erupted with applause. Nothing has shown me the power of documentary more than that.

D: Over the last five years, you've worked with the Palm Springs International Film Festival and ShortFest as education/outreach coordinator and documentary programmer. You also launched and implemented a year-round educational and community program. Talk about the process of setting up this program-the partnerships you created in the Palm Springs community and school districts, and the challenges of creating a year-round infrastructure for an organizational model—a festival—that's perceived by some as a once-or-twice-a-year event.

KJ: Setting up year-round programs, like we did in Palm Springs, is pretty much the same with nonprofits everywhere. First, you need leadership within your organization—you have to want to get to where you're going and have a somewhat clear vision of what you want things to look like. Second, you need to work incrementally. When you are operating as a nonprofit, with a board, you need to show them results, and those results generally happen brick-by-brick, program-by-program, event-by-event. Third, you need to find good partners who themselves provide strong programs for their constituents, whether they be library patrons, in the case of our Behind the Scenes Filmmaker Series at the Rancho Mirage Public Library, or students, in the case of the Palm Springs Unified School District. Next, you need to be lucky enough to work with people in those organizations with whom you can build long-term trusting relationships. Finally, you need to be able to get "butts in the seats"—you need programs that attract enthusiastic participants. There, that's my formula for success!

D: You are IDA's first ever full-time education director—your title is Director of Educational Programs and Strategic Partnerships. I know this is early in your tenure, but can you give us an idea of some of the programs you would like to explore with IDA?

KJ: Doc U is the centerpiece of IDA's educational and professional development programs, and I will be working with our executive director, Michael Lumpkin, and programs and events manager, Amy Jelenko, and the rest of our staff and board, to see to it that the programs continue to be of the highest quality and greatest benefit to filmmakers. Right now, we are looking to expand the program to become an intensive series of daylong workshops throughout the year that would be held here in LA at our new offices in Koreatown. I will also be exploring the viability of creating an online presence with Doc U-type experiences available through our website. Creating mentorships is another goal; we need to do all we can to support our members and fiscal-sponsored projects with professional development opportunities that can reach them, whether they are in LA or halfway around the globe.

D: For the "Strategic Partnerships" side of your title, what kind of organizations would be optimal for IDA to form alliances with?

KJ: We are looking for organizations that share our mission, are committed to serving documentary filmmakers in all capacities, and enhance the documentary community. Currently, I have the privilege of working with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the Dolby Institute on a sound and music panel that we will be presenting at the Academy's Linwood Dunn Theater on Oct. 5. I'm also working closely with the Black Association of Documentary Filmmakers-West (BADWest) on a panel coming up on October 21. These are just some of the partnerships that I am excited about. Stay tuned for more!

D: Although California has been your home for your entire career, you are new to Los Angeles. What do you appreciate most about this city? What are the key strengths of the documentary community here?

KJ: It's too early for me to say what I appreciate about LA. I don't think I'll be satisfied until I discover the city's best coffee and bakeries...And three days after moving here, my car was rear-ended, so I'm not sure that the city fully appreciates me yet, either! As far as the documentary community goes—and my Bay Area comrades might cringe if they read this—I feel that it is right up there among the strongest anywhere in the US—or the world. The quality of the work, the passion for the medium and the willingness to contribute to a larger community are really amazing. And the organizational support in LA, with IDA, AMPAS, Film Independent, Sundance and top educational institutions here, is probably second-to-none.

D: Finally, given your rich experience in studying, teaching, programming and making documentaries, what are some of the docs and docmakers that have truly inspired you?

KJ: The two docs that I keep coming back to that are the most personally significant are The Times of Harvey Milk and the TV doc series Eyes on the Prize. The Times of Harvey Milk as a powerful, feature-length dramatic documentary experience stands alone for me. Aside from the filmmaking, which is of the highest quality, I can't deny that as a native San Franciscan, it is, for me, a poignantly local story that is also universal and of great historical significance; I just feel the film in my bones. Similarly, the first Eyes on the Prize series had a profound effect on me and really changed the course of my life. When I moved to Boston in 1986, the first thing I did was contact Blackside Productions to beg them to be an intern. The timing wasn't right at first but later, when they cranked up the second series, I did get in the door and had an amazing experience as an intern there. From that experience, I knew that documentary life was it for me.

Restoration and Reflection: The 2013 Re-releases of 'Le Joli Mai' and 'Far from Vietnam'

What does the present have to say to the future? What will that future say of the past? These are questions films and filmmakers ask in relation to their work. When these works are restored and re-released for a current generation, we may also ask, Why these films, and why now? We assume there is a significance.

Two important films from Chris Marker's body of work are being re-released in North America through Icarus Films, having gone through rigorous restoration processes. Both Le Joli Mai (1963), restored by the film's cinematographer and co-director, Pierre Lhomme, and Far from Vietnam (1967), restored by the Archives françaises du film du CNC , were official selections of the New York Film Festival and Cannes. Fifty years ago, the difference of four years between the two films may have seemed a substantial separation, with neither film directly acknowledging the other. Today, however, the brief span between them creates a dialogue that speaks to the cultural resonance of the events of Paris in May 1968—felt today, for example, in the Occupy movement, the Arab Spring and the ongoing discussion over potential Western military intervention in Syria.

In March 1962, France signed the Evian Accord, giving Algeria its independence, and signaling a shift in decolonization conflicts subsequent to the end of the Second World War. Marker and Lhomme's Le Joli Mai (The Lovely Month of May) is a portrait of Paris, set in May 1962, during the country's first springtime peace in 23 years. The film, divided into two parts, "A Prayer From the Eiffel Tower" and "The Return of the Fantomas," is equally an investigation into the personal lives of its citizens and the political and social life of the city. The city—and the country—are not without conflict; conflicts have become internalized within the individual inhabitants and collective civic consciousness of Paris. An ebbing, transient and transitioning tension remains. The suggestion in Le Joli Mai is that Parisians, given the recent peace, are now free to reflect on their own lives and the life of their city. As in Far from Vietnam, we get a sense of how conflict impacts those domestic and abroad.

In stark contrast, though, Far from Vietnam's conflict seethes at the surface, in content and intention. The project, initiated and edited by Marker into a collection of fiction and nonfiction films by Jean-Luc Godard, Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Agnés Varda and Alain Resnais, is an explicit protest against the United States' military involvement in the Vietnam War. Where Le Joli Mai explores a greater social whole through the perspective of the individual, Far from Vietnam dissolves the individual's perspective and rationale into abstracted factions, reducing individual citizens to the sides they take and the banners or batons they wield. The apparent, perhaps superficial, tranquility of Le Joli Mai is in juxtaposition to Far from Vietnam's internal and external violence, a violence that is visibly manifested in the clashes between protestors and supporters, but also, it seems, conspicuously steeped in the very heart of Americans. Together the films act as bookends; what is not seen, but easily inferred, are the intervening years, between 1962 and 1967, when subtle stirring segues into explosive release, eventually culminating in events in France and the United States with, respectively, the May 1968 General Strike and the May 1970 Kent State shootings by the Ohio National Guard of students protesting President Nixon's Cambodian campaign.

The subjects in Le Joli Mai discuss what makes them happy, what their hopes are, what they face each day; their quotidian rituals fall somewhere between the sacred and profane. A man who sells suits describes the pleasantness of his drive home, if there is not too much traffic. Female prisoners itemize facets of their internment. A young couple detail their wedding plans. We watch a wedding reception. A priest speaks of unions. One subject states, "If everyone went on strike, the government would have to buckle." As it turns out, precisely six years later the students and workers would do just that-but as we also know, the government did not buckle. What is intriguing about Le Joli Mai are the premonitions it provides; there are several instances-not the least being archival news footage of the February 1962 Charonne Metro Station Massacre and the demonstrations in response (the only footage not shot by Pierre Lhomme)—where Parisian discontent becomes visible. Looking ahead to May '68 or even Godard's films from1967 onward, the insinuation is that these minor turbulences were laying the groundwork for a larger, ostensibly imminent collision.

As history has further evidenced, massive paradigm shifts take their first steps by placing an initial toehold at small scale: first, a neighborhood; then, progressively, a city, a country, a continent and beyond. Paris in May 1962 looks, in many respects, the way it will a year later, and several years later. Paris in 1968 may have looked not altogether dissimilar to Berlin in the late '80s, leading up to the fall of the Wall. More recently, Istanbul, Cairo, Tehran and Tripoli have demonstrated the effect of elevating scales of internal conflict, as the events poured over nationwide, resulting in undermined or removed governments and international recognition and support. It would have made for an interesting historical exercise to have captured, as Marker and Lhomme did, the conversations the citizens of these cities were having in the years leading up to their revolutions.

But this makes the Vietnam War protests in the United States an anomaly. Decades later, it is questionable how much these protests, intrinsically and fundamentally, altered the sociopolitical landscape. The United States government continued the conflict, which carried over to Cambodia. They set an interventionist hawk agenda within their foreign policy. Afghanistan, to many, was justifiable and Iraq, while widely unpopular, has not carried the same cultural, generation-defining gravity as Vietnam. It begs several questions, one being the same question every successive generation asks: Have we not learned from our mistakes?

Far from Vietnam, however, may provide an answer—or at least insight. Protest divided a nation, pitting its citizens against each other, which, although unpleasant, could also be passionate, bringing to life a population lulled by the prosperity that came with the end of World War Two, a sleepwalk characterized by proliferating, consumer-driven homogeneity, the suburbs, television and its advertisements. If quiet, critical and evolving dissent is inherent in the nature of Parisians, than perhaps physical altercation is necessary to the psychological equilibrium of Americans. This implies that conflict itself—not the outcome—is the point. And this is precisely what Far from Vietnam so graphically depicts. It is arguably shocking less because of the intensity of aggression between supporters and protestors, than because we know this exact dynamic continues to the present day, despite being faced with the horrors and atrocities committed on nameless, unidentifiable "others" on the opposite side of the world.

Arguably, it is quite ironic for the French to be making films in reaction to what is essentially another form of colonization, by the United States, of a former French colony. Political positions are, over time, revealed to be mercurial and often forgotten, if not forgiven, then placed within a sympathetic context. The objective is not to fix the polarity, but to simply be an observer or marker of time. As the Note of Intention to Le Joli Mai states:

"There is one question the writers wanted to ask themselves. In 25 or 30 years, what will those who allude to the 1960s have retained?

"What will we fish out from our own years? Maybe something completely different from what we see as being most forward thinking now, the film Le Joli Mai would like to offer itself up as a petri dish for the future's fishers of the past. It will be up to them to sort out what truly made its mark and what was merely flotsam."

The re-release of both Le Joli Mai and Far from Vietnam may be seen as an attempt to answer this question. Or, as a return to the conversation, the "wrinkles" intentionally left in the images through restoration, adding nuance and inflection to the cinematic voice.

The restored version of Le Joli Mai opens theatrically at New York's Film Forum on September 13, then tours to Los Angeles, Chicago, Seattle, Houston and other select cities. Far from Vietnam, which premiered August 28 at New York's Lincoln Center, screens next at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston from September 25 through October 3.

Justin Ridgeway is a Toronto-based writer and art consultant.

The Locarno International Film Festival combines a spectacular lakeside setting in Switzerland, near the Italian border, and an easy-going resort vibe with an eclectic program of provocative films. The third oldest festival in Europe—this year was its 66th edition—and better known there than in the US, Locarno has a diverse mix of innovative and traditional film that draws locals, international film enthusiasts and industry pros. The city takes it all in good spirits: Shop windows, trash cans and rentable bicycles flash the leopard spots of the festival's symbol, and residents turn out in force for the popular open-air screenings in the Piazza Grande.

Although the Swiss festival offers crowd-pleasers and retrospectives of popular cineastes, programming during Carlo Chatrian's first year as artistic director reaffirms the festival's dedication to discoveries and cutting-edge work. That's also true for nonfiction films, which appear in virtually all festival sections.

Pays Barbare, by longtime filmmaking partners Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi, illustrates that commitment to films that stretch the medium. The directors' work repurposes archival materials with the express aim of commenting on the present through the past. Here, they assemble and manipulate negatives, photograms and other materials collected by private individuals during the Italian colonization of Libya and Ethiopia. Juxtaposing images of eroticized Africans, military displays, Europeans at play and at official gatherings, the filmmakers invite us to think about the way perceived ideas of exoticism, primitivism and barbarism permit and perpetrate atrocities.

Art intersects ethnography in the rigorously structural Manakamana, the first long-form doc by Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez. For the approximately ten-minute length of a 16mm reel, a stationary camera records the occupants of a cable car carrying pilgrims to and from the Manakamana temple in Nepal. Eleven times, the car empties in the dark station and new occupants take their places. Silent, talkative, young, old, men, women (and goats!), some play to the camera, others try to ignore it. With no camera moves or edits to direct the eye, viewers create their own compositions and narratives and ultimately confront their own act of observing. Manakamana took home first prize in the Filmmakers of the Present competition.

Locarno's centerpiece venue is the Piazza Grande, where audience-friendly films screen each night to around 8,000 viewers. A documentary about the polarizing far-right Swiss politician and banker Christoph Blocher doesn't seem like a natural for this venue, but Jean-Stéphane Bron's L'Expérience Blocher filled most of the seats, no doubt a result of the profound effect Blocher has had on Swiss politics and economics. (He worked to keep Switzerland out of the European Union and he is fiercely anti-immigration.) Much of the documentary consists of interviews conducted in the subject's car, with Bron adding his own leftist perspective in voiceover. Not being a local, I had difficulty understanding the intricacies of Blocher's career, which may have contributed to my feeling that Bron never really penetrated the image Blocher cannily manages.

One of Locarno's major documentary showcases, the Semaine de la critique, features a week of international or world premiers selected by members of the Swiss Association of Film Journalists and Critics. Watermarks—Three Letters from China, by Luc Schaedler, takes an anthropological approach to economic realities in three regions of China. In the drought-stricken north, young people driven from the farm by harsh conditions must find work in factories or in the coal mines. Jiuxiancun in the lush, rainy south, while economically stronger, is still dealing with the after effects of the cultural revolution, trying to balance the dictates of the new China with the collectivism of the past. A 19-year-old woman in metropolitan Chongqing, where capitalism is taking hold, leaves behind her adopted family's fishing life on the polluted Yangtze to work in a restaurant. Their candid, thoughtful and often emotional words reveal individuals caught between reality and their hopes for the future.

Globalization dramatically affects developing countries with natural resources ripe for exploitation. Rachel Boynton's well-researched and even-handed Big Men follows the ongoing development of Ghana's oil industry, comparing it to the disastrous state of affairs in Nigeria. The slickest of the selections that I saw, the doc profited from Boynton's excellent access to oil executives, Ghanaian officials and Nigerian activists who are presented with all their contradictions.

Winner of a social-ethical prize, Flowers from the Mount of Olives, Heilika Pikkov's first feature, profiles an 85-year-old Estonian nun, whose unusual path to a Russian Orthodox convent in Jerusalem took her through three marriages, drug addiction, translating for the Nazis, and a long career in cancer research. Although the director's observational style was frustrating at times, leaving me with unanswered questions, Pikkov achieved a remarkable intimacy with her subject.

Five short docs made up Focus Syria, one of several sections centered on a specific region. Two of the five depict conditions in Syria prior to the revolution. Black Stone (2006), by Nidal Al-Dibs, chronicles the lives of four children in a poverty-stricken area just outside Damascus, who help support their families by collecting and selling scrap metal. Reem Ali's Zabad (2008) poignantly observes a Syrian family considering emigration for political reasons but distressed at leaving behind the wife's schizophrenic brother. Both films were banned in Syria.

Randa Maddah's ravishing Light Horizon, filmed in a Syrian village on the Golan Heights bombed by Israeli forces in 1967, wordlessly evokes, in one seven-and-a-half minute shot, the human need to recapture home space after devastating destruction. True Stories of Love, Life, Death and Sometimes Revolution, by Nidal Hassan and Lilibeth Rasmussen, was originally meant to examine the situation of women in Syria, but when anti-government protests broke out the day shooting was to begin, the filmmakers' focus inevitably changed. They traveled the country recording demonstrations, artists, activists and ordinary people as well as their own difficulties while filming. The resulting rough-edged collage reflects the torn emotions and chaos of the early days of the revolution.

During the post-screening discussion with Hassan, Maddah and Hisham Al-Zouki, moderated by programmer Lorenzo Esposito and Paris-based Syrian director Hala Alabdalla, the filmmakers talked about the difficulties they face in bringing Syrian narratives to the outside world. Al-Zouki, whose film Untold Stories follows the developing activism of a young woman traveling from Damascus to her home town, made his film to acknowledge the often overlooked role of women in the revolution, but also to show the reality on the ground to a public that generally knows only accounts shaped by the news media. A regime threatened by the power of images has terrorized, jailed and sometimes executed filmmakers and other artists in the opposition. Al-Zouki, who had been previously jailed for seven years, currently lives in Norway. Hassan was detained for several months. Reem Ali escaped to Lebanon and is without a passport. Asked how they can continue to work under these conditions, Hassan admitted that they themselves don't know how to go forward.

Other short and medium-length docs screened in the Pardi di Domani competition for filmmakers who have not yet made a feature film. Christina Picchi's Zima, a lyrical 12-minute portrait of winter in northern Siberia, and one of only two docs in the international competition, won second prize.

Locarno screens such a rich array of nonfiction films that it wasn't possible to see all or even most of them. Among those I missed were the final four installments of Werner Herzog's Death Row series (Herzog was also feted with the Pardo d'onore Swisscom, a career achievement award.); Joaquim Pinto's E Agora? Lembra Me, winner of a special jury prize; Luis Patiño's Costa da Morte; and Thom Anderson's Red Hollywood.

Torene Svitl is a Los Angeles-based consultant and writer.

From Jacob Kornbluth's Inequality For All

The economy. The mere mention of that word makes some eyes glaze over and ears tune out. It's an umbrella term that conjures up images of stock-price displays, bells ringing at the New York Stock Exchange, houses in foreclosure, fat cats on Wall Street, and self-proclaimed experts spouting unintelligible lexicon on CNBC.

So one would assume that a film about the economy would be dry, arcane and rather unentertaining. But Inequality for All, winner of a Special Jury Prize in Documentary Filmmaking at this year's Sundance Film Festival, proves quite the contrary. Jacob Kornbluth's first foray into nonfiction film is engaging, amusing, colorful and, most importantly, digestible.

The film focuses on the country's widening wealth gap in the past 40 years: The richest 400 Americans control more wealth than the bottom 150 million Americans; the six WalMart heirs, more than the bottom 33 million families combined. At present, the United States ranks 64th in income inequality, placing lower than the Ivory Coast and Cameroon. When it comes to distribution of income, why is the US sandwiched among third world countries instead of its G7 counterparts?

Enter Robert Reich—congenial professor, best-selling author and Secretary of Labor under President Bill Clinton. He explains in layman's terms why this has happened and why such inequality is bad for the economy and for the social fabric of the country. We follow the diminutive Reich, who amply makes up in personality and charisma what he lacks in stature, as he teaches his Wealth and Poverty class at University of California, Berkeley (now the largest undergraduate class there, totaling 805 students last spring) and zips around—in an aptly proportioned Mini Cooper—to union rallies.

Kornbluth, speaking by phone from New York, explains, "Reich has the unique ability to break down complex ideas in a way people can relate to and understand. His stature makes him who he is as a person; it makes him a very compelling character for a documentary. He's a fascinating person; he's very likeable on camera. It also helps that I know him very well."

As to how that relationship came about, Kornbluth recounts, "I met him in 2008. I was trying to make a fiction film called Love & Taxes. I was shooting a test scene, and we needed someone to play a former IRS commissioner in a comic way. I asked [Reich] if he would do it, and he came out and did. I don't know if the scene worked, but we met each other and stayed in touch. And we were friends reasonably quickly."

When asked about the genesis of the film, the director explains that it was fairly organic: "I was increasingly worried with what was happening with the economy and my friends who were struggling to make it—even those who came from solid, middle-class backgrounds. And 2008 brought that to a head for me. I felt like I was a little bit trapped in the 24-hour news cycle, and I wasn't really getting the information [in a way] that was explaining things to me. I met Robert Reich and I asked him simple questions about the economy that I wanted answered. And we started making short, two-to-three-minute videos that I would post on my Facebook page. And thousands of people started watching these videos, so I had a sense that people were hungry for that type of information. I had a sense that my questions were everybody's questions."

Using colorful graphics that match Reich's persona, the film delivers a multitude of depressing facts and statistics: The median income of a male worker today ($39,000) is lower than it was in 1968; stagnating wages coupled with rapidly rising costs in childcare, education and health care have led to the erosion of middle class income; conversely, executive compensation has skyrocketed, with the average CEO being paid 350 times more than an average worker at the same company. According to the US Department of Labor, the median pay in 2012 for CEOs was $9.7 million. The bell curve of income distribution has shifted increasingly to the left, leaving a vast underclass of nouveau pauvres

But why is that bad for the economy? Because, as Reich explains in the film, the middle class is the engine that drives consumer spending. By undermining the purchasing power of the middle class, we are trapped in a vicious circle of dwindling consumption and slower economic growth. "When middle class consumers have to tighten their belts, the whole economy suffers," he says. It's not a zero-sum game.

Even though the last few decades have clearly shown that Reagan-era "trickle down" economics does not work, the director takes great care in not vilifying the rich. Kornbluth sought to include the 1 percent in his film. He finds an enlightened spokesman for that elite: pillow manufacturer Nick Hanauer—CEO, venture capitalist and early investor in Amazon. As Kornbluth notes, "We needed the perspective from the 1 percent, and the more I thought about it, the more I didn't want it to be a villain. I wanted a person who would share the view that the decline for the middle class is bad for the American economy. The movie is called, after all, Inequality for All. It's bad for the rich, the poor and the middle class."

Speaking by phone from Northern California, Reich adds, "The wealth gap is now a chasm...[but] there are no real villains. It's really a system that has failed to change and adapt. But unfortunately, it's harder to tell a convincing political story without there being any villains. And large numbers of people are angry, frustrated and scared because their paychecks are shrinking and they don't have jobs. They want villains."

The documentary is not all figures, graphs and data; in fact, there are some very emotional counterpoints, particularly when the film delves into the personal struggles of some middle-class families. Even more resonant is the personal explanation, close to the end of the film, as to what drives Reich to fight against bullies and defend the weak.

Kornbluth finds the frequent comparisons to Davis Guggenheim's 2006 film, An Inconvenient Truth, very flattering, adding, "It was a landmark documentary and it was very important film. The fact that that film was successful did help people to see that there was a way that this film could be made. They took what could be perceived as a dry topic and made an entertaining film that could be accessible to audiences."

With regard to his apprehensions about venturing in the field of documentaries for the first time, Kornbluth concedes, "I had a lot of concerns. One of them was: How do you make a film about such a heady topic as the economy? What does that look like? We didn't know how the film was going to look like going in; that's part of making a documentary. And I didn't know how this was going to turn out. For a fictional filmmaker, that was terrifying."

Whether his move from narrative into documentary films is permanent, Kornbluth admits, "There's such uncertainty going out every day, not knowing what you are going to shoot. It's scary, but it's also completely invigorating. In fiction filmmaking, I spend my entire time trying to get something truthful, something that feels authentic, and in docs, that's all you are dealing with. I just loved that. I'm hooked. I'd love to work on another."

As for Reich's biggest revelation upon seeing the completed film, his response was very telling: "The big surprise was to see myself over the last 30 years saying much the same thing. The younger version of me on TV and radio warning of the direction that we are going in terms of widening inequality and executive salary and so forth. And yet 30 years later, we are worse than when I began all of this. When I saw that younger version of myself juxtaposed against who I am now, making all of the same arguments, and warning what would happen...it shocked me. I've been talking about this for so long and to have the situation become steadily worse makes me wonder whether all the books, all the writing and all the work I've tried to do had any effect whatsoever."

But perhaps the movie will change that. Reich concludes, "My son Sam, when he saw the movie, said to me, 'Now Dad, for the first time I understand what you've been trying to say all these years.' I thought that was a hopeful sign."

Inequality for All premieres in theaters September 27 through RADiUS-TWC, and opens the IDA Documentary Screening Series on September 26.

Darianna Cardilli is a Los Angeles-based documentary filmmaker and editor. She can be reached at www.darianna.com.